Robert Southwell, SJ (c. 1561 – 21 February 1595), also Saint Robert Southwell, was an English Catholic priest of the Jesuit Order. He was also an author of Christian poetry in Elizabethan English, and a clandestine missionary in Elizabethan England.

Robert Southwell | |

|---|---|

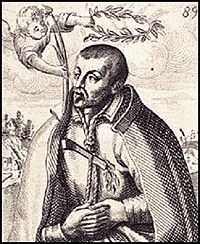

Line engraving by Matthaus Greuter (Greuther) or Paul Maupin, published 1608. | |

| Martyr | |

| Born | c. 1561 Norfolk, England |

| Died | 21 February 1595 Tyburn, London, England |

| Venerated in | Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 15 December 1929, Rome by Pope Pius XI |

| Canonized | 25 October 1970, Vatican City, by Pope Paul VI |

| Feast | 21 February |

After being arrested and imprisoned in 1592, and intermittently tortured and questioned by priest hunter Sir Richard Topcliffe, Southwell was eventually tried and convicted of high treason against Queen Elizabeth I, but in reality for refusing to take the Oath of Supremacy, renounce his belief in the independence of the English Church from control by the State, and similarly repudiate the authority of the Holy See. On 21 February 1595, Southwell was hanged at Tyburn. In 1970, he was canonised by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales.

Early life in England

editHe was born at Horsham St Faith, Norfolk, England. Southwell, the youngest of eight children, was brought up in a family of the Norfolk gentry. Despite their Catholic sympathies, the Southwells had profited considerably from King Henry VIII's Suppression of the Monasteries. Robert was the third son of Richard Southwell of Horsham St. Faith's, Norfolk, by his first wife, Bridget, daughter of Sir Roger Copley of Roughway, Sussex. The hymnodist's maternal grandmother was Elizabeth, daughter of Sir William Shelley; Sir Richard Southwell was his paternal grandfather, but his father was born out of wedlock.[1]

Enters the Society of Jesus

editIn 1576, he was sent to the English college at Douai, boarding there but studying at the Jesuit College of Anchin, a French college associated, like the English College, with the university of Douai. He studied briefly under Leonard Lessius.[1] At the end of the summer, however, his education was interrupted by the movement of French and Spanish forces. For greater safety Southwell was sent to Paris and studied at the College de Clermont under the tutelage of the Jesuit Thomas Darbyshire.[2] He returned to Douai on 15 June 1577. A year later he set off on foot to Rome with the intention of joining the Society of Jesus. A two-year novitiate at Tournai was required before joining the Society, however, and initially he was denied entry. He appealed the decision by sending a heartfelt, emotional letter to the school.[3] He bemoans the situation, writing, "How can I but wast in anguish and agony that find myself disjoined from that company, severed from that Society, disunited from that body wherein lyeth all my life my love my whole hart and affection" (Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Anglia 14, fol. 80, under date 1578).[2]

His efforts succeeded as he was admitted to the probation house of Sant' Andrea on 17 October 1578 and in 1580 became a member of the Society of Jesus.[2] Immediately after the completion of the novitiate, Southwell began studies in philosophy and theology at the Jesuit College in Rome. During this time, he worked as a secretary to the rector and writings of his are to be found among the school's documents. Upon completion of his studies, Southwell was granted his BA in 1584, which was also the year of his ordination. He was appointed "repetitor" (tutor) in the Venerable English College at Rome and after two years became the prefect of studies there.[2] It was in 1584 that an act was passed forbidding any English-born subject of Queen Elizabeth, who had entered into priests' orders in the Catholic Church since her accession, to remain in England longer than forty days on pain of death.[4]

On the English mission

editIn 1586 Southwell, at his own request, was sent to England as a Jesuit missionary with Henry Garnet.[5] He went from one Catholic family to another. The Jesuit William Weston had previously made his way to England, but he was arrested and sent to Wisbech Castle in 1587.[1] The Garnet–Southwell Jesuit English mission is considered the third;[6] the first such mission was that of Robert Parsons and Edmund Campion of 1580–1581.[7]

A spy reported to Sir Francis Walsingham the Jesuits' landing on the east coast in July, but they arrived without molestation at the house at Hackney of William Vaux, 3rd Baron Vaux of Harrowden. In 1588 Southwell and Garnet were joined by John Gerard and Edward Oldcorne. Southwell was from the outset closely watched; he mixed furtively in Protestant society under the assumed name of Cotton. He studied the terms of sport, and used them in conversation. For the most part residing in London, he made occasional excursions to Sussex and the North.[1]

