San Salvador Huixcolotla is a town and municipality in the Mexican state of Puebla in southeastern Mexico that may be best known as the birthplace of papel picado.[6][7] San Salvador is of Spanish origin and translates to "Holy Savior" and Huixcolotla is Nahuatl for "place of the curved spines".[8]

San Salvador Huixcolotla | |

|---|---|

Municipality[1] and town | |

Parroquia del Divino Salvador (Church of the Divine Savior) in the center of San Salvador Huixcolotla | |

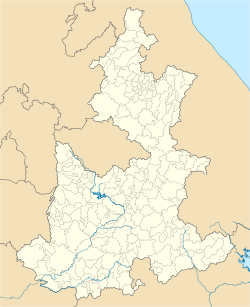

Location of Puebla State in Mexico | |

| Coordinates: 18°54′53″N 97°46′25″W / 18.91472°N 97.77361°W[2] | |

| Country | |

| State | Puebla |

| Government | |

| • Presidente | C. Silvano Teodoro Mauricio (2018-2021)[3] ( |

| Area | |

| • Total | 23.909 km2 (9.231 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,040 m (6,690 ft) |

| Population (2010)[5] | |

| • Total | 12,148 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central Daylight Time) |

| Website | www |

History

editThe original inhabitants were Popoloca speakers, under the Aztec Triple Alliance.[8] Friar Juan de Rivas founded a small congregation in 1539 as part of the Spanish colonization and in 1750, construction began on Iglesia del Divino Salvador (Church of the Divine Savior).[8] In 1779 it became a town, and on 15 April 1930, it was declared a municipality under the governorship of Leonides Andrew Almazán.[8][9]

Geography

editThe total area of San Salvador Huixcolotla is 23.909 square kilometres (9.231 sq mi), of which 79% is devoted to agriculture and the remaining is 21% developed.[4][2]: 2 The four barrios are El Calvario, San Antonio, San Martín, and La Candelaria, and the three colonias are San Isidro, Dolores, and Benito Juárez.[4] It is surrounded to the north by the municipalities of Los Reyes de Juárez and Acatzingo; to the east by Acatzingo and Tecamachalco; to the south by Tecamachalco, Tochtepec, and Cuapiaxtla de Madero; and to the west by Cuapiaxtla de Madero and Los Reyes de Juárez.[2]

Climate

editThe typical range of temperatures is 12–18 °C (54–64 °F).[2]: 2 Typical annual rainfall is 1,100–1,300 millimetres (43–51 in).[2]: 2

Demographics

edit78.12% of the population lives in poverty.[4]: 15 As of 2015, electricity and sanitary systems are universal, but only 50.10% of households have piped water inside their homes.[4]: 17 90.25% of the population between age 6 and 14 can read and write.[4]: 18

Papel picado

editPapel Picado ("perforated paper," "pecked paper") is a decorative Mexican folk art made by cutting elaborate designs into sheets of tissue paper that were popularized in San Salvador Huixcolotla. It is thought to have originated from the pre-Hispanic practice of making religious offerings with amate bark paper.[10] Among the first makers were Juan Hernandez, Cristóbal Flores, Santiago Vivanco R., and Lauro Pérez Macías.[9] By the late 1920s, it had spread outside Puebla to Tlaxcala and is now used around the world in observations of Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead).[11][7] In addition to Día de Muertos, known locally as Todos Santos, papel picado is also commonly made to celebrate Semana Santa (the Holy Week of Easter), Mexican independence, and Christmas.[12][10]

In 1998 the governor of Puebla declared the town, in which 35% of the residents participate in this craft, a cultural heritage of the state.[10][13] Papel Picado from Huixcolotla is exported around the world via the Museo Nacional de Arte.[12]

Other culture

editAn annual fair celebrates the town's patron of San Salvador and runs from 6–14 August.[9] A typical dish is the eponymous mole poblana of the region.[9]

Further reading

edit- Manjarrez Rosas, Josefina (2013). Huixcolotla : el lugar de las espinas encorvadas : sus orígenes, tradiciones y costumbres ("Huixcolotla: the place of curved spines: its origins, traditions, and costumes") (1st ed.). Puebla, Pue, México: Benmérita Universidad de Puebla, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras. ISBN 9786074876604.

References

edit- ^ "Catálogo de Claves de Entidades Federativas y Municipios" (PDF). Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (Mexican Municipal Geographic Information Handbook), San Salvador Huixcolotla, Puebla (PDF) (in Spanish). 2009. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Instituto Electoral del Estado de Puebla (2018). "Planillas electas - Ayuntamientos". Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Plan de Desarrollo Municipal de San Salvador Huixcolotla (Municipal Development Plan of San Salvador Huixcolotla) 2019 - 2021" (PDF) (in Spanish). Municipality of San Salvador Xuixcolotla. 13 April 2019. p. 13. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2010). "Principales resultados por localidad 2010 (ITER)".

- ^ "Enciclopedia de los Municipios de México". Instituto Nacional para el Federalismo y el Desarrollo Municipal. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Papel Picado". Copal, Mexican Folk Art at its best Online. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Gobierno Municipal de San Salvador Huixcolotla". huixcolotla.gob.mx. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d "San Salvador Huixcolotla". Enciclopedia de los Municipios y Delegaciones de México (Mexican Encyclopedia of Municipalities and Delegations) (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b c Hernández, Maricarmen (31 October 2019). "Huixcolotla, cuna del papel picado ("Huixcolotla, cradle of papel picado")". El Sol de Puebla (in Spanish). Organización Editorial Mexicana. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ^ Álvarez Cordero, María del Carmen (2008). El arte de jugar y crear Tijereteando (PDF). LXIII Legislatura de la H. Cámara de Diputados. p. 82. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ a b Harvey, Marian (1987). "4". Mexican crafts and craftspeople: The papel picado of Huixcolotla. Philadelphia: Art Alliance Press. pp. 50–58. ISBN 9780879825126.

- ^ Palacios, Karina (25 October 2015). "Pueblo de papel picado". milenio.com (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved 31 May 2021.