Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein[a] (22 January [O.S. 10 January] 1898 – 11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, screenwriter, film editor and film theorist. He was a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage.[1] He is noted in particular for his silent films Strike (1925), Battleship Potemkin (1925) and October (1928), as well as the historical epics Alexander Nevsky (1938) and Ivan the Terrible (1945/1958). In its 2012 decennial poll, the magazine Sight & Sound named his Battleship Potemkin the 11th-greatest film of all time.[2]

Sergei Eisenstein | |

|---|---|

| Сергей Эйзенштейн | |

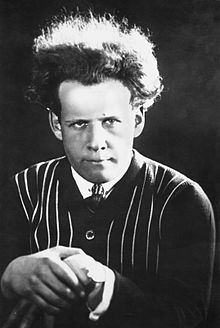

Eisenstein c. 1920s | |

| Born | Sergei Mikhailovich Eizenshtein 22 January [O.S. 10 January] 1898 Riga, Governorate of Livonia, Russian Empire (now Latvia) |

| Died | 11 February 1948 (aged 50) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Resting place | Novodevichy Cemetery, Moscow |

| Occupations | |

| Years active | 1923–1946 |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse |

Pera Atasheva (m. 1934) |

| Awards | Stalin Prize (1941, 1946) |

Early life

editSergei Eisenstein was born on 22 January [O.S. 10 January] 1898 in Riga, in the Governorate of Livonia, Russian Empire (present-day Latvia),[3][4] to a middle-class family. His family moved frequently in his early years, as Eisenstein continued to do throughout his life. His father, the architect Mikhail Osipovich Eisenstein, was born in the Kiev Governorate, to a Jewish merchant father, Osip, and a Swedish mother.[5][6]

Sergei Eisenstein's father had converted to the Russian Orthodox Church, while his mother, Julia Ivanovna Konetskaya, came from a Russian Orthodox family.[7] She was the daughter of a prosperous merchant.[8] Julia left Riga in the year of the 1905 Russian Revolution, taking Sergei with her to Saint Petersburg.[9] Her son would return at times to see his father, who joined them around 1910.[10] Divorce followed, and Julia left the family to live in France.[11] Eisenstein was raised as an Orthodox Christian, but later became an atheist.[12][13] Among the films that influenced Eisenstein as a child was The Consequences of Feminism (1906) by the first female filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché.[14][need quotation to verify]

Education

editAt the Petrograd Institute of Civil Engineering, Eisenstein studied architecture and engineering, the profession of his father.[15] In 1918, he left school and joined the Red Army to participate in the Russian Civil War, although his father Mikhail supported the opposite side.[16] This brought his father to Germany after the defeat of the anti-Bolshevik forces, and Sergei to Petrograd, Vologda, and Dvinsk.[17] In 1920, Sergei was transferred to a command position in Minsk, after success providing propaganda for the October Revolution. At this time, he was exposed to Kabuki theatre and studied Japanese, learning some 300 kanji characters, which he cited as an influence on his pictorial development.[18][19]

Career

editFrom theatre to cinema

editEisenstein moved to Moscow in 1920, and began his career in theatre working for Proletkult,[20] an experimental Soviet artistic institution which aspired to radically modify existing artistic forms and create a revolutionary working-class aesthetic. His productions there were entitled Gas Masks, Listen Moscow, and Enough Stupidity in Every Wise Man.[21] He worked as a designer for Vsevolod Meyerhold.[22] Eisenstein began his career as a theorist in 1923,[23] by writing "The Montage of Attractions" for art journal LEF.[24] His first film, Glumov's Diary (for the theatre production Wise Man), was also made in that same year with Dziga Vertov hired initially as an instructor.[25][26]

Strike (1925) was Eisenstein's first full-length feature film. Battleship Potemkin (also 1925) was critically acclaimed worldwide. Mostly owing to this international renown, he was then able to direct October: Ten Days That Shook the World, as part of a grand tenth anniversary celebration of the October Revolution of 1917, and then The General Line (also known as Old and New). While critics outside Soviet Russia praised these works, Eisenstein's focus in the films on structural issues such as camera angles, crowd movements, and montage brought him and like-minded others such as Vsevolod Pudovkin and Alexander Dovzhenko under fire from the Soviet film community. This forced him to issue public articles of self-criticism and commitments to reform his cinematic visions to conform to the increasingly specific doctrines of socialist realism.[citation needed]

