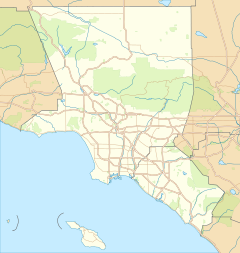

The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library is the presidential library and burial site of Ronald Reagan, the 40th president of the United States (1981–1989), and his wife Nancy Reagan. Located in Simi Valley, California, the library is administered by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

| Ronald Reagan Presidential Library | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Location | Simi Valley, California, United States |

| Coordinates | 34°15′34″N 118°49′10″W / 34.2595°N 118.8194°W |

| Named for | Ronald Reagan |

| Construction started | November 21, 1988 |

| Completed | November 4, 1991 |

| Cost | $60 million USD |

| Management | National Archives and Records Administration Reagan Library Foundation |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 243,000 square feet (22,600 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Hugh Stubbins |

| Website | |

| www | |

The library opened in 1991 and houses the repository of presidential records from the Reagan administration. The library contains millions of documents, photographs, films and tapes. It also contains memorabilia and a permanent exhibit of Ronald Reagan's life.

Planning

editThe first person to propose a site for the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library was W. Glenn Campbell, director of the Hoover Institution, a conservative think tank much used by Reagan for policy positions. Campbell contacted Ronald Reagan in February 1981 to say that the Hoover Institution was willing to host the Reagan Library at their headquarters on the campus of Stanford University in Northern California. The advantage held by Hoover was that Reagan was an honorary fellow, and Hoover already housed Reagan's papers from his campaign for and transition to governor of California. Ronald and Nancy Reagan participated in occasional informal discussions about the library plans with Campbell and Stanford President Donald Kennedy through 1982. During this time, a proposal to place the Richard Nixon Presidential Library on campus at Duke University in North Carolina was under attack by Duke faculty and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) who were all worried that the Richard Nixon Foundation would not allow scholarly access to archives, which they judged was the primary purpose of a presidential library. The Duke faculty were also firmly against having a museum serve as a memorial to Nixon who had left office in disgrace. This public controversy shaped the discussions about a Reagan Library at Stanford.[1] Reagan hosted the Hoover Institution at the White House in January 1982, telling them, "You built the knowledge base that made the changes now taking place in Washington possible."[2]

Reagan formally accepted the Hoover Institution invitation in January 1983. The plans included three components: an archival library for researchers, a museum for the general public, and a "Center for Public Affairs" which would serve as a think tank to promote the ideas of the Reagan Foundation. Negotiations were undertaken between Stanford's Kennedy and Reagan's adviser Edwin Meese. In June 1983, Kennedy called for Stanford faculty to express their opinions through the Rosse Committee, to report by October.[1] Professor John Manley accused the Hoover Institution of right-wing bias, and said that Stanford's reputation for objectivity would suffer from partisanship.[2] The Rosse Committee reported both the negative and the positive aspects of the proposed library, and Stanford's Board of Trustees approved the location in December 1983.[1] The agreement was announced in February 1984.[3][4] Local opposition heightened after that, and a student group was formed to publicize the negative aspects, shocking their readers with fearful images of scholarly Stanford turning into a political "Reagan University". This polarized response was compared in the press to the Nixon Foundation's difficulties at Duke. A recurring point of contention was the Center for Public Affairs; some critics announced they would only approve the project if the think tank was removed or relocated offsite. Nancy Reagan insisted that the three components were indivisible, that she would not consider any suggestion of splitting up the proposal.[1]

Because of continued concerns about partisan politics, the library plans were canceled by Stanford in 1987.[5] The site in Simi Valley was chosen the same year.[6]

Design

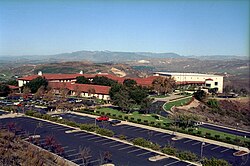

editThe Reagan Library is located at 40 Presidential Drive in Simi Valley, California[7] about 40 miles (64 km) northwest of downtown Los Angeles and 15 miles (24 km) west of Chatsworth.[citation needed]

The library's design was unveiled on January 28, 1987,[8] in Spanish Mission style.[9] According to its architect, Hugh Stubbins, Reagan approved the design, likening it to his residence of Rancho del Cielo.[8]

New York design agency Donovan/Green was contracted to design the facility's interior and exhibition spaces with partner Nancye Green overseeing the project.[10][11] Construction of the library began in 1988, and the center was dedicated on November 4, 1991.[12][13] The dedication ceremonies were the first time in United States history that five American presidents gathered together in the same place: Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan himself, and George H. W. Bush.[14] Six First Ladies also attended: Lady Bird Johnson, Pat Nixon, Betty Ford, Rosalynn Carter, Nancy Reagan, and Barbara Bush.[15]

