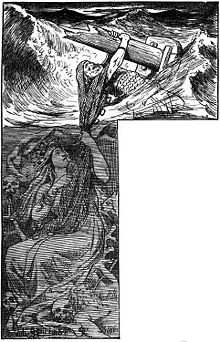

In Norse mythology, Rán (Old Norse: [ˈrɒːn]) is a goddess and a personification of the sea. Rán and her husband Ægir, a jötunn who also personifies the sea, have nine daughters, who personify waves. The goddess is frequently associated with a net, which she uses to capture sea-goers. According to the prose introduction to a poem in the Poetic Edda and in Völsunga saga, Rán once loaned her net to the god Loki.

Rán is attested in the Poetic Edda, compiled during the 13th century from earlier traditional sources; the Prose Edda, written during the 13th century by Snorri Sturluson; in both Völsunga saga and Friðþjófs saga hins frœkna; and in the poetry of skalds, such as Sonatorrek, a 10th-century poem by Icelandic skald Egill Skallagrímsson.

Etymology

editThe Old Norse common noun rán means 'plundering' or 'theft, robbery'.[1] In turn, scholars view the theonym Rán as meaning, for example, 'theft, robbery'.[2] On the etymology of the theonym, scholar Rudolf Simek says, "although the meaning of the name has not been fully clarified, Rán was probably understood as being 'robber' ... and has nothing to do with [Old Norse] ráða 'rule'.[2]

Because Rán is a personification of the sea, skalds employ her name in a variety of kennings to refer to the sea. Examples include Ránar-land ('Ran's land'), -salr ('Rán's hall'), and -vegr ('Rán's way'), and rán-beðr ('the bed of Rán') and meaning 'the bed of the sea'.[3]

Attestations

editSonatorrek

editRán and Ægir receive mention in the poem Sonatorrek attributed to 10th century Icelandic skald Egill Skallagrímsson. In the poem, Egill laments the death of his son Böðvar, who drowned at sea during a storm:

- Old Norse:

- Mjök hefr Rán rykst um mik;

- emk ofsnauðr at ástvinum.

- Sleit marr bönd mínnar áttar,

- snaran þátt af sjalfum mér.[4]

- Nora K. Chadwick translation:

- Greatly has Rán afflicted me.

- I have been despoiled of a great friend.

- Empty and unoccupied I see the place

- which the sea has torn my son.[5]

In one difficult stanza later in the poem, the skald expresses the pain of losing his son by invoking the image of slaying the personified sea, personified as Ægir (Old Norse ǫlsmið[r] 'ale-smith') and Rán (Ægis man 'Ægir's wife'):

|

|

Poetic Edda

editRán receives three mentions in the Poetic Edda; twice in poetry and once in prose. The first mention occurs in a stanza in Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, when the valkyrie Sigrún assists the ship of the hero Helgi Hundingsbane as it encounters ferocious waters:

Henry Adams Bellows translation

- But from above did Sigrun brave

- Aid the men and all their faring;

- Mightily came from the claws of Ron

- The leader's sea-beast off Gnipalund.[8]

Carolyne Larrington translation

- And Sigrun above, brave in battle,

- protected them and their vessel;

- the king's sea-beasts twisted powerfully,

- out of Ran's hand toward Gnipalund.[9]

In the notes for her translation, Larrington says that Rán "seeks to catch and drown men in her net" and that "to give someone to the sea-goddess is to drown them."[10]

The second instance occurs in a stanza found in Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar. In this stanza, the hero Atli references Rán while flyting with Hrímgerðr, a female jötunn:

Henry Adams Bellows translation:

- "Witch, in front of the ship thou wast,

- And lay before the fjord;

- To Ron wouldst have given the ruler's men,

- If a spear had not stuck in thy flesh."[11]

Carolyne Larrington translation:

- 'Ogress, you stood before the prince's ships

- and blocked the fjord mouth;

- the king's men you were going to give to Ran,

- if a spear hadn't lodged in your flesh.'[12]

Finally, in the prose introduction to Reginsmál, Loki visits Rán (here rendered as Ron) to borrow her net:

- [Odin and Hœnir] sent Loki to get the gold; he went to Ron and got her net, and went then to Andvari's fall and cast the net in front of the pike, and the pike leaped into the net.[13]

Translator Henry Adams Bellows notes how this version of the narrative differs from how it appears in other sources, where Loki catches the pike with his own hands.[13]

Prose Edda

editThe Prose Edda sections Skáldskaparmál and Háttatal contain several references to Rán. Section 25 of Skáldskaparmál ("How shall sea be referred to?") manners in which poets may refer to the sea, including "husband of Ran" and "land of Ran and of Ægir's daughters", but also "father of Ægir's daughters".[14]