In 1589 Southwell became domestic chaplain to Anne Howard, whose husband, the First Earl of Arundel, was in prison convicted of treason.[8] Arundel had been confined to the Tower of London since 1585, but his execution was postponed, and he remained in prison till his death in 1595. Southwell took up his residence with the countess at Arundel House in The Strand, London. During 1591 he occupied most of his time in writing; although Southwell's name was not publicly associated with any of his works, his literary activity was suspected by the government.[1]

Arrest and imprisonment

editAfter six years of missionary labour, Southwell was arrested at Uxendon Hall, Harrow. He was in the habit of visiting the house of Richard Bellamy who lived near Harrow and was under suspicion on account of his connection with Jerome Bellamy, who had been executed for sharing in Anthony Babington's plot. One of the daughters, Anne Bellamy, was arrested and imprisoned in the gatehouse of Holborn for being linked to the situation. Having been interrogated and raped by Richard Topcliffe, the Queen's chief priest-hunter and torturer, she revealed Southwell's movements and he was immediately arrested.[2]

He was first taken to Topcliffe's own house, adjoining the Gatehouse Prison, where Topcliffe subjected him to the torture of "the manacles". He remained silent in Topcliffe's custody for forty hours. The queen then ordered Southwell moved to the Gatehouse, where a team of Privy Council torturers went to work on him. When they proved equally unsuccessful, he was left "hurt, starving, covered with maggots and lice, to lie in his own filth". After about a month he was moved by order of the council to solitary confinement in the Tower of London. According to the early narratives, his father had petitioned the queen that his son, if guilty under the law, should so suffer, but if not should be treated as a gentleman, and that as his father he should be allowed to provide him with the necessities of life. No documentary evidence of such a petition survives, but something of the kind must have happened since his friends were able to provide him with food and clothing, and to send him the works of St. Bernard and a Bible. His superior Henry Garnet later smuggled a breviary to him. He remained in the Tower for three years, under Topcliffe's supervision.[9]

Trial and execution

editIn 1595 the Privy Council passed a resolution for Southwell's prosecution on the charges of treason. He was removed from the Tower to Newgate Prison, where he was put into a hole called Limbo.[8]

A few days later, Southwell appeared before the Lord Chief Justice, John Popham, at the bar of the King's Bench. Popham made a speech against Jesuits and seminary priests. Southwell was indicted before the jury as a traitor under the statutes prohibiting the presence, within the kingdom, of priests ordained by Rome. Southwell admitted the facts but denied that he had "entertained any designs or plots against the queen or kingdom". His only purpose, he said, in returning to England had been to administer the sacraments according to the rite of the Catholic Church to such as desired them. When asked to enter a plea, he declared himself "not guilty of any treason whatsoever", objecting to a jury being made responsible for his death but allowing that he would be tried by God and country.[2]

As the evidence was pressed, Southwell stated that he was the same age as "our Saviour". He was immediately reproved by Topcliffe for insupportable pride in making the comparison, but he said in response that he considered himself "a worm of the earth". After a brief recess, the jury returned with the predictable guilty verdict. The sentence of death was pronounced – to be hanged, drawn and quartered. He was returned through the city streets to Newgate.

On 21 February 1595, Southwell was sent to Tyburn. Execution of sentence on a notorious highwayman had been appointed for the same time, but at a different place – perhaps to draw the crowds away – and yet many came to witness Southwell's death. Having been dragged through the streets on a sledge, he stood in the cart beneath the gibbet and made the sign of the cross with his pinioned hands before reciting a passage from the Christians' scriptures' Romans chapter 14. The sheriff made to interrupt him; but he was allowed to address the people at some length, confessing that he was a Jesuit priest and praying for the salvation of Queen and country. As the cart was drawn away, he commended his soul to God with the words of the psalm in manus tuas. He hung in the noose for a brief time, making the sign of the cross as best he could. As the executioner made to cut him down, in preparation for disembowelling him while still alive, Lord Mountjoy and some other onlookers tugged at his legs to hasten his death. His lifeless body was then disembowelled and quartered.[10] As his severed head was displayed to the crowd, no one shouted the traditional "Traitor!".