Facilities and management

editAs a presidential library administered by the NARA, the Reagan Library, under the authority of the Presidential Records Act, is the repository of presidential records for the Reagan administration.[16] Holdings include 50 million pages of presidential documents, over 1.6 million photographs, a half-million feet of motion picture film and thousands of audio and video tapes.[16] The library also houses personal papers collections including documents from Reagan's eight years as California's governor.[16]

The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute is an independent non-profit corporation founded by Ronald Reagan that works with the National Archives and that "sustains the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in Simi Valley, CA, the Reagan Center for Public Affairs, the Presidential Learning Center, The Air Force One Pavilion, the award-winning Reagan Leadership Academy and the Reagan Institute" according to its website.[17]

When the Reagan Library opened, it was the largest of the presidential libraries, at approximately 153,000 square feet (14,200 m2).[18][19][14] It held that title until the dedication of the Clinton Presidential Center on November 18, 2004. With the opening of the 90,000-square-foot (8,400 m2) Air Force One Pavilion in October 2005, the Reagan Library reclaimed the title in terms of physical size;[20] however, the Clinton Library remains the largest presidential library in terms of materials.[21] Like all presidential libraries since that of Franklin D. Roosevelt, the Reagan Library was built entirely with private donations, at a cost of $60 million (equivalent to $120 million in 2023[22]).[14] Major donors included Walter Annenberg, Lew Wasserman, Lodwrick Cook, Joe Albritton, Rupert Murdoch, Richard Sills, and John P. McGovern.[15]

For fiscal year 2007, the Reagan Library had 305,331 visitors, making it the second-most-visited presidential library, following the Lyndon B. Johnson Library; that was down from its fiscal year 2006 number of 440,301 visitors, when it was the most visited library.[23] In 2021, it was said that the library was averaging some 375,000 annual visitors prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.[24]

Artifacts inventory

editOn November 8, 2007, Reagan Library National Archives officials reported that due to poor record-keeping, they are unable to say whether approximately 80,000 artifacts have been stolen or are lost inside the museum complex.[25] A "near-universal" security breakdown was also blamed, leaving the artifacts vulnerable to theft. Many of the nation's presidential libraries claim to be understaffed and underfunded.[26] The NARA labeled the Reagan Library as having the most serious problems with its inventory.[26] In an audit, U.S. Archivist Allen Weinstein blamed the library's poor inventory software for the mishap. Frederick J. Ryan Jr., president of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation's board of directors, said the allegations of poor management practices at the library reflect badly on the National Archives.[25] The library has undertaken an inventory project that will take years to complete.[26]

Wildfire incident

editIn the 2019 Easy Fire, the library had to be evacuated and was almost completely surrounded by the fire.[27] Earlier the same year, the brush around the buildings had been cleared by goats to create a defensible space, which helped save the facilities from burning down, according to a firefighter.[28] Olive trees used in the landscaping were damaged along with presidential banners lining the access road. A major item in the estimated half a million dollars of damage was an internet and cable box that took down the library's network.[29]

Exhibits and scenery

editThe museum features continually changing temporary exhibits and a permanent exhibit covering Reagan's life. This exhibit begins during Reagan's childhood in Dixon, Illinois, and follows his life through his film career and military service, marriage to Nancy Davis Reagan, and political career.[30] The "Citizen Governor" gallery shows footage of Reagan's 1964 "A Time for Choosing" speech and contains displays on his eight years as governor. The gallery includes a 1965 Ford Mustang used by Reagan during his first gubernatorial campaign, as well as the desk he used as governor.[31] His 1980 and 1984 presidential campaigns are also highlighted, as well as his inauguration suit and a table from the White House Situation Room is on display. News footage of the 1981 assassination attempt on his life is shown, and information about the proposed Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI, dubbed "Star Wars") is included.[32]

A full-scale replica of the Oval Office, a feature of most presidential libraries, is a prominent feature of this museum as well.[33] Among the items Reagan kept on the Resolute desk, which is replicated in the exhibit, was a 16-inch-tall (41 cm) copy of a bronze statue of "Old Bill Williams", by B. R. Pettit; Williams was a renowned mountain man of Arizona.[34] Other parts of the exhibit focus on Reagan's Rancho del Cielo, the presidential retreat Camp David, life in the White House,[35] and Nancy Reagan.[36] An example of a temporary exhibit that ran from November 10, 2007, to November 10, 2008, was titled "Nancy Reagan: A First Lady's Style" and had featured over 80 designer dresses belonging to Nancy Reagan.[37][38][39]

