Paris green (copper(II) acetate triarsenite or copper(II) acetoarsenite) is an arsenic-based organic pigment. As a green pigment it is also known as Mitis green, Schweinfurt green, Sattler green, emerald, Vienna green, Emperor green or Mountain green. It is a highly toxic emerald-green crystalline powder[4] that has been used as a rodenticide and insecticide,[5] and also as a pigment.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

C.I. pigment green 21, emerald green, Schweinfurt green, imperial green, Vienna green, Mitis green, Veronese green[1]

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.242 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1585 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

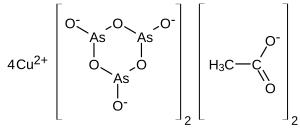

| Cu(C2H3O2)2·3Cu(AsO2)2 | |

| Molar mass | 1013.79444 g/mol |

| Appearance | Emerald green crystalline powder |

| Density | >1.1 g/cm3 (20 °C) |

| Melting point | > 345 °C (653 °F; 618 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| insoluble | |

| Solubility | soluble but unstable in acids insoluble in alcohol |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H302, H410 | |

| P260, P264, P273, P280, P301+P312, P301+P330+P331, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P362, P391, P405, P501 | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

22 mg/kg |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

[1910.1018] TWA 0.010 mg/m3[2] |

REL (Recommended)

|

Ca C 0.002 mg/m3 [15-minute][2] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

Ca [5 mg/m3 (as As)][2] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | CAMEO MSDS |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

| Paris green | |

|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #50C878 |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (80, 200, 120) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (140°, 60%, 78%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (72, 71, 137°) |

| Source | Maerz and Paul[3] |

| ISCC–NBS descriptor | Vivid yellowish green |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |

It was manufactured in 1814 to be a pigment to make a vibrant green paint, and was used by many notable painters in the 19th century. The color of Paris green is said to range from a pale blue green when very finely ground, to a deeper green when coarsely ground. Due to the presence of arsenic, the pigment is extremely toxic. In paintings, the color can degrade quickly.

Preparation and structure

editParis green may be prepared by combining copper(II) acetate and arsenic trioxide.[6] The structure was confirmed by X-ray crystallography.[7]

History

editIn 1814, Paris green was invented by paint manufacturers Wilhelm Sattler and Friedrich Russ, in Schweinfurt, Germany for the Wilhelm Dye and White Lead Company. They were attempting to produce a more stable pigment than Scheele's green, seeking to make a green that was less susceptible to darkening around sulfides.[i] In 1822, the recipe for emerald green was published by Justus von Liebig and André Braconnot.[8]

In 1867, the pigment was named Paris green and was officially recognized as the first chemical insecticide in the world. Because of its arsenic content, the pigment was dangerous and toxic to manufacture, often resulting in factory poisonings.[9][10] At the time, emerald green was praised as a more durable and vibrant substitute for Scheele's green, even though it would later prove to degrade quickly and react with other manufactured paints.[citation needed]

Pigment

editIn paintings, the pigment produces a rich, dark green with an undertone of blue. In comparison, Scheele's green is more yellow, and therefore, more lime-green.[11]: 220 Paris green became popular in the 19th century because of its brilliant color.[11]: 223 It was also called emerald green because of its resemblance to the gemstone's deep color.

Permanence

editThe pigment has a tendency to darken and turn brown. The issue was already apparent in the 19th century. In a 1888 study, watercolors with the pigment were shown to darken and turn brown when exposed to natural light and air. Experiments at the turn of the 20th century gave mixed results. Some found that the Paris green degraded slightly while other sources said the pigment was weatherproof.[11]: 227 This discrepancy could be due to the fact that each experiment used a different brand of Paris green.[11]: 228

Paris green in Descente des Vaches by Théodore Rousseau has changed significantly.[12]

Related pigments

editSimilar natural compounds are the minerals chalcophyllite Cu

18Al

2(AsO

4)

3(SO

4)

3(OH)

27·36H

2O, conichalcite CaCu(AsO

4)(OH), cornubite Cu

5(AsO

4)

2(OH)

4·H

2O, cornwallite Cu

5(AsO

4)

2(OH)

4·H

2O, and liroconite Cu

2Al(AsO

4)(OH)

4·4H

2O. These minerals range in color from greenish blue to slightly yellowish green.[citation needed]

