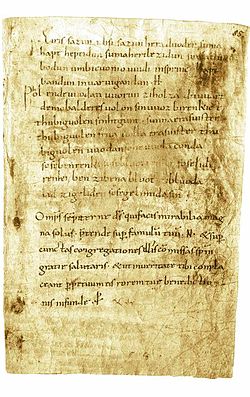

The Merseburg charms, Merseburg spells, or Merseburg incantations (German: die Merseburger Zaubersprüche) are two medieval magic spells, charms or incantations, written in Old High German. They are the only known examples of Germanic pagan belief preserved in the language. They were discovered in 1841 by Georg Waitz,[1] who found them in a theological manuscript from Fulda, written in the 9th century,[2] although there remains some speculation about the date of the charms themselves. The manuscript (Cod. 136 f. 85a) is stored in the library of the cathedral chapter of Merseburg, hence the name.

History

editThe Merseburg charms are the only known surviving relics of pre-Christian, pagan poetry in Old High German literature.[3]

The charms were recorded in the 10th century by a cleric, possibly in the abbey of Fulda, on a blank page of a liturgical book, which later passed to the library at Merseburg. The charms have thus been transmitted in Caroline minuscule on the flyleaf of a Latin sacramentary.

The spells became famous in modern times through the appreciation of Jacob Grimm, who wrote as follows:

- Lying between Leipzig, Halle and Jena, the extensive library of the Cathedral Chapter of Merseburg has often been visited and made use of by scholars. All have passed over a codex which, if they chanced to take it up, appeared to offer only well-known church items, but which now, valued according to its entire content, offers a treasure such that the most famous libraries have nothing to compare with it...[4]

The spells were published later by Jacob Grimm in On two newly-discovered poems from the German Heathen Period (1842).

The manuscript of the Merseburg charms was on display until November 2004 as part of the exhibition "Between Cathedral and World - 1000 years of the Chapter of Merseburg," at Merseburg cathedral. They were previously exhibited in 1939.[citation needed]

The texts

editEach charm is divided into two parts: a preamble telling the story of a mythological event; and the actual spell in the form of a magic analogy (just as it was before... so shall it also be now...). In their verse form, the spells are of a transitional type; the lines show not only traditional alliteration but also the end-rhymes introduced in the Christian verse of the 9th century.[5]

First Merseburg Charm

editThe first spell is a "Lösesegen" (blessing of release), describing how a number of "Idisen" freed from their shackles warriors caught during battle.[6] The last two lines contain the magic words "Leap forth from the fetters, escape from the foes" that are intended to release the warriors.

Eiris sazun idisi, |

Once sat women, |

Second Merseburg Charm

editPhol is with Wodan when Balder's horse dislocates its foot while he is riding through the forest (holza). Wodan intones the incantation: "Bone to bone, blood to blood, limb to limb, as if they were mended".

Figures that can be clearly identified within Continental Germanic mythology are "Uuôdan" (Wodan) and "Frîia" (Frija). Depictions found on Migration Period Germanic bracteates are often viewed as Wodan (Odin) healing a horse.[9]

Comparing Norse mythology, Wodan is well-attested as the cognate of Odin. Frija is the cognate of Frigg.[10] Balder is Norse Baldr. Phol is possibly the masculine form of Uolla. According to Jacob Grimm, the context would make it clear that it is another name for Balder.[11] The identification with Balder is not conclusive. Modern scolarship suggests that Freyr might be meant.[12] Uolla is cognate with Old Norse Fulla, a goddess there also associated with Frigg.[13] Sunna (the personified sun) is in Norse mythology Sól. Sinthgunt is otherwise unattested.[14]

Phol ende uuodan |

Phol and Wodan were riding to the woods, |

Parallels

editThe First Merseburg Charm (loosening charm)'s similarity to the anecdote in Bede's Hist. Eccles., IV, 22 ( "How a certain captive's chains fell off when masses were sung for him") has been noted by Jacob Grimm.[17] In this Christianized example, it is the singing of the mass, rather than the chanting of the charm, that effects the release of a comrade (in this case a brother). The unshackled man is asked "whether he had any spells about him, as are spoken of in fabulous stories",[18] which curiously has been translated as "loosening rune (about him)" (Old English: álýsendlícan rune) in the Anglo-Saxon translation of Bede, as has been pointed out by Sophus Bugge. Bugge makes this reference in his edition of the Eddaic poem Grógaldr (1867), in an attempt to justify his emending the phrase "Leifnir's fire (?)" (Old Norse: leifnis elda) into "loosening charm" (Old Norse: leysigaldr) in the context of one of the magic charms that Gróa is teaching to her son.[19] But this is an aggressive emendation of the original text, and its validity as well as any suggestion to its ties to the Merseburg charm is subject to skepticism.[20][a]

