Rarh region (Bengali pronunciation: [raːɽʱ]) is a toponym for an area in the Indian subcontinent that lies between the Chota Nagpur Plateau on the West and the Ganges Delta on the East. Although the boundaries of the region have been defined differently according to various sources throughout history, it is mainly coextensive with the state of West Bengal, also comprising parts of the state of Jharkhand in India.

Rarh

Rāḍha | |

|---|---|

Map showing the area of Rarh | |

| Coordinates: 23°15′N 87°04′E / 23.25°N 87.07°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | East India |

| Government | |

| • Body | Government of West Bengal, Government of Jharkhand |

| Language | |

| • Dialect | Rarhi dialect |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Bengali |

| • Other languages | Santhali, Kudmali |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| Vehicle registration | WB-11,WB-12,WB-14,WB-15,WB-16,WB-18,WB-29,

WB-30,WB-31,WB-32,WB-33,WB-34,WB-36,WB-37, WB-38,WB-39,WB-40,WB-41,WB-42,WB-44,WB-53, WB-54,WB-55,WB-56,WB-57,WB-WB-58,WB-67, WB-68[citation needed] |

| Major Cities | Asansol, Durgapur, Bardhaman, Bankura, Howrah, Nabadwip |

| Civic agency | Government of West Bengal |

The Rarh region historically has been known by many different names and has hosted numerous settlements throughout history. One theory identifies it with the powerful Gangaridai nation mentioned in the ancient Greco-Roman accounts. The Naihati copper plate inscription of King Ballal Sen names it as the ancestral settlement of the Sena dynasty.

Etymology and names

editRāḍha (Sanskrit) and Lāḍ[h]a (Prakrit) are the ancient names of the Rarh region.[1] Other variations of the name that appear in the ancient Jain literature include Rarha, Lara, and Rara.[2] The Sri Lankan Buddhist chronicles such as Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa state that the legendary Prince Vijaya came from a region called Lāla, which is identified with Rāḍha by several scholars.[3]

In a 1972 thesis, the researcher Amalendu Mitra traced the origin of the word Rarh to "lāṛ", the Santali word for snake. This theory was also endorsed by his mentor Panchanan Mandal. However, German Indologist Rahul Peter Das notes that this is highly unlikely: the Santali word "lāṛ" actually means string or fibre, and is sometimes used for "snake" or "twig".[4] Das further points out that the word "lāṛ" may itself be an Indo-Aryan loanword in Santali.[4]

"Gangaridai", the name of an ancient Bengali people in Greek literature, is sometimes believed to be a Greek corruption of "Ganga-Rāḍha". However, according to D. C. Sircar, the word is simply the plural form of "Gangarid" (which is derived from the base "Ganga"), and means "Ganga (Ganges) people".[5]

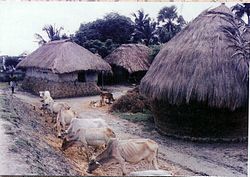

Many aspect of Rarh are found in these books entitle as 'Subarnarekha hoite Mayurakshi[6] and Rarher Mantrayan[7] authored by Maniklal Sinha. Rarher Mantrayan[7][8] contains the ancient manuscripts of tantra and mantra, raveling various villages, and mixing with 'Mantrayanis' in Rarh. Whereas, Subarnarekha hoite Mayurakshi[6] is based on the tribal lifestyle, introducing various tribes, their festivals, clothing's, culture of Hazaribag, Singbhum, Manbhum, Dhalbhum Shikarbhum, Santal Pargana and Bankura that are situated in the basin of the river Subarnarekha. The author also discussed about the landscape of those laces and the influence of Buddhism on the tribal religion.

Geography

editThe Rarh region lies between the Chota Nagpur Plateau on the west[9] and the chief flow of the Ganges river (which has been continuously changing) in the east.[1] The Rarh plains comprise the lower Gangetic plains to the south of the Ganges, and to the west of its Bhagirathi-Hooghly distributary.[10] These plains are formed of old alluvial deposits. The elevation ranges between 75 and 150 m.[11]

Low-level Pleistocene-era lateritic badlands (locally called khoai) are common in the region.[12] Several of these small hillocks were formed as a result of subaerial erosions and other tectonic movements. The highest of these are Biharinath (440 m) and Susunia (440 m). Biharinath contains sedimentary rocks of Gondwana system. Susunia contains gneissic and schistose rocks of Archean age, and also felspathic quartzite at its top.[11]