Scheele's green is a chemically simpler, less brilliant, and less permanent, copper-arsenic pigment used for a rather short time before Paris green was first prepared, which was approximately 1814. It was popular as a wallpaper pigment and would degrade, with moisture and molds, to arsine gas. Paris green was used in wallpaper to some extent and may have degraded similarly.[13] Both pigments were once used in printing ink formulations.[citation needed]

The ancient Romans used one of them, possibly conichalcite, as a green pigment. The Paris green paint used by the Impressionists is said to have been composed of relatively coarse particles. Later, the chemical was produced with increasingly small grinds and without carefully removing impurities. Its permanence suffered. It is likely that it was ground more finely for use in watercolors and inks.[citation needed]

Uses

editPainting

editParis green was widely used by 19th-century artists. It is present in several paintings by Claude Monet and Paul Gauguin, who found its color difficult to replicate with natural materials.[11]: 256 [14]

Insecticide

editIn 1867, farmers in Illinois and Indiana found that Paris green was effective against the Colorado potato beetle, an aggressive agricultural pest. Despite concerns regarding the safety of using arsenic compounds on food crops, Paris green became the preferred method for controlling the beetle. By the 1880s, Paris green had become the first widespread use of a chemical insecticide in the world.[16] It was also used widely in the Americas to control the tobacco budworm, Heliothis virescens.[17] To kill codling moth, it was mixed with lime and sprayed on fruit trees.[18]

Paris green was heavily sprayed by airplane in Italy, Sardinia, and Corsica during 1944 and in Italy in 1945 to control malaria.[19] It was once used to kill rats in Parisian sewers, which is how it acquired its common name.[20]

However, the manufacturing of the insecticide caused many health complications for factory workers, and in certain cases was lethal.[21]

-

Mixing "Paris green" and road dust preparatory to dusting streams and breeding places of mosquitoes during World War II

-

Use as insecticide, poster issued by US Public Health Service

Bookbindings

editThroughout the 19th century, Paris green and similar arsenic pigments were used in books, particularly on bookcloth coverings, textblock edges, decorative labels and onlays, and in printed or manual illustrations. The colorant is particularly prevalent in bookbindings from the 1850s and 1860s published in Germany, England, France, and the United States. Use of arsenic-containing pigments waned in the later part of the 19th-century with heightened awareness of their toxicity and the availability of less toxic chromium- and cobalt-based alternatives. Since February 2024, several German libraries have started to block public access to their stock of 19th century books, to check for the degree of poisoning.[22][23][24][25][26][27] The Poison Book Project has cataloged books with these bindings.

Wallpaper

editParis green became a popular paint in mass-produced wallpaper, which is believed to have shortened lifespans.[28] Wallpaper swatches from this era have been preserved in the book Shadows from the Walls of Death.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Sulfur was commonly produced from burning coal fires.

- ^ "Health & Safety in the Arts -- Painting & Drawing Pigments". Environmental Management Division, City of Tucson AZ. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ a b c NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0038". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ The color displayed in the color box above matches the color called emerald green in the 1930 book by Maerz and Paul A Dictionary of Color New York:1930 McGraw-Hill; the color emerald green is displayed on page 75, Plate 26, Color Sample J10.

- ^ "Hazardous Substance Fact Sheet" (PDF). NJ Dept. of Health and Senior Services. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ "Dangers in the Manufacture of Paris Green and Scheele's Green". Monthly Review of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. 5 (2): 78–83. 1917. JSTOR 41829377.

- ^ "H.Wayne Richardson, "Copper Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a07_567

- ^ Pertlik, F. (1977). "Die Kristallstruktur von Cu2As3O6CH3COO". Zeitschrift für Kristallographie. 145 (1–2): 35–45. Bibcode:1977ZK....145...35P. doi:10.1524/zkri.1977.145.1-2.35.

- ^ Zieske, Faith (1995). "An Investigation of Paul Cézanne's Watercolors With Emphasis on Emerald". The Book and Paper Group: Annual.

- ^ Haynes, William (1954). American Chemical Industry: Background and Beginnings (Vol. 1 ed.). D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc. pp. 355–369.

- ^ Emsley, John (2005). The Elements of Murder: A History of Poison. OUP. p. 118. ISBN 9780192805997.

