Rage Against the Machine (often abbreviated as RATM or shortened to Rage) was an American rock band formed in Los Angeles, California in 1991. The band consisted of vocalist Zack de la Rocha, bassist and backing vocalist Tim Commerford, guitarist Tom Morello, and drummer Brad Wilk. They melded heavy metal and rap music, punk rock and funk with anti-authoritarian and revolutionary lyrics. As of 2010, they had sold over 16 million records worldwide.[1] They were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2023.[2][3]

Rage Against the Machine | |

|---|---|

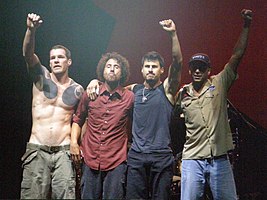

Rage Against the Machine in 2007. From left: Tim Commerford, Zack de la Rocha, Brad Wilk, Tom Morello | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Discography | Rage Against the Machine discography |

| Years active |

|

| Labels | |

| Spinoffs | |

| Past members | |

| Website | ratm |

Rage Against the Machine released their self-titled debut album in 1992 to acclaim; in 2003, Rolling Stone ranked it number 368 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time. They achieved commercial success following their performances at the 1993 Lollapalooza festival.[4] Their next albums, Evil Empire (1996) and The Battle of Los Angeles (1999), topped the Billboard 200 chart.[5][6] During their initial nine-year run, Rage Against the Machine became a popular and influential band,[7] and influenced the nu metal genre which came to prominence during the late 1990s and early 2000s. They were also ranked No. 33 on VH1's 100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock.[8]

In 2000, Rage Against the Machine released the cover album Renegades and disbanded after growing creative differences led to De la Rocha's departure. After pursuing other projects for several years, they reunited to perform at Coachella in 2007. Over the next four years, the band played live venues and festivals around the world before going on hiatus in 2011. In 2019, Rage Against the Machine announced a world tour that was delayed to 2022 due to the COVID-19 pandemic but was cut short after de la Rocha suffered a leg injury. Wilk confirmed in 2024 that the band had disbanded for the third time.[9]

History

edit1991–1992: Early years

editIn 1991, following the break-up of guitarist Tom Morello's former band Lock Up, former Lock Up drummer Jon Knox encouraged Tim Commerford and Zack de la Rocha to jam with Morello as he was looking to start a new group.[10] Morello soon contacted Brad Wilk, who had unsuccessfully auditioned for both Lock Up[10] and the band that would later become Pearl Jam.[11] This lineup named themselves Rage Against the Machine, after a song De la Rocha had written for his former underground hardcore punk band Inside Out (also to be the title of the unrecorded Inside Out full-length album).[10] Record label owner and zine publisher Kent McClard, with whom Inside Out was associated, coined the phrase "rage against the machine" in a 1989 article in his zine No Answers.[12]

The blueprint for the group's major-label debut album and demo tape Rage Against the Machine was laid on a twelve-song self-released cassette, the cover image of which featured newspaper clippings of the stock market section with a single match taped to the inlay card. Not all 12 songs made it onto the final album—two were eventually included as B-sides, while three others never saw an official release.[13] Several record labels expressed interest, and the band eventually signed with Epic Records. Morello said, "Epic agreed to everything we asked—and they've followed through ... We never saw a[n] [ideological] conflict as long as we maintained creative control."[14]

1992–1994: Rage Against the Machine

editThe band's debut album, Rage Against the Machine, was released in November 1992. The cover featured Malcolm Browne's Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph of Thích Quảng Đức, a Vietnamese Buddhist monk, burning himself to death in Saigon in 1963 in protest of the murder of Buddhists by the regime of the U.S.-backed prime minister Ngô Đình Diệm's. The album was produced by Canadian record producer and music engineer Garth Richardson.[15]

While sales were initially slow,[16] the album became a critical and commercial success, driven by heavy radio airplay of the song "Killing in the Name", a heavy, driving track featuring only eight lines of lyrics.[17][18] The "Fuck You" version, which contains 17 instances of the word fuck, was once accidentally played on the BBC Radio 1 Top 40 singles show on February 21, 1993.[19][20] The band's profile soared following a performance at the Lollapalooza festival in mid-1993 tour; sales of Rage Against the Machine in the United States increased from 75,000 before Lollapalooza, to 400,000 by the end of the year.[16] The band also toured with Suicidal Tendencies in Europe, and House of Pain.[21] By April 1996, the album had sold over 1 million copies in the United States and 3 million copies worldwide.[16] It was certified triple platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in May 2000.[22]

Rage Against the Machine appeared on the soundtrack for the 1995 film Higher Learning with the song "Year of tha Boomerang". An early version of "Tire Me" also appeared in the movie. Subsequently, they re-recorded the song "Darkness" from their original demo for the soundtrack of The Crow (1994), while "No Shelter" appeared on the Godzilla soundtrack in 1998.[23]

1995–2000: Mainstream success

edit"Different band members have their different interests that they've been pursuing. But principally, the main reason for the delay between records was trying to find the right combination of our very diverse influences that would make a record that we were all happy with and that was great. That was a long process."

In late 1994, Rage Against the Machine took a hiatus from touring, sparking rumors that they had broken up.[24] According to an anonymous source reporting to MTV News, Rage Against the Machine had recorded 23 tracks with producer Brendan O'Brien in Atlanta starting in November 1994, and briefly broke up due to violent infighting in the band, before regrouping for the KROQ Weenie Roast in June 1995.[24] Morello later said there had been conflict over their musical direction, which were reconciled.[24][25]

The band eventually recorded their long-awaited follow-up album, Evil Empire, with O'Brien in November and December 1995.[24] Morello said that, as a result of the band's musical tensions, the album incorporated greater hip hop influences, describing its sound as a "middle ground between Public Enemy and the Clash".[25]

Evil Empire was released on April 16, 1996, and entered the Billboard 200 chart at number one, selling 249,000 copies in its first week.[26][27] It later rose to triple platinum status.[28] Rage Against the Machine performed "Bulls on Parade" on Saturday Night Live in April 1996. Their planned two-song performance was cut to one song when the band attempted to hang inverted American flags from their amplifiers ("a sign of distress or great danger"),[29] in protest of the program's guest host, Republican presidential candidate Steve Forbes.[29]

In 1997, the band opened for U2 on the PopMart Tour. Their profits went to organizations[30] such as the Union of Needletrades, Industrial and Textile Employees, Women Alive and the Zapatista Front for National Liberation.[31] Rage began an abortive headlining U.S. tour with Wu-Tang Clan. Police in several jurisdictions unsuccessfully attempted to have the concerts cancelled, citing amongst, other reasons, the bands' "violent and anti-law enforcement philosophies".[32] After Wu-Tang Clan failed to appear during a concert at Riverport, they were removed from the lineup and replaced with the Roots. Sony Records released Live & Rare, compiling B-sides and live performances, in Japan in June 1998. A live video, Rage Against the Machine, was released later the same year.[21]

In 1999, Rage Against the Machine played at the Woodstock '99 concert. Their third album, The Battle of Los Angeles, debuted at number one in 1999, selling 450,000 copies in the first week and was certified double-platinum.[33] That year, the song "Wake Up" was featured on the soundtrack of the film The Matrix. The track "Calm Like a Bomb" was used in the sequel, The Matrix Reloaded (2003). In 2000, the band planned to support the Beastie Boys on the "Rhyme and Reason" tour, but the tour was cancelled when the Beastie Boys drummer, Mike D, suffered a serious injury.[34] In 2003, The Battle of Los Angeles was ranked number 426 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[35]

