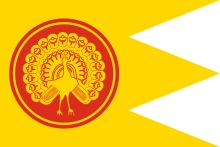

The Royal Armed Forces (Burmese: တပ်မတော်,[note 1] [taʔmədɔ̀]) were the armed forces of the Burmese monarchy from the 9th to 19th centuries. It refers to the military forces of the Pagan Kingdom, the Kingdom of Ava, the Hanthawaddy Kingdom, the Toungoo dynasty and the Konbaung dynasty in chronological order. The army was one of the major armed forces of Southeast Asia until it was defeated by the British over a six-decade span in the 19th century.

| Royal Armed Forces | |

|---|---|

| ‹See Tfd›တပ်မတော် Tatmadaw | |

| |

| Active | 849–1885 |

| Country | |

| Branch | Royal Bloodsworn Guard Guards Brigade Ahmudan Regiments Artillery Corps Elephantry Corps Cavalry Regiments Infantry Regiments Navy |

| Type | Army, Navy |

| Role | Military force |

| Size | 70,000 men at its height |

| Engagements | Mongol invasions Forty Years' War Toungoo–Hanthawaddy War Burmese–Siamese wars Konbaung–Hanthawaddy War Sino-Burmese War Anglo-Burmese Wars |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Kyansittha, Minye Kyawswa, Bayinnaung, Binnya Dala, Smim Payu, Saw Lagun Ein, Alaungpaya, Maha Nawrahta, Pierre de Milard, Maha Thiha Thura, Maha Bandula, Myawaddy Mingyi U Sa |

The army was organised into a small standing army of a few thousand, which defended the capital and the palace, and a much larger conscript-based wartime army. Conscription was based on the ahmudan system, which required local chiefs to supply their predetermined quota of men from their jurisdiction on the basis of population in times of war.[1] The wartime army also consisted of elephantry, cavalry, artillery and naval units.

Firearms, first introduced from China in the late 14th century, became integrated into strategy only gradually over many centuries. The first special musket and artillery units, equipped with Portuguese matchlocks and cannons, were formed in the 16th century. Outside the special firearm units, there was no formal training program for the regular conscripts, who were expected to have a basic knowledge of self-defense, and how to operate the musket on their own. As the technological gap between European powers widened in the 18th century, the army was dependent on Europeans' willingness to sell more sophisticated weaponry.[2]

While the army held more than its own against the armies of the kingdom's neighbors, its performance against more technologically advanced European armies deteriorated over time. It defeated the Portuguese and French intrusions in the 17th and 18th centuries respectively but the army could not stop the advance of the British in the 19th century, losing all three Anglo-Burmese Wars. On 1 January 1886, the millennium-old Burmese monarchy and its military arm, the Royal Burmese Armed Forces, were formally abolished by the British.

The Burmese name Tatmadaw is still the official name for today's armed forces as well in the Burmese names of their opponents such as the People's Defence Force which name is pronounced Pyithu Karkweyay Tatmadaw (ပြည်သူ့ကာကွယ်ရေးတပ်မတော်).

Origins

editThe Royal Burmese Army had its origins in the military of the early Pagan Kingdom circa mid-9th century. The earliest recorded history was the foundation of the fortified city of Pagan (Bagan) in 849 by the Mranma, who had entered the Upper Irrawaddy valley along with the Nanzhao raids of the 830s that destroyed the Pyu city states. The early Pagan army consisted mainly of conscripts raised just prior to or during the times of war. Although historians believe that earlier kings like Anawrahta, who founded the Pagan Empire, must have had permanent troops on duty in the palace, the first specific mention of a standing military structure in the Burmese chronicles is 1174 when King Narapatisithu founded the Palace Guards—"two companies inner and outer, and they kept watch in ranks one behind the other". The Palace Guards became the nucleus round which the mass levy assembled in war time.[3]

Organisation

editThe Royal Burmese Army was organized into three general tiers: the Palace Guards, the Ahmudan Regiments, and the field levies. Only the first two were the standing military. They protected the sovereign and the capital region, and formed the nucleus of the armed forces in wartime. The third, the field levies or conscripts, were usually raised just prior to or during wartime, and provided manpower to resist attacks and project power beyond the boundaries of the empire.[4] Most of the field levy served in the infantry but the men for the elephantry, cavalry, artillery and naval corps were drawn from specific hereditary villages that specialized in respective military skills.

Royal Household Guards

editRoyal Bloodsworn Bodyguard

The King and the royal family's personal protection are under the Royal Thwei-thauks (သွေးသောက်) or Bloodsworn Guards, who were sworn under a blood oath, hence their name. They are generally made up of royal relatives and the most trusted courtiers. The term sometimes refer to the close companions of the King. The most famous example is the ethnic Mon General Binnya Dala, who was a thwei-thauk of Bayinnaung. Dala describes the men, who had sworn the blood oath as "All [of us], his chosen men, in fact, whether Shans, Mons or Burmans... declared ourselves willing to lay down our lives [for him]."[1]

The Bloodsworns were never a permanent military body and their loyalty was personal to the individual king. Whenever a new king reigns, he would form his own bodyguard of Bloodsworn men, usually from his own retainers or relatives.[5]

Palace Guard Regiments

The Guards Division consisted of four brigades, each of which resided in barracks outside the palace, and designated by the location in relation to the place: Front, Rear, Left and Right. The captain of each brigade was called winhmu (‹See Tfd›ဝင်းမှူး [wɪ́ɴ m̥ú]). The men generally were gentry, and selected for their trustworthiness.[3] Servicemen in the Capital Regiments and the Royal Palace Guards were selected from trusted hereditary ahmudan village located near the capital or the king's ancestral/appanage region. Prior to the early 17th century, each viceroy also maintained his own smaller version of household guards and ahmudan regiments especially at the border regions—essentially a garrison. The existence of competing armies was a constant source of political instability especially during the 14th to 16th centuries when high kings regularly faced rebellions by their own kinsman viceroys who also wanted to be king. It changed in 1635 when all appanage-holders (viceroys, governors and sawbwas) along with their retainers were required to abolish their local forces and instead reside at the capital for long periods. Gentry youths in Upper Burma were required to serve in the military or non-military service of the king either in the corps of royal pages or in the capital defence regiments. At a lower social level, tens of thousands of military and non-military were required to serve capital service rotas lasting from several months to three years.[6]

The Guard Regiments were notably for including a large number of non-Burmese in their ranks. In the Konbaung era, the interior Palace was guarded by companies of Laotian, Shan and Northern Thai soldiers. They served in a similar function to the Swiss Guards of European monarchs in the 17th and 18th century.[5] Burmese of European descendants known as the Bayingyi are noted to serve in these regiments as well.