The hilltop grounds provide expansive views of the area, a re-creation of a portion of the White House Lawn, and a piece of the Berlin Wall.[40] An F-14 Tomcat (BuNo 162592) is also located on the grounds.[41]

In February 2016, a large equestrian statue of Reagan was installed in front of the Air Force One Pavilion.[42] Entitled "Along the Trail", it depicts Reagan riding his favorite horse, El Alamein.[7] An earlier bronze entitled "Begins the Trail", both by sculptor Donald L. Reed, stands in Dixon.[43]

Air Force One Pavilion

editA 90,000-square-foot (8,400 m2) exhibit hangar serves as the setting for the permanent display of Air Force One during Reagan's administration.[44] The aircraft, SAM 27000, was also used by six other presidents in its active service life from 1973 until 2001, including Richard Nixon during his second term, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush.[45] In 1990, it became a backup aircraft after the Boeing 747s entered into service and was retired in 2001.[45] The aircraft was flown to San Bernardino International Airport in September 2001, where it was presented to the Reagan Foundation. In what was known as Operation Homeward Bound, Boeing, the plane's manufacturer, disassembled the plane and transported it to the library in pieces.[46] After the construction of the foundation of the pavilion itself, the plane was reassembled and restored to museum quality,[46] as well as raised onto pedestals 25 feet (7.6 m) above ground.[47] The pavilion was dedicated on October 24, 2005, by Nancy Reagan, President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush.[48]

SAM 27000 is part of a comprehensive display about presidential travel that also includes a Sikorsky VH-3 Sea King during Lyndon B. Johnson's presidency, call sign Marine One,[49] and a presidential motorcade—Reagan's 1984 presidential parade limousine, a 1982 Los Angeles Police Department police car (as well as two 1980s police motorcycles), and a 1986 Secret Service vehicle used in one of President Reagan's motorcades in Los Angeles.[50] The pavilion is also home to the original O'Farrell's pub from Ballyporeen in Ireland that Ronald and Nancy Reagan visited in June 1984, now called the "Ronald Reagan Pub".[49] Also featured are exhibits on the Cold War and Reagan's extensive travels aboard Air Force One.[citation needed]

On June 9, 2008, U.S. secretary of education Margaret Spellings joined Nancy Reagan to dedicate the Reagan Library Discovery Center, located in the Air Force One Pavilion. The center is an interactive youth exhibit in which fifth through eighth grade students participate in role-playing exercises based on events of the Reagan administration.[51]

Center for Public Affairs

editOn May 23, 2007, U.S. secretary of state Condoleezza Rice and Australian foreign minister Alexander Downer held a brief private talk and a press conference.[52] On July 17, 2007, Polish president Lech Kaczyński presented Poland's highest distinction, the Order of the White Eagle, to Nancy Reagan on behalf of her husband.[53]

Funeral of Ronald Reagan

editFollowing his death, Reagan's casket was driven by hearse to the Reagan Library on June 7, 2004, from Point Mugu through a 25-mile-per-hour (40 km/h) procession down Las Posas Road to U.S. Highway 101. Many people lined the streets and freeway overpasses to pay final respects. A memorial service was held in the library lobby with Nancy Reagan, Reagan's children, close relatives, and friends. The Reverend Dr. Michael Wenning officiated at the service.

From June 7 to 9, Reagan's casket lay in repose in the library lobby, where approximately 105,000 people viewed the casket to pay their respects.[54] After the national funeral service was held in Washington, D.C., Reagan's casket was brought back to the library for a last memorial service and interment.[citation needed]

Construction plans for the library included a tomb for the eventual use of Reagan and his wife. Following a sunset service on the library grounds the previous evening, early on the morning of June 12, Reagan was laid to rest in the underground vault.[55]

Nancy Reagan died on March 6, 2016. After her funeral, she was buried next to her husband at the library on March 11.[56]

Republican primary debates

editOn May 3, 2007, the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Nancy Reagan hosted the first 2008 Republican primary debate in the library's Air Force One Pavilion. During the debate, candidates made at least 20 references to Ronald Reagan and his presidency.[57] On January 30, 2008, the library was the scene of the final debate, once again hosted by the Reagan Foundation and Mrs. Reagan.[58][better source needed]

The library announced that it would once again host the first Republican primary debate among 2012 Republican candidates, initially scheduled for May 2, 2011,[59] but later postponed it until after other debates.[60] The debate was co-hosted by NBC News and Politico. The debate took place on September 7, 2011.[61]

In September 2015, the library hosted the second 2016 Republican presidential debate, which was run by CNN.[62] The second debate of the 2024 Republican presidential primaries was held on September 27, 2023 at the library.[63]