The major rivers in the region include Damodar, Ajay, Mayurakshi, Dwarakeswar, Shilabati (Shilai), and Kangsabati River (Kasai).[13][14] All these rivers originate from Chota Nagpur Plateau and flows towards east or south-east finally to meet the River Hooghly. The river Subarnarekha flows through some parts of the region in the Midnapur district.[15] In the past, the floods of Damodar, called the "Sorrow of Bengal", often resulted in heavy losses to life and property. After the formation of the Damodar Valley Corporation in 1948, the flood hazard in the Rarh plain has been reduced through the construction of heavy embankments and other sophisticated engineering structures.[citation needed]

West Rarh's Bagri river is a fertile, low-lying alluvial tract. Rice, jute, legumes, oilseeds, wheat, barley, and mangoes are the chief crops in the east; extensive mulberry cultivation is carried out in the west.[9]

Rarh has several moist deciduous forests of Shorea robusta (sal), Magnolia champaca (champak) and Acacia.[13]

Extent

editAccording to Rupendra Kr Chattopadhyay, the historical Rarh region cover parts of the following districts, divided into northern and southern Rarh by the Damodar river:[2]

- Northern Rarh (Uttāra-Rādha): Certain parts of Birbhum, Burdwan, Murshidabad, and Nadia

- Southern Rarh (Dakshin-Rādha): Certain parts of Burdwan, Bankura, Hooghly and Howrah

P. R. Sarkar defines the Rarh region as follows:[16]

- Eastern Ráŕh consists of roughly:

- Western Murshidabad

- Nabadwip of Nadia district

- The northern part of Birbhum

- Eastern Burdwan

- The whole of Hooghly

- The whole of Howrah district

- The Indas Police Station of Bankura district

- Western Rarh consists of the following districts:

- Most parts of Birbhum

- Western Burdwan

- Bankura district except for Indas

- Purulia

- Northern part of Paschim Medinipur

- Certain part of Jhargram

History

editThe earliest reference to Rāḍha janapada (as "Ladha") is found in the Jain text Acharangasutra. The text states that the 6th century BCE spiritual leader Mahavira traveled in Vajjabhumi and Subbhabhumi, which were located in the Ladha country. It mentions that the region was "pathless and lawless" during this time, and the local people treated Mahavira harshly.[2]

One theory identifies Rarh with the powerful Gangaridai people described in the ancient Greek literature.[17] The Greek writer Diodorus Siculus mentions that the Ganges river formed the eastern boundary of the Gangaridai. Based on his statement and the identification of Ganges with Bhāgirathi-Hooghly (a western distributary of Ganges), Gangaridai can be identified with the Rarh region. However, other writers such as Plutarch, Curtius and Solinus, suggest that Gangaridai was located on the eastern banks of the Gangaridai river.[17] Moreover, Pliny states that the Gangaridai occupied the entire region about the mouths of the Ganges.[18] This suggests that the Gangaridai territory included the larger coastal region of present-day West Bangal and Bangladesh, from the Bhāgirathi-Hooghly River in the west to the Padma River in the east.[18]

The legendary Sri Lankan chronicles Mahavamsa and Dipavamsa mention that Prince Vijaya, the founder of their nation, came from Simhapura city in the "Lala" country. This Lala is identified with Rāḍha.[2]

The earliest epigraphic evidence to Rāḍha probably appears in an inscription from Mathura. This inscription states that a Jain monk from the "Rara" country erected a Jain image. A Khajuraho inscription mentions that the Chandela ruler imprisoned the wives of the rulers of various kingdoms, which included Rāḍha.[2]

The 12th century Naihati copper-plate inscription of the Sena ruler Vallalasena mentions Rāḍha as the ancestral place of his dynasty.[2]

Historical extent

editVarious ancient and medieval region offer clues about the location and historical extent of the Rarh region. The Bhuvaneshvara inscription of Bhatta Bhavadeva, a 12th-century minister, describes Rāḍha as "a waterless, dry and woody region". This description suits the western part of Bengal. The 16th century Digvijayaprakasha suggests that Rāḍha was located to the north of the Damodar River, and to the south of the Gauda region.[2] The 13th century chronicle Tabaqat-i Nasiri by Minhaj-i-Siraj defines Rāḍh (Rāḍha) as the section lying to the west of the Hoogly-Bhagirathi River.[19]