Ahmudan service system

editService to the army was organized according to the ahmudan (‹See Tfd›အမှုထမ်း [ʔə m̥ṵ dáɴ]) system, which had been in place since the Pagan era. Ahmudan literally means civil service. This required local chiefs to supply their predetermined quota of men from their jurisdiction on the basis of population in times of war. The village chiefs responded to requests from their respective mayors who in turn responded to those of governors and viceroys/sawbwas, who in turn responded to the high king.[1] The quotas were fixed until the 17th century when restored Toungoo kings instituted variable quotas to take advantage of demographic fluctuations.[7] Some hereditary ahmudan villages, particularly those that had descended from European and Muslim corps, specialized in providing more skilled servicemen such as gunners and cannoneers. The selection of conscripts was left to the local headmen. Conscripts could provide a substitute or pay a fee in lieu of service. Conscripts often had to be driven into battle, and the rate of desertion was always high.[4]

Command

editThe command structure followed the three-tier organizational structure. The king was the commander-in-chief although in practice most kings appointed a commander-in-chief, usually from the ranks of the royal house or from the top command of the Palace Guards, to lead the campaigns. The winhmus formed the core command of most military operations although more prominent military campaigns would ostensibly be led by a close member of the royalty—at times, the king himself or the king's brother or son, or other times a senior minister of the court. (Although Burmese history is often dominated by the portrayals of warrior kings' battlefield exploits, the high royalty's leadership on the battlefield was largely symbolic in most cases.)

Directly below the generals were the local chiefs and their deputies who commanded the regiment commanders. The use of local chiefs was a necessary element of the army's organizational structure especially in Toungoo and Konbaung eras because the army was made up of levies from all parts of the empire. Shan sawbwas (chiefs) and Mon commanders routinely led their own regiments throughout the imperial era. Outstanding ethnic commanders also led larger operations and even entire campaigns, especially in Ava and Toungoo periods (14th to 18th centuries). (King Bayinnaung's best and most relied upon general Binnya Dala was an ethnic Mon while many Shan sawbwas led multi-regiment armies throughout Toungoo and Konbaung eras.)

The main field military unit of the army was the regiment. A 1605 royal order decreed that the fighting forces should be organised as follows: each regiment shall consist of 1000 foot soldiers under 100 company leaders called akyat (‹See Tfd›အကြပ် [ʔə tɕaʔ]), 10 battalion commanders called ahsaw (‹See Tfd›အဆော် [ʔə sʰɔ̀]) and 1 commander called ake (‹See Tfd›အကဲ [ʔə kɛ́]), and all must be equipped with weapons including guns and cannon. In the early 17th century, a typical regiment consisting of 1000 men was armed with 10 cannon, 100 guns and 300 bows. Moreover, the camp followers should include expert catchers of wild elephants as well as musicians and astrologers.[8] An infantry unit was generally divided between daing or shields, musketeers and spearmen.[5]

Special branches

editThe infantry was the backbone of the wartime Burmese army, and was supported by special branches—the elephantry, cavalry, artillery, and naval corps. These special branches were formed by the men from certain hereditary villages that provided the men with specialized skills. In a typical Toungoo or Konbaung formation, a 1000-strong infantry regiment was supported by 100 horses and 10 war elephants.[9]

Elephantry

editThe main use of war elephants was to charge the enemy, trampling them and breaking their ranks. Although the elephantry units made up only about one percent of the overall strength, they were a major component of Burmese war strategy throughout the imperial era. The army on the march would bring expert catchers of wild elephants.

During the 19th century elephants were still used to carry armed men and artillery; one elephant could carry a battery of eight pieces[10]

In this period elephants were fitted Howdahs and covered in armor; both made of an iron frame covered with two layers of buffalo hide. Each Howdah carried four gunmen; the gunmen climbed through a rope ladder which was hung on a hook afterwards. Two long spears were hung on the side of the Howdah to be used in melee [10]

Cavalry

editWhile not as pronounced as in Europe and other similar cultures, mounted warriors hold an elite position in Burmese society, "because horses and elephants are worthy of kings; they are excellent things, of power."[5]

The Myinsi (မြင်းစီး lit. Horse rider or Cavalier) served as a knightly class of sorts being the only class of people allowed mobility throughout the kingdom without permission and ranking only below the noble-ministers. The one of the highest military rank is termed myinhmu mintha (literally cavalry prince) or perhaps better translates as knight commander in English.[5]