Centennial and library renovation

editThe Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and General Electric (GE) announced a partnership beginning March 17, 2010, to support the two-year-long celebration of Reagan's 100th birthday on February 6, 2011. GE, for whom Reagan hosted General Electric Theater and served as a goodwill ambassador from 1954 to 1962, prior to being elected governor of California, served as the Presenting Sponsor of the historic Reagan Centennial Celebration.[64]

The Reagan Centennial was also being led by the National Youth Leadership Committee. Notable members of the Committee include chairpersons Nick Jonas, Jordin Sparks and Austin Dillon, as well as famous non-chairpersons, including actress Anna Maria Perez de Tagle, Olympic bronze medalist Bryon Wilson, Olympian and X-Games medalist Hannah Teter, and recording artist Jordan Pruitt. Several other Olympians and athletes are also members of the committee.[65]

2023 Tsai–McCarthy meeting

editOn April 5, 2023, Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen and U.S. House speaker Kevin McCarthy met at the library. The meeting was significant as it marked the first time a Taiwanese president had met with a U.S. House Speaker on American soil. It was also significant as it was the second time in less than a year that a Taiwanese president had met with a U.S. House speaker since Tsai met with then-speaker Nancy Pelosi in Taipei in August 2022.[66] In response to the meeting, the Foreign Ministry of China imposed sanctions on the Reagan Library.[67]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Mitchell, Gordon R.; Kirk, Jennifer (Spring 2008). "Between Education and Propaganda: Public Controversy Over Presidential Library Design". Argumentation and Advocacy. 44 (4): 213–230. doi:10.1080/00028533.2008.11821691. S2CID 141364164.

- ^ a b "Liberal-conservative debate at Stanford's Hoover Institute". Christian Science Monitor. June 28, 1983.

- ^ "Reagan Library at Stanford OK'd". Milwaukee Journal. February 15, 1984. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2012 – via Google News.

- ^ Turner, Wallace (February 15, 1984). "Stanford to be the Site of the Reagan Library". New York Times.

- ^ Lindsey, Robert (April 24, 1987). "Plan for Reagan Library at Stanford Is Dropped". The New York Times. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Enriquez, Sam (November 14, 1987). "Ventura County Site Picked for Reagan Library". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Bartholomew, Dana (February 4, 2016). "Reagan's 105th birthday to be celebrated with new statue, coins". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ a b Sandler, Norman D. (January 28, 1987). "The design of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, unveiled..." United Press International. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ "Reagan Plan for a Library is Displayed". The New York Times. January 31, 1987. Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved June 9, 2023.

- ^ "Women's Lyceum focuses on innovation". BizJournals.com. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Miller, Linda (April 26, 1992). "Reagan Library Designer Strives for Warmth in Exhibit". Daily Oklahoman. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Riechers, Angela. "2014 AIGA Medalist Michael Donovan and Nancye Green". AIGA. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ "Museum". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ a b c Mydans, Seth (November 1, 1991). "Elite Group to Dedicate Reagan Library". The New York Times. Retrieved November 19, 2007.

- ^ a b Giller, Melissa (2003). "Reagan Presidential Library". In Drake, Miriam A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science. Vol. 4. CRC Press. p. 2456. ISBN 0-8247-2080-6.

- ^ a b c "Archives: The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ "About Us". www.reaganfoundation.org. Retrieved October 19, 2023.

- ^ Hufbauer, Benjamin (December 1, 2008). "The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum". Journal of American History. 95 (3): 786–92. doi:10.2307/27694381. JSTOR 27694381.

- ^ Lopez, Natalina (July 1, 2016). "How Will the Obama Presidential Library Stack Up?". Town and Country Magazine. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

Perched on a hillside in Simi Valley, California, the Reagan Library wins the prize for being the largest of the presidential libraries.

- ^ "Winds Tear Air Force One Pavilion Roof at Reagan Library". Ventura County Star. November 3, 2007. Archived from the original on January 3, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ "Library Museum and Information". Clinton Presidential Library and Museum. Archived from the original on November 17, 2007. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Presidential Libraries on C-SPAN: Exclusive Series Interviews and Additional Footage (Documentary). C-SPAN. November 30, 2007. Event occurs at 1:32:03, 1:32:55. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Harris, Mike. "'Something more than the typical presidential library:' Reagan celebrates 30 years". Ventura County Star. Retrieved May 7, 2024.