Travels to western Europe

editIn the autumn of 1928, with October still under fire in many Soviet quarters, Eisenstein left the Soviet Union for a tour of Europe, accompanied by his perennial film collaborator Grigori Aleksandrov and cinematographer Eduard Tisse. Officially, the trip was supposed to allow the three to learn about sound motion pictures and to present themselves as Soviet artists in person to the capitalist West. For Eisenstein, however, it was an opportunity to see landscapes and cultures outside the Soviet Union. He spent the next two years touring and lecturing in Berlin, Zürich, London, and Paris.[27] In 1929, in Switzerland, Eisenstein supervised an educational documentary about abortion directed by Tisse, entitled Frauennot – Frauenglück.[28]

American projects

editIn late April 1930, film producer Jesse L. Lasky, on behalf of Paramount Pictures, offered Eisenstein the opportunity to make a film in the United States.[29] He accepted a short-term contract for $100,000 ($1,500,000 in 2017 dollars) and arrived in Hollywood in May 1930, along with Aleksandrov and Tisse.[30] Eisenstein proposed a biography of arms dealer Basil Zaharoff and a film version of Arms and the Man by George Bernard Shaw, and more fully developed plans for a film of Sutter's Gold by Blaise Cendrars,[31] but on all accounts failed to impress the studio's producers.[32] Paramount proposed a film version of Theodore Dreiser's An American Tragedy.[33] This excited Eisenstein, who had read and liked the work, and had met Dreiser at one time in Moscow. Eisenstein completed a script by the start of October 1930,[34] but Paramount disliked it and, additionally, they found themselves attacked by Major Pease,[35] president of the Hollywood Technical Director's Institute. Pease, a strident anti-communist, mounted a public campaign against Eisenstein. On October 23, 1930, by "mutual consent", Paramount and Eisenstein declared their contract null and void, and the Eisenstein party were treated to return tickets to Moscow at Paramount's expense.[36]

Eisenstein was faced with being seen a failure in the USSR. The Soviet film industry was solving the sound-film issue without him; in addition, his films, techniques and theories, such as his formalist film theory, were becoming increasingly attacked as "ideological failures". Many of his theoretical articles from this period, such as Eisenstein on Disney, have surfaced decades later.[37]

Eisenstein and his entourage spent considerable time with Charlie Chaplin,[38] who recommended that Eisenstein meet with a sympathetic benefactor, the American socialist author Upton Sinclair.[39] Sinclair's works had been accepted by and were widely read in the USSR, and were known to Eisenstein. The two admired each other, and between the end of October 1930 and Thanksgiving of that year, Sinclair had secured an extension of Eisenstein's absences from the USSR, and permission for him to travel to Mexico. Eisenstein had long been fascinated by Mexico and had wanted to make a film about the country. As a result of their discussions with Eisenstein and his colleagues, Sinclair, his wife Mary, and three other investors organized as the "Mexican Film Trust" to contract the three Russians to make a film about Mexico of Eisenstein's design.[40]

Mexican odyssey

editOn 24 November 1930, Eisenstein signed a contract with the Trust "upon the basis of his desire to be free to direct the making of a picture according to his own ideas of what a Mexican picture should be, and in full faith in Eisenstein's artistic integrity."[41] The contract stipulated that the film would be "non-political", that immediately available funding came from Mary Sinclair in an amount of "not less than Twenty-Five Thousand Dollars",[42] that the shooting schedule amounted to "a period of from three to four months",[42] and most importantly that: "Eisenstein furthermore agrees that all pictures made or directed by him in Mexico, all negative film and positive prints, and all story and ideas embodied in said Mexican picture, will be the property of Mrs. Sinclair..."[42] A codicil to the contract allowed that the "Soviet Government may have the [finished] film free for showing inside the U.S.S.R."[43] Reportedly, it was verbally clarified that the expectation was for a finished film of about an hour's duration.[citation needed]