Works and legacy

editSouthwell addressed his Epistle of Comfort to Philip, Earl of Arundel.[11] This and other of his religious tracts, A Short Rule of Good Life, Triumphs over Death, and a Humble Supplication to Queen Elizabeth, circulated in manuscript. Mary Magdalen's Funeral Tears was openly published in 1591. It proved to be very popular, going through ten editions by 1636. Thomas Nashe's imitation of Mary Magdalen's Funeral Tears in Christ's Tears over Jerusalem proves that the works received recognition outside of Catholic circles.[5]

Soon after Southwell's death, St Peter's Complaint with other poems appeared, printed by John Windet for John Wolfe, but without the author's name. A second edition, including eight more poems, appeared almost immediately. Then on 5 April, John Cawood, the publisher of Mary Magdalen's Funeral Tears, who probably owned the copyright all along, entered the book in the Stationers' Register, and brought out a third edition. Saint Peter's Complaint proved even more popular than Mary Magdalen's Funeral Tears; it went into fourteen editions by 1636. Later that same year, another publisher, John Busby, having acquired a manuscript of Southwell's collection of lyric poems, brought out a little book containing a further twenty-two poems, under the title Maeoniae. When in 1602 Cawood added another eight poems to his book, the English publication of Southwell's works came to an end. Southwell's Of the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar, unpublishable in England, appeared in a broadsheet published at Douai in 1606. A Foure fould Meditation of the foure last things, formerly attributed to Southwell, is by Philip Earl of Arundel. Similarly, the prose A Hundred Meditations of the Love of God, once thought to be an original work by Southwell, is now known to be his literary translation of Fray Diego de Estella's Meditaciones devotisimas del amor de Dios.[12]

Much of Southwell's literary legacy rests on his considerable influence on other writers. There is evidence of Shakespeare's allusions to Southwell's work, particularly in The Merchant of Venice, Romeo & Juliet, Hamlet, and King Lear. Southwell's influence can be seen in the work of Donne, Herbert, Crashaw and Hopkins.[13]

A memoir of Southwell was drawn up soon after his death. Much of the material was incorporated by Richard Challoner in his Memoirs of Missionary Priests (1741), and the manuscript is now in the Public Record Office in Brussels. See also Alexis Possoz, Vie du Pre R. Southwell (1866); and a life in Henry Foley's Records of the English Province of the Society of Jesus: historic facts illustrative of the labours and sufferings of its members in the 16th and 17th centuries, 1877 (i. 301387). Foley's narrative includes copies of documents connected with his trial, and gives information on the original sources.[5] The standard modern life, however, is Christopher Devlin's The Life of Robert Southwell, Poet and Martyr, London, 1956.

As the prefatory letter to his poems "The Author to his Loving Cousin" implies, Southwell seems to have composed with a musical setting in mind. One such contemporary setting survives, Thomas Morley's provision of music for stanzas from "Mary Magdalen's Complaint at Christ's Death" in his First book of ayres (1600). Elizabeth Grymeston, in a book published for her son (1604), described how she sang stanzas from Saint Peter's Complaint as part of her daily prayer. The best-known modern setting of Southwell's words is Benjamin Britten's use of stanzas from "New Heaven, New War" and "New Prince, New Pomp", two of the pieces in his Ceremony of Carols (1942).

In the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, Southwell and his companion and associate Henry Garnet were noted for their allegiance to the doctrine of mental reservation, a controversial ethical concept of the period.[5]

Under Southwell's Latinised name, Sotvellus, and in his memory, the English Jesuit Nathaniel Bacon, Secretary of the Society of Jesus, published the updated third edition of the Bibliotheca Scriptorum Societatis Iesu (Rome, 1676). This Jesuit bibliography containing more than 8000 authors made "Sotvel" a common reference.[14]

Southwell was beatified in 1929 and canonised by Pope Paul VI as one of the Forty Martyrs of England and Wales on 25 October 1970.[5]

Southwell is also the patron saint of Southwell House, a house in the London Oratory School in Fulham, London.[5]

Critical views

editIn the view of the critic Helen C. White, probably no work of Southwell's is more "representative of his Baroque genius than the prose Marie Magdalens Funeral Teares, published late in 1591, close to the end of his career. The very choice of this subject would seem the epitome of the Baroque; for it is a commonplace that the penitent Magdalen, with her combination of past sensuality and current remorsefulness, was a favourite object of contemplation to the Counter-Reformation."[15]

Southwell's poetry is largely addressed to an English Catholic community under siege in post-Reformation Elizabethan England.[16] Southwell endeavoured to convince remaining English Catholics that religious persecution by the State represented an opportunity for spiritual growth. In his view, martyrdom was one of the most sincere forms of religious devotion. Southwell's poem "Life is but Losse" is an example of this concern. Throughout the seven stanzas, Southwell describes the martyrdom of English Catholics at the time, employing biblical figures of both Testaments (Samson and the Apostles). The poem's title forewarns the reader of the pessimistic tone Southwell uses to describe life, as in the line "Life is but losse, where death is deemed gaine." Being next to God is the perfect way to achieve spiritual bliss: "To him I live, for him I hope to dye" is Southwell's manner of informing the reader of the reason for his existence, which does not end with death.[17]