- ^ a b Chawkins, Steve & Salliant, Catherine (November 9, 2007). "The Talk of the Reagan Library". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ a b c Alonso-Zaldivar, Ricardo & Salliant, Catherine (November 10, 2007). "Reagan Library Has Lost Thousands of Artifacts". Tampa Tribune. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ Matt Stieb (October 30, 2019). "Reagan Library Evacuated As Easy Fire Encroaches". Intelligencer. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ May, Patrick (October 31, 2019). "A shout-out to those grass-gnawing goat fire brigades". The Mercury News. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- ^ Shalby, Colleen (November 18, 2019). "Easy fire cost Reagan Library $500,000, including destroyed banners and olive trees". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ "Early Years Gallery". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Citizen Governor Gallery". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "New Beginnings Gallery". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "The Oval Office". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Old Bill Williams sculpture". Arizona Highways: 38. May 1985. WPS33940.

- ^ "The President's Residences". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "First Lady Nancy Reagan". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on February 8, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Corcoran, Monica (November 11, 2007). "The Nancy Years". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Bakalis, Anna (November 9, 2007). "Style Exhibit Chronicles Nancy Reagan's Life". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on March 5, 2009. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- ^ "Calendar of Events". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on August 22, 2007. Retrieved December 2, 2007.

- ^ Mason, Dave (November 7, 2023). "Artists restore Berlin Wall segment at Reagan library in Simi Valley". Ventura County Star. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ LACEY, MARC (January 18, 1991). "Stemming the Tide : Endangered Plant Has Knack of Blocking Construction". LA Times. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ^ Joseph, Dana (February 2016). "Ronald Reagan Rides Again". Cowboys & Indians. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ Griggs, Gregory W. (November 2, 2006). "Reagan rides again -- this time in bronze". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ "Air Force One Pavilion". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Facts and Stats". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on November 7, 2007. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Reagan Air Force One Moves to Presidential Library" (Press release). Boeing. June 20, 2003. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- ^ "The Journey of Air Force One". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 22, 2007. Retrieved December 3, 2007.

- ^ Bush, George W. (October 21, 2005). President Participates in Opening Ceremony for Air Force One Pavilion (Speech). Simi Valley, California. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Permanent Galleries". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on November 21, 2007. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ "Permanent Galleries: Presidential Motorcade". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Archived from the original on August 14, 2007. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ Carlson, Cheri (June 9, 2008). "'Unmatched Creativity' at Reagan Library's Discovery Center". Ventura County Star. Archived from the original on June 10, 2008. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ^ Serjeant, Jill (May 23, 2007). "Rice, Australian Minister Evoke Reagan in Iraq Talk". Reuters. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- ^ Nasby, Robin (July 27, 2007). "Rare Visit from Polish President Draws Far-Off Visitors to Simi". Simi Valley Acorn. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Transcripts: American Morning". CNN. June 10, 2004. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Welzenbach, Dennis (June 7, 2004). "Burial of a President: A Behind the Scenes Diary". Suhor Industries. Archived from the original on September 1, 2012. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ Sewell, Abby (March 6, 2016). "Nancy Reagan: Visitors pay their respects at the presidential library in Simi Valley". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Nagourney, Adam & Santora, Marc (May 4, 2007). "Republicans Differ on Defining Party's Future". The New York Times. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "Romney Blasts McCain over Iraq War Charge". Fox News. Associated Press. January 30, 2008. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Camia, Catalina (November 11, 2010). "Nancy Reagan to Host Debate for 2012 GOP Hopefuls". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012.

- ^ Hendin, Robert (March 30, 2011). "First Republican presidential debate postponed". CBS News.

- ^ "The Republican Debate at the Reagan Library". New York Times. September 7, 2011.

- ^ Hohmann, James & Isenstadt, Alex (January 16, 2015). "2016 Presidential Debate Schedule: Republican Party rolls out dates". Politico.

- ^ Isenstadt, Alex (August 1, 2023). "Revealed: The criteria and date for the second Republican primary debate". Politico. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ "Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation Announces GE as Presenting Sponsor of the Ronald Reagan Centennial Celebration" (Press release). General Electric. March 17, 2010. Archived from the original on September 26, 2011.

- ^ Jackson, David (August 3, 2010). "Ronald Reagan Centennial Includes Youth Leadership". USA Today. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- ^ "McCarthy welcomes Taiwan President to bipartisan meeting, optimistic US and Taiwan can promote 'democracy, peace and stability'". CNN. April 5, 2023.

- ^ "China sanctions Reagan library, others over Tsai's US trip". Associated Press. April 7, 2023. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

External links

edit- Official website

- The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library

- The Ronald Reagan Centennial Celebration

- Video of the dedication of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, 1991

- Video of the Gravesite of Ronald Reagan at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

- Video of the Replica of the Oval Office at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

- U.S. National Archives and Records Administration