Reserpine is a drug that is used for the treatment of high blood pressure, usually in combination with a thiazide diuretic or vasodilator.[1] Large clinical trials have shown that combined treatment with reserpine plus a thiazide diuretic reduces mortality of people with hypertension. Although the use of reserpine as a solo drug has declined since it was first approved by the FDA in 1955,[2] the combined use of reserpine and a thiazide diuretic or vasodilator is still recommended in patients who do not achieve adequate lowering of blood pressure with first-line drug treatment alone.[3][4][5] The reserpine-hydrochlorothiazide combo pill was the 17th most commonly prescribed of the 43 combination antihypertensive pills available in 2012.[6]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Serpasil, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Consumer Drug Information |

| MedlinePlus | a601107 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 50% |

| Metabolism | gut/liver |

| Elimination half-life | phase 1 = 4.5h, phase 2 = 271h, average = 33h |

| Excretion | 62% feces / 8% urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.044 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

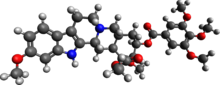

| Formula | C33H40N2O9 |

| Molar mass | 608.688 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

The antihypertensive actions of reserpine are largely due to its antinoradrenergic effects, which are a result of its ability to deplete catecholamines (among other monoamine neurotransmitters) from peripheral sympathetic nerve endings. These substances are normally involved in controlling heart rate, force of cardiac contraction and peripheral vascular resistance.[7]

At doses of 0.05 to 0.2 mg per day, reserpine is well tolerated;[8] the most common adverse effect being nasal stuffiness.

Reserpine has also been used for relief of psychotic symptoms.[9] A review found that in persons with schizophrenia, reserpine and chlorpromazine had similar rates of adverse effects, but that reserpine was less effective than chlorpromazine for improving a person's global state.[10]

Medical uses

editReserpine is recommended as an alternative drug for treating hypertension by the JNC 8.[11] A 2016 Cochrane review found reserpine to be as effective as other first-line antihypertensive drugs for lowering of blood pressure.[12] The reserpine–thiazide diuretic combination is one of the few drug treatments shown to reduce mortality in randomized controlled trials: The Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program,[13] the Veterans Administration Cooperative Study Group in Anti-hypertensive Agents,[14] and the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program.[15] Moreover, reserpine was included as a secondary antihypertensive option for patients who did not achieve blood pressure lowering targets in the ALLHAT study.[16]

It was previously used to treat symptoms of dyskinesia in patients with Huntington's disease,[17] but alternative medications are preferred today.[18]

The daily dose of reserpine in antihypertensive treatment is as low as 0.05 to 0.25 mg. The use of reserpine as an antipsychotic drug had been nearly completely abandoned, but more recently it made a comeback as adjunctive treatment, in combination with other antipsychotics, so that more refractory patients get dopamine blockade from the other antipsychotic, and dopamine depletion from reserpine. Doses for this kind of adjunctive goal can be kept low, resulting in better tolerability. Originally, doses of 0.5 mg to 40 mg daily were used to treat psychotic diseases.

Doses in excess of 3 mg daily often required use of an anticholinergic drug to combat excessive cholinergic activity in many parts of the body as well as parkinsonism. For adjunctive treatment, doses are typically kept at or below 0.25 mg twice a day.

Adverse effects

editAt doses of less than 0.2 mg/day, reserpine has few adverse effects, the most common of which is nasal congestion.[19]

Reserpine can cause: nasal congestion, nausea, vomiting, weight gain, gastric intolerance, gastric ulceration (due to increased cholinergic activity in gastric tissue and impaired mucosal quality), stomach cramps and diarrhea. The drug causes hypotension and bradycardia and may worsen asthma. Congested nose and erectile dysfunction are other consequences of alpha-blockade.[20]

Central nervous system effects at higher doses (0.5 mg or higher) include drowsiness, dizziness, nightmares, Parkinsonism, general weakness and fatigue. [21]

High dose studies in rodents found reserpine to cause fibroadenoma of the breast and malignant tumors of the seminal vesicles among others. Early suggestions that reserpine causes breast cancer in women (risk approximately doubled) were not confirmed. It may also cause hyperprolactinemia.[20]

Reserpine passes into breast milk and is harmful to breast-fed infants, and should therefore be avoided during breastfeeding if possible.[22]

It may produce an excessive decline in blood pressure at doses needed for treatment of anxiety, depression, or psychosis.[23]