Many analogous magic incantations to the Second Merseburg Charm (horse-healing spell) have been noted. Some paralleling is discernible in other Old German spells, but analogues are particularly abundant in folkloric spells from Scandinavian countries (often preserved in so-called "black books"). Similar charms have been noted in Gaelic, Lettish and Finnish[22] suggesting that the formula is of ancient Indo-European origin.[citation needed] Parallels have also been suggested with Hungarian texts.[23] Some commentators trace the connection back to writings in ancient India.

Other Old High German and Old Saxon spells

editOther spells recorded in Old High German or Old Saxon noted for similarity, such as the group of wurmsegen spells for casting out the "Nesso" worm causing the affliction.[17] There are several manuscript recensions of this spell, and Jacob Grimm scrutinizes in particular the so-called "Contra vermes" variant, in Old Saxon[24] from the Cod. Vindob. theol. 259[17] (now ÖNB Cod. 751[25]). The title is Latin:

Contra vermes (against worms[24])

Gang ût, nesso, mit nigun nessiklînon,

ût fana themo margę an that bên, fan themo bêne an that flêsg,

ût fana themo flêsgke an thia hûd, ût fan thera hûd an thesa strâla.

Drohtin, uuerthe so![26]

As Grimm explains, the spell tells the nesso worm and its nine young ones to begone, away from the marrow to bone, bone to flesh, flesh to hide (skin), and into the strâla or arrow, which is the implement into which the pest or pathogen is to be coaxed.[17] It closes with the invocation: "Lord (Drohtin), let it be".[24] Grimm insists that this charm, like the De hoc quod Spurihalz dicunt charm (MHG: spurhalz; German: lahm "lame") that immediately precedes it in the manuscript, is "about lame horses again" And the "transitions from marrow to bone (or sinews), to flesh and hide, resemble phrases in the sprain-spells", i.e. the Merseburg horse-charm types.

Scandinavia

editJacob Grimm in his Deutsche Mythologie, chapter 38, listed examples of what he saw as survivals of the Merseburg charm in popular traditions of his time: from Norway a prayer to Jesus for a horse's leg injury, and two spells from Sweden, one invoking Odin (for a horse suffering from a fit or equine distemper[27][b]) and another invoking Frygg for a sheep's ailment.[17] He also quoted one Dutch charm for fixing a horse's foot, and a Scottish one for the treatment of human sprains that was still practiced in his time in the 19th century (See #Scotland below).

Norway

editGrimm provided in his appendix another Norwegian horse spell,[17] which has been translated and examined as a parallel by Thorpe.[27] Grimm had recopied the spell from a tome by Hans Hammond, Nordiska Missions-historie (Copenhagen 1787), pp. 119–120, the spell being transcribed by Thomas von Westen c. 1714.[28] This appears to be the same spell in English as given as a parallel by a modern commentator, though he apparently misattributes it to the 19th century.[29] The texts and translations will be presented side-by-side below:

- LII. gegen knochenbruch[30]

- Jesus reed sig til Heede,

- der reed han syndt sit Folebeen.

- Jesus stigede af og lägte det;

- Jesus lagde Marv i Marv,

- Ben i Ben, Kjöd i Kjöd;

- Jesus lagde derpaa et Blad,

- At det skulde blive i samme stad.

- i tre navne etc.

- (Hans Hammond, "Nordiska Missions-historie",

- Kjøbenhavn 1787, pp.119, 120)[31]

- (= Bang's formula #6)[32]

- ---

- Jesus rode to the heath,

- There he rode the leg of his colt in two.

- Jesus dismounted and heal'd it;

- Jesus laid marrow to marrow,

- Bone to bone, flesh to flesh;

- Jesus laid thereon a leaf,

- That it might remain in the same place.

(Thorpe tr.)[27]

- For a Broken Bone

- Jesus himself rode to the heath,

- And as he rode, his horse's bone was broken.

- Jesus dismounted and healed that:

- Jesus laid marrow to marrow,

- Bone to bone, flesh to flesh.

