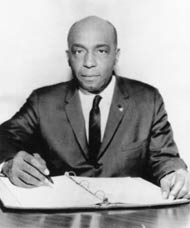

Samuel Wilbert Tucker (June 18, 1913 – October 19, 1990) was an American lawyer and a cooperating attorney with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).[1] His civil rights career began as he organized a 1939 sit-in at the then-segregated Alexandria, Virginia public library.[2][3] A partner in the Richmond, Virginia, firm of Hill, Tucker and Marsh (formerly Hill, Martin and Robinson), Tucker argued and won several civil rights cases before the Supreme Court of the United States, including Green v. County School Board of New Kent County which, according to The Encyclopedia of Civil Rights In America, "did more to advance school integration than any other Supreme Court decision since Brown."[4]

Samuel Wilbert Tucker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 18, 1913 Alexandria, Virginia, United States |

| Died | October 19, 1990 (aged 77) Richmond, Virginia, United States |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Howard University |

| Occupation | Civil rights attorney |

| Spouse | Julia E. Spaulding Tucker |

Early life and education

editTucker was born in Alexandria, Virginia, on June 18, 1913. His father, Samuel A. Tucker, a real estate agent and NAACP member, and teacher mother saw to his formal and informal education.[5] Tucker later said: "I got involved in the civil rights movement on June 18, 1913, in Alexandria. I was born black." Although Alexandria was less segregated than Richmond and Norfolk, it provided no high school for black children, so after graduating from 8th grade, he had to "bootleg" a high school education across the Potomac River in Washington, D.C., at Armstrong High School. Black Virginia children commuted by streetcar. In June 1927, when Tucker was 14, he, 2 brothers and a friend refused to leave their seats after a streetcar crossed the river into Alexandria, despite the request of a white woman who believed one of the seats was designated only for whites. She swore out a warrant charging them with disorderly conduct and abusive language, and the police levied no fine upon the 11 year old Otto Tucker, but fined Samuel Tucker $5 plus court costs and his older brother George $50 plus court costs, claiming that as eldest he should have known better. However, on appeal, an all-white jury found the young men not guilty.[6]

Tucker began drafting deeds to help his father at an early age, and also began reading the law books of Tom Watson, a lawyer who shared an office with the senior Tucker. Samuel attended Howard University whose chaplain Howard Thurman had become an outspoken proponent of Mahatma Gandhi's nonviolent resistance strategy and where Charles Houston established the nation's first program in civil rights law.[7] He earned his undergraduate degree in 1933. Tucker soon qualified for the Virginia bar exam based on his studies in Watson's law office, but had to wait until June 1934, when he reached age 21, to begin practicing law.[4] After two years with the Civilian Conservation Corps, Tucker and his friend George Wilson (a retired army sergeant) began in earnest dismantling segregation in Alexandria, first at the public library opened just 2 blocks from his home in August 1937, but which refused to issue cards to black residents.[7]

Legal career

editAt 14-years old, he had had a run-in with the law because a white woman accused him and his brothers of refusing to yield his seat in a "whites only" part of the trolley.[8] He was defended by a lawyer named Thomas Watson, who knew Tucker because he routinely ran errands for Watson and organized papers for him. [9] Tucker was admitted to the state bar in 1934, ironically in the same courtroom where a jury had acquitted him of the trolley car incident which occurred in 1927, and began practicing in Alexandria.[10]

Alexandria Library sit-in

editIn 1939, Tucker organized a sit-in at Alexandria Library, which refused to issue library cards to black residents. It had opened two years previously, replacing a previous whites-only subscription library that had been housed in a former home for Confederate veterans. Also, while the District of Columbia had built an integrated public library decades earlier with funds donated by Andrew Carnegie (and which Tucker had often visited, as he did a Black subscription library also in the District), the City of Alexandria had long ago refused similar funds, though Andrew Carnegie had lived and worked in Alexandria during the American Civil War, before making his fortune.[11] As a condition for their critical donation (which supplemented federal funds from the Public Works Administration and labor from the Works Progress Administration), the family of Kate Waller Barrett, insisted the City of Alexandria commit to funding the library's operating expenses. Thus monies from Black taxpayers were used to fund the library, although Tucker had previously shown that the library refused cards to Black prospective patrons.[12]

