The Savoy Palace, considered the grandest nobleman's townhouse of medieval London, was the residence of prince John of Gaunt until it was destroyed during rioting in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. The palace was on the site of an estate given to Peter II, Count of Savoy, in the mid-13th century, which in the following century came to be controlled by Gaunt's family and then the monarch by right of the Duchy of Lancaster. `It was situated between the Strand and the River Thames. French monarch John II of France died here during his "honourable captivity", after an illness. In the locality of the palace, the administration of law was by a special jurisdiction, separate from the rest of the county of Middlesex, known as the Liberty of the Savoy.

| Savoy Palace | |

|---|---|

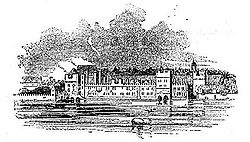

1848 engraving by Charles Thurston Thompson | |

| General information | |

| Type | townhouse |

| Architectural style | Norman |

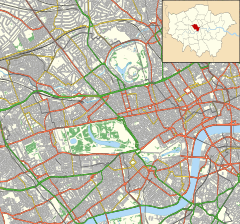

| Location | Liberty of the Savoy, Middlesex |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°30′38″N 0°7′13″W / 51.51056°N 0.12028°W |

| Named for | Peter II, Count of Savoy |

| Destroyed | 1381 |

| Owner | Peter II, Count of Savoy Edmund Crouchback Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster Henry of Grosmont, 1st Duke of Lancaster John of Gaunt |

| References | |

| https://www.duchyoflancaster.co.uk/properties-and-estates/the-urban-survey/ | |

The Tudor-era Savoy Chapel is located on the site of the former palace and has carried on the name. The name is also carried on by the Savoy Theatre and Savoy Hotel also located on the former estate.

Savoy Palace

editIn the Middle Ages, although there were many noble palaces within the walls of the City of London, the most desirable location for housing the nobility was the Strand, which was the greatest part of the ceremonial route between the City and the Palace of Westminster, where the business of Parliament and the royal court was transacted. Other advantages of the Strand were that a house could have a water frontage on the Thames, the great water highway, and be free of the stink, smoke, and social tumult of the City of London downstream and generally downwind to the east, and its constant threat of fires.

In 1246 King Henry III granted the land between the Strand and the Thames, on which the palace was soon built, to an uncle of Queen Eleanor, Peter, Count of Savoy, whom he created Feudal Baron of the Honour of Richmond. The house the Count of Savoy built there later became the home of Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, and his descendants, the Dukes of Lancaster, lived there throughout the next century. In the 14th century, when the Strand was paved as far as the Savoy, it was the vast riverside London residence of John of Gaunt, a younger son of King Edward III who had inherited by marriage the title and lands of the Dukes of Lancaster. He was the nation's power broker and in his time was the richest man in the kingdom second to the king. The Savoy was the most magnificent nobleman's house in England. It was famous for its owner's magnificent collection of tapestries, jewels, and other ornaments. Geoffrey Chaucer began writing The Canterbury Tales while working at the Savoy Palace as a clerk.[1]

Destruction

editDuring the Peasants' Revolt led by Wat Tyler in 1381, the rioters, who blamed John of Gaunt for the introduction of the poll tax that had precipitated the revolt, systematically demolished the Savoy and everything in it. What could not be smashed or burned was thrown into the river. Jewellery was pulverised with hammers, and it was said[citation needed] that one rioter found by his fellows to have kept a silver goblet for himself was killed for doing so. Despite this, the name Savoy was retained by the site.

Savoy Hospital

editIt was here that Henry VII founded the Savoy Hospital for poor, needy people, endowing it with land and leaving instructions for it in his will.[2] In 1512, letters patent issued by Henry's successor, Henry VIII, established the hospital as a body corporate consisting of a master and four chaplains, enabling it to acquire the land and begin building; the first office-holders appear to have been appointed in 1517.[3] The grand structure ('dedicated to the honour of the Blessed Jesus, the Virgin Mary, and St. John the Baptist')[3] was the most impressive hospital of its time in the country and the first to benefit from permanent medical staff. It consisted of a large cruciform arrangement of dormitories, around which were placed the chapel, separate lodgings for the master and other officials, domestic ranges and a tower, which served among other things as a secure treasury and archive.[3] Statutes published in 1523 stipulated a distinct role for each chaplain (namely seneschal, sacristan, confessor and hospitaller) and listed several other officials, including a matron, who was assisted by twelve other women. Each evening, an hour before sunset, the hospitaller, vice-matrons and others opened the gates and admitted the poor, who went first to the chapel to pray for the founder, then to the dormitory where they were allotted a bed for the night; the matron's staff were also to see that the men were bathed and their clothing washed. In the morning they departed (though the sick were allowed to remain and were attended to).[3]

From early in its existence the hospital appears to have been prone to mismanagement.[4] An inquiry into its administration was held in 1535. In 1553 the foundation was suppressed by King Edward VI, only to be refounded three years later by Queen Mary. In 1570 the master, Thomas Thurland, was removed for abuse of office,[3] after removing the hospital's treasures, selling its beds, burdening it with a private debt (of £2,500), and engaging in sexual relations with the staff.[4] Thereafter the hospital's fortunes waned. Buildings in the precincts were converted into houses for the nobility (and in the course of the 17th century several were given over to tradesmen). During the Civil War it was requisitioned to serve as a military hospital. When Charles II came to the throne, he re-established the hospital under its former statutes; however, in 1670 some of the buildings were again taken over by the military (for the use of men wounded in the Dutch Wars),[3] and in 1679 the Great Dormitory and the Sisters' Lodgings were converted into barracks for the Foot Guards.[5] By this time the nobility had vacated their houses within the precincts, and a number of tradespeople had moved in, including glove-makers, printers and leather-sellers. In 1695 a military prison was built on part of the site by Sir Christopher Wren.[4]