According to Rupendra K Chattopadhyaya of Banglapedia, Rāḍha "probably included a large part of the modern Indian state of West Bengal".[2] According to historian André Wink, the Rāḍha division of the Pala-Sena era corresponds roughly to the modern Bardhaman district.[20]

Divisions

editThe 9th–10th century literature and inscriptions and literature mention two divisions of Rāḍha: northern (Uttara) and southern (Dakṣiṇa). Rupendra K Chattopadhyaya (in Banglapedia) believes that these roughly correspond to the Subbhabhumi and Vajjabhumi mentioned in the ancient Jain literature.[2] The 17th century scholar Nilakanatha mentions Suhma as a synonym of Rāḍha. However, as Subbhabhumi is a corruption of Suhma, it appears that Suhma referred to only a part of the ancient Rāḍha region.[21]

Uttara Rāḍha

editA 6th century CE inscription of the Chola king Devendravarman is the earliest inscription to mention Uttara Rāḍha. The 12th century Belava copper inscription of Bhojavarman states that Bhatta Bhavadeva was born in the Siddhala village (modern Siddhalagram) of Uttara Rāḍha. The 12th century Naihati inscription of Vallalasena also mentions a village named Vallahittaha in the Uttara-Rāḍha mandala (administrative unit). It suggests that Uttara Rāḍha was a part of the Vardhaman bhukti (province). However, the inscription of Vallalasena's successor Lakshmanasena states that this region was a part of the Kankagram bhukti.[2]

Based on these records, Rupendra K Chattopadhyaya believes that the Uttara Rāḍha included the western parts of the modern Murshidabad district, the entire Birbhum district, some parts of the Santal Parganas district, and the northern part of the Katwa subdivision of the Bardhaman district.[2]

The archaeological sites located in the historical Uttara Rāḍha region include Rajbadidanga, Gitagram, Paikor, Batikar, Bahiri, Kagas, Kotasur, and Vallala-rajar-dhibi (Ballal Dhipi).[2]

Dakṣina Rāḍha

editDakṣina Rāḍha appears as a distinct unit in several inscriptions, including the 10th century Gaonri inscription of Vakpati Munja, the 10th century Nyayakandali of Sridhara-acharya, the 11th century Prabodha-Chandrodaya by Krishna Mishra, the 13th century Amareshvara temple inscription of Mandhata, and the 16th century Chandimangal by Mukundarama. The 11th century CE Tirumalai inscription of Rajendra Chola I also mentions "Ladam" (Uttara Rāḍha) and "Takkana-Ladam" (Dakṣina Rāḍha) as two distinct units.[2]

Rupendra K Chattopadhyaya theorizes that the Dakṣiṇa Rāḍha covered a large of part of West Bengal lying between the Ajay and Damodar rivers. This includes large parts of the later Bardhaman, Howrah, and Hughli, and Burdwan districts. The southern boundary of Dakṣiṇa Rāḍha may have extended to the Rupnarayan River, and its western boundary extended beyond the Damodar river into the present-day Arambag subdivision.[2]

The archaeological sites that formed part of Dakṣina Rāḍha include: Mahanad, Betur, Saptagram, Garh Mandaran, Bharatpur, Mangalkot, and possibly Dihar and Puskarana.[2]

Notable people of Rarh

editRarh presented human society the first philosopher Maharishi Kapila who was born near Jahlda. Maharishi Patanjali who systematised yoga was born in Patun village in Burdwan. Kashiram Das from Siddhi village in Burdwan made the Mahabharata in lucid language accessible to the people and Krittibas Ojha did the same with the Ramayana. 15th century Indian saint and social reformer Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, who is the chief proponent of vedantic philosophy of Achintya Bheda Abheda and Gaudiya Vaishnavism, was born in Nabadwip village of Nadia district. Others were born in Rarh or were by lineage from Rarh such as: Lochandas Thakur, Vrindavandas Thakur, Govindadas Thakur, Dvaja Chandidas, Dina Chandidas, Boru Chandidas, Ghanaram Chakravorty, Kavikankan Mukundaram Chakravorty, Bharatchandra Ray, Premendra Mitra, Sangeetacharya Kshetramohan Goswami, Sharatchandra, Tarashankar Bandopadhyay, the poet Jaydev, Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore, Sangeetacharya Rajendranath Karmakar, Anil Kumar Gain, Michael Madhusudan Dutta, Kazi Nazrul Islam, Satyen Dutta, Rajshekhar Basu (Parashuram), legendary mathematician Shubhankar Das, Kashana, Jayanta Panigrahi, Ishwarchandra Vidyasagar, Satyendranath Bose, Rashbehari Bose, Prafulla Chandra Roy, Subhas Chandra Bose, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Swami Vivekananda, Shri Aurobindo, Raja Rammohan Roy, Kaliprasanna Singha, Ramprasad Sen, Keshab Chandra Sen, Akshay Kumar Datta, Devendranath Tagore, Dwarakanath Tagore, Thakur Shri Nityananda, Abanindranath Tagore, Gaganendranath Tagore, Batukeswar Dutt, Thakur Krshnadas Kaviraj, Yamini Ray, Maniklal Sinha,[6][7][8] Kaberi Gain, Ramkinkar Baij, Kalidasa, Kshudiram Bose, and Satyajeet Ray.[16]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Rahul Peter Das 1983, p. 664.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Rupendra Radha 2012.