- Jesus thereafter laid a leaf

- So that these should stay in their place.[29][c]

- (in the Three Names, etc.)

(Stone(?) tr.)

The number of Norwegian analogues is quite large, though many are just variations on the theme. Bishop Anton Christian Bang compiled a volume culled from Norwegian black books of charms and other sources, and classified the horse-mending spells under the opening chapter "Odin og Folebenet", strongly suggesting a relationship with the second Merseburg incantation.[33] Bang here gives a group of 34 spells, mostly recorded in the 18th–19th century though two are assigned to the 17th (c. 1668 and 1670),[28] and 31 of the charms[34] are for treating horses with an injured leg. The name for the horse's trauma, which occurs in the titles, is Norwegian: vred in most of the rhymes, with smatterings of raina and bridge (sic.), but they all are essentially synonymous with brigde, glossed as the "dislocation of the limb" [d] in Aasen's dictionary.[34][35]

From Bishop Bang's collection, the following is a list of specific formulas discussed as parallels in scholarly literature:

- No. 2, "Jesus og St. Peter over Bjergene red.." (c. 1668. From Lister og Mandal Amt, or the modern-day Vest-Agder. Ms. preserved at the Danish Rigsarkivet)[36]

- No. 6, Jesus red sig tile Hede.." (c. 1714. Veø, Romsdal). Same as Grimm's LII quoted above.[37][38]

- No, 20, "Jeus rei sin Faale over en Bru.." (c. 1830. Skåbu, Oppland. However Wadstein's paper does not focus the study on the base text version, but the variant Ms. B which has the "Faale" spelling)[39]

- No. 22, "Vor Herre rei.." (c. 1847. Valle, Sætersdal. Recorded by Jørgen Moe)[40][e]

It might be pointed out that none of the charms in Bang's chapter "Odin og Folebenet" actually invokes Odin.[f] The idea that the charms have been Christianized and that the presence of Baldur has been substituted by "The Lord" or Jesus is expressed by Bang in another treatise,[41] crediting communications with Bugge and the work of Grimm in the matter. Jacob Grimm had already pointed out the Christ-Balder identification in interpreting the Merseburg charm; Grimm seized on the idea that in the Norse language, "White Christ (hvíta Kristr)" was a common epithet, just as Balder was known as the "white Æsir-god"[42]

Another strikingly similar "horse cure" incantation is a 20th-century sample that hails the name of the ancient 11th-century Norwegian king Olaf II of Norway. The specimen was collected in Møre, Norway, where it was presented as for use in healing a bone fracture:

- Les denne bøna:

- Sankt-Olav reid i den

- grøne skog,

- fekk skade på sin

- eigen hestefot.

- Bein i bein,

- kjøt i kjøt,

- hud i hud.

- Alt med Guds ord og amen[43]

- To Heal a Bone Fracture

- Saint Olav rode in

- green wood;

- broke his little

- horse's foot.

- Bone to bone,

- flesh to flesh,

- skin to skin.

- In the name of God,

- amen.[44]

This example too has been commented as corresponding to the second Merseburg Charm, with Othin being replaced by Saint Olav. [44]

Sweden

editSeveral Swedish analogues were given by Sophus Bugge and by Viktor Rydberg in writings published around the same time (1889). The following 17th-century spell was noted as a parallel to the Merseburg horse charm by both of them:[45][46]

- "Mot vred"

- (Sörbygdens dombok, 1672)

- Vår herre Jesus Kristus och S. Peder de gingo eller rede öfver Brattebro. S. Peders häst fick vre eller skre. Vår herre steg af sin häst med, signa S. Peders häst vre eller skre: blod vid blod, led vid led. Så fick S. Peders häst bot i 3 name o.s.v.

—Bugge and Rydberg, after Arcadius (1883)[47]

- "Against dislocations"

- (court proceeding records for Sörbygden hundred, 1672)

- Our Lord Jesus Christ and St. Peter went or rode over Brattebro. St. Peter's horse got (a dislocation or sprain). Our Lord dismounted from His horse, blessed St. Peter's horse (with the dislocation or sprain): blood to blood, (joint to joint). So received St. Peter's horse healing in three names etc. etc.