2000–2001: Breakup

editOn January 26, 2000, during filming of the video for "Sleep Now in the Fire", directed by Michael Moore, an altercation caused the doors of the New York Stock Exchange to be closed and the band to be escorted from the site by security[36] after band members attempted to gain entry into the exchange.[37] The video shoot had attracted several hundred people, according to a representative for the city's Deputy Commissioner for Public Information.[38] New York City's film office does not allow weekday film shoots on Wall Street. Moore had permission to use the steps of Federal Hall National Memorial but did not have a permit to shoot on the sidewalk or the street, nor did he have a loud-noise permit or the proper parking permits.[39] "Michael basically gave us one directorial instruction, 'No matter what happens, don't stop playing'", Tom Morello recalls. When the band left the steps, police officers apprehended Moore and led him away. Moore yelled to the band, "Take the New York Stock Exchange!"[40] In an interview with the Socialist Worker, Morello said he and scores of others ran into the Stock Exchange. "About two hundred of us got through the first set of doors, but our charge was stopped when the Stock Exchange's titanium riot doors came crashing down."[41] Moore said: "For a few minutes, Rage Against the Machine was able to shut down American capitalism, an act that I am sure tens of thousands of downsized citizens would cheer."[36]

On September 7, 2000, the band performed "Testify" at the 2000 MTV Video Music Awards.[42][43] After the Best Rock Video award was given to Limp Bizkit, Commerford climbed onto the scaffolding of the set.[42][43] He and his bodyguard were sentenced to a night in jail and De la Rocha reportedly left the awards after the stunt.[42][43] Morello recalled that Commerford relayed his plan to the rest of the band before the show, and that both De la Rocha and Morello advised him against it immediately after Bizkit was presented the award.[42][43]

On October 18, 2000, De la Rocha announced that he had left the band.[44] He said, "I feel that it is now necessary to leave Rage because our decision-making process has completely failed. It is no longer meeting the aspirations of all four of us collectively as a band, and from my perspective, has undermined our artistic and political ideal."[44] Morello said, "There was so much squabbling over everything, "and I mean everything. We would even have fist fights over whether our T-shirts should be mauve or camouflaged! It was ridiculous. We were patently political, internally combustible. It was ugly for a long time."[45] De la Rocha's departure was voted the "shittiest thing" of 2000 in the Kerrang! readers' poll of that year.[46]

The band's next album, Renegades, was a collection of covers of artists as diverse as Devo, EPMD, Minor Threat, Cypress Hill, the MC5, Afrika Bambaataa, the Rolling Stones, Eric B. & Rakim, Bruce Springsteen, the Stooges, and Bob Dylan.[33][47] It achieved platinum status a month later.[28] The following year saw the release of another live video, The Battle of Mexico City, while 2003 brought the live album Live at the Grand Olympic Auditorium, an edited recording of the band's final concerts on September 12 and 13, 2000, at the Grand Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles.[48] It was accompanied by an expanded DVD release of the last show, which included a previously unreleased video for "Bombtrack".[49]

In the wake of the September 11 attacks, the controversial 2001 Clear Channel memorandum contained a long list of what the memo termed "lyrically questionable" songs for the radio, uniquely listing all of Rage Against the Machine's songs.[50]

2002—2006: Side projects

editAfter the breakup, Morello, Wilk, and Commerford decided to stay together and find a new vocalist.[45] "There was talk for a while of us becoming Ozzy Osbourne's backing band, and even Macy Gray's," said Morello. "We informed [Epic Records] that losing our singer was actually a blessing in disguise, and that we had bigger ambitions than being somebody's hired musicians."[45] Their friend, the producer Rick Rubin, suggested they play with Chris Cornell of Soundgarden. Along with Cornell, they formed Audioslave.[51] Their first single, "Cochise", was released in November 2002, and their self-titled debut album followed to mainly positive reviews. In contrast to Rage Against the Machine, most of Audioslave's music was apolitical, although some songs touched on political issues. Their second album, Out of Exile debuted at the number one position on the Billboard charts in 2005.[52] Audioslave released its third album Revelations on September 4, 2006, but did not tour as Cornell and Morello were working on solo albums. After months of inactivity and rumors of a breakup, Audioslave disbanded on February 15, 2007, after Cornell announced he was leaving the band "due to irresolvable personality conflicts as well as musical differences".[53]

In 2003, Morello began playing acoustic folk music at open-mic nights and clubs under the alias the Nightwatchman, which he formed as an outlet for his political views while playing apolitical music with Audioslave. He participated in Billy Bragg's Tell Us the Truth tour[54] with no plans to record,[55] but recorded a song for Songs and Artists that Inspired Fahrenheit 9/11, "No One Left". In April 2007, he released an album, One Man Revolution,[56] followed by The Fabled City on September 30, 2008. Morello and the rapper Boots Riley formed the rap rock group Street Sweeper Social Club, and released their debut self-titled album in June 2009.[citation needed]

De la Rocha had been working on an album with DJ Shadow, Company Flow, Roni Size and Questlove,[44] but dropped the project in favor of working with Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails.[57] The album was not released.[58] A collaboration between De la Rocha and DJ Shadow, the song "March of Death" was released free online in 2003 in protest of the imminent invasion of Iraq.[59] The 2004 soundtrack Songs and Artists that Inspired Fahrenheit 9/11 included one of the collaborations with Reznor, "We Want It All".[57] In late 2005, De la Rocha performed with the son jarocho band Son de Madera, singing and playing the jarana huasteca.[60]

The band refused large sums of money to reunite for concerts and tours.[61] Rumors of tension between De la Rocha and the others circulated. Commerford said that he and De la Rocha saw each other often and went surfing together. Morello said he and De la Rocha communicated by phone, and had met at a 2005 protest in support of the South Central Farm.[62]

2007–2008: First reunion and tours

editOn April 14, 2007, Morello and De la Rocha reunited to perform a brief acoustic set at a Coalition of Immokalee Workers rally in downtown Chicago. Morello described the event as "very exciting for everybody in the room, myself included".[63] Rage Against the Machine reunited to headline the final day of the 2007 Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival on April 29, in front of an EZLN backdrop to the largest crowds of the festival.[64][65][66] Morello said they reunited to voice their opposition to the "right-wing purgatory" the United States had "slid into" under the George W. Bush administration since their dissolution.[67]

Rage Against the Machine continued to tour in the United States, New Zealand, Australia, and Japan.[68] They played a series of shows in Europe in 2008, including Rock am Ring and Rock im Park, Pinkpop Festival, T in the Park in Scotland, the Hultsfred Festival in Sweden, the Reading and Leeds Festivals in England and the Oxegen Festival in Ireland. They also performed on August 2 in Chicago at the 2008 Lollapalooza festival.