From the 17th century onward, cavalry troops made up about 10% of a typical regiment. The men of the cavalry were drawn mainly from hereditary villages in Upper Burma. One of the core areas that provided expert horsemen since the early 14th century was Sagaing. The Sagaing Htaungthin (‹See Tfd›စစ်ကိုင်း ထောင်သင်း [zəɡáɪɴ tʰàʊɴ ɵɪ́ɴ]; lit. "Thousand-strong Regiment of Sagaing") cavalry regiment, founded in 1318 by King Saw Yun of Sagaing, was maintained up till the fall of Burmese monarchy. The formation of the regiment consisted of nine squadrons, from each named after the hereditary village.[11]

| Cavalry name | Strength |

|---|---|

| Tamakha Myin ‹See Tfd›တမာခါး မြင်း |

150 |

| Pyinsi Myin ‹See Tfd›ပြင်စည် မြင်း |

150 |

| Yudawmu Myin ‹See Tfd›ယူတော်မူ မြင်း |

150 |

| Letywaygyi Myin ‹See Tfd›လက်ရွေးကြီး မြင်း |

150 |

| Letywaynge Myin ‹See Tfd›လက်ရွေးငယ် မြင်း |

70 |

| Kyaungthin Myin ‹See Tfd›ကြောင်သင်း မြင်း |

50 |

| Myinthegyi Myin ‹See Tfd›မြင်းသည်ကြီး မြင်း |

50 |

| Hketlon Myin ‹See Tfd›ခက်လုံး မြင်း |

30 |

| Sawputoh Myin ‹See Tfd›စောပွတ်အိုး မြင်း |

30 |

Bayinnaung often used massed cavalry extensively in both field and siege actions. In a battle against the Siamese under Phraya Chakri, Bayinnaung used a small force of Burmese cavalry to force the Siamese garrisons to sally from their stockade allowing the hidden Burmese infantry to cut them off from the stockades. The cavalry unit returned to the battle with the rest of its unit then charged the Siamese routing them towards Ayutthaya.[12]

Later in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Burmese cavalry was divided into the Bama, Shan and Meitei cavalry. The Meitei Cassay Horse (‹See Tfd›ကသည်း မြင်း), was the elite light cavalry unit in the Burmese cavalry corps. The Cassay Horse along with other Burmese cavalry units were reported to play important roles during the First Anglo-Burmese War engaging the British cavalry in various skirmishes.[13] At the Battle of Ramu, the Burmese cavalry dealt the final blow to the British force in the ending stages of the battle when they charged the faltering British Indian regulars.[14] Although they proved themselves well in skirmishes, both the Cassay Horse and other Burmese cavalry units were unable to defeat the heavier British and Indian cavalry in the open field in all the Anglo-Burmese wars.

The royal court continued to retain a significant cavalry force into the 1870s.

Artillery

editDuring the 16th century, the Burmese artillery and musketeer corps were originally made up exclusively of foreign (Portuguese and Muslim) mercenaries. But by the mid-17th century, mercenaries, who had proven politically dangerous as well as expensive, virtually had disappeared in favour of cannoneers and matchlockmen in the Burmese military ahmudan system. However, the men who replaced the mercenaries were themselves descendants of the mercenaries who had settled in their own hereditary villages in Upper Burma where they practiced their own religion and followed their own customs.[15]

During the 19th century the artillery corps (Mingy Amyauk) had a permanent strength between 500 and 800 men. Including an elephant battery, buffalo batteries, and lighter guns carried by men. These were under command of the Amyauk Wun a senior palace official.[16]

Batteries usually had ten guns each and were commanded by a Amyauk Bo assisted by an assistant called the Amyauk Saye. Battery subdivisions were commanded by Thwethaukgyis[16]

Regular artillerymen seem to have mostly accompanied standing armies; it is likely most men manning defensive positions were recruited locally. At Rangoon in 1856 prisoners were released to man the guns; which they were chained to.[16]

Navy

editThe naval arm of the army consisted mainly of river-faring war boats. Its primary missions were to control the Irrawaddy, and to protect the ships carrying the army to the front. The major war boats carried up to 30 musketeers and were armed with 6- or 12-pounder cannon.[15] By the mid-18th century, the navy had acquired a few seafaring ships, manned by European and foreign sailors, that were used to transport the troops in Siamese and Arakanese campaigns.

Note that the Arakanese and the Mon, from the maritime regions, maintained more seaworthy flotillas than inland riverborne "navy" of the Royal Burmese Army. The Arakanese in particular fielded a formidable seagoing navy that terrorised the coasts of Bay of Bengal during the 15th and 17th centuries.

Communities on the Irrawady were obliged to provide war boats (Tait He); a substantial number of war boats was also maintained at the capital. Most vessels were crewed by local levies but a small number of crewmen was recruited from the standing army's ''Marine Regiment''. This unit had a thousand men and was commanded by the Hpaungwun whose his second commando was the Hlethin Bo[17]

Fireships were used against the British between 1824 and 1825; those were bamboo rafts carrying clay jars filled with cotton and petroleum. Some Fireships were longer than a hundred feet; and divided into many pieces, connected by hinges; when caught on the bow of another ship the current would wrap the raft around it.[17]

Attire

editThe most iconic image of the Burmese royal army is the layered wavy collars that extend to the shoulders worn by officers and officials. The formal attire of the field infantry was minimalist. Ordinary foot soldiers were typically dressed only in thick quilted cotton jackets called taikpon (‹See Tfd›တိုက်ပုံ), even in the campaigns that required them to cross thick jungles and high mountains. Their dresses were hardly enough to keep the conscripts warm during the army's punishing, many-week-long marches. The palace guards wore more ostentatious uniforms—Bayinnaung's palace guards wore "golden helmets and splendid dresses"—and rode horses and elephants. Tabinshwehti's cavalry were described to be wearing "curiasses, breastplates, and skirts of mail, as well as lances, swords and gilded shields." Their mounts were "richly caparisoned horses".[18]

In 1800, Symes noted that Burmese troops wore loose scarlet frocks with conical caps with a plume and drawers reaching below the knees. In the First Anglo-Burmese War, a Western observer at the Burmese capital noted of the army leaving for the front: "each man was attired in a comfortable campaign jacket of black cloth, thickly wadded and quilted with cotton".[3][19]

Western-influenced uniforms became common after the Second Anglo-Burmese War during the reign of King Mindon. Burmese uniforms in the 1860s consisted of green jackets, red striped pasos and red helmets though regular infantry wore civilian white jackets.[20] A European observer described the Burmese cavalry dressed in "red jackets and trousers, a few wearing a red jerkin over these, and still fewer dressed in the full uniform of the cavalry, shoulder-pieces, gilt helmet, with ear-pieces and embroidered jerkin; all had the white saddle-flap and high-peaked pommel and cantle. The men were armed with a spear and a sword each, with the latter being, as a rule, a Burmese dha (sword), but a few had the sword of a European shape with a scabbard of brass or steel."[20] Charney suggests that uniforms were worn only on special occasions as they were provided by the court with a new one being supplied each year.[13] Instead, the soldiers were identified by tattoo marks on the backs of their neck.