By 4 December, Eisenstein was traveling to Mexico by train, accompanied by Aleksandrov and Tisse, and also by Mrs. Sinclair's brother, Hunter Kimbrough, a banker with no prior experience in motion picture work, who was to serve as production supervisor. At their departure Eisenstein had not yet determined a direction or subject for his film, and only several months later produced a brief outline of a six-part film; this, he promised, would be developed, in one form or another, into a final plan he would settle on for his project. The title for the project, ¡Que viva México!, was decided on some time later still. While in Mexico, he mixed socially with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; Eisenstein admired these artists and Mexican culture in general, and they inspired him to call his films "moving frescoes".[44] The left-wing U.S. film community eagerly followed his progress within Mexico, as is chronicled within Chris Robe's book Left of Hollywood: Cinema, Modernism, and the Emergence of U.S. Radical Film Culture.[45]

Filming was not accomplished in the 3–4 months agreed to in Eisenstein's contract, however, and the Trust was running out of money; and his prolonged absence from the USSR led Joseph Stalin to send a telegram to Sinclair expressing the concern that Eisenstein had become a deserter.[46] Under pressure, Eisenstein blamed Mary Sinclair's younger brother, Hunter Kimbrough, who had been sent along to act as a line producer, for the film's problems.[47] Eisenstein hoped to pressure the Sinclairs to insinuate themselves between him and Stalin, so Eisenstein could finish the film in his own way. Unable to raise further funds, and under pressure from both the Soviet government and the majority of the Trust, Sinclair shut down production and ordered Kimbrough to return to the United States with the remaining film footage and the three Soviets to see what they could do with the film already shot; estimates of the extent of this range from 170,000 lineal feet with Soldadera unfilmed,[48] to an excess of 250,000 lineal feet.[49] For the unfinished filming of the "novel" of Soldadera, without incurring any cost, Eisenstein had secured 500 soldiers, 10,000 guns, and 50 cannons from the Mexican Army.[47]

When Kimbrough arrived at the American border, a customs search of his trunk revealed sketches and drawings by Eisenstein of Jesus caricatures amongst other lewd pornographic material, which Eisenstein had added to his luggage without Kimbrough's knowledge.[50][51] His re-entry visa had expired,[52] and Sinclair's contacts in Washington were unable to secure him an additional extension. Eisenstein, Aleksandrov, and Tisse were allowed, after a month's stay at the U.S.-Mexico border outside Laredo, Texas, a 30-day "pass" to get from Texas to New York and thence depart for Moscow, while Kimbrough returned to Los Angeles with the remaining film.[52]

Eisenstein toured the American South instead of going directly to New York. In mid-1932, the Sinclairs were able to secure the services of Sol Lesser, who had just opened his distribution office in New York, Principal Distributing Corporation. Lesser agreed to supervise post-production work on the miles of negative — at the Trust's expense — and distribute any resulting product. Two short feature films and a short subject—Thunder Over Mexico based on the "Maguey" footage,[53] Eisenstein in Mexico, and Death Day respectively—were completed and released in the United States between the autumn of 1933 and early 1934. Eisenstein never saw any of the Sinclair-Lesser films, nor a later effort by his first biographer, Marie Seton, called Time in the Sun,[54] released in 1940. He would publicly maintain that he had lost all interest in the project. In 1978, Gregori Aleksandrov released – with the same name in contravention to the copyright – his own version, which was awarded the Honorable Golden Prize at the 11th Moscow International Film Festival in 1979. Later, in 1998, Oleg Kovalov edited a free version of the film, calling it "Mexican Fantasy".[citation needed]

Return to the Soviet Union

editEisenstein's failure in Mexico took a toll on his mental health. He spent some time in a mental hospital in Kislovodsk in July 1933,[55] ostensibly a result of depression born of his final acceptance that he would never be allowed to edit the Mexican footage.[56] He was subsequently assigned a teaching position at the State Institute of Cinematography where he had taught earlier, and in 1933 and 1934 was in charge of writing the curriculum.[57]

In 1935, Eisenstein was assigned another project, Bezhin Meadow, but it appears the film was afflicted with many of the same problems as ¡Que viva México!. Eisenstein unilaterally decided to film two versions of the scenario, one for adult viewers and one for children; failed to define a clear shooting schedule; and shot film prodigiously, resulting in cost overruns and missed deadlines. Boris Shumyatsky, the de facto head of the Soviet film industry, called a halt to the filming and cancelled further production. What appeared to save Eisenstein's career at this point was that Stalin ended up taking the position that the Bezhin Meadow catastrophe, along with several other problems facing the industry at that point, had less to do with Eisenstein's approach to filmmaking as with the executives who were supposed to have been supervising him. Ultimately this came down on the shoulders of Shumyatsky,[58] who in early 1938 was denounced, arrested, tried and convicted as a traitor, and shot.