Morello said they had no plans to record a new album, and said: "Writing and recording albums is a whole different thing than getting back on the bike ... But I think that the one thing about the Rage catalog is that to me none of it feels dated. You know, it doesn't feel at all like a nostalgia show. It feels like these are songs that were born and bred to be played now."[69] De la Rocha said," As far as us recording music in the future, I don't know where we all fit with that. We've all embraced each other's projects and support them, and that's great."[70]

In July 2008, De la Rocha and the drummer Jon Theodore, formerly of the Mars Volta, released an EP as One Day as a Lion.[71] In August 2008, during the Democratic National Convention in Denver, Rage headlined the free Tent State Music Festival to End the War. They were supported by Flobots, State Radio, Jello Biafra, and Wayne Kramer.[72] Following the concert, the band, following uniformed veterans from the advocacy group Iraq Veterans Against the War, led the 8,000 attendees to the Denver Coliseum on a six-mile march to Invesco Field, host of the DNC. After a four-hour stand-off with police, the Obama campaign agreed to meet with members of Iraq Veterans Against the War and hear their demands.[73]

In September 2008, Rage performed at the Target Center in Minneapolis during the Republican National Convention. The previous day, they attempted to play a surprise set at a free anti-RNC concert at the Minnesota Capitol in St. Paul, but were prevented by the police. Instead, De la Rocha and Morello rapped and sang through a megaphone. Later that evening, Morello and Boots Reilly joined the songwriter Billy Bragg and the politician Jim Walsh for a three-hour jam session at Pepitos Parkway theater in south Minneapolis.[citation needed] In December 2008, Morello said his Nightwatchman project would be his "principal musical focus, as I see it, for the remainder of my life".[74] He repeated this point in an interview with the Los Angeles Times.[75]

2009–2015: UK "Killing in the Name" Christmas campaign, European tour, and L.A. Rising

editIn December 2009, a campaign was launched on Facebook by Jon Morter and his wife Tracy, in order to stop, most notably, The X Factor hits from becoming almost automatic Christmas number ones on the UK Singles Chart. It generated nationwide publicity and took the track "Killing in the Name" to the coveted Christmas number one slot in the UK Singles Chart, which had been dominated for four consecutive years from 2005 by winners from the popular TV show The X Factor.[76] Before the chart was announced on December 20, 2009, the Facebook group membership stood at over 950,000, and was acknowledged (and supported) by Tom Morello,[77] Dave Grohl,[78] Paul McCartney,[79] Muse, Fightstar,[80] NME, John Lydon,[67] Bill Bailey,[67] Lenny Henry,[67] BBC Radio 1,[81] Hadouken!,[82] the Prodigy,[83] Stereophonics,[83] BBC Radio 5 Live,[84] and even the 2004 X Factor winner Steve Brookstein,[85] amongst numerous others. On the morning of December 17, Rage Against the Machine played a slightly censored version of "Killing in the Name" live on Radio 5 Live, but four repeats of 'Fuck you I won't do what you tell me' were aired before the song was pulled.[86] During the interview before the song they reiterated their support for the campaign and their intentions to support charity with the proceeds. The campaign was ultimately successful, and "Killing in the Name" became the number-one single in the UK for Christmas 2009.[87][88] Zack de la Rocha spoke to BBC One upon hearing the news, stating that:

We're very very ecstatic and excited about the song reaching the number one spot. We want to thank everyone that participated in this incredible, organic, grass-roots campaign. It says more about the spontaneous action taken by young people throughout the UK to topple this very sterile pop monopoly. When young people decide to take action they can make what's seemingly impossible, possible.[88]

The band also set a new record, achieving the biggest download sales total in a first week ever in the UK charts.[88] De la Rocha also promised the band would perform a free concert in the UK sometime in 2010 to celebrate the achievement.[88] True to their word, the band announced that they would be performing a free concert at Finsbury Park, London, on June 6, 2010.[89] The concert, dubbed "The Rage Factor", gave away all the tickets by free photo registration to prevent touting over the weekend of the February 13–14, followed by an online lottery on February 17. This proved to be popular, with many users facing connection issues. The tickets were all allocated by 13:30 that same day.[90] After allowing ticket holders to vote for who they wanted to be the support acts for "The Rage Factor", it was announced that Gogol Bordello, Gallows and Roots Manuva would support Rage Against the Machine at the concert.[91]

In addition to the free gig at Finsbury Park, the band headlined European festivals in June 2010 including the Download Festival at Donington Park, England, Rock am Ring and Rock im Park in Germany and Rock in Rio Madrid in Spain.[92] They also performed in Ireland on June 8 and the Netherlands on June 9. Zack de la Rocha had stated that it was a definite possibility that the band would record a new album, the first time since 2000's Renegades.[93] Morter confirmed this, stating the discussions he and the band had backstage before the Finsbury Park gig saying the band did write new material, but they had no motivation to release them until now. De la Rocha mentioned the very strong reaction from the Download Festival 2010 audience as an incentive for releasing new material.[94] In addition, the band returned to Los Angeles on July 23, 2010, for their first U.S. show in two years and their first hometown show in 10 years.[95] The concert benefited Arizona organizations that are fighting the SB1070 immigration law. On the night of the show, a spokesperson announced to the crowd that ticket sales—all of which are non-profit to the bands—had raised $300,000. The band has been confirmed to do a short South American tour in October, performing at venues such as the SWU Festival in Brazil, the Maquinaria Festival in Chile, and Pepsi Music Festival in Argentina. It was the first time the band played in those countries.

After the "Rage Factor" celebratory show in Finsbury Park in London on June 6, 2010, after the campaign to get "Killing in the Name" to the No. 1 spot at Christmas, Zack de la Rocha stated that it was a "genuine possibility". Stating that they may use the momentum from the campaign to get back into the studio and write a follow-up record to 2000's Renegades after 10 years. When talking to NME, Zack de la Rocha said: "I think it's a genuine possibility, We have to get our heads around what we're going to do towards the end of the year and finish up on some other projects and we'll take it from there."[96]

During an interview with the Chilean newspaper La Tercera in October 2010, De la Rocha allegedly confirmed that a new album was in the works, with a possibility of a 2011 release. De la Rocha is reported as saying, "We are all bigger and more mature and we do not fall into the problems we faced 10 or 15 years ago. This is different and we project a lot: we are working on a new album due out next year, perhaps summer for the northern hemisphere".[97] However, in early May 2011, guitarist Tom Morello said that the band was not working on a new album, but would not rule out the possibility of future studio work. "The band is not writing songs, the band is not in the studio", Morello told The Pulse of Radio. "We get along famously and we all, you know, intend to do more Rage Against the Machine stuff in the future, but beyond sort of working out a concert this year, there's nothing else on the schedule (for 2011)".[89] The band created its own festival, the L.A. Rising. As Morello stated, the only Rage Against the Machine appearance for 2011 was a performance on July 30 at the L.A. Rising festival with El Gran Silencio, Immortal Technique, Lauryn Hill, Rise Against and Muse.[89] During an interview on July 30, 2011, Commerford seemingly contradicted Morello's comments, stating that new material was being written, and specific plans for the next two years were in place.[98]

In an October 2012 interview with TMZ, bassist Tim Commerford was asked if Rage Against the Machine was working on a new album. He simply responded, "maybe".[99] Asked by TMZ again in November 2012 whether a new album was being worked on, Commerford replied "definitely maybe ... anything's possible".[100] Later that month, however, Morello denied that they were working on new material, and stated that Rage Against the Machine had "no plans beyond" the reissue of their self-titled debut album.[101] Morello said he would be open to recording new Rage Against the Machine material, but added that it was "not on the table right now".[102]

The band announced on October 9 via their Facebook page that they would be releasing a special 20th anniversary box set to commemorate the group's debut album. The full box set contains never-before-released concert material, including the band's 2010 Finsbury Park show and footage from early in their career, as well as a digitally-remastered version of the album, b-sides and the original demo tape (on disc for the first time).[103][104] The band released 3-disc and single-disc versions.[105] The collection was released on November 27.[104]

In an April 2014 interview with The Pulse of Radio, drummer Brad Wilk indicated that, as far as he knew, Rage Against the Machine's 2011 performance at L.A. Rising was their final show.[106] In February 2015, Tim Commerford said that uncertainty over when they might play again was typical of the band's functioning, speculating: "It could be tomorrow; it could be 10 years from now".[107]

On October 16, 2015, the 2010 gig in Finsbury Park was released as a DVD and Blu-ray called Live at Finsbury Park.