Strength

editStanding army

editThe size of the regular standing army, the Palace Guards and the Capital Defense Corps, was in low thousands only, even in wartime. Even under Bayinnaung, the much celebrated soldier king whose reign was marked by a series of constant military campaigns, the Capital Defense Corps was only about 4000 strong. In 1826, right after the First Anglo-Burmese War, a British envoy reported a capital garrison of 4000 to 5000. In peacetime, the size was even smaller. In 1795, another British envoy found 2000 troops, including about 700 palace guards, at the capital Amarapura.[3]

Wartime army

editThe general strength of the wartime army varied greatly depending on a number of factors: the authority of the king, the population of the territories he controlled, and the season of year. Because most of the conscripts were farmers, most wars were fought during the dry season. The famous Forty Years' War was largely fought during the dry season, and armies went back to till the land during the rainy season. Only a few times in the imperial era was the decision to extend the campaign to the rainy season made, most notables being the First Anglo-Burmese War and the Burmese–Siamese War (1765–1767).

The maximum size of the army ultimately depended on that of the overall population from which to draw levies. During the Ava period (1364–1555), when the country was divided into several small fiefdoms, each petty state could probably have mobilized 10,000 men at most. (The Burmese chronicles routinely report numbers at least an order of magnitude higher but these numbers have been dismissed by historians.) The latter kingdoms (Toungoo and Konbaung dynasties) with larger populations certainly fielded larger armies. The crown practiced the policy of having conquered lands provide levies to his next war effort. Historian GE Harvey estimates that Bayinnaung likely raised about 70,000 men for his 1568–1569 invasion of Siam while early Konbaung kings likely raised armies of 40,000 to 60,000.[21]

Military technology

editThe main weaponry of the infantry largely consisted of swords, spears and bow and arrows down to the late 19th century although the use of firearms steadily increased starting from the late 14th century. The infantry units were supported by cavalry and elephantry corps. War elephants in particular were the heavily sought after as they were used to charge the enemy, trampling them and breaking their ranks. Elephantry and cavalry units were used in warfare down to the 19th century. Encounters with Burmese war elephants were recorded by the Mongols in their late 13th century invasions of Burma.

Introduction of firearms

editThe introduction of firearms first came to Burma from Ming China in the late 14th century. State-of-the-art Chinese military technology reached northern mainland Southeast Asia by way of Chinese traders and renegade soldiers, who despite the Ming government's prohibition, actively smuggled primitive handguns, gunpowder, cannon and rockets. True metal barreled handguns, first developed in 1288, and metal barreled artillery from the first half of 14th century had also spread.[22][23] During the same period, Chinese and Arab-style firearms were also in use at the coast.[24]

The lack of firearms was a major factor in the army's lackluster performance against the smaller Shan states in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. The Shans had soon learned to replicate Chinese arms and military techniques, and were able to strengthen their position not only against Ava but also against Ming China itself. Shan states at the Yunnan border (in particular, Mohnyin and Mogaung) were the first soon put this military technology to use. Despite their relatively small size, Mogaung in the 14th century and Mohnyin in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, raided much larger Upper Burma for decades.

However, this early technological advantage of the Shan states vis-a-vis Ava was gradually neutralized by the continued spread of the firearms. By the mid-16th century, the introduction of better firearms from Europe had reversed the positions, and helped the Toungoo dynasty annex all of the Shan states for the first time.[25]

Arrival of European firearms

editWestern firearms and early modern warfare first arrived at the shores of Burma in the early 16th century by way of Portuguese mercenaries. The matchlock musket, first invented in Germany in the mid-15th century, arrived to Burma in large quantities starting in the 1530s. Cannon and matchlocks supplied by Portuguese mercenaries proved superior in accuracy, safety, ballistic weight and rapidity of fire.[25][26]

Firearms became a pillar of the new imperial order. Starting with the Hanthawaddy Kingdom, foreign gun makers were encouraged to establish foundries, which were even able to export to neighbouring countries. For example, some of the firearms found in Malacca when the Portuguese took it in 1511 came from gun foundries in Lower Burma.[26][27] Royal artisans produced gunpowder and matchlocks throughout the Toungoo period. Guns were also secured from China and various Tai-Shan realms. By the 17th century, mainland Southeast Asia was "fairly awash with guns of every kind".[23] In some late 16th century campaigns, as high as 20–33 percent of the troops were equipped with muskets. In 1635, 14 to 18 percent of Burma's royal troops used firearms.[8] Expanding maritime trade after mid-18th century, a coincident increase in the quality of European handguns, and the frequency of warfare all contributed to increased integration of firearms. By 1824, on the eve of First Anglo-Burmese War, anywhere from 29 to 89 percent of Konbaung field armies were equipped with guns, with 60 percent a reasonable average.[15]

The cannon were also integrated to siege warfare although the Burmese like many other Southeast Asians valued the cannon more for their imposing appearance and sound than actual usefulness. By the mid-18th century, small 3-inch calibre cannon were widely used in the sieges Pegu and Ayutthaya.[28][29]

However, the quality of domestically produced and Chinese firearms perpetually remained inferior to European ones. The court concentrated on procuring coastal imports, which—given the demands of campaigning and the guns' rapid deterioration in tropical conditions—became an endless task. Thus a principal responsibility of coastal governors was to procure firearms through purchases and levies on incoming ships. Royal agents also purchased guns as far afield as India and Aceh; while diplomatic approaches to Europeans typically focused on this issue. King Bodawpaya (r. 1782–1819) obliged Burmese merchants plying the Irrawaddy to supply specified quantities of foreign guns and powder in lieu of cash taxes.[15]