Comeback

editEisenstein was able to ingratiate himself with Stalin for 'one more chance', and he chose, from two offerings, the assignment of a biopic of Alexander Nevsky and his victory at the Battle of the Ice, with music composed by Sergei Prokofiev.[59] This time, he was assigned a co-scenarist, Pyotr Pavlenko,[60] to bring in a completed script; professional actors to play the roles; and an assistant director, Dmitri Vasilyev, to expedite shooting.[60]

The result was a film critically well received by both the Soviets and in the West, which won him the Order of Lenin and the Stalin Prize.[61] It was an allegory and stern warning against the massing forces of Nazi Germany, well played and well made. The script had Nevsky utter a number of traditional Russian proverbs, verbally rooting his fight against the Germanic invaders in Russian traditions.[62] This was started, completed, and placed in distribution all within the year 1938, and represented Eisenstein's first film in nearly a decade and his first sound film.[citation needed]

Eisenstein returned to teaching, and was assigned to direct Richard Wagner's Die Walküre at the Bolshoi Theatre.[61] After the outbreak of war with Germany in 1941, Alexander Nevsky was re-released with a wide distribution and earned international success. With the war approaching Moscow, Eisenstein was one of many filmmakers evacuated to Alma-Ata, where he first considered the idea of making a film about Tsar Ivan IV. Eisenstein corresponded with Prokofiev from Alma-Ata, and was joined by him there in 1942. Prokofiev composed the score for Eisenstein's film Ivan the Terrible and Eisenstein reciprocated by designing sets for an operatic rendition of War and Peace that Prokofiev was developing.[63]

Ivan trilogy

editEisenstein's film Ivan the Terrible, Part I, presenting Ivan IV of Russia as a national hero, won Stalin's approval (and a Stalin Prize),[64] but the sequel, Ivan the Terrible, Part II, was criticized by various authorities and went unreleased until 1958. All footage from Ivan the Terrible, Part III was confiscated by the Soviet authorities whilst the film was still incomplete, and most of it was destroyed, though several filmed scenes exist.[65][66]

Personal life

editThere have been debates about Eisenstein's sexuality, with a film covering Eisenstein's homosexuality running into difficulties in Russia.[67][68]

Almost all of his contemporaries believed that Eisenstein was gay. During a 1925 interview, Aleksandrov witnessed Eisenstein tell the Polish journalist Waclaw Solski, "I'm not interested in girls" and burst out laughing, then quickly stopped and turned red with embarrassment. Recalling the incident, Solski wrote "Not until later, when I learned what everyone in Moscow knew, did Aleksandrov's odd behaviour become understandable."[69] Upton Sinclair came to the same conclusion after the discovery of Eisenstein's pornographic drawings by customs officials. He later told Marie Seton: "All his associates were Trotskyites, and all homos ... Men of that sort stick together."[70]

Seven months after homosexuality became a criminal offence, Eisenstein married filmmaker and screenwriter Pera Atasheva (born Pearl Moiseyevna Fogelman; 1900 – 24 September 1965).[71][72][73] Aleksandrov married Orlova during that same year.

Eisenstein confessed his asexuality to his close friend Marie Seton: "Those who say that I am homosexual are wrong. I have never noticed and do not notice this. If I was homosexual I would say so, directly. But the whole point is that I have never experienced a homosexual attraction, even towards Grisha, despite the fact I have some bisexual tendency in the intellectual dimension like, for example, Balzac or Zola."[74]

Death

editEisenstein suffered a heart attack on 2 February 1946, and spent much of the following year recovering. He died of a second heart attack on 11 February 1948, at the age of 50.[75] His body lay in state in the Hall of the Cinema Workers before being cremated on 13 February, and his ashes were buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.[76]

Film theorist

editEisenstein was among the earliest film theorists. He briefly attended the film school established by Lev Kuleshov and the two were both fascinated with the power of editing to generate meaning and elicit emotion. Their individual writings and films are the foundations upon which Soviet montage theory was built, but they differed markedly in their understanding of its fundamental principles. Eisenstein's articles and books—particularly Film Form and The Film Sense—explain the significance of montage in detail.