2016–2019: Prophets of Rage

editIn May 2016, the band launched a countdown website, prophetsofrage.com, with a clock counting down to June 1. Accompanying the clock was an image of a broken slash through a circle with silhouettes of five people all extending their arms and clenched fists with the hashtag "#takethepowerback" underneath the timer. This led to speculation of the return of the band later in the year. However, a source close to Rage Against the Machine told Rolling Stone that the Prophets of Rage website had nothing do with the announcement of a "Rage-specific reunion", but added that "some of the members" of the band were working on a project that would include live shows.[108] It was later confirmed that Prophets of Rage were a new supergroup formed by Morello, Wilk and Commerford, with Chuck D of Public Enemy and B-Real of Cypress Hill.[109] The band toured through the remainder of 2016 and played the songs of the three bands in which the members of this group participated in before.[110]

Despite Morello, Wilk and Commerford's commitments to Prophets of Rage, the latter confirmed in a May 2016 interview with Rolling Stone that Rage Against the Machine had not split up, explaining, "We just do things our own way. Throughout our career, we never did what anyone wanted us to do. We never made the records people wanted us to make. We never played by the rules people wanted us to play by. And here we are, 25 years later, still a band. Clearly that means something. And if we did ever play or make new music or anything, it would be a very big deal. And there's a lot of bands that I've seen come along during that 25-year period that did everything the record companies and the powers-that-be wanted them to do, and they sold millions of records. But where are they now? They're gone."[111] Morello added, "Right now ... the cold embers of Rage Against the Machine are now the burning fire of Prophets of Rage. Where Rage Against the Machine lives, is this summer in these songs that we are playing. And we have nothing but the greatest love and honor and respect for Zack de la Rocha, the brilliant lyricist of Rage Against the Machine, who is working on his own music, which I'm sure will be fantastic—he's a great artist in his own right. But where you're going to hear Rage Against the Machine is in Prophets of Rage."[112]

In May 2018, Wilk stated that "nothing would make him happier" than if the band was to reunite, but stated "it's just really a matter of getting us all on the same page".[113] In November 2019, Chuck D and B-Real confirmed that Prophets of Rage had disbanded.[114]

2019–2024: Second reunion, Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction and third disbandment

editOn November 1, 2019, it was reported that Rage Against the Machine were reuniting for their first shows in nine years in the spring of 2020, including two appearances at that year's Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival.[115][116][117] On November 25, 2019, an alleged leaked tour poster made its way online indicating the band would be going on a world tour throughout 2020. This was later debunked by Australian-based publication Wall of Sound who broke the news that a concert poster troll photoshopped and released it online as a prank.[118][119]

On February 10, 2020, Rage Against the Machine announced more worldwide dates for the 2020 reunion tour, now named the Public Service Announcement Tour.[120][121] It was scheduled to run from March 26 through September 12, making it the band's first full-length world tour in 20 years, after they completed the promotional cycle for their third album The Battle of Los Angeles.[120][121] The supporting act on all shows but Chicago would be rap duo Run the Jewels.[121] On March 12, 2020, the band postponed the first leg of the reunion tour due to the COVID-19 pandemic;[122] this tour was eventually postponed to the summer of 2021.[123] On May 1, 2020, the band announced that they had rescheduled the remaining dates of their reunion tour to 2021.[124] They were also due to headline the Reading and Leeds Festivals, which would have been Rage Against the Machine's first UK appearance in ten years, but it was announced on May 12, 2020, that the festival was cancelled.[125] Despite having rescheduled all of their tour dates, Rage Against the Machine was initially still scheduled to play Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival, which had been postponed from April to October 2020 before it was officially cancelled that June.[123][126] On April 8, 2021, it was announced that the Public Service Announcement Tour had once again been rescheduled to the spring and summer of 2022.[127]

By June 11, 2020, every Rage Against the Machine album had entered the top 30 of Apple Music's Rock Albums chart, and their debut album had entered the Billboard Top 200 at number 174.[128] The resurgence of interest in the band's music and politics was widely attributed to renewed worldwide Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis by law enforcement.[129][130][131]

On July 9, 2022, Rage Against the Machine played their first concert in 11 years at Alpine Valley Music Theatre in East Troy, Wisconsin.[132] After De la Rocha ruptured his Achilles tendon during a show in Chicago in July,[133] Rage Against the Machine canceled their European tour and their remaining North American tour dates.[134][135]

Rage Against the Machine was nominated for induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in their first year of eligibility in 2017, and again in 2018, 2019, and 2021.[136][137] They were inducted on November 3, 2023, by Ice-T, at Barclays Center in Brooklyn.[138] Only Morello attended the ceremony.[139] On January 3, 2024, Wilk confirmed that Rage Against the Machine had disbanded again.[140][141]

Musical style and influences

editInspired by early heavy metal instrumentation, Rage Against the Machine has been influenced by a variety of music, including acts like Rush, Led Zeppelin, Bob Dylan, U2, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Iron Maiden, Kiss, Black Sabbath/Ozzy Osbourne, the Police, Devo, Living Colour, Queen, the Brothers Johnson and Wayne Shorter.[142][143] They are also said to be influenced by hip hop acts such as Afrika Bambaataa,[33] Run-DMC, Public Enemy, and the Beastie Boys, punk rock such as the Clash, Minor Threat, the Teen Idles,[142] Bad Brains, the Dead Kennedys, Black Flag,[144] the Sex Pistols,[142] Fugazi[145] and Bad Religion,[142] and crossover bands like Suicidal Tendencies[146] and Urban Dance Squad.[147]

Rage Against the Machine has been noted for its "fiercely polemical music, which brewed sloganeering leftist rants against corporate America, cultural imperialism, and government oppression into a Molotov cocktail of punk rock, hip hop, and thrash."[33]

Zack de la Rocha's lyrics and choruses are defined by a heavy use of sloganeering and repetition on songs like "Bulls on Parade", "Guerrilla Radio", "Testify", and "Down Rodeo". Guitarist Tom Morello was also considered the DJ of the group.[148]

Rage Against the Machine has been described as rap metal, rap rock, funk metal, fusion, alternative metal, hard rock, nu metal, and alternative rock.[note 1] Although the band has been described as nu metal, Rage Against the Machine is often instead considered a predecessor to nu metal.[182][183][184]

Political views and activism

editThe members of Rage Against the Machine are well known for their leftist anti-authoritarian and revolutionary political views, and almost all of the band's songs focus on these views. Key to the band's identity, Rage Against the Machine has voiced viewpoints highly critical of the domestic and foreign policies of current and previous U.S. governments. Throughout its existence, Rage Against the Machine and its individual members participated in political protests and other activism to advocate these beliefs. The band sees its music as a vehicle for social activism; De la Rocha explained, "I'm interested in spreading those ideas through art, because music has the power to cross borders, to break military sieges and to establish real dialogue."[185]

Morello said of wage slavery in America:

America touts itself as the land of the free, but the number one freedom that you and I have is the freedom to enter into a subservient role in the workplace. Once you exercise this freedom you've lost all control over what you do, what is produced, and how it is produced. And in the end, the product doesn't belong to you. The only way you can avoid bosses and jobs is if you don't care about making a living. Which leads to the second freedom: the freedom to starve.[186]

Some critics have accused the group of hypocrisy for voicing commitment to leftist causes while being millionaires signed to Epic Records, a subsidiary of media conglomerate Sony Music.[187] Infectious Grooves released a song called "Do What I Tell Ya!" which mocks lyrics from "Killing in the Name", accusing the band of being hypocrites.[188][189] In response to such critiques, Morello stated:

When you live in a capitalistic society, the currency of the dissemination of information goes through capitalistic channels. Would Noam Chomsky object to his works being sold at Barnes & Noble? No, because that's where people buy their books. We're not interested in preaching to just the converted. It's great to play abandoned squats run by anarchists, but it's also great to be able to reach people with a revolutionary message, people from Granada Hills to Stuttgart.[14]

De la Rocha stated:

Yeah, to get as many people as possible to join the political debate, to get the dialogue going. I was wondering today, why would anyone climb to the roof of the American Embassy with a banner that says "Free Mumia Abu-Jamal", why do you do that? That's to get the international press' attention. The international network that Sony has available, is to me the perfect tool you know, it can get even more people to join a revolutionary awareness and fight.[190]

For their 2020 reunion tour, the band announced all profits from their first three shows—in El Paso, Texas; Las Cruces, New Mexico; and Glendale, Arizona—would be donated to immigrant rights organizations in the US. For subsequent shows, 10% of the base ticket price and 100% of proceeds after fees and base ticket price were reserved for charities local to each city they were performing in.[191][192]

In May 2021, more than 600 musicians, including Rage Against the Machine, added their signature to the open letter calling for a boycott of performances in Israel until the occupation of the Palestinian territories comes to an end.[193] Zack de la Rocha and Tom Morello voiced support for a ceasefire in the 2023 Israel–Hamas war.[194][195][196]

On June 24, 2022, the band announced that they would donate $475,000 to reproductive rights groups in Wisconsin and Illinois after the Supreme Court's ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade.[197] During their July 9 concert in Wisconsin, the band further expressed opposition to overturning of Roe v. Wade using screened images of text including "Abort the Supreme Court" and "Forced birth in a country where black birth-givers experience maternal mortality two to three times higher than that of white birth-givers. Forced birth in a country where gun violence is the number one cause of death among children and teenagers."[198]

Members

edit- Zack de la Rocha – lead vocals (1991–2000, 2007–2011, 2019–2024)

- Tom Morello – guitars (1991–2000, 2007–2011, 2019–2024)

- Tim Commerford – bass, backing vocals (1991–2000, 2007–2011, 2019–2024)

- Brad Wilk – drums, percussion (1991–2000, 2007–2011, 2019–2024)

Discography

editStudio albums

- Rage Against the Machine (1992)

- Evil Empire (1996)

- The Battle of Los Angeles (1999)

- Renegades (2000)

Awards and nominations

editRage Against the Machine has won two Grammy Awards with six nominations altogether.[199] Rage Against the Machine was ranked 33rd on VH1's 100 Greatest Artists of Hard Rock list in 2005.[8] In 2008, they were inducted into the Kerrang! "Hall of Fame", and in 2010 they won NME's Heroes of the Year Award.[200][201] The band has also received three nominations from the MTV Video Music Awards, but has never won an award.[202][203][204] Rage Against The Machine have been nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018, 2019 and 2021.[205]

In 2021, the UK Official Charts Company announced that "Killing in the Name" had been named as the 'UK's Favourite Christmas Number 1 of All Time'[206] in a poll commissioned to celebrate the 70th Official Christmas Number 1 race (and as a tie-in with the book The Official Christmas No. 1 Singles Book by Michael Mulligan).[207][208]

Grammy Awards

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | "Tire Me" | Best Metal Performance[209] | Won |

| "Bulls on Parade" | Best Hard Rock Performance[209][210] | Nominated | |

| 1998 | "People of the Sun" | Nominated | |

| 1999 | "No Shelter" | Best Metal Performance[199] | Nominated |

| 2001 | "Guerrilla Radio" | Best Hard Rock Performance[199] | Won |

| The Battle of Los Angeles | Best Rock Album[199] | Nominated | |

| 2002 | "Renegades of Funk" | Best Hard Rock Performance[199] | Nominated |

MTV Video Music Awards

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | "Bulls on Parade" | Best Rock Video[202][203][204] | Nominated |

| 1997 | "People of the Sun" | Nominated | |

| 2000 | "Sleep Now in the Fire" | Nominated |

NME Awards

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Rage Against the Machine | Heroes of the Year[201] | Won |

Kerrang! Awards

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | Rage Against the Machine | Hall of Fame[200] | Won |

Classic Rock Roll of Honour Awards

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Rage Against the Machine | Band of the Year[211] | Nominated |

| Christmas Number One and Free Concert | Event of the Year[212] | Won |

Rock and Roll Hall of Fame

| Year | Nominee / work | Award | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Rage Against the Machine | Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[213] | Nominated |

| 2019 | Rage Against the Machine | Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[213] | Nominated |

| 2021 | Rage Against the Machine | Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[213] | Nominated |

| 2022 | Rage Against the Machine | Rock and Roll Hall of Fame[213] | Nominated |

| 2023 | Rage Against the Machine | Rock and Roll Hall of Fame [214] | Won |

Notes

edit- ^ Musical styles:

References

edit- ^ Berdini, Valerio (June 9, 2010). "live on 35mm.Berdini,Valerio". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011.

- ^ "Kate Bush and Willie Nelson Among 2023 Rock Hall of Fame Inductees". www.vulture.com. May 3, 2023. Archived from the original on July 31, 2023. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- ^ "Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Reveals Class of 2023: Willie Nelson, Kate Bush, Missy Elliott, Sheryl Crow, Rage Against the Machine and More". www.variety.com. May 3, 2023.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. May 31, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums - Year-End [1996]". Billboard 200. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on April 27, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums - Year-End [1999]". Billboard 200. January 2, 2013. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Devenish, Colin (2001), Rage Against the Machine: St. Martin's Griffin ISBN 0-312-27326-6

- ^ a b "VH1: '100 Greatest Hard Rock Artists': 1-50". Rock On The Net. Archived from the original on February 14, 2002. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine Break Up...Again". Rolling Stone. January 4, 2024. Retrieved January 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c Myers, Ben (October 16, 1999), Hello, Hello... ...It's Good To Be Back Archived July 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Kerrang!. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- ^ Kielty, Martin (May 4, 2018). "Why Brad Wilk Failed Pearl Jam Audition". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2019.

- ^ McClard, Kent, History Archived February 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine of Ebullition Records. Retrieved February 19, 2007.

- ^ Woodlief, Mark. "Rage Against the Machine". TrouserPress.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ a b "Rage Against the Machine FAQ". Archived from the original on May 26, 2006., Internet Archive cache of FAQ on the official Rage Against the Machine website. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Rage Against the Machine – Rage Against the Machine". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 11, 2010. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ a b c Hilburn, Robert (April 14, 1996). "Up Against the Wall : You want raw, unfiltered extremism? You got it. Rage Against the Machine is back, with all pistons firing. The band members once thought they'd be too political for anyone to care. They were wrong". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 5, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine Gold and Platinum". RIAA. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Buckley, Peter (2003). The rough guide to rock. Rough Guides. p. 844. ISBN 978-1-84353-105-0. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Robinson, John (January 29, 2000). "The Revolution Will Not be Trivialised". NME. UK. Archived from the original on September 15, 2000. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "The History Of: Rage Against The Machine". Ultimate Guitar. July 27, 2007. Archived from the original on January 18, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ^ a b "h2g2 - Rage Against The Machine - the Band - A730883". BBC. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine | Gold & Platinum". RIAA. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ "h2g2 - Rage Against The Machine - the Band - A730883". BBC. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e MTV News Staff (January 22, 1996). "Evil Empire Due From Rage Against The Machine". MTV. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Vice, Jeff (September 6, 1996). "Rage still likes to use music in struggle for social change". The Deseret News. p. W5. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Mayfield, Geoff (November 20, 1999). "Between the Bulletins". Billboard. p. 134. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ MTV News Staff (May 3, 1996). "Rage Builds "Evil Empire"". MTV. Archived from the original on July 22, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Gold & Platinum — June 09, 2010". RIAA. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b "rage: SNL Incident". Musicfanclubs.org. Archived from the original on July 9, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "h2g2 - Rage Against The Machine - the Band - Edited Entry". BBC. Archived from the original on August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine and U2 Make a Perfect Duo" (newspaper article). The State. Archived from the original on April 4, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Cooper, Matt (September 11, 1997). "Judge Gives Go-Ahead For Rage Concert Tomorrow At The Gorge" (newspaper article). Seattle Times. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Ankeny, Jason (2004). "Rage Against the Machine – Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "Really Randoms: Jessica Simpson, Oasis". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original (magazine article) on September 17, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "Rolling Stone – The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time (2003)". Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ a b "Rage against Wall Street". Green Left Weekly #397. March 15, 2000. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ Basham, David (January 28, 2000). "Rage Against the Machine Shoots New Video With Michael Moore". MTV News. Archived from the original on March 13, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine Shoots New Video With Michael Moore". MTV News. January 28, 2000. Archived from the original on October 9, 2015. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ Shone, Mark (May 1, 2000). "Bullsh*t on Parade: Rage Against The Machine and Michael Moore Battle New York Cops". SPIN. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (2011). 33 Revolutions Per Minute. Faber & Faber.