—adapted from Eng. tr. in: Nicolson 1892, Myth and Religion, p.120- and Brenner's German tr. of Bugge (1889)[g]

Another example (from Kungelf's Dombok, 1629) was originally printed by Arcadius:[48][49]

Vår herre red ad hallen ned. Hans foles fod vrednede ved, han stig aff, lagde leed ved leed, blod ved blod, kiöd ved kiöd, ben ved ben, som vor herre signet folen sin, leedt ind igjen, i naffn, o.s.v.

Rydberg, after Arcadius, (1883) ?[49]Our Lord rode down to the hall. His foal's foot became sprained, he dismounted, laid joint with joint, blood with blood, sinew with sinew, bone with bone, as our Lord blessed his foal, led in again, in the name of, etc.

A spell beginning "S(anc)te Pär och wår Herre de wandrade på en wäg (from Sunnerbo hundred, Småland 1746) was given originally by Johan Nordlander.[50]

A very salient example, though contemporary to Bugge's time, is one that invokes Odin's name:[51]

- A Sign of the Cross incantation (Danish: signeformularer)

- (from Jellundtofte socken, Västbo hundred in Småland, 19th century)

Oden rider öfver sten och bärg

han rider sin häst ur vred och i led,

ur olag och i lag, ben till ben, led till led,

som det bäst var, när det helt var.

Odin rides over rock and hill;

he rides his horse out of dislocation and into realignment

out of disorder and into order, bone to bone, joint to joint,

as it was best, when it was whole.

Denmark

editA Danish parallel noted by A. Kuhn[52] is the following:

Imod Forvridning

(Jylland)

Jesus op ad Bierget red;

der vred han sin Fod af Led.

Saa satte han sig ned at signe.

Saa sagde han:

Jeg signer Sener i Sener,

Aarer i Aarer,

Kiød i Kiød,

Og Blod i Blod!

Saa satte han Haanden til Jorden ned,

Saa lægedes hans Fodeled!

I Navnet o.s.v.

Thiele's #530[53]against dislocations

(from Jutland)

Jesus up the mountain did ride;

sprained his foot in the joint.

He sat down for a blessing,

and so said he:

I bless tendon to tendon

vein to vein,

flesh to flesh,

and blood to blood!

So he set his hand down on the ground below,

and bonded were his joints together!

In the Name, etc.[h]

Scotland

editGrimm also exemplified a Scottish charm (for people, not horses) as a salient remnant of the Merseburg type of charm.[17] This healing spell for humans was practiced in Shetland[54][55] (which has strong Scandinavian ties and where the Norn language used to be spoken). The practice involved tying a "wresting thread" of black wool with nine knots around the sprained leg of a person, and in an inaudible voice pronouncing the following:

Alexander Macbain (who also supplies a presumably reconstructed Gaelic "Chaidh Criosd a mach/Air maduinn mhoich" to the first couplet of "The Lord rade" charm above[56]) also records a version of a horse spell which was chanted while "at the same time tying a worsted thread on the injured limb".[57]

Christ went forth

In the early morn

And found the horses' legs

Broken across.

He put bone to bone.

Sinew to sinew,

Flesh to flesh.

And skin to skin;

And as He healed that,

May I heal this.(Macbain tr.) [59]

Macbain goes on to quote another Gaelic horse spell, one beginning "Chaidh Brìde mach.." from Cuairtear nan Gleann (July 1842) that invokes St. Bride as a "he" rather than "she", plus additional examples suffering from corrupted text.

Ancient India

editThere have been repeated suggestions that healing formula of the Second Merseburg Charm may well have deep Indo-European roots. A parallel has been drawn between this charm and an example in Vedic literature, an incantation from the 2nd millennium BCE found in the Atharvaveda, hymn IV, 12:[60][61][62][63]

1. róhaṇy asi róhany asthṇaç chinnásya róhaṇî

róháye 'dám arundhati

2. yát te rishṭáṃ yát te dyuttám ásti péshṭraṃ te âtmáni

dhâtấ tád bhadráyâ púnaḥ sáṃ dadhat párushâ páruḥ

3. sáṃ te majjấ majjñấ bhavatu sámu te párushâ páruḥ

sáṃ te mâmsásya vísrastaṃ sáṃ ásthy ápi rohatu

4. majjấ majjñấ sáṃ dhîyatâṃ cármaṇâ cárma rohatu

ásṛk te ásthi rohatu ṃâṇsáṃ mâṇséna rohatu

5. lóma lómnâ sáṃ kalpayâ tvacấ sáṃ kalpayâ tvácam

ásṛk te ásthi rohatu chinnáṃ sáṃ dhehy oshadhe[60]1. Grower (Rohani)[i] art thou, grower, grower of severed bone; make this grow. O arundhatī [j]

2. What of thee is torn, what of thee is inflamed (?), what of thee is crushed (?) in thyself

may Dhātar[k] excellently put that together again, joint with joint.