Widening technology gap with European powers

editThe quality gap between locally manufactured guns and European arms continued to widen as new rapid advances in technology and mass production in Europe quickly outstripped the pace of developments in Asia. Important developments were the invention of the flintlock musket and mass production of cast-iron cannon in Europe. The flintlock was much faster, more reliable and more user-friendly than the unwieldy matchlock, which required one hand to hold the barrel, and another to adjust the match and pull the trigger.[30]

By the late 17th century, gunmaking was no longer a relatively simple affair as had been the case with the matchlock but had become an increasingly sophisticated process that required highly skilled individuals and complex machinery. Southeast Asian rulers could no longer depend on Europeans or foreign Asians to produce guns locally that were on par with those manufactured in Europe or European foundries in Asia. The Burmese like other Southeast Asians were dependent on the goodwill of the Europeans for the supply of their guns. The Europeans for their part were loath to provide the Southeast Asians with the means to challenge them. As a result, early Konbaung kings continually sought reliable European arms but rarely received them in quantity they wanted. Or sometimes, they could not pay for them. In the 1780s, the Chinese trade embargo of Burmese cotton greatly limited the crown's ability to pay for more advanced foreign firearms. Bodawpaya had to rely on domestic musket production, which could produce only low-tech matchlocks while the rival Siamese were transitioning to more advanced European and American supplied flintlocks.[31] Still, the flintlock slowly began to replace the less efficient and less powerful matchlock in Burma. The army also began to obtain cast-iron cannon.[26][27]

By the early 19th century, the Europeans had gained a considerable superiority in arms production and supply in Southeast Asia. The growing gap was highlighted in the progressively worse performance of the army in the three Anglo-Burmese Wars (1824–1885). The gap was already considerable even on the eve of the first war, in which Burmese defences fared best. The palace arsenal had about 35,000 muskets but they were mostly rejects from French and English arsenals. The gunpowder was of such poor quality that British observers of the era claimed that it would not have been passed in the armies of Indian princes. The British also considered Burmese artillery "a joke".[32] Not only did the skills of Burmese artillery men compare badly to those of the British ones, Burmese cannon technology was several generations behind. In the First Anglo-Burmese War, the Burmese cannon were mostly old ship guns of diverse calibre, and some of them 200 years old. Some of them were so old that they could be fired no often than once in 20 minutes.[33] When they did, they still fired only non-exploding balls whereas the British troops employed exploding Congreve rockets.[34][35] The gap only widened even further after the Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852–1853), after which the British had annexed Lower Burma, and held a stranglehold on arm supplies to a landlocked Upper Burma. In response, the Burmese, led by Crown Prince Kanaung instituted a modernisation drive that saw the foundation of a gun and munitions foundry and a small artillery factory. But the drive sputtered after the prince's assassination in 1866. An 1867 trade agreement with the British government permitted the Burmese to import arms, but Britain rebuffed a Burmese request to import rifles from them.[36]

In the 1840s the Burmese began to construct larger European style ships. In 1858 Mindon Min purchased a small two funneled side wheel steamer at Calcutta; this was the first of several British made vessels. By 1866 Mindon Min had a second steamer; both were used to crush a rebellion. By 1875 there were three such ''king's ships''. These boats were crewed by men from the marine regiment and used as merchant vessels in peace time.[17]

By 1885 there were 11 such ships; including an ocean steamer; 2 gunboats with 8 guns each and 8 smaller steamers.[17]

By 1885 Thibaw had acquired a ''Mitraileuse'' of unknown type, with a limited amount of ammunition.[16]

Training

editThe army maintained a limited regular training regiment for its Palace Guards and Capital Defense Corps but no formal training program for its conscripts.

Pwe-kyaung system

editTo train the conscripts, the army relied on the non-state funded pwe-kyaung (‹See Tfd›ပွဲကျောင်း [pwɛ́ dʑáʊɴ]) monastic school system at the local level for the conscripts' basic martial know-how. The pwe-kyaungs which, in addition to a religious curriculum, taught secular subjects such as astrology, divination, medicine (including surgery and massage), horse and elephant riding, boxing (lethwei) and self defence (thaing). This system had been in place since Pagan times.[37][38] In the lowland Irrawaddy valley but also to a lesser extent in the hill regions, all young men were expected to have received a basic level of (religious) education, and secular education (including martial arts) from their local Buddhist monastery.

Special units

editNevertheless, the pwe kyaung system was not sufficient to keep up with advances in military technology. In the 17th century, the army provided training in the use of firearms only to professional gun units. The average soldier was expected to fend for himself. Dutch sources record that when Burmese levies were mobilised in times of war, they were required to bring their own gunpowder, flints and provisions. It follows that when these recruits marched off to war with their own gunpowder and flints, they were clearly expected to use the guns that were normally kept under strict guard in a centralized magazine, and released to soldiers only during training or in times of war.[4] Despite the majority of the conscripts not having received any formal training, the British commanders in the First Anglo-Burmese War observed that the musketry of the Burmese infantrymen under good commanders "was of formidable description".[32]

The Palace Guards and the Capital Defense Corps received minimal formal military training. Western observers noted that even the elite Capital Defense Corps in the 19th century were not strong at drill.[3] Special branches such as gun and cannon units also received some training. In the 1630s, foreign and indigenous gun regiments not only inhabited the land they had been granted, but that in the outfitting of a unit of 100 gunners, each man was issued a gun and all necessary supplies.[4] Nonetheless, the skills of Burmese artillery men remained poor. In 1661, Dutch observers at the Burmese capital noted that Burma was more in need of expert cannoneers than cannon. They noted that most of King Pye's arsenal of cannon remained unused because he lacked skilled cannoneers.[8] Such was the lack of skilled artillery men that the French cannoneers captured by Alaungpaya quickly became the leaders of the Burmese artillery corps in the second half of the 18th century.