Southwell's writing differs from that of the Neostoics of his time and the negative Stoic view of the passions in his belief in the creative value of passion. Some of Southwell's contemporaries were also defenders of passion, but he was very selective when it came to where passions were directed. He was quoted as saying, "Passions I allow, and loves I approve, only I would wish that men would alter their object and better their intent". He felt that he could use his writing to stir religious feelings, and it is this pattern in his writing that has caused scholars to declare him a leading Baroque writer.

Pierre Janelle published a study on Southwell in 1935 in which he recognized him as a pioneer Baroque figure, one of the first Baroque writers of the late 16th century and influential on numerous Baroque writers of the 17th century.[18]

Ben Jonson remarked to Drummond of Hawthornden that "so he had written that piece of [Southwell's], 'The Burning Babe', he would have been content to destroy many of his."[19] In fact, there is a strong case to be made for Southwell's influence on his contemporaries and successors, among them Drayton, Lodge, Nashe, Herbert, Crashaw, and especially William Shakespeare, who seems to have known his work, both poetry and prose, extremely well.[20]

More recently, the posthumously published 1873 first edition of Southwell's literary translation into Elizabethan English of Fray Diego de Estella's Meditaciónes devotíssimas del amor de Dios ("A Hundred Meditations on the Love of God") helped inspire Fr. Gerard Manley Hopkins to write the poem The Windhover.[21]

Quotations

edit- "The Chief Justice asked how old he was, seeming to scorn his youth. He answered that he was near about the age of our Saviour, Who lived upon the earth thirty-three years; and he himself was as he thought near about thirty-four years. Hereat Topcliffe seemed to make great acclamation, saying that he compared himself to Christ. Father Southwell answered, 'No he was a humble worm created by Christ.' 'Yes,' said Topcliffe, 'you are Christ's fellow.'"—Father Henry Garnet, "Account of the Trial of Robert Southwell," quoted in Caraman's The Other Face, page 230.

- Southwell: I am decayed in memory with long and close imprisonment, and I have been tortured ten times. I had rather have endured ten executions. I speak not this for myself, but for others; that they may not be handled so inhumanely, to drive men to desperation, if it were possible.

Topcliffe: If he were racked, let me die for it.

Southwell: No; but it was as evil a torture, or late device.

Topcliffe: I did but set him against a wall.

Southwell: Thou art a bad man.

Topcliffe: I would blow you all to dust if I could.

Southwell: What, all?

Topcliffe: Ay, all.

Southwell: What, soul and body too? At his Trial Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine - "Not where I breathe, but where I love, I live" on the outside of The DeNaples Center at the Jesuit University of Scranton. Longer version: "Not where I breathe, but where I love, I live; / Not where I love, but where I am, I die."

- "Hoist up saile while gale doth last, Tide and wind stay no man's pleasure."—from "St. Peter's Complaint. 1595"[5]

- "May never was the month of love, For May is full of flowers; But rather April, wet by kind, For love is full of showers."—from "Love's Servile Lot"[5]

- "My mind to me an empire is, While grace affordeth health."—from "Look Home"[5]

- "O dying souls, behold your living spring; O dazzled eyes, behold your sun of grace; Dull ears, attend what word this Word doth bring; Up, heavy hearts, with joy your joy embrace. From death, from dark, from deafness, from despair: This life, this light, this Word, this joy repairs."—from "The Nativity of Christ"[5]

- "A poet, a lover and a liar are by many reckoned but three words with one signification." – from "The author to his loving cousin," published with "St. Peter's Complaint." 1595.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Nancy P. Southwell, Robert [St Robert Southwell] (1561–1595), writer, Jesuit, and martyr Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Southwell, Robert". 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ^ Pollard, Albert Frederick (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 09 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 466–587, see p 517 & p 531.

VII. The Reformation and the Age of Elizabeth (1528–1603)...

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jokinen, Anniina. The Works of Robert Southwell 9 October 1997. 26 September 2008.

- ^ David Colclough (2003). John Donne's professional lives. DS Brewer. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-85991-775-9.

- ^ Waterfield John Waterfield (2009). The Heart of His Mystery: Shakespeare and the Catholic Faith in England Under Elizabeth and James. iUniverse. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4401-4343-4.