In the same section, the author cites a fragment of a work by the 11th century Icelandic skald Hofgarða-Refr Gestsson, where Rán is referred to as 'Gymir's ... völva':

|

Standardized Old Norse

|

Anthony Faulkes translation

|

The section's author comments that the stanza "[implies] that they are all the same, Ægir and Hler and Gymir.[17] The author follows with a quote from another stanza by the skald that references Rán:

Chapter 33 of Skáldskaparmál discusses why skalds may refer to gold as "Ægir's fire". The section traces the kenning to a narrative surrounding Ægir, in which the jötunn employs "glowing gold" in the center of his hall to light it "like fire" (which the narrator compares to flaming swords in Valhalla). The section explains that "Ran is the name of Ægir's wife, and the names of their nine daughters are as was written above ... Then the Æsir discovered that Ran had a net in which she caught everyone that went to sea ... so this is the story of the origin of gold being called fire or light or brightness of Ægir, Ran or Ægir's daughters, and from such kennings the practice has now developed of calling gold fire of the sea and of all terms for it, since Ægir and Ran's names are also terms for the sea, and hence gold is now called fire of lakes or rivers and of all river-names."[18]

In the Nafnaþulur section of Skáldskaparmál, Rán appears in a list of goddesses (Old Norse ásynjur).[19]

Völsunga saga and Friðþjófs saga hins frœkna

editRán receives a single mention in Völsunga saga. Like in the prose introduction to the eddic poem Reginsmál (discussed above), "they sent Loki to obtain the gold. He went to Ran and got her net."[20]

In the legendary saga Friðþjófs saga hins frœkna, Friðþjófr and his men find themselves in a violent storm, and the protagonist mourns that he will soon rest in Rán's bed:

|

Old Norse

|

Eiríkr Magnússon and William Morris translation (1875):

|

The protagonist then decides that as they are to "go to Rán" (at til Ránar skal fara) they would better do so in style with gold on each man. He divides the gold and talks of her again:

|

|

Scholarly reception and interpretation

editAccording to Rudolf Simek, "... Rán is the ruler of the realm of the dead at the bottom of the sea to which people who have drowned go." Simek says that "while Ægir personifies the sea as a friendly power, Rán embodies the sinister side of the sea, at least in the eyes of the late Viking Age Icelandic seafarers."[2]

See also

edit- Sessrúmnir, the hall of the goddess Freyja, which may have been conceived of as a ship

Notes

edit- ^ Faulkes (1998: 250) and discussion in Simek (2007 [1993]: 260).

- ^ a b c Simek (2007 [1993]: 260).

- ^ Gudbrund Vigfusson (1874: 487–488).

- ^ Kershaw (1922:134).

- ^ Kershaw (1922:135). Formatted for display.

- ^ Einarsson 2003, p. 149.

- ^ Einarsson (2003:149). Formatted for display.

- ^ Bellows (1936: 299–300). Bellows renders Old Norse Rán as Ron throughout his translation.

- ^ Larrington (1999 [1996]: 118).

- ^ Davidson (1999 [1996]: 279, 280).

- ^ Bellows (1936: 281).

- ^ Davidson (1999 [1996]: 127).

- ^ a b Bellows (1936: 358–359).

- ^ Faulkes (1995 [1989]: 91).

- ^ Faulkes (1998: 37).

- ^ Faulkes (1995 [1989]: 91). Formatted for display. This stanza appears quoted a second time later in Skáldskaparmál, for which see Faulkes (1995 [1989]: 140).

- ^ a b Faulkes (1998: 92).

- ^ Faulkes (1998:95). The chapter continues with discussion regarding the development of these kennings and the concept of allegory.

- ^ Faulkes (1998: 157).

- ^ Byock (1990: 58).

- ^ a b Friðþjófs saga ins frækna at Norrøne Tekster og Kvad, Norway.

- ^ Eiríkr Magnússon and Morris (1875: 84).

- ^ Eiríkr Magnússon and Morris (1875: 86).

References

edit- Byock, Jesse. 1990. Trans. The Saga of the Volsungs. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27299-6

- Einarsson, Bjarni, ed. (2003). Egils saga (PDF). London: Viking Society for Northern Research. ISBN 9780903521543.

- Kershaw, Nora. 1922. Trans. Anglo-Saxon and Old Norse Poems. Cambridge at the University Press.

- Eiríkr Magnússon and Morris, William. Trans. 1875. Three Northern Love Stories and Other Tales. Ellis & White.

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.). 1995 [1989]. Trans. Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Faulkes, Anthony. (Editor). 1998. Trans. Edda: Skáldskaparmál. I. Viking Society for Northern Research.

- Gudbrandur Vigfusson. 1874. Trans. An Icelandic-English Dictionary: Based on the Ms. Collections of the Late Richard Cleasby. Clarendon Press.

- Bellows, Henry Adams. 1936. Trans. The Poetic Edda. Princeton University Press. New York: The American-Scandinavian Foundation.

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.). 1999 [1996]. Trans. The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Simek, Rudolf. 2007 [1993]. Translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1