On August 21, 1939, five young black men whom Tucker had recruited and instructed – William Evans, Otto L. Tucker, Edward Gaddis, Morris Murray, and Clarence Strange – entered the library one by one, requested applications for library cards and, when refused, each one took a book off the shelf and sat down in the reading room until they were removed by the police. Tucker had instructed the men to dress well, speak politely and offer no resistance to the police so as to minimize the chance of the men being found guilty of disorderly conduct or resisting arrest. Tucker defended the men in the ensuing legal actions, which resulted in the disorderly conduct charges against the protestors being dropped by city attorney Armistead Boothe (who would later become a key figure in desegregating Virginia schools), and in a branch library being established for blacks.[2][13]

While the sit-in received a four-paragraph story in the local Alexandria Gazette newspaper and brief mention in the Washington Post, the Chicago Defender ran the story on its front page accompanied by a photograph of the arrest, noting that the protest was being viewed as a "test case" in Virginia.[14][15][16] Other African-American newspapers covered the legal action, reporting such developments as Tucker's cross-examination of the police, bringing forth an admission that had the men been white they would not have been arrested under similar circumstances.[2][17] While Tucker succeeded in defending the sit-in participants, he was not satisfied with the separate but equal resolution of creating a new branch library, the Robert H. Robinson Library, for blacks. In a 1940 letter to the librarian of the whites-only library, Tucker stated that he would refuse to accept a card to the new blacks-only branch library in lieu of a card to be used at the existing library.[18]

The photograph of the sit-in participants in jackets and ties calmly but resolutely being escorted from the library by uniformed police has itself become a learning aid in Alexandria. Periodically, the city has commemorated the sit-in and used it as a teaching opportunity about the Jim Crow segregation era, with students from Samuel W. Tucker Elementary donning similar attire, acting out the sit-in events and posing in recreations of the photograph.[14][19][20]

Wartime service, then move to Emporia

editWorld War II interrupted his fledgling legal practice. Tucker entered the army and served in the 366th Infantry, which saw combat in Italy. Tucker rose to the rank of major.

As World War II ended, the Virginia State Conference of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had W. Lester Banks[21] as executive secretary, Dr. Jesse M. Tinsley of Richmond and later E. B. Henderson of Falls Church as president, and Oliver W. Hill, Martin A. Martin and Spottswood Robinson as attorneys (the latter as liaison to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund). Tucker had returned to Alexandria but decided it had too many black lawyers, so he moved his law practice to Emporia, Virginia, in the heart of Southside Virginia.

There, Tucker was the only black lawyer. There were neither black judges nor black jurors. The white legal establishment in Greensville County often did not appreciate Tucker's criminal defense tactics, which attacked not only the evidence against his poor black clients, but racial imbalance in the system itself. For example, Tucker defended Jodie Bailey who, after drinking, stabbed the popular white proprietor of an automobile repair business during a charge dispute, and the man died. With NAACP help, Tucker established that in the previous three decades, no trial jury in Greensville County had included any black jurors. The Virginia Supreme Court overturned Bailey's conviction, but ordered a new trial, where he was convicted again.[22] Tucker also used a statistical argument in helping Martin A. Martin appeal the death sentences of the "Martinsville Seven". However, state and federal judges rejected the argument that since 1908 Virginia had executed 45 black men for raping white women, yet had executed no white man convicted of rape, so several clients were executed.[23]

Cooperating attorney for the NAACP under fire

editAs the Civil Rights Movement developed during the postwar era, Tucker came to have a central role in its legal battles in Virginia. He ultimately filed suits in nearly 50 counties, including Alexandria and neighboring Arlington and Fairfax.[4][24] By the time Brown v. Board of Education was decided in 1954 and 1955, the NAACP state legal staff had grown to a dozen cooperating attorneys (including Tucker), and had filed fifteen petitions requesting desegregation with local school boards by the spring of 1956.[25] However, U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd had vowed Massive Resistance to school desegregation, and that fall a special session of the Virginia General Assembly adopted (and Governor Thomas B. Stanley signed) a package of new laws to maintain segregation and close desegregating schools, which came to be known as the "Stanley Plan." That collection of bills also contained seven relating to NAACP activities, and expanded the definitions of the common law legal ethics offenses of barratry, champerty and maintenance.