- ^ a b "Robert Southwell (c. 1561–1595)". 2003. MasterFILE Premier

- ^ Brownlow, F.W. Robert Southwell. Twayne Publishers, 1996, p. 15.

- ^ Thurston, Herbert. "Venerable Robert Southwell." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912

- ^ Robert S. Miola (ed.). Early Modern Catholicism. An anthology of primary sources. Oxford: University Press, 2007, pp. 301 f.

- ^ Gary M. Bouchard (2018), Southwell's Sphere: The Influence of England's Secret Poet, St. Augustine's Press. Pages 187-210.

- ^ Gary M. Bouchard, Southwell's Sphere, St. Augustine's Press, 2017

- ^ Google Books, listed under Nathaniel Southwell

- ^ White, Helen C. "Southwell: Metaphysical and Baroque", Modern Philology, Vol. 61, No. 3 (February 1964): 159–168.

- ^ Robert S. Miola (ed.). Early Modern Catholicism. An anthology of primary sources. Oxford: University Press, 2007, with excerpts pp. 26, 32 -34, 192–204, 278–80, 301–2.

- ^ Antonio S. Oliver. "Southwell and His Idea of Death as a Divine Honor." 9 Oct 1997. 26 Sep 2008 [1]

- ^ Pierre Janelle. Robert Southwell, The Writer: A Study in Religious Inspiration (Mamaroneck, NY: Paul P. Appel, 1971). Louis Martz also discusses Southwell's relation to later English devotional poetry in his study The Poetry of Meditation: A Study in English Religious Literature of the Seventeenth Century (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954).

- ^ Ben Jonson. Works. Ed. C. H. Herford and Percy Simpson. 11 Vols. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1925–52, 1.137.

- ^ Brownlow, pp.93–6, 125. Also John Klause. Shakespeare, the Earl and the Jesuit. Madison & Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2008, passim.

- ^ Gary M. Bouchard (2018), Southwell's Sphere: The Influence of England's Secret Poet, St. Augustine's Press. Pages 187-210.

Works cited

edit- Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, Anglia 14, fol. 80, under date 1578

- Bishop Challoner. Memoirs of Missionary Priests and other Catholics of both sexes that have Suffered Death in England on Religious Accounts from the year 1577 to 1684 (Manchester, 1803) vol. I, p. 175ff.

- Brown, Nancy P. Southwell, Robert [St Robert Southwell] (1561–1595), writer, Jesuit, and martyr Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. Southwell, Robert. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Janelle, Pierre. Robert Southwell, The Writer: A Study in Religious Inspiration. Mamaroneck, NY: Paul P. Appel, 1971.

- Jokinen, Anniina. The Works of Robert Southwell. 9 Oct 1997. 26 Sep 2008.

- "Robert Southwell (c. 1561–1595)". 2003. MasterFILE Premier

- F.W.Brownlow. Robert Southwell. Twayne Publishers, 1996.

- John Klause. Shakespeare, the Earl, and the Jesuit. Madison & Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2008.

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Southwell, Robert". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 517–518.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Southwell, Robert (1561?–1595)". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

See also

editFurther reading

edit- Louis Martz. The Poetry of Meditation: A Study in English Religious Literature of the Seventeenth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954. ISBN 0-300-00165-7

- Scott R. Pilarz. Robert Southwell, and the Mission of Literature, 1561–1595: Writing Reconciliation. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004. ISBN 0-7546-3380-2

- Robert Southwell, Hořící dítě a jiné básně, Josef Hrdlička (translat.), Refugium, Olomouc 2008.

- St. Robert Southwell: Collected Poems. Ed. Peter Davidson and Anne Sweeney. Manchester: Carcanet Press, 2007. ISBN 1-85754-898-1

- Ceri Sullivan, Dismembered Rhetoric. English Recusant Writing, 1580–1603. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1995. ISBN 0-8386-3577-6

- Anne Sweeney, Robert Southwell. Snow in Arcadia: Redrawing the English Lyric Landscape, 1586–95. Manchester University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-7190-7418-5

- George Whalley, "The Life and Martyrdom of Robert Southwell." Radio Script. 135-minute dramatic feature. CBC Radio Tuesday Night 29 June 1971. Produced by John Reeves.

External links

edit- The Cambridge History of English and American Literature

- The Poems of Robert Southwell

- Complete Poems of Robert Southwell, Grosart edition, 1872.

- The complete works of R. Southwell : with life and death (1876)

- A foure-fould meditation, of the foure last things (1895)

- The prose works of Robert Southwell. Ed. by W.J. Walter (1828)

- Works by or about Robert Southwell at the Internet Archive

- Works by Robert Southwell at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)