3. Let thy marrow come together with marrow, and thy joint together with joint;

together let what of your flesh has fallen apart, together let thy bone grow over.

4. Let marrow be put together with marrow; let skin grow with skin;

let thy blood, bone grow; let flesh grow with flesh.

5. Fit thou together hair with hair; fit together skin with skin;

let thy blood, bone grow; put together what is severed, O herb..., etc.[64]

This parallelism was first observed by Adalbert Kuhn, who attributed it to a common Indo-European origin. This idea of an origin from a common prototype is accepted by most scholars,[65] although some have argued that these similarities are accidental.[66]

The Rohani (Rōhaṇī Sanskrit: रोहणी) here apparently does not signify a deity, but rather a healing herb;[67] in fact, just an alternative name for the herb arundathi mentioned in the same strain.[68]

See also

editExplanatory notes

edit- ^ In the original text of Grógaldr, the text that Bugge emended to leysigaldr actually reads leifnis eldr". This is discussed by Rydberg as "Leifner's or Leifin's fire", and connected by him to Dietrich von Bern's fire-breath that can release the heroes from their chains.[21]

- ^ Fortunately Thorpe (1851), pp. 23–4, vol.1 provides an English translation side by side with the Swedish charm, and clarifies that the condition, in Swedish floget or the 'flog' is "horse distemper". Grimm says it corresponds to German: anflug or a "fit" in English, but it is hard to find any sources precisely defining this.

- ^ Griffiths only vaguely identifies this as a "Norwegian charm, written down in the 19th century", citing Stanley (1975), p. 84 and Stone (1993). The century dating conflicts with Grimm and Bang's attribution.

- ^ brigde Danish: Forvridning af Lemmer (dislocation of the limbs).

- ^ No. 7 and a text similar to No. 21 are used as parallels in the Norwegian Wikipedia article, no:Merseburgerformelen.

- ^ Although a couple of charms (No. 40, No. 127) among some 1550 in Bang's volume do name the pagan god.

- ^ Nicolson gives "St. Peter's horse got vre eller skre the italics he footnotes as meaning "mishandled or slipped". He also translated led vid led as "sinew to sinew", but Brenner has Glied (joint)

- ^ Wikiuser translated.

- ^ Skr. Rohani (Sanskrit: रोहणी) "grower", another name for the medicine plant arundhati mentioned in this strophe. Lincoln (1986), p. 104

- ^ Here a climbing vine; cf. Arundhati

- ^ The Creator.

Citations

edit- ^ Giangrosso 2016, p. 113.

- ^ Steinhoff 1986, p. 410.

- ^ Bostock 1976, p. 26.

- ^ Grimm 1865, p. 2.

- ^ Steinhoff 1986, p. 415.

- ^ Steinhoff 1986, p. 412.

- ^ Griffiths (2003), p. 173

- ^ Giangrosso (2016), p. 112

- ^ Lindow 2001, p. 228.

- ^ Lindow 2001, p. 128.

- ^ Steinhoff 1986, p. 413.

- ^ Wolfgang Beck: Die Merseburger Zaubersprüche, Wiesbaden 2003.

- ^ Lindow 2001, p. 132.

- ^ Bostock 1976, p. 32.

- ^ Griffiths (2003), p. 174

- ^ translation from Benjamin W. Fortson, Indo-European language and culture: an introduction, Wiley-Blackwell, 2004,ISBN 978-1-4051-0316-9, p. 325.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grimm (1884), pp. 1231–

- ^ translation based on L.C. Jane (1903); A. M. Sellar (1907) (wikisource version)

- ^ Bugge, Sophus (1867). Sæmundar Edda hins Fróda: Norroen Fornkvaedi. P. T. Mallings. p. 340.