Legislative committees led by James M. Thomson and John B. Boatwright attempted to use those new laws against the NAACP and cooperating attorneys. The Boatwright Committee subpoenaed NAACP membership lists, and issued reports in November 1957 and November 1958 accusing NAACP attorneys (including Tucker) of violating these laws and urging the Virginia State Bar to prosecute them. The Boatwright Committee specifically accused Tucker of soliciting "not less than 10 cases involving litigation" and claimed that some of his plaintiffs were signed up under false pretenses or had not realized they were becoming involved in litigation. Tucker became the only NAACP attorney that the Virginia State Bar attempted to prosecute and disbar for these expanded offenses. That prosecution began in February 1960, and the NAACP sent attorney Robert Ming from Chicago to defend Tucker before the state court in Emporia.[26] The case was repeatedly dismissed without prejudice (allowing prosecutors to re-file), particularly after Commonwealth's attorney Harold Townsend asserted that Tucker had no right to confront or even identify his accusers because this was a bar proceeding. The NAACP rallied to Tucker's defense in fighting what it viewed as an attempt to derail legal desegregation in Virginia.[27] It was transferred to Sussex County and finally dismissed in early 1962, although the judges orally reprimanded Tucker for his handling of an estate case.[28][29] In January 1963 in NAACP v. Button, the NAACP won other cases it had filed to stop enforcement of the last of the newly expanded laws. Furthermore, when in 1987, both Tucker and Oliver Hill received awards from Supreme Court Justice Lewis Powell on behalf of the Virginia Commission on Women and Minorities in the Legal System, Tucker alluded to that prosecution and noted that he was now being honored "for the very thing for which I'm being recognized today".[30]

In Richmond, Prince Edward and New Kent counties

editMeanwhile, in the early 1960s, Tucker formed the firm of Tucker and Marsh with Henry L. Marsh III in Richmond (which Hill would join in 1966). They and the NAACP participated in the long legal struggle to reopen the public schools in Prince Edward County, Virginia, which that county closed in 1959 to avoid desegregation, and which only reopened pursuant to court order in 1964.[31][32] Tucker also continued to fight against racial discrimination in jury selection.[33]

In 1966, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund named Tucker "lawyer of the year".[34] In 1967, for example, Tucker had about 150 civil rights cases before state and federal courts.[4]

Tucker's greatest legal achievement was probably Green v. County School Board of New Kent County, which challenged a freedom-of-choice plan the school board had enacted supposedly to desegregate the county schools on a voluntary basis, and which allowed white children to attend segregation academies at public expense. The case went to the Supreme Court of the United States, which heard statistical arguments from Tucker that the plan was no more than segregation by another name, 14 years after Brown. Then in May 1968, the Court ruled that the freedom-of-choice plan was an inadequate remedy and also decided that school boards had an "affirmative duty" to desegregate their schools, as the procedures improperly put a burden upon schoolchildren and their parents that Brown II had placed squarely on the School Board".[35] Patience for "mere deliberate speed" had run out. The next day, Tucker appeared before U.S. District Judge Robert Merhige Jr. in Richmond with 40 files of desegregation cases he wanted reopened. He also appeared a year later in Washington, D.C., before the Senate Judiciary Committee to oppose the nomination to the Supreme Court of Judge Clement Haynesworth, who had often upheld school segregation.[36]

In addition to bringing cases (and appearing before the Supreme Court four more times), Tucker was also active in the NAACP leadership, serving as chairman of the legal staff of the Virginia State Conference, as well as representing Virginia, Maryland and the District of Columbia on the national board of directors.[37]

Political activism and honors

editTucker twice ran for U.S. Congress in the 4th District (17 southern Virginia counties including Greensville) against segregationist Watkins Abbitt, one of U.S. Senator Harry F. Byrd's key allies—in 1964 as an Independent and in 1968 as a Republican. Though Tucker knew he would never win more than 30% of the vote against the powerful incumbent, he believed the battles important to register the protests as well as aspirations of black voters in the district.[38]