His writings and films have continued to have a major impact on subsequent filmmakers. Eisenstein believed that editing could be used for more than just expounding a scene or moment, through a "linkage" of related images—as Kuleshov maintained. Eisenstein felt the "collision" of shots could be used to manipulate the emotions of the audience and create film metaphors. He believed that an idea should be derived from the juxtaposition of two independent shots, bringing an element of collage into film. He developed what he called "methods of montage":

With his cross-disciplinary approach, he defined the montage as the constructing act par excellence at the base of every work of art: "the principle of segmentation of the object into different camera cuts" and the unification in a generalized or complete image is what we can call the peculiarity of montage as constructive process, which "leaves the event intact (the caught reality) and at the same time interprets it differently."[82]

Eisenstein taught film-making during his career at VGIK where he wrote the curricula for the directors' course;[83] his classroom illustrations are reproduced in Vladimir Nizhniĭ's Lessons with Eisenstein. Exercises and examples for students were based on rendering literature such as Honoré de Balzac's Le Père Goriot.[84] Another hypothetical was the staging of the Haitian struggle for independence as depicted in Anatolii Vinogradov's The Black Consul,[85] influenced as well by John Vandercook's Black Majesty.[86]

Lessons from this scenario delved into the character of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, replaying his movements, actions, and the drama surrounding him. Further to the didactics of literary and dramatic content, Eisenstein taught the technicalities of directing, photography, and editing, while encouraging his students' development of individuality, expressiveness, and creativity.[87] Eisenstein's pedagogy, like his films, was politically charged and contained quotes from Vladimir Lenin interwoven with his teaching.[88]

In his initial films, Eisenstein did not use professional actors. His narratives eschewed individual characters and addressed broad social issues, especially class conflict. He used groups as characters, and the roles were filled with untrained people from the appropriate classes; he avoided casting stars.[89] Like many Bolshevik artists, Eisenstein envisioned a new society which would subsidize artists, freeing them from the confines of capitalism, leaving them absolutely free to create, but due to the material conditions at the time, budgets and producers were as significant to the Soviet film industry as the rest of the world.

Drawings

editEisenstein kept sketchbooks throughout his life. After his death, his widow, Pera Atasheva, gave most of them to the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI) – but withheld over 500 erotic drawings from the donation. She later passed these drawings to Andrei Moskvin for safekeeping, and after perestroika Moskvin's heirs sold them abroad. The erotic drawings have been the subject of several exhibitions since the late 1990s. Some are reproduced in Joan Neuberger's essay "Strange Circus: Eisenstein's Sex Drawings."[90]

Honours and awards

edit- Two Stalin Prizes – 1941 for the film Alexander Nevsky (1938), 1946 for the first film of the series Ivan the Terrible (1944)[91]

- Honored Artist of the RSFSR (1935)[92]

- Order of Lenin (1939) – for the film Alexander Nevsky (1938)[91]

- Order of the Badge of Honour[92]

Influence

editIn 2023, notable artist William Kentridge included a drawing of Eisenstein in his solo museum exhibition at The Broad in Los Angeles.[93]

Tribute

editOn January 22, 2018, Google celebrated his 120th birthday with a Google Doodle.[94]

Filmography

edit- 1923 "Дневник Глумова" ("Glumov's Diary", short)

- 1925 Стачка (Strike)

- 1925 Броненосец Потёмкин (Battleship Potemkin)

- 1928 Октябрь «Десять дней, которые потрясли мир» (October: Ten Days That Shook the World)

- 1929 Буря над Ла Сарра (The Storming of La Sarraz, with Ivor Montagu and Hans Richter, lost)

- 1929 Старое и новое «Генеральная линия» (The General Line, also known as Old and New)

- 1930 "Romance sentimentale" (France, short)

- 1931 "El Desastre en Oaxaca" (Mexico, short)

- 1938 Александр Невский (Alexander Nevsky)

- 1944 Иван Грозный 1-я серия (Ivan the Terrible, Part I)

- 1958 Иван Грозный 2-я серия (Ivan the Terrible, Part II, completed in 1946)

Unfinished films

edit- 1932 Да здравствует Мексика! (¡Que viva México!, reconstructed in 1979)

- 1937 Бежин луг (Bezhin Meadow, reconstructed in the 1960s using storyboards and a new soundtrack)

Other work

edit- 1929 "Frauennot – Frauenglück" ("Women's Misery – Women's Happiness", also known as "Misery and Fortune of Woman") (Switzerland)[95] – Eisenstein worked as supervisor

Bibliography

edit- Selected articles in: Christie, Ian; Taylor, Richard, eds. (1994), The Film Factory: Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents, 1896–1939, New York, NY: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-05298-X.