- ^ a b c d e Fiedler, Inge; Bayard, Michael A. (2012). "Emerald Green and Scheele's Green". Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics. Vol. 3. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art. pp. 219–71.

- ^ Keune, Katrien; Boon, Jaap J.; Boitelle, R.; Shimazdu, Y. (July 2013). "Degradation of Emerald Green in Oil Paint and Its Contribution to the Rapid Change in Colour of the Descente Des Vaches (1834-1835)". Studies in Conservation. 58 (3): 199–210. doi:10.1179/2047058412Y.0000000063. JSTOR 42751821 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Zawacki, Alexander J. (23 January 2018). "How a Library Handles a Rare and Deadly Book of Wallpaper Samples". Atlas Obscura.

- ^ Mars, Ashley Grove (11 June 2020). "Chrysler Museum of Art |". Chrysler Museum of Art. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ Lipscher, Juraj. ""Georges Seurat, A Sunday on La Grande Jatte"". Colorlex.

- ^ Sorenson 1995

- ^ Blanco, Carlos (2012). "Heliothis virescens and Bt cotton in the United States". GM Crops & Food: Biotechnology in Agriculture and the Food Chain. 3 (3): 201–212. doi:10.4161/gmcr.21439. PMID 22892654.

- ^ https://www.newspapers.com/image/505098962/?match=1&terms=Lime Minister of Agriculture of the United States Gives Advice, Victoria Daily Times, March 27, 1895, p.2.

- ^ Justin M. Andrews, Sc. D. (1963). "Preventive Medicine in World War II, Chapter V. North Africa, Italy, and the Islands of the Mediterranean". Washington, D.C. USA: Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army. p. 281. Retrieved 30 September 2008.

- ^ The Natural Paint Book, by Lynn Edwards, Julia Lawless, Table of contents

- ^ Whorton, James C. (2010). The Arsenic Century: How Victorian Britain was Poisoned at Home, Work, and Play. OUP. p. 162. ISBN 9780191623431.

- ^ dbv-Kommission Bestandserhaltung (December 2023). "Information zum Umgang mit potentiell gesundheitsschädigenden Pigmentbestandteilen an historischen Bibliotheksbeständen (hier: arsenhaltige Pigmente)" (PDF). www.bibliotheksverband.de (in German). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024. (6 pages)

- ^ "Arsenbelastete Bücher" [Arsen contaminated books]. www.uni-bielefeld.de (in German). Universität Bielefeld. 2024. Archived from the original on 11 March 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ "Werke aus dem 19. Jahrhundert: Arsenverdacht – Unibibliothek überprüft 15.000 Bücher". www.spiegel.de (in German). 6 March 2024. Archived from the original on 17 March 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ dbv-Kommission Bestandserhaltung (29 February 2024). "Aktuelles: Information zum Umgang mit potentiell gesundheitsschädigenden Pigmentbestandteilen, wie arsenhaltigen Pigmenten, an historischen Bibliotheksbeständen". www.bibliotheksverband.de (in German). Retrieved 6 March 2024.

- ^ Pilz, Michael (4 March 2024). "Warum von grünen Büchern eine Gefahr ausgeht" [Why green books are dangerous]. Kultur > Arsen. Welt (in German). Archived from the original on 4 March 2024. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ University of Delaware. "Arsenic Bookbindings | Poison Book Project". Poison Book Project.

- ^ Bartrip, P. W. J. (1994). "How Green Was My Valance?: Environmental Arsenic Poisoning and the Victorian Domestic Ideal". The English Historical Review. 109 (433): 891–913. ISSN 0013-8266.

Further reading

edit- Fiedler, I. and Bayard, M. A., "Emerald Green and Scheele’s Green", in Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 3: E.W. Fitzhugh (Ed.) Oxford University Press 1997, pp. 219–271

- Hughes, Michael F.; et al. (2011). "Arsenic Exposure and Toxicology: A Historical Perspective". Toxicological Sciences. 123 (2): 305–332. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfr184. PMC 3179678. PMID 21750349.

- Sorensen, W. Conner (1995). Brethren of the Net, American Entomology, 1840-1880. University of Alabama Press. pp. 124–125.

- Spear, Robert J., The Great Gypsy Moth War, A History of the First Campaign in Massachusetts to Eradicate the Gypsy Moth, 1890–1901. University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst and Boston, 2005. ISBN 1-55849-479-0