- ^ Devenish, C. (2001). Rage Against The Machine. St. Martin's Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-4299-2514-3. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Mapes, Jillian; Letkemann, Jessica (September 9, 2010). "MTV Loves MTV: A Bad Romance". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d MTV news (September 3, 2010). "The 2010 VMA Countdown: Rage Against The Machine Bassist Gets A Better Look At The Action". MTV.com. MTV Networks. Archived from the original on September 11, 2010. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c Armstrong, Mark (October 18, 2000). "Zack de la Rocha Leaves Rage Against the Machine". MTV News. Archived from the original on February 10, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c Q, May 2003, p60

- ^ Rees, Paul, ed. (January 13, 2001). "Readers' Poll 2000". Kerrang! (835). EMAP: 29–36.

- ^ "Rock & Roll: The Last Days of Rage? - With No Lead Singer, Rage Consider Their Next Move". ProQuest 1193001.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bush, John (2003). ""Live at the Grand Olympic Auditorium" – Overview". Allmusic. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- ^ Doyle, Patrick (November 21, 2012). "Rage Against the Machine Blast Through 'Bombtrack' in 1992 - Premiere". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 27, 2014. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Bertin, Michael (November 30, 2001). "Imagine: The music business in a post-911 world". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on June 22, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen. "Audioslave - Audioslave". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 8, 2012. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Harris, Chris (June 1, 2005). "Audioslave Rage To First Billboard No. 1". MTV News. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ Harris, Chris (February 15, 2007). "Chris Cornell Talks Audioslave Split, Nixes Rumors Of Soundgarden Reunion". MTV News. Archived from the original on August 17, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- ^ Wiederhorn, Jon (October 22, 2003). "Tom Morello Rages Against A New Machine On Solo Acoustic Tour". MTV News. Archived from the original on August 29, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Moss, Corey (July 29, 2004). "Audioslave's Morello Says New LP Feels Less Like Soundgarden + Rage". MTV News. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Harris, Chris (February 6, 2007). "Nightwatchman, Rage Reunion Have Morello Fired Up For Political Fights". MTV News. Archived from the original on February 19, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ a b Moss, Corey (May 10, 2005). "Reznor Says Collabos With de la Rocha, Keenan May Never Surface". MTV News. Archived from the original on April 29, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Gargano, Paul (October 2005). "Nine Inch Nails (interview)". Maximum Ink Music Magazine. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "March of Death". Archived from the original on February 25, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ "King of Rage Onstage Again" (February 2006), Spin. [full citation needed]

- ^ "Chris Cornell Working on Solo Release – But Dismisses Rumors of Audioslave Split". MTV News. Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Rockline interviews Audioslave. August 29, 2006.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine Guitarist Calls Rally Performance 'Very Exciting'". Launch Radio Networks. 93X Rock News. April 20, 2007. Archived from the original on April 21, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine reunite at Coachella". NME. UK. April 30, 2007. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Sulugiuc, Gelu (April 30, 2007). "Rage Against the Machine reunites". Yahoo! News. Reuters. Archived from the original on May 3, 2007. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ Moss, Corey (April 30, 2007). "Rage Against the Machine's Ferocious Reunion Caps Coachella's Final Night". MTV News. Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "NME". NME. UK. Archived from the original on April 13, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine tour announced". Fasterlouder.com.au. September 19, 2007. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "Tom Morello: 'No Plans' For New Rage Against the Machine Album". Blabbermouth.net. Ultimateguitar.com. May 1, 2007. Archived from the original on January 12, 2009. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ^ "Zack de la Rocha talks to Ann Powers". Los Angeles Times. August 11, 2008. Archived from the original on August 12, 2011.

- ^ Tao, Paul (July 1, 2008). "Anti Records Signs One Day as a Lion". Absolutepunk.net. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ Jefferson, Elana (August 27, 2008). "Review: Rage Against the Machine". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ Riccardi, Nicholas; Correll, DeeDee (August 28, 2008). "Protest led by Iraq war veterans ends in talk with Obama liaison - Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ^ Graff, Gary (December 5, 2008). "Morello: Nightwatchman Takes Priority Over Rage". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2009.

- ^ Martens, Todd (April 1, 2009). "Tom Morello at the Grammy Museum: Political activism, music biz lessons and what about another Rage album?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine to take on 'The X Factor' for Christmas Number One". New Musical Express. December 4, 2009. Archived from the original on December 5, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2009.

- ^ "Twitter / Tom Morello: Rage's Killing in the Name". Twitter. December 14, 2009. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Dave Grohl: 'I'm Buying Rage Against the Machine'". Gigwise. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on April 27, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ Daniel Kreps (December 18, 2009). "Paul McCartney Backs Rage Against the Machine in U.K. Battle | Music News". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 19, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2011.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine for Christmas no 1! It's already at no 2! Stop X Factor stealing the top spot again! Buy 'killing in the name of'!". Official Fightstar Facebook. December 14, 2009. Archived from the original on September 22, 2008. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- ^ "Broadcast Yourself". YouTube. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ HadoukenUK (December 13, 2009). "Just bought my Rage Against The Machine single". Twitter. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b 12/15/09 5:57pm by Mark Teo (CHARTattack). "Chartattack.com". Chartattack.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Rage Against 5 Live.wmv". YouTube. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on September 7, 2012. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Kerrang! Former X Factor winner backs Rage campaign!". .kerrang.com. Archived from the original on December 14, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "BBC Radio 5 live - 5 live Breakfast, 17/12/2009". BBC. December 17, 2009. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Singles Top 40 from the Official UK Charts Company". Theofficialcharts.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d "– Rage Against the Machine beat X Factor winner in charts". BBC News. December 20, 2009. Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Rage Against the Machine Announces Free U.K. Gig Details". Blabbermouth.net. February 12, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine's free London gig: all tickets allocated | News". NME. UK. February 17, 2010. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine Announce 'Rage Factor' Support Acts". Gigwise. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Download Festival 2010". Downloadfestival.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 18, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ O'Neal, Sean. "Rage Against the Machine considering recording new album". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "Rock Radio". Downloadfestivalradio.com. June 14, 2010. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine and Conor Oberst to Play Concert to Benefit Arizona Organizations Fighting SB1070". thesoundstrike.net (Press release). July 14, 2010. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- ^ Slater, Luke (June 7, 2010). "New Rage Against The Machine record "a possibility" / Music News // Drowned In Sound". Drownedinsound. Archived from the original on November 9, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Zach de la Rocha: Vamos a Chile para tributar el legado de Bolaño y Víctor Jara". La Tercera (in Spanish). October 3, 2010. Archived from the original on May 10, 2018. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- ^ Vadala, Nick (August 2, 2011). "Rage Against The Machine Bassist Tim Commerford Says New Material in the Works, Next Two Years Planned Out | mxdwn.com News". Mxdwn.com. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine -- New Album In The Works ... Maybe". TMZ. October 4, 2012. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2012.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine Bassist -- Paul Ryan's a Dumbass for Liking Our Music". TMZ. November 3, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- ^ Graff, Gary (November 15, 2012). "Rage Against the Machine: 'No Plans' to Record New Album". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 4, 2013. Retrieved November 16, 2012.