- Eisenstein, Sergei (1949), Film Form: Essays in Film Theory, New York: Hartcourt; translated by Jay Leyda.

- Eisenstein, Sergei (1942), The Film Sense, New York: Hartcourt; translated by Jay Leyda.

- Eisenstein, Sergei (1959), Notes of a film director, Foreign Languages Pub. House; translated by X. Danko Online version

- Eisenstein, Sergei (1972), Que Viva Mexico!, New York: Arno, ISBN 978-0-405-03916-4.

- Eisenstein, Sergei (1994), Towards a Theory of Montage, British Film Institute.

- In Russian, and available online

- Эйзенштейн, Сергей (1968), "Сергей Эйзенштейн" (избр. произв. в 6 тт), Москва: Искусство, Избранные статьи.

Notes

edit- ^ Russian: Сергей Михайлович Эйзенштейн, romanized: Sergey Mikhaylovich Eyzenshteyn, IPA: [sʲɪrˈɡʲej mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪtɕ ɪjzʲɪnˈʂtʲejn]; in this name that follows Eastern Slavic naming customs, the patronymic is Mikhailovich and the family name is Eisenstein.

References

edit- ^ Rollberg, Peter (2009). Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Cinema. US: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 204–210. ISBN 978-0-8108-6072-8.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Films of All Time | Sight & Sound". Archived from the original on August 2, 2012.

- ^ Mitry, Jean (7 February 2020). "Sergey Eisenstein – Soviet film director". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 May 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ "Sergei Eisenstein – Russian film director and film theorist. Biography and interesting facts". 22 July 2017. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 9 November 2018.

- ^ "Зашифрованное зодчество Риги". Archived from the original on 30 April 2019.

- ^ Роман Соколов, Анна Сухорукова «Новые данные о предках Сергея Михайловича Эйзенштейна»: «Киноведческие записки» 102/103, 2013; стр. 314—323.

- ^ Эйзенштейн 1968 [1].

- ^ Bordwell 1993, p. 1.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 19.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 20.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 22.

- ^ LaValley, Al (2001). Eisenstein at 100. Rutgers University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780813529714.

As a committed Marxist, Eisenstein outwardly turned his back on his Orthodox upbringing, and took pains in his memoirs to stress his atheism.

- ^ Eisenstein, Sergei (1996). Taylor, Richard (ed.). Beyond the stars: the memoirs of Sergei Eisenstein, Volume 5. BFI Publishing. p. 414. ISBN 9780851704609.

My atheism is like that of Anatole France -- inseparable from adoration of the visible forms of a cult.

- ^ Eisenstein, Sergei (2019). Yo. Memoirs. Russia: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art. pp. 283, 443.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 28.

- ^ Seton 1952, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 35.

- ^ Эйзенштейн 1968 [2]

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 37.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 41.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 529.

- ^ Seton 1952, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 61.

- ^ Christie & Taylor 1994, pp. 87–89

- ^ Эйзенштейн 1968 [3].

- ^ Goodwin 1993, p. 32.

- ^ Eisenstein 1972, p. 8.

- ^ Bordwell 1993, p. 16.

- ^ Geduld & Gottesman 1970, p. 12.

- ^ "Alexander Dobtovinsky: I will personally publish the "Vnukovo Archive" of Lyubov Orlova and Grigory Alexandrov". bfmspb.ru (in Russian). Business FM. 14 November 2019. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Montagu 1968, p. 151.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 172.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 174.

- ^ Montagu 1968, p. 209.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 167.

- ^ Seton 1952, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Eisenstein, Sergei (1986). Leyda, Jay (ed.). Sergei Eisenstein on Disney. Translated by Upchurch, Alan Y. Calcutta: Seagull Books. ISBN 978-0-85742-491-4. OCLC 990846648.