Artillery

editThe Burmese artillery usually did not practice regularly; although Maha Bandula attempted to encourage it in 1824. Other attempts were made in the 1830s under kings Bagyidaw and Tharrawady. In the 1850s Crown Prince Kanaung was able to enforce regular practice at the central artillery corps in Amapura for 18 months with help from foreign instructors; this regime was discontinued in late 1855 [16]

A French advisor later attempt to reintroduce artillery practice; but this was forbidden by king Mindon Min who was disturbed by the noise.[16]

Strategy

editThe army's war strategy and fighting tactics generally remained fairly constant throughout the imperial era. The infantry battalions, supported by the cavalry and elephantry, engaged the enemy in the open battlefield. The arrival of European firearms did not lead to any major changes in battle techniques or transform traditional ideas of combat. Rather, the new weapons were used to reinforce traditional ways of fighting with the dominant weaponry still the war elephants, pikes, swords and spears. In contrast to European-style drill and tactical co-ordination, Burmese field forces generally fought in small groups under individual leaders.[2]

Siege warfare and fortified defences

editThe siege warfare was a frequent feature during the small kingdoms period (14th to 16th centuries) when the small kingdoms or even vassal states maintained fortified defenses. By the 1550s, the Portuguese cannon had forced a shift from wood to brick and stone fortifications. Moreover, the Portuguese guns may have encouraged a new emphasis on inflicting casualties, rather than or in addition to taking prisoners.

In the early 17th century, the Restored Toungoo kings required the vassal kings to reside at the capital for long periods, and abolished their militias and their fortified defences. When the Dutch merchants visited Burma in the mid-17th century right after the change was instituted, they were amazed that even the major towns except the capital did not have any fortified defences. They found that the Burmese kings distrusted the vassal states, and instead preferred to rely on the country's numerous toll stations and watchtowers from where messengers could be rushed to the capital.[4]

Despite the royal prohibition, the fortifications returned to the scene during the Burmese civil war of the 1750s, which featured a series of sieges by both sides. In the 19th century, forts along the Irrawaddy was a major part of Burmese strategy to defend against a potential British invasion. In practice, however, they did little to withstand British firepower.

Scorched earth tactics

editA major strategy of the army was the use of scorched earth tactics, mainly in times of retreat but also in times of advance. They would burn and destroy everything in sight that could be of use to the enemy, crops and infrastructure (wells, bridges, etc.). At times, the entire region at the border was destroyed and depopulated to create a buffer zone. For example, in 1527, King Mingyi Nyo depopulated and destroyed the infrastructure of the entire Kyaukse–Taungdwingyi corridor between Ava (Inwa) and his capital Toungoo (Taungoo).[39] Likewise, the Burmese had left the entire Chiang Mai region depopulated and its infrastructure destroyed in the wake of their 1775–1776 war with Siam.

The army also used scorched earth tactics as a means to intimidate the enemy and to secure easier future victories. The ruthless sacks of Martaban in 1541 and Prome in 1542 served to secure the fealty of Lower Burma to the upstart regime of Tabinshwehti of Toungoo. Threatened by Bayinnaung's army of a sack of their capital Ayutthaya, the Siamese duly surrendered in 1564. When the Siamese changed their mind in 1568, the city was brutally sacked in 1569. Two hundred years later, the army's brutal sack of Pegu in 1757 secured the subsequent tribute missions of Chiang Mai, Martaban and Tavoy to Alaungpaya's court.[40] Indeed, the brutal 1767 sack of Ayutthaya has been in a major sore point in the Burmese-Thai relations to the present day.[41]

Use of firearms

editThough firearms had been introduced since the late 14th century, they became integrated into strategy only gradually over many centuries. At first, Burmese shared with other Southeast Asians a tendency to regard guns of imposing appearance as a source of spiritual power, regardless of how well they functioned. A motley assortment of local manufactures, Muslim imports, and French and English rejects defied standardized supply or training. In sharp contrast to Europe, cannon were rarely used for frontal assaults on stone fortifications.[15]

Firearms became both more common and more closely integrated into strategy from the 16th century onward when the army began to incorporate special units of gunners. Alongside Portuguese mercenaries, who formed the army's elite musketeer and artillery corps, indigenous infantry and elephant units also began using guns. By the mid-17th century, expensive foreign mercenaries had been replaced by local hereditary ahmudan corps, most of whom were descended from the foreign gunners of the previous generations. Late Toungoo and Konbaung tactics reflected the growing availability and effectiveness of firearms in three spheres:[15]

- In controlling the Irrawaddy, teak war-boats carrying up to 30 musketeers and armed with 6- or 12-pounder cannon dominated more conventional craft;

- During urban sieges, cannon mounted atop wooden platforms cleared defenders from the walls and shielded infantry attacks

- Particularly in jungle or hill terrain, Burmese infantry learned to use small arms to cover the building of stockades, which were then defended by firepower massed within.

Battlefield performance

editThe Royal Burmese Army was a major Southeast Asian armed force between the 11th and 13th centuries and between 16th and 19th centuries. It was the premier military force in the 16th century when Toungoo kings built the largest empire in the history of Southeast Asia.[25] In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the army had helped build the largest empire in mainland Southeast Asia on the back of a series of impressive military victories in the previous 70 years.[42][43] They then ran into the British in present-day northeast India. The army was defeated in all three Anglo-Burmese wars over a six-decade span (1824–1885).

Against Asian neighbors

editEven without counting its sub-par performance against European powers, the army's performance throughout history was uneven. As the main fighting force consisted of poorly trained conscripts, the performance of the army therefore greatly depended on the leadership of experienced commanders. Under poor leadership, the army could not even stop frequent Manipuri raids that terrorised northwest Burma between the 1720s and 1750s. Under good leadership, the same peasant army not only defeated Manipur (1758) but also defeated arch-rival Siam (1767) as well as much larger China (1765–1769). (A similar shift in performance too was seen in Siam. The same Siamese conscript army, having defeated in the two wars in the 1760s by the Burmese, changed its fortunes under good leadership. It stopped the Burmese in the following two decades, and built an empire by swallowing up parts of Laos and Cambodia.)