- ^ "Tom Morello: Not Everybody In Rage Against the Machine Wants To Make New Album". Blabbermouth.net. November 22, 2012. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine". Facebook. January 6, 1983. Archived from the original on May 10, 2018. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ a b "Rage Against The Machine XX 20th Anniversary | Rage Against The Machine Official Site". Ratm.com. July 9, 2012. Archived from the original on October 7, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine - XX (20th Anniversary Special Edition)(2 CD/ 1 DVD): Music". Amazon. Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine Drummer Brad Wilk Says Band May Have Already Played Its Last Show". Blabbermouth.net. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2014.

- ^ "Timmy C. speaks about Rage's future". musicradar.com. February 9, 2015. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ "Fans Expecting Imminent Rage Against The Machine Reunion Will Be Disappointed". Blabbermouth.net. May 18, 2016. Archived from the original on August 10, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ Chris Payne (May 18, 2016). "Rage Against the Machine, Public Enemy & Cypress Hill Members Form Supergroup: Sources". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ Young, Alex (May 18, 2016). "Rage Against the Machine, Public Enemy, and Cypress Hill members form new supergroup". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on August 23, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine, Public Enemy & Cypress Hill Members Unite In Prophets Of Rage | Theprp.com – Metal And Hardcore News Plus Reviews And More". Theprp.com. May 31, 2016. Archived from the original on September 10, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Tom Morello: "The Cold Embers Of Rage Against The Machine Are Now The Burning Fire Of Prophets Of Rage" | Theprp.com – Metal And Hardcore News Plus Reviews And More". Theprp.com. May 31, 2016. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2016.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine drummer calls for reunion: "Nothing would make me happier" - NME". NME. May 3, 2018. Archived from the original on May 4, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (November 2, 2019). "Prophets of Rage Rappers Acknowledge Rage Against the Machine Reunion". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- ^ Baltin, Steve (November 1, 2019). "Confirmed: Rage Against The Machine To Reunite In 2020, Headline Coachella". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ Hartmann, Graham (November 1, 2019). "Rage Against the Machine Announce 2020 Reunion". Loudwire. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ Brooks, Dave (November 1, 2019). "Rage Against the Machine to Reunite for 2020 Coachella". Billboard. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved November 1, 2019.

- ^ "UPDATE: That Rage Against The Machine Tour Poster Is FAKE!". Wall Of Sound. November 24, 2019. Archived from the original on November 25, 2019. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Moore, Sam (November 25, 2019). "That Rage Against The Machine tour poster that's doing the rounds is fake". NME. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ a b Martoccio, Angie (February 10, 2020). "Rage Against the Machine Announce 2020 Tour". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Rage Against the Machine Announce Reunion Tour: See the Dates". Billboard. February 10, 2020. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved June 5, 2020.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (March 13, 2020). "Rage Against the Machine Postpone First Half of Reunion Tour Due to Coronavirus". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 19, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Kreps, Daniel (May 2, 2020). "Rage Against the Machine Reschedule Reunion Tour for 2021". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 2, 2020. Retrieved May 2, 2020.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine Reschedule Reunion Tour". Lambgoat.com. Lambgoat. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved May 5, 2020.

- ^ "Reading and Leeds festivals cancelled". BBC News. May 12, 2020. Archived from the original on May 13, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Yoo, Noah (June 11, 2020). "Coachella 2020 Canceled Due to COVID-19". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (April 8, 2021). "Rage Against the Machine Postpone Reunion Tour to 2022". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 8, 2021. Retrieved April 9, 2021.

- ^ Elvish, Emily (June 13, 2020). "20 years since their last release, Rage Against the Machine are back in the charts". Happy Mag. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Schaffner, Lauryn (June 12, 2020). "Rage Against the Machine Re-Enter Charts Amidst Social Unrest". Loudwire. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Rolli, Bryan (June 11, 2020). "Rage Against The Machine Returns To Billboard 200 And iTunes Top 10 Amid Nationwide Protests, Conservative Backlash". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Kaufman, Spencer (June 12, 2020). "Rage Against the Machine Re-enter Charts as Protests Rage On". Consequence of Sound, CoS. Archived from the original on April 24, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ Greene, Andy (July 10, 2022). "Rage Against The Machine Roar Back to Life at Explosive Reunion Tour Launch". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ^ Monroe, Jazz (August 11, 2022). "Rage Against the Machine Cancel European Tour, Per "Medical Guidance" for Zack de la Rocha". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 11, 2022. Retrieved August 11, 2022.

- ^ Schaffner, Lauryn (August 15, 2022). "RATM's Zack de la Rocha Reportedly Suffering From Torn Achilles". Loudwire. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Millman, Ethan (October 4, 2022). "Rage Against the Machine Cancel North American Tour". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ France, Lisa Respers (October 5, 2017). "Rock and Roll Hall of Fame 2018 nominees announced". CNN. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017.

- ^ Trepany, Charles (March 2, 2021). "Rock & Roll Hall of Fame sets date, venue for 2021 inductions after going virtual in 2020". USA Today. Archived from the original on January 16, 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ "Rock & Roll Hall of Fame: Kate Bush, George Michael among Class of 2023". MSN.

- ^ "TOM MORELLO Was Only Member of RAGE AGAINST THE MACHINE Present at Band's ROCK HALL Induction". November 4, 2023.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (January 3, 2024). "Rage Against the Machine Will Not Tour Again, Brad Wilk Says". Pitchfork. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ Greene, Andy (January 3, 2024). "Rage Against the Machine Break Up… Again". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "The Roots Of ... Rage Against The Machine - NME". NME. July 18, 2013. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ Sutcliffe, Phil (2015). Queen, Revised Updated: the Ultimate Illustrated History of the Crown Kings of Rock. Voyageur Press. p. 3.

- ^ Hill, Stephen (July 2017). "Guerilla Radio 25 Years of Raging". Metal Hammer. p. 42.

- ^ Heller, Jason (December 7, 2012). "The strange rehabilitation of Rage Against The Machine". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017.

- ^ Shawn Costa (October 13, 2016). "Review: Megadeth, Suicidal Tendencies and Amon Amarth rock Worcester's DCU Center (Photos)". The Republican. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2019.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Urban Dance Squad – Biography". Metrolyrics. Archived from the original on November 3, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Guitar World Lesson With Tom Morello (RATM, Audioslave)". Youtube. May 16, 2011. Archived from the original on October 21, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Bienstock, Richard (November 1, 2017). "6 Things You Didn't Know About 'Rage Against the Machine". Revolver Magazine. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Hughes, Rob (February 12, 2019). "Story Behind the Song: Killing In The Name by Rage Against The Machine". Classic Rock. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Neilstein, Vince (March 6, 2010). "#9: Rage Against the Machine". Metal Sucks. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine: Christmas no 1 upset over X Factor 'cost bookies £1m'". Telegraph. December 21, 2009. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Klosterman, Chuck (September 14, 2010). Chuck Klosterman on Rock: A Collection of Previously Published Essays - Chuck Klosterman - Google Books. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451624496. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ McIver, Joel (December 15, 2008). The 100 Greatest Metal Guitarists - Joel McIver - Google Books. Jawbone Press. ISBN 9781906002206. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved February 19, 2015.