- ^ Montagu 1968, pp. 89–97.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 187.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 188.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 189.

- ^ a b c Geduld & Gottesman 1970, p. 22.

- ^ Geduld & Gottesman 1970, p. 23.

- ^ Bordwell 1993, p. 19.

- ^ Left of Hollywood: Cinema, Modernism, and the Emergence of U.S. Radical Film Culture

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 513.

- ^ a b Geduld & Gottesman 1970, p. 281.

- ^ Eisenstein 1972, p. 14.

- ^ Geduld & Gottesman 1970, p. 132.

- ^ Seton 1952, pp. 234–235.

- ^ Geduld & Gottesman 1970, pp. 309–310.

- ^ a b Geduld & Gottesman 1970, p. 288.

- ^ Bordwell 1993, p. 21.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 446.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 280.

- ^ Leyda 1960, p. 299.

- ^ Bordwell 1993, p. 140.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 369.

- ^ González Cueto, Irene (2016-05-23). "Warhol, Prokofiev, Eisenstein y la música – Cultural Resuena". Cultural Resuena (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ^ a b Bordwell 1993, p. 27.

- ^ a b Bordwell 1993, p. 28.

- ^ Kevin McKenna. 2009. "Proverbs and the Folk Tale in the Russian Cinema: The Case of Sergei Eisenstein's Film Classic Aleksandr Nevsky." The Proverbial «Pied Piper» A Festschrift Volume of Essays in Honor of Wolfgang Mieder on the Occasion of His Sixty-Fifth Birthday, ed. by Kevin McKenna, pp. 277–92. New York, Bern: Peter Lang.

- ^ Leyda & Voynow 1982, p. 146.

- ^ Neuberger 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Leyda & Voynow 1982, p. 135.

- ^ Blois, Beverly. "Eisenstein's "Ivan The Terrible, Part II" as Cultural Artifact" (PDF).

- ^ Gray, Carmen (2015-03-30). "Greenaway offends Russia with film about Soviet director's gay affair". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ^ McNabb, Geoffrey (2015-02-09). "Film claiming director Sergei Eisenstein had gay love affair shunned". The Independent. Retrieved 2020-07-09.

- ^ McSmith, Andy (2015). Fear and the Muse Kept Watch, The Russian Masters – from Akhmatova and Pasternak to Shostakovich and Eisenstein – Under Stalin. New York: The New Press. pp. 160–61. ISBN 978-1-59558-056-6.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 515.

- ^ Bordwell 1993, p. 33.

- ^ "Pera Atasheva" (in Russian). Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ "СЮЖЕТ МОГИЛА СЕРГЕЯ ЭЙЗЕНШТЕЙНА, ВОЗЛОЖЕНИЕ ЦВЕТОВ. (1998)".

- ^ ""Intellectual Orientation". Sergey Eisenstein's offscreen life". aif.ru (in Russian). Argumenty i Facty. 22 January 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ^ Neuberger 2003, p. 23.

- ^ Cavendish, Richard. "The Death of Sergei Eisenstein". Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Eisenstein 1949, p. 72.

- ^ Eisenstein 1949, p. 73.

- ^ Eisenstein 1949, p. 75.

- ^ Eisenstein 1949, p. 78.

- ^ Eisenstein 1949, p. 82.

- ^ Eisenstein, Sergei (1963–1970). "Montăz", in Izbrannye proizvedenija v šesti tomach, (vol. II) [tr. it. Teoria generale del montaggio, Venezia, Marsilio, 1985] (in Italian). Moscow: Iskusstvo. p. 216.

- ^ Nizhniĭ 1962, p. 93.

- ^ Nizhniĭ 1962, p. 3.

- ^ Nizhniĭ 1962, p. 21

- ^ Leyda & Voynow 1982, p. 74.

- ^ Nizhniĭ 1962, pp. 148–155.

- ^ Nizhniĭ 1962, p. 143.

- ^ Seton 1952, p. 185.

- ^ Neuberger, Joan (2012-07-02). "Strange circus: Eisenstein's sex drawings". Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema. 6 (1): 5–52. doi:10.1386/srsc.6.1.5_1. S2CID 144328625.