In 1976, the NAACP honored Tucker by awarding him the William Robert Ming Advocacy Award for the spirit of financial and personal sacrifice displayed in his legal work.[39]

Death and legacy

editTucker died on October 19, 1990, survived by his wife Julia. They had no children. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, sharing a tombstone with his elder brother George.[4] The Robert H. Robinson Library that opened in 1940 and closed in 1959 became home of the Alexandria Black History Museum.[40][41]

In 1998, Emporia, Virginia, dedicated a monument in Tucker's honor, with an inscription calling him "an effective, unrelenting advocate for freedom, equality and human dignity – principles he loved – things that matter."[4]

In 2000, Alexandria, Virginia dedicated a new school, Samuel W. Tucker Elementary School, to Tucker in honor of his life's work in the service of desegregation and education.[42] In 2014, the city's library began collecting donations for the Samuel W. Tucker Fund, to expand a collection relating to civil rights history.

Also in 2000, the Richmond City Council voted to rename a bridge formerly named after Confederate General J. E. B. Stuart after Tucker, despite controversy.[43]

In 2001, the Virginia State Bar's Young Lawyers Conference implemented the Oliver Hill/Samuel Tucker Institute, named for both Oliver Hill and Samuel Tucker. The institute seeks to reach future lawyers, in particular minority candidates, at an early age to provide them with exposure and opportunity to explore the legal profession they might not otherwise receive.[44]

Since 2001, the Oliver W. Hill & Samuel W. Tucker Scholarship Committee has presented scholarships to deserving first year law students at Virginia law schools and Howard University.[45]

References

edit- ^ S.J. Ackerman (June 11, 2000). "The Trials of S.W. Tucker". Washington Post. Retrieved August 16, 2016.[dead link] hence WASHPOST2000

- ^ a b c "America's First Sit-Down Strike: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In". City of Alexandria. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in". City of Alexandria. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Samuel Wilbert Tucker". Richmond Times. February 2000. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ J. Douglas Smith, Managing White Supremacy: Race, Politics and Citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia (University of North Carolina Press, 2002) p. 260

- ^ Smith at pp. 260-261

- ^ a b Smith at p. 261

- ^ Sullivan, WAPOST 2014, mid article

- ^ Perkins, ALEXTIMES 2014, under "overshadowed but not forgotten

- ^ Ackerman, WAPOST 2000, at p. 17

- ^ Mitchell-Powell, Brenda (2022). Public in name only : the 1939 Alexandria Library sit-in demonstration. Amherst. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-62534-657-5. OCLC 1285121224.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mitchell-Powell, pp. 95-97

- ^ "Remembering Injustices and Triumphs". Washington Post. January 30, 2009. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Pope, Michael (August 27, 2009). "Shhh! History Being Made: Remembering segregation and defiance on 70th anniversary of Alexandria's civil-rights protest at library". Alexandria Gazette Packet. Retrieved August 28, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Five Colored Youths Stage Alexandria Library 'Sit-Down': All to Face Court Today on Charge Of Disorderly Conduct for Efforts to Compel Extension of Book Privileges". Washington Post. August 22, 1939. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ Ackerman, WASHPOST@))! p. 17

- ^ "Va. Library War in Court Again". Baltimore Afro-American. September 2, 1939. p. 12. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ "Document of the Month: Letter from Samuel W. Tucker to Alexandria Library, February 13, 1940". City of Alexandria. February 2004. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "Alexandria Library Civil Rights Sit-In 70th Anniversary". City of Alexandria. Retrieved September 4, 2010.

- ^ "They led the way with 1939 Alexandria library protest: Re-enactment on 60th anniversary". Washington Times. August 22, 1999. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- ^ "Banks, W. Lester (1911–1986)". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Ackerman WASHPOST2000 at p. 18

- ^ Margaret Edds (2003). An expendable man: the near-execution of Earl Washington, Jr. NYU Press. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-0-8147-2222-0.