- ^ Murdoch, Brian (1988). "But Did They Work? Interpreting the Old High German Merseburg Charms in their Medieval Context". Neuphilologische Mitteilungen. 89: 358–369., p.365, footnote. Quote: "The existence of the term "leysigaldr" in Old Norse is seductive, but does not constitute proof of the existence of these outside the realm of fiction, or that it can be applied to the Merseburg charm. "

- ^ Rydberg, Viktor (1907). Teutonic mythology. Vol. 1. Translated by Rasmus Björn Anderson. S. Sonnenschein & Co. p. 61. ISBN 9781571132406..

- ^ Christiansen, Reidar. 1914. Die finnischen und nordischen Varianten des zweiten Merseburgerspruches. (Folklore Fellows’ Communications 18.) Hamina Academia Scientiarum Fennicum.

- ^ Pócs, Éva. "A „2. merseburgi ráolvasás” magyar típusai" [Hungarian types of the 2nd Merseburg Charm]. Olvasó. Tanulmányok a 60 (2010): 272-281.

- ^ a b c Murdoch, Brian (2004). German Literature of the Early Middle Ages. Camden House. p. 61. ISBN 9781571132406.

- ^ Fath, Jacob (1884). Wegweiser zur deutschen Litteraturgeschichte. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Braune, Helm & Ebbinghaus 1994, p. 90. For additional ms. details, see (in German) – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b c Thorpe (1851), pp. 23–4, vol.1, text and translation. Lacks the last invocational line

- ^ a b Bang (1901–1902), chapter 1, Spell #4

- ^ a b Griffiths (2003), p. 174

- ^ Numeral and German title is Grimm's

- ^ Grimm (1888), pp. 1867–1868, Appendix, Spells, Spell #LVII. Title is Grimm's.

- ^ Bang (1901–1902), p. 4,

- ^ Bang's Norse hexeformulaer collection lacks commentary, but Bang (1884) makes clear he subscribes to the parallelism view espoused by Grimm and Bugge.

- ^ a b Fet, Jostein (2010). "Magiske Fromlar frå Hornindalen". Mal og Minne. 2: 134–155. (pdf)

- ^ Aasen, Ivar Andreas (1850). Ordbog over det norske folkesprog. Trykt hos C. C. Werner. p. 47.

- ^ Masser (1972), pp. 19–20

- ^ Grimm (1844), repr. Grimm (1865), pp. 1–29, vol.2

- ^ Grimm#LVII and Bang's no.4 have spelling differences, but both cite Hammond as source, and the identity is mentioned in Bang (1884), p. 170

- ^ Wadstein (1939)

- ^ Bang (1884), p. 170

- ^ Bang, Anton Christia (1884). Gjengangere fra hedenskabet og katholicismen blandt vort folk efter reformationen. Oslo: Mallingske. pp. 167–.

- ^ Stanley (1975), p. 78, citing Grimm's DM 1st ed., Anhang, p.cxlviii and, Grimm (1844), pp. 21–22.

- ^ Collected by Martin Bjørndal in Møre (Norway); printed in Bjørndal, Martin (1949). Segn og tru: folkeminne fra Møre. Oslo: Norsk Folkeminnelag. pp. 98–99. (cited by Kvideland & Sehmsdorf (2010), p. 141)

- ^ a b Kvideland & Sehmsdorf (2010), p. 141.

- ^ Rydberg, Viktor (1889). Undersökningar i Germanisk Mythologi. Vol. 2. A. Bonnier. p. 238.

- ^ a b Studier over de nordiske Gude- and Helte-sagns Oprindelse Bugge (1889), pp.287, 549- (addendum to p.284ff); Germ. tr. by Brenner, Bugge (1889b), p. 306

- ^ Carl Ohlson Arcadius, Om Bohusläns införlifvande med Sverige (1883), p.118

- ^ Kock, Axel (1887). "Var Balder äfven en tysk gud ?". Svenska Landsmål och Svenskt Folkliv. 6: cl (xlvii-cl).

- ^ a b Rydberg 1889, p. 239, volume 2

- ^ Nordlander, J. (1883). "Trollformler ock signerier (Smärre Meddelanden Nr. 2)". Svenska Landsmål och Svenskt Folkliv. 2: xlvii.

- ^ Ebermann (1903), p. 2

- ^ Kuhn, Adalbert (1864). "Indische und germanische segensprüche". Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung auf dem Gebiete der indogermanischen Sprachen. 13: 49–73 [52].

- ^ Thiele, Just Mathias (1860). Den Danske almues overtroiske meninger. Danmarks folkesagn. Vol. 3. Kjöbenhavn: C. A. Reitzel. pp. 124–125.