Mechanism of action

editReserpine irreversibly blocks the H+-coupled vesicular monoamine transporters, VMAT1 and VMAT2. VMAT1 is mostly expressed in neuroendocrine cells. VMAT2 is mostly expressed in neurons. Thus, it is the blockade of neuronal VMAT2 by reserpine that inhibits uptake and reduces stores of the monoamine neurotransmitters norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin and histamine in the synaptic vesicles of neurons.[24] VMAT2 normally transports free intracellular norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine in the presynaptic nerve terminal into presynaptic vesicles for subsequent release into the synaptic cleft ("exocytosis"). Unprotected neurotransmitters are metabolized by MAO (as well as by COMT), attached to the outer membrane of the mitochondria in the cytosol of the axon terminals, and consequently never excite the post-synaptic cell. Thus, reserpine increases removal of monoamine neurotransmitters from neurons, decreasing the size of the neurotransmitter pools, and thereby decreasing the amplitude of neurotransmitter release.[25] As it may take the body days to weeks to replenish the depleted VMATs, reserpine's effects are long-lasting.[26]

Biosynthetic pathway

editReserpine is one of dozens of indole alkaloids isolated from the plant Rauvolfia serpentina.[27] In the Rauvolfia plant, tryptophan is the starting material in the biosynthetic pathway of reserpine, and is converted to tryptamine by tryptophan decarboxylase enzyme. Tryptamine is combined with secologanin in the presence of strictosidine synthetase enzyme and yields strictosidine. Various enzymatic conversion reactions lead to the synthesis of reserpine from strictosidine.[28]

History

editReserpine was isolated in 1952 from the dried root of Rauvolfia serpentina (Indian snakeroot),[29] which had been known as Sarpagandha and had been used for centuries in India for the treatment of insanity, as well as fever and snakebites[30] — Mahatma Gandhi used it as a tranquilizer.[31] It was first used in the United States by Robert Wallace Wilkins in 1950. Its molecular structure was elucidated in 1953 and natural configuration published in 1955.[32] It was introduced in 1954, two years after chlorpromazine.[33] The first total synthesis was accomplished by R. B. Woodward in 1958.[32]

Reserpine was influential in promoting the thought of a biogenic amine hypothesis of depression.[34][35] Reserpine-induced depletion of monoamine neurotransmitters in the synapse allegedly caused depression and was cited as evidence that a "chemical imbalance", namely low levels of monoamine neurotransmitters, is what causes clinical depression in humans. A 2003 review showed barely any evidence that reserpine actually causes depression in either human patients or animal models.[36] Notably, reserpine was the first compound ever to be shown to be an effective antidepressant in a randomized placebo-controlled trial.[37][38] A 2022 systematic review found that studies of the influence of reserpine on mood were highly inconsistent, with similar proportions of studies reporting depressogenic effects, no influence on mood, and antidepressant effects.[39] The quality of evidence was limited, and only a subset of studies were randomized controlled trials.[39] Although reserpine itself cannot provide good evidence for the monoamine hypothesis of depression, other lines of evidence support the idea that boosting serotonin or norepinephrine can effectively treat depression, as shown by SSRIs, SNRIs, and tricyclic antidepressants.

Veterinary use

editReserpine is used as a long-acting tranquilizer to subdue excitable or difficult horses and has been used illicitly for the sedation of show horses, for-sale horses, and in other circumstances where a "quieter" horse might be desired.[40]

It is also used in dart guns.

Research

editAnimal model of depression and amotivation

editSimilarly to tetrabenazine, reserpine, via depletion of monoamine neurotransmitters, produces depression-like effects and lack of motivation or fatigue-like symptoms in animals.[41][42] This can be useful in evaluating new antidepressants and psychostimulant-like agents.[41][42]

Antibacterial effects

editReserpine inhibits formation of biofilms by Staphylococcus aureus and inhibits the metabolic activity of bacteria present in biofilms.[43]

References

edit- ^ Tsioufis C, Thomopoulos C (November 2017). "Combination drug treatment in hypertension". Pharmacological Research. 125 (Pt B): 266–271. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2017.09.011. PMID 28939201. S2CID 32904492.

- ^ "Reserpine".

- ^ James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. (February 2014). "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.

- ^ Weir MR (August 2020). "Reserpine: A New Consideration of and Old Drug for Refractory Hypertension". American Journal of Hypertension. 33 (8): 708–710. doi:10.1093/ajh/hpaa069. PMC 7402223. PMID 32303749.

- ^ Barzilay J, Grimm R, Cushman W, Bertoni AG, Basile J (August 2007). "Getting to goal blood pressure: why reserpine deserves a second look". Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 9 (8): 591–4. doi:10.1111/j.1524-6175.2007.07229.x. PMC 8110058. PMID 17673879.

- ^ Wang B, Choudhry NK, Gagne JJ, Landon J, Kesselheim AS (March 2015). "Availability and utilization of cardiovascular fixed-dose combination drugs in the United States". American Heart Journal. 169 (3): 379–386.e1. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2014.12.014. PMID 25728728.