The Savoy Conference had been held here in 1661 between Anglican bishops and leading nonconformists, which had led indirectly to the establishment within the precincts of a variety of chapels for different nonconformist congregations. French Protestants were given use of the 'Little Chapel' at that time (it was rebuilt for them by Wren in 1685); the German Lutherans were given the former Sisters' Hall to serve as a church in 1694. A German Calvinist Chapel and a Quaker Meeting House were also provided on the site.[4]

A commission appointed by King William III reported that the hospital's main function, relief of the poor, was being utterly neglected; it made recommendations, but these were not enacted.[3] In 1702, the office of master being vacant, Sir Nathan Wright, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, dismissed the remaining chaplains and formally declared the hospital foundation dissolved.[3]

List of masters of the Savoy Hospital

editThe masters of the Savoy were:[3]

- 1517 William Hogill (occurs 1529 and 1541)

- 1551 Robert Bowes

- 1553 Ralph Jackson (reappointed 1556)[6]

- c. 1559 Thomas Thurland (occurs 1559 and 1561, deposed 1570)

- c. 1570 William Mount (died 1602)

- 1602 Richard Neile

- 1608 George Montaigne (appointed Bishop of Lincoln 1617)

- 1618 Walter Balcanquhall (appointed and resigned 1618)

- 1618 Marco Antonio de Dominis (resigned 1621)

- 1621 Walter Balcanquhall (deposed 1645)[7]

- 1629 John Wilson

- 1645 John Bond[7][8]

- 1658 William Hooke[9]

- 1660 Gilbert Sheldon (appointed Archbishop of Canterbury 1663)

- 1663 Henry Killigrew (died 1700)[10]

- 1700–1702 Vacant

Savoy Barracks

editThe Hospital complex remained in use as barracks for most of the 18th century. In 1776 much of the structure was destroyed in a fire; at the time it housed a military infirmary, prison and recruiting station. As early as 1775 Sir William Chambers (who was already responsible for rebuilding the adjacent riverside property, Somerset House, to serve as government offices) was asked to draw up plans to replace the Hospital buildings with an entirely new Barracks for the Foot Guards (to accommodate 3,000 men). He drew up plans for a three-sided quadrangle of six-storey buildings, open towards the river, behind an elevated river terrace (akin to that built as Somerset House): details included pyramid roofs on the four corner pavilions, a large double-domed structure in the centre of the north wing (which would have served as a chapel) and a subterranean gallery where prisoners would exercise, beneath the main parade ground. He was paid for his design in 1795 but the scheme never went ahead, being finally dropped in 1804.[11] In 1816–20 almost all the remaining hospital buildings were demolished to make way for the approach road to the new Waterloo Bridge.[4]

Savoy Chapel

editThe only hospital building to survive the 19th-century demolition was its hospital chapel, dedicated to St John the Baptist. It once hosted a German Lutheran congregation, and is now again in Church of England use as the church for the Duchy of Lancaster and Royal Victorian Order. Before taking up folk music, the young Martin Carthy was a chorister here.

Modern London

editThe Savoy Palace and Hospital are remembered in the names of the Savoy Hotel and the Savoy Theatre which now stand on the site. Many of the nearby streets are also named for the Savoy: Savoy Buildings, Court, Hill, Place, Row, Street and Way. Savoy Place is the London headquarters of the Institution of Engineering and Technology.

The Savoy Estate is owned by the Duchy of Lancaster, held in trust for the Sovereign in His or Her role as Duke of Lancaster.[12]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Richard D'Oyly Carte" Archived 2009-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, Lyric Opera San Diego website

- ^ "VCH: "Hospital of the Savoy"". British-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Hospitals – Hospital of the Savoy | A History of the County of London: Volume 1 (pp. 546–549)". British-history.ac.uk. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Savoy Palace" in Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert (1983) The London Encyclopaedia

- ^ Osborne, Mike (2012). Defending London: A Military History from Conquest to Cold War. Stroud, Gloucs.: The History Press.

- ^ Loftie, William John (1878). Memorials of the Savoy. London: Macmillan and Co. pp. 110–114. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ a b Journals of the House of Lords. Vol. 8. 1645. p. 81. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- ^ Wright, Stephen. "Bond, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2826. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Moore, Susan Hardman. "Hooke, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13688. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Aitken, George Atherton (1892). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 31. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Harris, John; Snodin, Michael (1996). Sir William Chambers: Architect to George III. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 123.

- ^ "The Urban Survey - Duchy of Lancaster". duchyoflancaster.co.uk.

Further reading

edit- Cowie, L. W. "The Savoy – Palace and Hospital" History Today (March 1974), Vol. 24 Issue 3, pp 173–179 online.

- Marshall, John (2023). Peter of Savoy: The Little Charlemagne. Pen and Sword.

- Stanford, Charlotte (2015). The Building Accounts of the Savoy Hospital, London, 1512–1520. Rochester, NY: Boydell. p. 456. ISBN 978-1-78327-066-8.