- ^ a b Chambers, William (1842). Popular Rhymes, Fireside Stories, and Amusements of Scotland. William and Robert Chambers. p. 37. (Grimm's cited source)

- ^ a b The New Statistical Account of Scotland. Vol. 15. Edinburgh; London: W. Blackwood and Sons for the Society for the Benefit of the Sons and Daughters of the Clergy. 1845. p. 141. (Originally issued in 52 numbers, beginning in March 1834) (Chamber's source)

- ^ Macbain1892b, p. 230

- ^ a b Macbain 1892a, p. 119, Macbain 1892b, pp. 223–4

- ^ Macbain, continued serialization of the article in Highland Society IV (1892-3), p.431 and Transactions 18 (1891-2), p.181

- ^ Macbain1892b, pp. 246–7

- ^ a b Kuhn 1864, p. 58

- ^ Cebrián, Reyes Bertolín (2006). Singing the Dead: A Model for Epic Evolution. Peter Lang. pp. 17–18. ISBN 9780820481654., quote: "The parallels of the Merserburger Charm in Vedic literature", is followed by the text of the Atharvaveda 4,12 and translation by Whitney (1905).

- ^ Wilhelm, Friedrich (1961). "The German Response to Indian Culture". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 81 (4–2): 395–405. doi:10.2307/595685. JSTOR 595685., "one of the 'Merseburger Zauberspruche' (Merseburg Spells) which has its parallel in the Atharvaveda"

- ^ Eichner, Heiner (2000–2001). "Kurze indo-germanische Betrachtungen über die atharvavedische Parallele zum Zweiten Merseburger Zauberspruch (mit Neubehandlung von AVS. IV 12)". Die Sprache. 42 (1–2): 214.

- ^ Atharva-Veda saṃhitā. First Half (Books I to VII). Translated by Whitney, William Dwight. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University. 1905. pp. 166–168. (also "Hymn IV, 12" in Whitney tr., Atharva-Veda Samhita. – via Wikisource.)

- ^ Lincoln 1986, p. 104.

- ^ Ködderitzsch, Rolf (1974). "Der Zweite Merseburger Zauberspruch und seine Parallelen". Zeitschrift für celtische Philologie. 33 (1): 45–57. doi:10.1515/zcph.1974.33.1.45. S2CID 162644696.

- ^ Tilak, Shrinivas (1989). Religion and Aging in the Indian Tradition. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780791400449.

- ^ Lincoln 1986, p. 104

References

edit- Editions

- Beck, Wolfgang (2011) [2003]. Die Merseburger Zaubersprüche (in German) (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden: Reichert. ISBN 978-3-89500-300-4.

- Braune, Wilhelm; Helm, Karl; Ebbinghaus, Ernst A., eds. (1994). Althochdeutsches Lesebuch: Zusammengestellt und mit Wörterbuch versehen (17th ed.). Tübingen: M. Niemeyer. pp. 89, 173–4. ISBN 3-484-10707-3.

- ———, ed. (1921). Althochdeutsches Lesebuch: Zusammengestellt und mit Wörterbuch versehen (8th ed.). Halle: Niemeyer. p. 85.

- Steinmeyer, Elias von (1916). Die kleineren althochdeutschen Sprachdenkmäler. Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung. pp. 365–367.

- The Merseburg Charms

- Beck, Wolfgang (2021). Die Merseburger Zaubersprüche: Eine Einführung (in German) (3rd ed.).

- Bostock, J. Knight (1976). King, K.C.; McLintock, D. R. (eds.). A Handbook on Old High German Literature (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 26–42. ISBN 0-19-815392-9.

- Giangrosso, Patricia (2016). "Charms". In Jeep, John M. (ed.). Medieval Germany: An Encyclopedia. Abingdon, New York: Routledge. pp. 111–114. ISBN 9781138062658.

- Grimm, Jacob (1844). "Über zwei entdeckte Gedichte aus der Zeit des deutschen Heidenthums". Philologische und historische Abhandlungen der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. Aus dem Jahre 1842: 21–2.

- ——— (1865). 'Kleinere Schriften. Vol. 2. Berlin: Harrwitz und Gossman. pp. 1–29. (reprint)

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0.

