The American woodcock (Scolopax minor), sometimes colloquially referred to as the timberdoodle, mudbat, bogsucker, night partridge, or Labrador twister[2][3] is a small shorebird species found primarily in the eastern half of North America. Woodcocks spend most of their time on the ground in brushy, young-forest habitats, where the birds' brown, black, and gray plumage provides excellent camouflage.

| American woodcock | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Scolopacidae |

| Genus: | Scolopax |

| Species: | S. minor

|

| Binomial name | |

| Scolopax minor Gmelin, JF, 1789

| |

| |

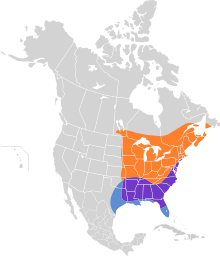

Breeding Year-round Nonbreeding

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The American woodcock is the only species of woodcock inhabiting North America.[4] Although classified with the sandpipers and shorebirds in the family Scolopacidae, the American woodcock lives mainly in upland settings. Its many folk names include timberdoodle, bogsucker, night partridge, brush snipe, hokumpoke, and becasse.[5]

The population of the American woodcock has fallen by an average of slightly more than 1% annually since the 1960s. Most authorities attribute this decline to a loss of habitat caused by forest maturation and urban development. Because of the male woodcock's unique, beautiful courtship flights, the bird is welcomed as a harbinger of spring in northern areas. It is also a popular game bird, with about 540,000 killed annually by some 133,000 hunters in the United States.[6]

In 2008, wildlife biologists and conservationists released an American woodcock conservation plan presenting figures for the acreage of early successional habitat that must be created and maintained in the United States and Canada to stabilize the woodcock population at current levels, and to return it to 1970s densities.[7]

Description

editThe American woodcock has a plump body, short legs, a large, rounded head, and a long, straight prehensile bill. Adults are 10 to 12 inches (25 to 30 cm) long and weigh 5 to 8 ounces (140 to 230 g).[8] Females are considerably larger than males.[9] The bill is 2.5 to 2.8 inches (6.4 to 7.1 cm) long.[5] Wingspans range from 16.5 to 18.9 inches (42 to 48 cm).[10]

The plumage is a cryptic mix of different shades of browns, grays, and black. The chest and sides vary from yellowish-white to rich tans.[9] The nape of the head is black, with three or four crossbars of deep buff or rufous.[5] The feet and toes, which are small and weak, are brownish gray to reddish brown.[9] Woodcocks have large eyes located high in their heads, and their visual field is probably the largest of any bird, 360° in the horizontal plane and 180° in the vertical plane.[11]

The woodcock uses its long, prehensile bill to probe in the soil for food, mainly invertebrates and especially earthworms. A unique bone-and-muscle arrangement lets the bird open and close the tip of its upper bill, or mandible, while it is sunk in the ground. Both the underside of the upper mandible and the long tongue are rough-surfaced for grasping slippery prey.[5]

Taxonomy

editThe genus Scolopax was introduced in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[12] The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock.[13] The type species is the Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola).[14]

Distribution and habitat

editWoodcocks inhabit forested and mixed forest-agricultural-urban areas east of the 98th meridian. Woodcocks have been sighted as far north as York Factory, Manitoba, and east to Labrador and Newfoundland. In winter, they migrate as far south as the Gulf Coast of the United States and Mexico.[9]

The primary breeding range extends from Atlantic Canada (Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick) west to southeastern Manitoba, and south to northern Virginia, western North Carolina, Kentucky, northern Tennessee, northern Illinois, Missouri, and eastern Kansas. A limited number breed as far south as Florida and Texas. The species may be expanding its distribution northward and westward.[9]

After migrating south in autumn, most woodcocks spend the winter in the Gulf Coast and southeastern Atlantic Coast states. Some may remain as far north as southern Maryland, eastern Virginia, and southern New Jersey. The core of the wintering range centers on Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia.[9] Based on the Christmas Bird Count results, winter concentrations are highest in the northern half of Alabama.