- ^ Ackerman, WASHPOST2000 at p. 24

- ^ Brian J. Daugherity, Keep on Keeping On (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2016) p. 46

- ^ Daugherity, at p. 90

- ^ "Case Dismissed". The Crisis. January 1961. Retrieved August 16, 2016.

- ^ "Va. Court Drops Charges Against NAACP Attorney". Baltimore Afro-American. February 3, 1962. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ Ackerman, WASHPOST2000 p.24

- ^ Ackerman WASHPOST 2000 at p. 25

- ^ "Virginia Must Reopen Schools Claims State's Supreme Court". The Sumter Daily Item (South Carolina). November 28, 1961. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ "Negro Attorney Hits Virginia School Plan". The Gadsen Times. Alabama. December 15, 1964. Retrieved July 10, 2010.

- ^ Tucker, S.W. (May 1966). "Racial Discrimination in Jury Selection in Virginia". Virginia Law Review. 52 (4): 736–750. doi:10.2307/1071544. JSTOR 1071544.

- ^ "LOCAL LAWYER, ADVOCATE OF CIVIL RIGHTS DIES AT 77". Richmond Times – Dispatch. October 19, 1990. Retrieved July 10, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ Brian J. Daugherity, Keep on Keeping On (University of Virginia Press 2016 at 124 et seq.

- ^ Ackerman, WASHPOST2000 at p. 28

- ^ "A Guide to the Samuel Wilbert Tucker Collection: Collection Number M56". Virginia Commonwealth University. 2001. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ Ackerman, WASHPOST2000, p. 29

- ^ "NAACP Legal Department Awards". NAACP. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ Nancy Noyes Silcox, Samuel Wilbert Tucker: The story of a Civil Rights Trailblazer and the 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in (Fairfax: History4all, 2014) pp 75-77

- ^ Char McCargo Bah, Christa Watters, Audrey P. Davis, Gwendolyn Brown-Henderson and James E. Henson Sr., African-Americans of Alexandria, Virginia (Charleston, The History Press, 2013), p. 84

- ^ "ACPS | About Mr. Tucker". March 4, 2016. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ Carrie Johnson (February 15, 2000). "TWO BRIDGES TO GET NEW NAMES GENERALS ARE OUT; RIGHTS ACTIVISTS ARE IN". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved July 3, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "Oliver Hill/Samuel Tucker Prelaw Institute". Virginia State Bar. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ "Scholarship History" (PDF). Greater Richmond Bar Foundation. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

Further reading

edit- Ackerman, S.J. (Summer 2000). "Samuel Wilbert Tucker: The Unsung Hero of the School Desegregation Movement". Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 28 (28): 98–103. doi:10.2307/2678720. JSTOR 2678720.

- Brenda Mitchell-Powell (2022). Public in Name Only: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in Demonstration; Studies in print culture and the history of the book. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 248ff. ISBN 978-1-6137-6935-5.

- Nancy Noyes Silcox (2014). Samuel Wilbert Tucker: The Story of a Civil Rights Trailblazer and the 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In. History4All, Incorporated. p. 111ff. ISBN 978-1-9342-8523-7.

- Jill Ogline Titus (2011). Brown's Battleground: Students, Segregationists, and the Struggle for Justice in Prince Edward County, Virginia. University of North Carolina Press. p. 126ff. ISBN 978-0-8078-3507-4.

- Smith, J. Douglas (2002). Managing white supremacy: race, politics, and citizenship in Jim Crow Virginia. University of North Carolina Press. p. 259ff. ISBN 978-0-8078-2756-7.

- Wallenstein, Peter (2004). Blue Laws and Black Codes: Conflict, Courts, and Change in Twentieth-Century Virginia. University of Virginia Press. p. 83ff. ISBN 978-0-8139-2261-4.

External links

edit- America's First Sit-Down Strike: The 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-In – Alexandria Black History Museum lesson plan

- 1956 Television Interview of Samuel Tucker – Archived by University of Virginia

- The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia: The Closing of Prince Edward County's Schools Archived December 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine – Virginia Historical Society

- 70th Anniversary of Alexandria Library’s Historic Sit-in – City of Alexandria podcast

- 1939 Alexandria Library Sit-in Video – C-SPAN