Even under good military leadership, the army's continued success was not assured because of its heavy reliance on conscript manpower. This reliance had several major weaknesses. First, the size of population was often too small to support the conqueror kings' wartime ambitions. With the size of population even under Toungoo and Konbaung empires only about 2 million, continual warfare was made possible only by gaining more territories and people for the next campaign. The strategy proved unsustainable in the long run both with Toungoo dynasty in the 1580s and 1590s and the Konbaung dynasty in the 1770s and 1780s. The long running wars of the 16th and 18th centuries greatly depopulated the Irrawaddy valley, and correspondingly reduced their later kings' ability to project power in lands most conscripts had never even heard of. The populace welcomed breaks from warfare such as during the reign of King Thalun (r. 1629–1648) or that of King Singu (r. 1776–1782).[44]

Secondly, the army never effectively solved the problems of transporting and feeding large armies, especially for the long-distance campaigns. Badly planned campaigns saw many conscripts perished even before a single shot was fired.[45] Indeed, the ability to get supplies to the front was one of the most important factors in Burma's centuries long wars with Siam in which each side's sphere of influence was largely determined by the distance and the number of days supplies could be shipped to the front.

Nonetheless, as history clearly shows, the army held more than its own against the armies of the kingdom's neighbors, all of which also faced the same problems to a similar degree. But facing head-on against more technologically advanced European forces would lead to the army's eventual end.

Against European powers

editThe Royal Burmese Army's performance vis-a-vis European forces grew worse as the technology gap grew wider. The greatest obstacle for the Burmese like with many other Southeast Asian kingdoms facing European powers was the European dominance of the seas. Aside from Arakan and Hanthawady, successive Burmese kingdoms had only riverine navies. Those navies could not challenge European ships and navies carrying troops and supplies.

Even in the matchlock era, the Burmese had difficulties facing European armies. The Burmese victory at Syriam in 1613, which drove out the Portuguese from Burma for good, came after a month's siege.[46] The technological gap was still small. According to a contemporary account by Salvador Ribeyro, a Spanish captain that served with the Portuguese recounted that the Burmese were armed similarly to the European defenders in terms of small arms. The only technological superiority that the Iberian accounts claim was only their ships.[47] In the flintlock era, mid-18th century, a small French contingent helped the Hanthawaddy garrison at Syriam hold out for 14 months before finally captured by Alaungpaya's forces in 1756.[48]

The Burmese put up the best fight in the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826), the longest and most expensive war in British Indian history. The Burmese victory at Ramu had for a short moment led to shockwaves throughout British India. The Burmese were generally more successful during inland operations but were completely outmatched against naval support in the Battles of Yangon, Danubyu and Prome. Furthermore, unlike with the French and Portuguese, the British had a strong foothold in India which allowed the British to deploy thousands of European and Indian soldiers to reinforce their initial invasion. Some 40,000 to 50,000 British troops were involved during the First War alone. The campaign cost the British five million to 13 million pounds sterling (roughly 18.5 billion to 48 billion in 2006 US dollars), and 15,000 men.[49] For the Burmese, however, it marked the gradual end of the country's independence. Not only did they lose their entire western and southern territories by the Treaty of Yandabo, a whole generation of men had been wiped out on the battlefield. Although the Burmese royal army was eventually westernized, it never managed to close the gap. After 30 years of growing technology gap, the outcome of Second Anglo-Burmese War (1852) was never in doubt. Lower Burma was lost. Another three decades later, the Third Anglo-Burmese War (1885) lasted less than a month. The entire country was gone. The remnants of the Burmese army put up a brutal guerrilla campaign against the British for the next decade. While the British were never able to establish full control of Upper Burma, they were nevertheless able to control much of the population centers and establish themselves firmly in the country.

The end

editAfter the third and final war, on 1 January 1886, the British formally abolished the millennium old Burmese monarchy and its military arm, the Royal Burmese Army. One month later, in February 1886, the former kingdom was administered as a mere province of the British Raj. (Burma would become a separate colony only in 1937.)[50] Burmese resistance went on not only in the lowland Irrawaddy valley but also in the surrounding hill regions for another 10 years until 1896.

As a result of their distrust towards the Burmese, the British enforced their rule in the province of Burma mainly with Indian troops later joined by indigenous military units of three select ethnic minorities: the Karen, the Kachin and the Chin. The Burmans, "the people who had actually conquered by fire and sword half the Southeast Asian mainland", were not allowed to enter the colonial military service.[51] (The British temporarily lifted the ban during World War I, raising a Burman battalion and seven Burman companies which served in Egypt, France and Mesopotamia. But after the war, the Burman troops were gradually discharged—most of the Burman companies were discharged between 1923 and 1925 and the last Burman company in 1929.)[52] The British used Indian and ethnic minority dominated troops to control the colony and suppress ethnic-majority dominated rebellions such as Saya San's peasant rebellion in 1930–1931. In addition to increasing the resentment of the Burman populace against the British colonial government, the recruitment policies led to tensions between the Burmans and the Karen, Kachin and Chin. The recruitment policies are also said to have rankled deeply in the Burman imagination, "eating away at their sense of pride, and turning the idea of a Burmese army into a central element of the nationalist dream".[51]

On 1 April 1937, when Burma was made a separate colony, the Burmans were allowed to join the British Burma Army, which used to be the 20th Burma Rifles of the British Indian Army. (Burmans were not allowed to enlist as officers.) At any rate, few Burmans bothered to join. Before World War II began, the British Burma Army consisted of Karen (27.8%), Chin (22.6%), Kachin (22.9%), and Burman 12.3%, without counting their British officer corps.[53]

The emergence of a nationalist anti-colonialist Japan-backed Burman-dominated army in the 1940s in turn alarmed the ethnic minorities, especially the Karen. Since independence in 1948, the Myanmar Armed Forces, still called the Tatmadaw in Burmese in honour of the army of old. But unlike the Royal Burmese Army, in which minorities played a significant role throughout history, the modern Tatmadaw has been heavily dominated by Burmans. The modern Tatmadaw has been fighting one of the world's longest running civil wars ever since.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ See (Maha Yazawin 2006: 26), (Yazawin Thit Vol. 1 2012: 236), (Hmannan Vol. 2 2012: 2) for example.