- ^ Forney, Barbara. Reserpine for Veterinary Use Wedgewood Pharmacy. 2001-2002.

- ^ Morley JE (May 2014). "Treatment of hypertension in older persons: what is the evidence?". Drugs & Aging. 31 (5): 331–7. doi:10.1007/s40266-014-0171-7. PMID 24668034. S2CID 207489850.

- ^ Hoenders HJ, Bartels-Velthuis AA, Vollbehr NK, Bruggeman R, Knegtering H, de Jong JT (February 2018). "Natural Medicines for Psychotic Disorders: A Systematic Review". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 206 (2): 81–101. doi:10.1097/NMD.0000000000000782. PMC 5794244. PMID 29373456.

- ^ Nur S, Adams CE (April 2016). "Chlorpromazine versus reserpine for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (4): CD012122. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012122.pub2. PMC 10350329. PMID 27124109.

- ^ James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. (February 2014). "2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8)". JAMA. 311 (5): 507–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.284427. PMID 24352797.

- ^ Shamon SD, Perez MI (December 2016). "Blood pressure-lowering efficacy of reserpine for primary hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (12): CD007655. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007655.pub3. PMC 6464022. PMID 27997978.

- ^ "Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group". JAMA. 242 (23): 2562–71. December 1979. doi:10.1001/jama.242.23.2562. PMID 490882. full text at OVID

- ^ "Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressures averaging 115 through 129 mm Hg". JAMA. 202 (11): 1028–34. December 1967. doi:10.1001/jama.202.11.1028. PMID 4862069.

- ^ "Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). SHEP Cooperative Research Group". JAMA. 265 (24): 3255–64. June 1991. doi:10.1001/jama.265.24.3255. PMID 2046107.

- ^ ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (December 2002). "Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)". JAMA. 288 (23): 2981–97. doi:10.1001/jama.288.23.2981. PMID 12479763. Archived from the original on November 26, 2009.

- ^ Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-59541-101-3.

- ^ Thanvi B, Lo N, Robinson T (June 2007). "Levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease: clinical features, pathogenesis, prevention and treatment". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 83 (980): 384–8. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2006.054759. PMC 2600052. PMID 17551069.

- ^ Curb JD, Schneider K, Taylor JO, Maxwell M, Shulman N (March 1988). "Antihypertensive drug side effects in the Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program". Hypertension. 11 (3 Pt 2): II51-5. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.11.3_pt_2.ii51. PMID 3350594.

- ^ a b AJ Giannini, HR Black. Psychiatric, Psychogenic, and Somatopsychic Disorders Handbook. Garden City, NY. Medical Examination Publishing, 1978. Pg. 233. ISBN 0-87488-596-5.

- ^ Barcelos RC, Benvegnú DM, Boufleur N, Pase C, Teixeira AM, Reckziegel P, et al. (February 2011). "Short term dietary fish oil supplementation improves motor deficiencies related to reserpine-induced parkinsonism in rats". Lipids. 46 (2): 143–9. doi:10.1007/s11745-010-3514-0. PMID 21161603. S2CID 4036935.

- ^ kidsgrowth.org Drugs and Other Substances in Breast Milk Archived 2007-06-23 at archive.today Retrieved on June 19, 2009

- ^ Pinel JP (2011). Biopsychology (8th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. p. 469. ISBN 978-0-205-83256-9.

- ^ Yaffe D, Forrest LR, Schuldiner S (May 2018). "The ins and outs of vesicular monoamine transporters". The Journal of General Physiology. 150 (5): 671–682. doi:10.1085/jgp.201711980. PMC 5940252. PMID 29666153.

- ^ Eiden LE, Weihe E (January 2011). "VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1216 (1): 86–98. Bibcode:2011NYASA1216...86E. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMC 4183197. PMID 21272013.

- ^ German CL, Baladi MG, McFadden LM, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE (October 2015). "Regulation of the Dopamine and Vesicular Monoamine Transporters: Pharmacological Targets and Implications for Disease". Pharmacological Reviews. 67 (4): 1005–24. doi:10.1124/pr.114.010397. PMC 4630566. PMID 26408528.

- ^ "Indole Alkaloids" Archived 2011-09-02 at the Wayback Machine Major Types Of Chemical Compounds In Plants & Animals Part II: Phenolic Compounds, Glycosides & Alkaloids. Wayne's Word: An On-Line Textbook of Natural History. 2005.

- ^ Ramawat et al, 1999.Ramawat KG, Sharma R, Suri SS (2007-01-01). Ramawat KG, Merillon JM (eds.). Medicinal Plants in Biotechnology- Secondary metabolites 2nd edition 2007. Oxford and IBH, India. pp. 66–367. ISBN 978-1-57808-428-9.