- ^ Hughes, Josiah (August 17, 2015). "Rage Against the Machine Ready 'Live at Finsbury Park' DVD". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Chris. "Rage Against the Machine - Rage Against the Machine Review". BBC. Archived from the original on January 25, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (May 27, 2010). "Rage Against the Machine lead Arizona boycott". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Heaney, Gregory. "Rage Against the Machine - The Collection". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Powers, Ann (December 31, 2000). "Music; No Last Hurrah Yet for Political Rock". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Stevens, Anne; O’Donnell, Molly (2020). The Microgenre: A Quick Look at Small Culture. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 167. ISBN 9781501345838. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

Funk metal (late 1980s) employs the distinctive sound of funk; conventional riffing is similar to 1980s thrash metal (Red Hot Chili Peppers, Living Colour, Primus and Rage Against the Machine)

- ^ a b "Rage Against the Machine Take a Test Run Through 'Freedom' – Premiere". Rollingstone. November 19, 2019. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Catucci, Nick (November 27, 2012). "Rage Against the Machine – XX". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. Archived from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ "The Battle Of Los Angeles". NME. IPC Media. October 26, 1999. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

another album of ranting, churning, slamming heavy funk-metal thunder like this one.

- ^ Turman, Katherine (June 8, 1992). "Review: 'Liquid Jesus; East of Gideon; Rage Against the Machine'". Variety. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

Group's approach is an intellectual-urban, multi-ethnic funk-metal hybrid, heavy on the bouncy energy

- ^ Le Roux, Maxime (February 11, 2020). "Rage Against the Machine ..." HuffPost (in French). AFP. Archived from the original on September 1, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022. [Rock en Seine announced the presence of the fusion band for the last day of its 2020 festival]

- ^ Chevalier, François; Maire, Jérémie (May 19, 2016). "Pogo, fusion et poing levé: ..." [Moshing, fusion and raised fist: Rage Against the Machine in six furious tracks]. Télérama (in French). Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Weissman, Dick (2010). Talkin' 'Bout a Revolution: Music and Social Change in America. Backbeat Books. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-4234-4283-7. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Ferre, Robin; Thiriez, Igor; Yassef, Mathieu (2010). Camion Blanc: ... [White Truck: Riff Story from Hard Rock to Heavy Metal] (in French). Rosières-en-Haye. p. 263. ISBN 978-2-3577-9105-3. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022. [Musically, the formula [of System of a Down] oscillates between the fusion of Rage Against the Machine, the already dying nu metal combined with some alternative elements]

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Rage Against the Machine ..." Rolling Stone (in French). August 11, 2022. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ "Beams & Insonnia Projects Rework Vintage Rage Against the Machine T-Shirts". July 18, 2019. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Kraus, Brian (August 18, 2012). "Tom Morello chastises Paul Ryan for being a Rage Against The Machine fan". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Grierson, Tim. "Alternative Metal". About.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2016. Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ "Alternative Metal". Allmusic. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved July 18, 2016.

- ^ Young, Alex (May 18, 2016). "Rage Against the Machine, Public Enemy, and Cypress Hill members form new supergroup". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Appleford, Steve (July 26, 2010). "Rage Against the Machine Rock for Immigrants' Rights". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Taylor, Jerome (December 20, 2009). "Rage Against the Machine take Christmas No.1 slot – News, Music – The Independent". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on February 22, 2010. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ McIver, Joel (2001). Slipknot Unmasked. Omnibus Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-7119-8677-0. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ^ Witmer, Scott (2010). History of Rock Bands. ABDO. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-60453-692-8.

rage against the machine nu metal.

- ^ Taylor, Sam (September 3, 2000). "America's 'nu metal' bands have the world at their feet". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ Cooper, Ali (December 21, 2021). "20 nü-metal bands that defined the late '90s and early 2000s". Alternative Press. Archived from the original on July 22, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Ives, Brian (October 9, 2019). "Rage Against the Machine, Def Leppard, More Nominated for Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". Loudwire. Archived from the original on September 23, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ Nihill, Bill (October 25, 2013). "The Best Selling Heavy Metal Albums of All Time in the U.S." Metal Descent. Archived from the original on October 4, 2017. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ^ Arnopp, Jason (2011). Slipknot: Inside the Sickness, Behind the Masks With an Intro by Ozzy Osbourne and Afterword by Gene Simmons. Random House. ISBN 9781446458341.

If Rage had paved the way for nu-metal, Korn defined it.

- ^ Udo, Tommy (2002). Brave Nu World. Sanctuary Publishing. pp. 15, 42–43, 244. ISBN 1-86074-415-X.

- ^ Wooldridge, Simon (February 2000), "Fight the Power Archived February 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine", Juice Magazine. Retrieved October 6, 2007.

- ^ Young, Charles M. (February 1997), Tom Morello: Artist of the Year interview Archived August 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Guitar World. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ "Rage On: The strange politics of millionaire rock stars". Reason Online. Archived from the original on August 31, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- ^ "Suicidal Tendencies Frontman On Rumored Gang Affiliation, Being Only Original Member". Roadrunnerrecords.com. November 26, 2008. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (1995). The Guinness encyclopedia of popular music. Guinness Pub. ISBN 9781561591763. Archived from the original on April 27, 2023. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ "the complete RATM site". Musicfanclubs.org. Archived from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ Wallis, Adam. "Expensive Rage Against the Machine tickets are for charity, says guitarist Tom Morello". Global News. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (February 14, 2020). "How Rage Against the Machine Are Trying to Beat Scalpers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on March 27, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ "Rage Against the Machine, Roger Waters, Serj Tankian, among many to boycott Israel". The Business Standard. June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Rage Against The Machine's Tom Morello condemns harm to all children after Jamie Lee Curtis Gaza pic". Euronews. October 12, 2023.

- ^ "Zack de la Rocha skips Rock Hall Induction to Attend March for Palestine". Phoenix Music Magazine. November 9, 2023.

- ^ "Musicians for Palestine: Thousands of musicians sign letter for Gaza ceasefire". Euronews. November 23, 2023.

- ^ Iasimone, Ashley (June 25, 2022). "Rage Against the Machine Donates $475K to Reproductive Rights Organizations Following Roe v. Wade Ruling". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved June 26, 2022.

- ^ Draughorne, Kenan (July 11, 2022). "Rage Against the Machine reunites with a potent message: 'Abort the Supreme Court'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 11, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Rage Against the Machine". Grammy.com. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b "Kerrang! Awards: Metallica, Slipknot and Rage Against The Machine honoured". The Telegraph. August 22, 2008. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Fullerton, Jamie (February 25, 2010). "Rage Against The Machine win Hero Of The Year Shockwaves NME award". NME. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b "1996 MTV Video Music Awards". Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b "Beck, Jamiroquai Lead Video Music Awards Nominees". MTV. July 22, 2018. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Herman, Maureen (September 8, 2000). "Rage Against the Machine Explain Bassist's Actions". Rollingstone. Archived from the original on June 16, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ "Who are the next Rock & Roll Hall of Famers?". Future Rock Legends. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ "UK's favourite Christmas No. 1 of all time revealed". OfficialCharts.com. Archived from the original on December 16, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ Official Charts Company/Nine Eight Books ISBN 9781788705851

- ^ "The British obsession with the Christmas number one single – SuperDeluxeEdition". December 12, 2021. Archived from the original on December 16, 2021. Retrieved December 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Campbell, Mary (January 8, 1997). "Babyface is up for 12 Grammy awards". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. p. 8B. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Mary (January 7, 1998). "Grammys' dual Dylans". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Journal Communications. p. 8B. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

- ^ "AC/DC up for Classic Rock award". BBC. August 13, 2010. Archived from the original on June 19, 2018. Retrieved June 16, 2018.