American woodcocks live in wet thickets, moist woods, and brushy swamps.[4] Ideal habitats feature early successional habitat and abandoned farmland mixed with forest. In late summer, some woodcocks roost on the ground at night in large openings among sparse, patchy vegetation.[9]

- Courtship/breeding habitats include forest openings, roadsides, pastures, and old fields from which males call and launch courtship flights in springtime.

- Nesting habitats include thickets, shrubland, and young to middle-aged forest interspersed with openings.

- Feeding habitats have moist soil and feature densely growing young trees such as aspen (Populus spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and mixed hardwoods less than 20 years of age, and shrubs, particularly alder (Alnus spp.).

- Roosting habitats are semiopen sites with short, sparse plant cover, such as blueberry barrens, pastures, and recently heavily logged forest stands.[9]

Migration

editWoodcocks migrate at night. They fly at low altitudes, individually or in small, loose flocks. Flight speeds of migrating birds have been clocked at 16 to 28 mi/h (26 to 45 km/h). However, the slowest flight speed ever recorded for a bird, 5 mi/h (8 km/h), was recorded for this species.[15] Woodcocks are thought to orient visually using major physiographic features such as coastlines and broad river valleys.[9] Both the autumn and spring migrations are leisurely compared with the swift, direct migrations of many passerine birds.

In the north, woodcocks begin to shift southward before ice and snow seal off their ground-based food supply. Cold fronts may prompt heavy southerly flights in autumn. Most woodcocks start to migrate in October, with the major push from mid-October to early November.[16] Most individuals arrive on the wintering range by mid-December. The birds head north again in February. Most have returned to the northern breeding range by mid-March to mid-April.[9]

Migrating birds' arrival at and departure from the breeding range is highly irregular. In Ohio, for example, the earliest birds are seen in February, but the bulk of the population does not arrive until March and April. Birds start to leave for winter by September, but some remain until mid-November.[17]

Behavior and ecology

editFood and feeding

editWoodcocks eat mainly invertebrates, particularly earthworms (Oligochaeta). They do most of their feeding in places where the soil is moist. They forage by probing in soft soil in thickets, where they usually remain well-hidden. Other items in their diet include insect larvae, snails, centipedes, millipedes, spiders, snipe flies, beetles, and ants. A small amount of plant food is eaten, mainly seeds.[9] Woodcocks are crepuscular, being most active at dawn and dusk.

Breeding

editIn spring, males occupy individual singing grounds, openings near brushy cover from which they call and perform display flights at dawn and dusk, and if the light levels are high enough, on moonlit nights. The male's ground call is a short, buzzy peent. After sounding a series of ground calls, the male takes off and flies from 50 to 100 yd (46 to 91 m) into the air. He descends, zigzagging and banking while singing a liquid, chirping song.[9] This high spiralling flight produces a melodious twittering sound as air rushes through the male's outer primary wing feathers.[18]

Males may continue with their courtship flights for as many as four months running, sometimes continuing even after females have already hatched their broods and left the nest. Females, known as hens, are attracted to the males' displays. A hen will fly in and land on the ground near a singing male. The male courts the female by walking stiff-legged and with his wings stretched vertically, and by bobbing and bowing. A male may mate with several females. The male woodcock plays no role in selecting a nest site, incubating eggs, or rearing young. In the primary northern breeding range, the woodcock may be the earliest ground-nesting species to breed.[9]

The hen makes a shallow, rudimentary nest on the ground in the leaf and twig litter, in brushy or young-forest cover usually within 150 yd (140 m) of a singing ground.[5] Most hens lay four eggs, sometimes one to three. Incubation takes 20 to 22 days.[4] The down-covered young are precocial and leave the nest within a few hours of hatching.[9] The female broods her young and feeds them. When threatened, the fledglings usually take cover and remain motionless, attempting to escape detection by relying on their cryptic coloration. Some observers suggest that frightened young may cling to the body of their mother, that will then take wing and carry the young to safety.[19] Woodcock fledglings begin probing for worms on their own a few days after hatching. They develop quickly and can make short flights after two weeks, can fly fairly well at three weeks, and are independent after about five weeks.[4]