- ^ Rauwolfia Dorlands Medical Dictionary. Merck Source. 2002.

- ^ "Reserpine". The Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth ed.). Columbia University Press. 2005. Archived from the original on 2009-02-12.

- ^ Pills for Mental Illness?, TIME Magazine, November 8, 1954

- ^ a b Nicolaou KC, Sorensen EJ (1996). Classics in Total Synthesis. Weinheim, Germany: VCH. p. 55. ISBN 978-3-527-29284-4.

- ^ López-Muñoz F, Bhatara VS, Alamo C, Cuenca E (2004). "[Historical approach to reserpine discovery and its introduction in psychiatry]". Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría. 32 (6): 387–95. PMID 15529229.

- ^ Everett GM, Toman JE (1959). "Mode of action of Rauwolfia alkaloids and motor activity". Biol Psychiat. 2: 75–81.

- ^ Govindarajulu M (2021). "Reserpine-Induced Depression and Other Neurotoxicity: A Monoaminergic Hypothesis.". In Agrawal D (ed.). Medicinal herbs and fungi : neurotoxicity vs. neuroprotection. Singapore: Springer. ISBN 978-981-334-140-1.

- ^ Baumeister AA, Hawkins MF, Uzelac SM (June 2003). "The myth of reserpine-induced depression: role in the historical development of the monoamine hypothesis". Journal of the History of the Neurosciences. 12 (2): 207–20. doi:10.1076/jhin.12.2.207.15535. PMID 12953623. S2CID 42407412.

- ^ Davies DL, Shepherd M (July 1955). "Reserpine in the treatment of anxious and depressed patients". Lancet. 269 (6881): 117–20. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(55)92118-8. PMID 14392947.

- ^ Healy, David (1997). The Antidepressant Era. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03958-2.

- ^ a b Strawbridge R, Javed RR, Cave J, Jauhar S, Young AH (August 2022). "The effects of reserpine on depression: A systematic review". J Psychopharmacol. 37 (3): 248–260. doi:10.1177/02698811221115762. PMC 10076328. PMID 36000248. S2CID 251765916.

- ^ Forney B. Reserpine for veterinary use. Available at http://www.wedgewoodpetrx.com/learning-center/professional-monographs/reserpine-for-veterinary-use.html.

- ^ a b Stutz PV, Golani LK, Witkin JM (February 2019). "Animal models of fatigue in major depressive disorder". Physiol Behav. 199: 300–305. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2018.11.042. PMID 30513290.

In a study performed by Sommer et al. (2014), healthy rats treated with the selective dopamine transport (DAT) inhibitor MRZ-9547 (Fig. 1) chose high effort, high reward more often than their untreated matched controls.

- ^ a b Salamone JD, Yohn SE, López-Cruz L, San Miguel N, Correa M (May 2016). "Activational and effort-related aspects of motivation: neural mechanisms and implications for psychopathology". Brain. 139 (Pt 5): 1325–1347. doi:10.1093/brain/aww050. PMC 5839596. PMID 27189581.

Several recent studies have focused on the effort-related effects of [tetrabenazine (TBZ)]. TBZ inhibits VMAT-2 (i.e. vesicular monoamine transporter type 2, encoded by Slc18a2), which results in reduced vesicular storage and depletion of monoamines. The greatest effects of TBZ at low doses have been reported to be on dopamine in the striatal complex, which is substantially depleted relative to norepinephrine and 5- HT (Pettibone et al., 1984; Tanra et al., 1995). Originally developed as a reserpine-type antipsychotic, TBZ has been approved for use as a treatment for Huntington's disease and other movement disorders, but its major side effects include depressive symptoms (Frank, 2009, 2010; Guay, 2010; Chen et al., 2012). Like reserpine, TBZ has been used in studies involving classical animal models of depression (Preskorn et al., 1984; Kent et al., 1986; Wang et al., 2010). Low doses of TBZ that decreased accumbens dopamine release and dopamine-related signal transduction altered effort-related choice behaviour as assessed by concurrent lever pressing/chow feeding choice procedures (Nunes et al., 2013b; Randall et al., 2014).

- ^ Parai D, Banerjee M, Dey P, Mukherjee SK (January 2020). "Reserpine attenuates biofilm formation and virulence of Staphylococcus aureus". Microbial Pathogenesis. 138: 103790. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103790. PMID 31605761.

External links

edit- NLM Hazardous Substances Databank – Reserpine

- PubChem Substance Summary: Reserpine National Center for Biotechnology Information.

- The Stork Synthesis of (−)-Reserpine