References

edit- ^ a b c Lieberman 2003: 154–156

- ^ a b Tarling 2000: 35–44

- ^ a b c d e Harvey 1925: 323–324

- ^ a b c d e Dijk 2006: 37–38

- ^ a b c d e Koenig, William (1990). The Burmese Polity, 1752-1819. Michigan: University of Michigan. pp. 105–136.

- ^ Lieberman 2003: 192–193

- ^ Lieberman 2003: 185

- ^ a b c Dijk 2006: 35–37

- ^ See formulaic reporting throughout Hmannan Yazawin, Alaungpaya Ayedawbon, and Burney 1840: 171–181 on Sino-Burmese War (1765–1769)

- ^ a b "Imperio de los Birmanes". EL Mundo Militar. 30 August 1863.

- ^ Hardiman 1901: 67

- ^ Cushman, Richard (2000). The Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya. Bangkok: Siam Society. p. 34.

- ^ a b Charney, Michael W. (2004). Southeast Asian warfare, 1300-1900. Leiden: Brill. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-4294-5269-4. OCLC 191929011.

- ^ Wilson, Horace Hayman (1827). Documents Illustrative of the Burmese War with an Introductory Sketch of the Events of the War. Calcutta: Government Gazette Press. pp. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f Lieberman 2003: 164–167

- ^ a b c d e f Heath, Ian (2003) [1998]. Armies of the Nineteenth Century: Burma and Indo-China. Foundry Books. pp. 25–30. ISBN 978-1-90154-306-3.

- ^ Pinto, Fernao Mendes (1989). The Travels of Mendes Pinto. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 317. ISBN 978-0-226-66951-9.

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 111

- ^ a b Fytche, Albert (1868). Narrative of the Mission to Mandalay in 1867. Calcutta: Foreign Department Press. p. 12.

- ^ Harvey 1925: 333–336

- ^ Lieberman 2003: 146

- ^ a b Dijk 2006: 33

- ^ Lieberman 2003: 152–153

- ^ a b c Lieberman 2003: 152

- ^ a b c Dijk 2006: 34–35

- ^ a b Tarling 2000: 41–42

- ^ Tarling 2000: 49

- ^ Harvey 1925: 242

- ^ Tarling 2000: 36

- ^ Liberman 2003: 164 and Htin Aung 1967: 198

- ^ a b Harvey 1925: 340–341

- ^ Phayre 1883: 258

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 118

- ^ Htin Aung 1967: 213

- ^ Hall 1960: Chapter XIV, p. 6

- ^ Johnston 2000: 228

- ^ Fraser-Lu 2001: 41

- ^ Harvey 1925: 124–125

- ^ See Phayre and Harvey on aforementioned wars.

- ^ Seekins 2006: 441

- ^ Liberman 2003: 32

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 107–127

- ^ Harvey 1925: 246, 262

- ^ Harvey 1925: 272–273

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 79

- ^ Adas, Michael (1989). Machines as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and Ideologies of Western Dominance. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 27.

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 94–97

- ^ Myint-U 2006: 113 and Hall 1960: Chapter XII, 43

- ^ Htin Aung 1967: 334

- ^ a b Myint-U 2006: 195

- ^ Hack, Retig 2006: 186

- ^ Steinberg 2009: 29

Bibliography

edit- Burney, Col. Henry (August 1840). Four Years' War between Burmah and China. Vol. 9. Canton: Printed for Proprietors.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Charney, Michael W. (1994). Southeast Asian Warfare 1300–1900. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004142404.

- Dijk, Wil O. (2006). Seventeenth-century Burma and the Dutch East India Company, 1634–1680 (illustrated ed.). Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789971693046.

- Fraser-Lu, Sylvia (2001). Splendour in wood: the Buddhist monasteries of Burma. Weatherhill. ISBN 9780834804937.

- Hack, Karl; Tobias Rettig (2006). Colonial armies in Southeast Asia (illustrated ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415334136.

- Hall, D.G.E. (1960). Burma (3rd ed.). Hutchinson University Library. ISBN 978-1-4067-3503-1.

- Hardiman, John Percy (1901). Sir James George Scott (ed.). Gazetteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, Part 2. Vol. 3. Yangon: Government printing, Burma.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Htin Aung, Maung (1967). A History of Burma. New York and London: Cambridge University Press.

- Johnston, William M. (2000). Encyclopedia of monasticism. Vol. 1. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781579580902.

- Kala, U (2006) [1724]. Maha Yazawin (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3 (4th printing ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Lieberman, Victor B. (2003). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80496-7.

- Maha Sithu (2012) [1798]. Myint Swe; Kyaw Win; Thein Hlaing (eds.). Yazawin Thit (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3 (2nd printing ed.). Yangon: Ya-Pyei Publishing.

- Myint-U, Thant (2006). The River of Lost Footsteps—Histories of Burma. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-16342-6.

- Phayre, Lt. Gen. Sir Arthur P. (1883). History of Burma (1967 ed.). London: Susil Gupta.

- Royal Historical Commission of Burma (2003) [1832]. Hmannan Yazawin (in Burmese). Vol. 1–3. Yangon: Ministry of Information, Myanmar.

- Seekins, Donald M. (2006). Historical dictionary of Burma (Myanmar), vol. 59 of Asian/Oceanian historical dictionaries. Vol. 59 (Illustrated ed.). Sacredcrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5476-5.

- Steinberg, David I. (2009). Burma/Myanmar: what everyone needs to know. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195390681.

- Tarling, Nicholas (2000). The Cambridge History of South-East Asia, Volume 1, Part 2 from c. 1500 to 1800 (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521663700.