The maximum lifespan of adult American woodcock in the wild is 8 years.[20]

Rocking behavior

editAmerican woodcocks occasionally perform a rocking behavior where they will walk slowly while rhythmically rocking their bodies back and forth. This behavior occurs during foraging, leading ornithologists such as Arthur Cleveland Bent and B. H. Christy to theorize that this is a method of coaxing invertebrates such as earthworms closer to the surface.[21] The foraging theory is the most common explanation of the behavior, and it is often cited in field guides.[22] This theory is complicated by observations of rocking while slowly walking across ground that cannot be foraged, such as hard roads or deep snow.[23]

An alternative theory for the rocking behavior has been proposed by some biologists, such as Bernd Heinrich. It is thought that this behavior is a display to indicate to potential predators that the bird is aware of them.[24] Heinrich notes that some field observations have shown that woodcocks will occasionally flash their tail feathers while rocking, drawing attention to themselves. This theory is supported by research done by John Alcock who believes this is a type of aposematism.[25]

Population status

editHow many woodcock were present in eastern North America before European settlement is unknown. Colonial agriculture, with its patchwork of family farms and open-range livestock grazing, probably supported healthy woodcock populations.[5]

The woodcock population remained high during the early and mid-20th century, after many family farms were abandoned as people moved to urban areas, and crop fields and pastures grew up in brush. In recent decades, those formerly brushy acres have become middle-aged and older forest, where woodcock rarely venture, or they have been covered with buildings and other human developments. Because its population has been declining, the American woodcock is considered a "species of greatest conservation need" in many states, triggering research and habitat-creation efforts in an attempt to boost woodcock populations.

Population trends have been measured through springtime breeding bird surveys, and in the northern breeding range, springtime singing-ground surveys.[9] Data suggest that the woodcock population has fallen rangewide by an average of 1.1% yearly over the last four decades.[7]

Conservation

editThe American woodcock is not considered globally threatened by the IUCN. It is more tolerant of deforestation than other woodcocks and snipes; as long as some sheltered woodland remains for breeding, it can thrive even in regions that are mainly used for agriculture.[1][26] The estimated population is 5 million, so it is the most common sandpiper in North America.[18]

The American Woodcock Conservation Plan presents regional action plans linked to bird conservation regions, fundamental biological units recognized by the U.S. North American Bird Conservation Initiative. The Wildlife Management Institute oversees regional habitat initiatives intended to boost the American woodcock's population by protecting, renewing, and creating habitat throughout the species' range.[7]

Creating young-forest habitat for American woodcocks helps more than 50 other species of wildlife that need early successional habitat during part or all of their lifecycles. These include relatively common animals such as white-tailed deer, snowshoe hare, moose, bobcat, wild turkey, and ruffed grouse, and animals whose populations have also declined in recent decades, such as the golden-winged warbler, whip-poor-will, willow flycatcher, indigo bunting, and New England cottontail.[27]

Leslie Glasgow,[28] the assistant secretary of the Interior for Fish, Wildlife, Parks, and Marine Resources from 1969 to 1970, wrote a dissertation through Texas A&M University on the woodcock, with research based on his observations through the Louisiana State University (LSU) Agricultural Experiment Station. He was an LSU professor from 1948 to 1980 and an authority on wildlife in the wetlands.[29]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2020). "Scolopax minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693072A182648054. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693072A182648054.en. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ The American Woodcock Today | Woodcock population and young forest habitat management. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

- ^ 10 Fun Facts About The American Woodcock. audubon.org.

- ^ a b c d Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Houghton Mifflin, pp. 225–226, ISBN 0618159886.

- ^ a b c d e f Sheldon, William G. (1971). Book of the American Woodcock. University of Massachusetts.

- ^ Cooper, T. R. & K. Parker (2009). American woodcock population status, 2009. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Laurel, Maryland.