- ^ a b Neuberger, Joan (2003). Ivan the Terrible: The Film Companion. I.B.Tauris. pp. 2, 9. ISBN 9781860645600. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Sergei Eisenstein – Father of Montage". Artland Magazine. 2020-01-10. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- ^ Amadour (2022-12-07). "15 Minutes With Visionary Artist William Kentridge". LAmag – Culture, Food, Fashion, News & Los Angeles. Retrieved 2023-12-31.

- ^ "Sergei Eisenstein's 120th Birthday". Google. 27 February 2024.

- ^ "Misery and Fortune of Women | BAMPFA". bampfa.org. 18 January 2018. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

Sources

edit- Bergan, Ronald (1999), Sergei Eisenstein: A Life in Conflict, Boston, MA: Overlook Hardcover, ISBN 978-0-87951-924-7

- Bordwell, David (1993), The Cinema of Eisenstein, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-13138-5

- Geduld, Harry M.; Gottesman, Ronald, eds. (1970), Sergei Eisenstein and Upton Sinclair: The Making & Unmaking of Que Viva Mexico!, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-253-18050-6

- Goodwin, James (1993), Eisenstein, Cinema, and History, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-06269-8

- Leyda, Jay (1960), Kino: A History of the Russian And Soviet Film, New York: Macmillan, OCLC 1683826

- Eisenstein, Sergei (1986), Leyda, Jay (ed.), Sergei Eisenstein on Disney, translated by Upchurch, Alan Y., Calcutta: Seagull Books, ISBN 978-0-85742-491-4, OCLC 990846648

- Leyda, Jay; Voynow, Zina (1982), Eisenstein At Work, New York: Pantheon, ISBN 978-0-394-74812-2

- Montagu, Ivor (1968), With Eisenstein in Hollywood, Berlin: Seven Seas Books, OCLC 8713

- Neuberger, Joan (2003), Ivan the Terrible: The Film Companion, London; New York: I.B. Tauris, ISBN 1-86064-560-7

- Nizhniĭ, Vladimir (1962), Lessons with Eisenstein, New York: Hill and Wang, OCLC 6406521

- Seton, Marie (1952), Sergei M. Eisenstein: A Biography, New York: A.A. Wyn, OCLC 2935257

- Howes, Keith (2002), "Eisenstein, Sergei (Mikhailovich)", in Aldrich, Robert; Wotherspoon, Garry (eds.), Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History from Antiquity to World War II, Routledge; London, ISBN 0-415-15983-0

- Stern, Keith (2009), "Eisenstein, Sergei", Queers in History, BenBella Books, Inc.; Dallas, TX, ISBN 978-1-933771-87-8

- Antonio Somaini, Ejzenstejn. Il cinema, le arti, il montaggio (Eisenstein. Cinema, the Arts, Montage), Einaudi, Torino 2011

Documentaries

edit- The Secret Life of Sergei Eisenstein (1987) by Gian Carlo Bertelli

Filmed biographies

edit- Eisenstein (2000) by Renny Bartlett, "a series of loosely connected (and unevenly acted) theatrical sketches whose central theme is the director's shifting relationship with the Soviet government" focusing on "Eisenstein the political animal, gay man, Jewish target and artistic rebel".

- Eisenstein in Guanajuato (2015) by Peter Greenaway.

Further reading

edit- Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein Collection is housed at the Museum of Modern Art Museum Archives.

- Sergei Eisenstein Scrapbook of photographs and manuscripts [ca. 1900]-1930 (2 volumes) is house at the Museum of Modern Art Museum Archives.

- Sergei Eisenstein Correspondence with Theodore Dreiser, 1931–1941 (9 letters), is housed at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at the University of Pennsylvania.

External links

edit- Sergei Eisenstein in Senses of Cinema

- Sergei Eisenstein at IMDb

- Discussion with Stalin regarding Ivan the Terrible

- Sergei Eisenstein Is Dead In Moscow; New York Times

- Sergei Eisenstein at Find a Grave

- "Glumov's Diary" – 1923 – Sergei Eisenstein's first film on YouTube

- Sergei Eisenstein and the Haitian Revolution by Charles Forsdick and Christian Hogsbjerg, History Workshop Journal, 78 (2014).

- Sergei Eisenstein on Google Arts and Culture