- Masser, Achim (1972). "Zum Zweiten Merseburger zauberspruch". Beiträge zur Geschichte der deutschen Sprache und Literatur. 18 (94). Hamnia: 19–25. doi:10.1515/bgsl.1972.1972.94.19. ISSN 1865-9373. S2CID 161280543.

- Schumacher, Meinolf (2000). "Geschichtenerzählzauber: Die Merseburger Zaubersprüche und die Funktion der historiola im magischen Ritual". In Zymner, Rüdiger (ed.). Erzählte Welt – Welt des Erzählens. Cologne: edition chōra. pp. 201–215. ISBN 3-934977-01-4.

- Steinhoff HH (1986). "Merseburger Zaubersprüche". In Ruh K, Keil G, Schröder W (eds.). Die deutsche Literatur des Mittelalters. Verfasserlexikon. Vol. 6. Berlin, New York: Walter De Gruyter. pp. 410–418. ISBN 978-3-11-022248-7.

- Stone, Alby (1993). "The second Merseburg Charm". Talking Stick (11).

- Wadstein, Elis (1939). "Zum zweiten merseburger zauberspruch". Studia Neophilologica. 12 (2): 205–209. doi:10.1080/00393273908586847.

- General

- Bang, Anton Christia, ed. (1901–1902). Norske hexeformularer og magiske opskrifter. Videnskabsselskabets skrifter: Historisk-filosofiske klasse, No.1. Kristiania (Oslo, Norway): I Commission hos Jacob Dybwad.

- Bugge, Sophus (1889). Studier over de nordiske Gude- and Helte-sagns Oprindelse. Albert Cammermeyer., p. 287, 549- (addendum to p. 284ff)

- ——— (1889b). Studien uber die Entstehung der nordischen Gotter und Heldensagen. Translated by Oscar Brenner. Berlin: C. Kaiser. p. 306.

- Ebermann, Oskar (1903). Blut- und Wundsegen in ihrer Entwicklung dargestellt. Palaestra:Untersuchungen und Texte aus der deutscehen und englischen Philologie. Vol. XXIV. Berlin: Mayer & Müller.

- Griffiths, Bill (2003). Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Magic (3rd revised edition). Anglo-Saxon Book. ISBN 978-1-898281-33-7.

- ———. "List Poems in Old English". Pores 3. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- Grimm, Jacob (1878). Deutsche Mythologie (4te Ausgabe). Vol. 3. Herrwitz & Gossmann. pp. 363–376, 492–508. (in: "Cap. XXXVIII. Sprüche und Segen"; "Beschwörungen")

- ——— (1884). "Chapter XXXVIII, Spells and Charms". Teutonic mythology. Vol. 3. Translated by Stallybrass, James Steven. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen.

- ——— (1888). Teutonic mythology. Vol. 4. Translated by Stallybrass, James Steven. W. Swan Sonnenschein & Allen.

- Hoptman, Ari (1999). "The Second Merseburg Charm: A Bibliographic Survey." Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics and Semiotic Analysis 4: 83–154.

- Kvideland, Reimund; Sehmsdorf, Henning K., eds. (2010). Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816619672.

- Lincoln, Bruce (1986). Myth, cosmos, and society: Indo-European themes of creation and destruction. Harvard University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780674597754.

- Macbain, Alexander (1892a). "Incantations and Magic Rhymes". The Highland Monthly. 3. Inverness: Northern Chronicle Office: 117–125.

- Cont. in: The Highland Monthly 4 (1892-3), pp. 227–444

- ——— (1892b). "Gaelic Incantation". Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness. 17: 224.

- Cont. in: Transactions 18 (1891-2), pp. 97–182

- Nicolson, William (1892). Myth and religion, or, An enquiry into their nature and relations. Press of the Finnish Literary Society. pp. 120–. ISBN 9780837098913. (discusses Rydberg and Bugge's commentary)

- Stanley, Eric Gerald (1975). The Search for Anglo-Saxon Paganism. ISBN 9780874716146.

- ——— (2000). Imagining the Anglo-Saxon Past. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0859915885. (Reprint)

- (Revised version; containing Stanley (1975), The Search for Anglo-Saxon Paganism and his Anglo-Saxon Trial by Jury (2000))

- Thorpe, Benjamin (1851). Northern Mythology: Comprising the Principal Popular Traditions and Superstiotions of Scandinavia, North Germany, and the Netherlands. Vol. 1. London: Edward Lumley. ISBN 9780524024379.