- ^ Shyuam Chand Mukherji 1966, pp. 35–36.

- ^ a b Rahul Peter Das 1983, p. 669.

- ^ Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 171, 215.

- ^ a b c Singha, Maniklal (1988). Subarnarekha hoite Mayurakshi (in Bengali). Bishnupur: Bangiya Sahtya Parisad: Bishnupur. Bankura.

- ^ a b c Singha, Maniklal (1979). Rardher Mantrajan (in Bengali). Bishnupur: Sri Chittaranjan Dasgupta.

- ^ a b Mukharji, Projit Bihari (16 December 2019). 25. Rediscovering Living Buddhism in Modern Bengal: Maniklal Singha's The Mantrayāna of Rārh (1979). Columbia University Press. pp. 231–234. doi:10.7312/salg18936-028. ISBN 978-0-231-54830-4. S2CID 213713375.

- ^ a b "Rarh". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ^ Students Britannica 2000, p. 239.

- ^ a b Anita Roy Mukherjee 1995, p. 22.

- ^ Balai Chandra Das 2016, p. 20.

- ^ a b Students Britannica 2000, p. 240.

- ^ Praṇaba Chattopadhyaya 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Anita Roy Mukherjee 1995, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b Sarkar, Shrii Prabhat Ranjan (2004). Ráŕh – The Cradle of Civilization. Ananda Marga Publications. OCLC 277280070.

- ^ a b Nitish K. Sengupta 2011, p. 28.

- ^ a b Dineschandra Sircar 1971, p. 172.

- ^ Mohammad Yusuf Siddiq 2015, p. 27.

- ^ André Wink 2002, p. 257.

- ^ Rupendra Suhma 2012.

Bibliography

edit- André Wink (2002). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL. ISBN 0-391-04173-8.

- Anita Roy Mukherjee (1995). Forest Resources Conservation and Regeneration: A Study of West Bengal Plateau. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-7022-562-1.

- Balai Chandra Das; Sandipan Ghosh; Aznarul Islam; MD. Ismail (2016). Neo-Thinking on Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin Geomorphology. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-26443-1.

- Dineschandra Sircar (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0690-0.

- Gouripada Chatterjee (1987). History of Bagree-Rajya (Garhbeta). Mittal. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-7099-014-7.

- Mohammad Yusuf Siddiq (2015). Epigraphy and Islamic Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-58746-0.

- Nitish K. Sengupta (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

- Praṇaba Chattopadhyaya (2004). Archaeometallurgy in India: Studies on technoculture in early copper and iron ages in Bihar, Jharkhand, and West Bengal. Kashi Prasad Jayaswal Research Institute.

- Rupendra K Chattopadhyaya (2012). Sirajul Islam; Ahmed A. Jamal (eds.). Banglapedia: Radha (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-32-0584-1.

- Rupendra K Chattopadhyaya (2012). Sirajul Islam; Ahmed A. Jamal (eds.). Banglapedia: Suhma (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 978-984-32-0584-1.

- Rahul Peter Das (1983). "Some Remarks on the Bengali Deity Dharma: Its Cult and Study". Anthropos. 78 (5/). Anthropos Institut: 661–700. JSTOR 40460739.

- Students' Britannica India. Encyclopaedia Britannica / Popular Prakashan. 2000. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.

- Shyuam Chand Mukherji (1966). A Study of Vaiṣṇavism in Ancient and Medieval Bengal. Punthi Pustak. OCLC 220444592.