- ^ a b c Kelley, James; Williamson, Scot & Cooper, Thomas, eds. (2008). American Woodcock Conservation Plan: A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America.

- ^ Smith, Christopher (2000). Field Guide to Upland Birds and Waterfowl. Wilderness Adventures Press, pp. 28–29, ISBN 1885106203.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Keppie, D. M. & R. M. Whiting Jr. (1994). American Woodcock (Scolopax minor), The Birds of North America.

- ^ "American Woodcock Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Jones, Michael P.; Pierce, Kenneth E.; Ward, Daniel (2007). "Avian vision: a review of form and function with special consideration to birds of prey". Journal of Exotic Pet Medicine. 16 (2): 69. doi:10.1053/j.jepm.2007.03.012.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 145.

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 351. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Peters, James Lee, ed. (1934). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 278.

- ^ Amazing Bird Records. Trails.com (2010-07-27). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

- ^ Sepik, G. F. and E. L. Derleth (1993). Habitat use, home range size, and patterns of moves of the American Woodcock in Maine. in Proc. Eighth Woodcock Symp. (Longcore, J. R. and G. F. Sepik, eds.) Biol. Rep. 16, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C.

- ^ Ohio Ornithological Society (2004). Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b O'Brien, Michael; Crossley, Richard & Karlson, Kevin (2006). The Shorebird Guide. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, pp. 444–445, ISBN 0618432949.

- ^ Mann, Clive F. (1991). "Sunda Frogmouth Batrachostomus cornutus carrying its young" (PDF). Forktail. 6: 77–78. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 28, 2008.

- ^ Wasser, D. E.; Sherman, P. W. (2010). "Avian longevities and their interpretation under evolutionary theories of senescence". Journal of Zoology. 280 (2): 103. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2009.00671.x.

- ^ Bent, A. C. (1927). "Life histories of familiar North American birds: American Woodcock, Scalopax minor". United States National Museum Bulletin. 142 (1). Smithsonian Institution: 61–78.

- ^ "American Woodcock". Audubon. National Audubon Society. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ Marshall, William H. (October 1, 1982). "Does the Woodcock Bob or Rock: and Why?". The Auk. 99 (4): 791–792 – via Oxford Academic.

- ^ Heinrich, Bernd (March 1, 2016). "Note on the Woodcock Rocking Display". Northeastern Naturalist. 23 (1): N4–N7. doi:10.1656/045.023.0109. S2CID 87482420.

- ^ Alcock, John (2013). Animal behavior: an evolutionary approach (10th ed.). Sunderland (Mass.): Sinauer. p. 522. ISBN 978-0878939664.

- ^ Henninger, W. F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

- ^ the Woodcock Management Plan. Timberdoodle.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

- ^ "Leslie L. Glasgow". January 13, 2017.

- ^ Paul Y. Burns (June 13, 2008). "Leslie L. Glasgow". lsuagcdenter.com. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

Further reading

edit- Choiniere, Joe (2006). Seasons of the Woodcock: The secret life of a woodland shorebird. Sanctuary 45(4): 3–5.

- Sepik, Greg F.; Owen, Roy & Coulter, Malcolm (1981). A Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast, Misc. Report 253, Maine Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Maine.

External links

edit- American woodcock species account – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- American Woodcock – Scolopax minor – USGS Patuxent Bird Identification Infocenter

- American Woodcock Bird Sound

- Rite of Spring – Illustrated account of the phenomenal courtship flight of the male American woodcock

- American Woodcock - Scolopax minor, Internet Bird Collection / Macaulay Library

- Photo-High Res; Article – www.fws.gov–"Moosehorn National Wildlife Refuge", photo gallery and analysis

- American Woodcock Conservation Plan A Summary of and Recommendations for Woodcock Conservation in North America

- Timberdoodle.org: the Woodcock Management Plan

- Sepik, Greg F.; Ray B. Owen Jr.; Malcolm W. Coulter (July 1981). "Landowner's Guide to Woodcock Management in the Northeast". Maine Agricultural Experiment Station Miscellaneous Report 253.