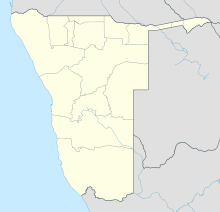

The Rössing uranium mine in Namibia is the longest-running and one of the largest open pit uranium mines in the world. It is located in the Namib Desert near the town of Arandis, 70 kilometres from the coastal town of Swakopmund. Discovered in 1928, the Rössing mine started operations in 1976. In 2005, it produced 3,711 tonnes of uranium oxide, becoming the fifth-largest uranium mine with 8 per cent of global output. Namibia is the world's fourth-largest exporter of uranium.[1]

| |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Location | Namib Desert |

| Region | Erongo |

| Country | |

| Coordinates | 22°29′03″S 015°02′56″E / 22.48417°S 15.04889°E |

| Production | |

| Products | Uranium |

| History | |

| Opened | 1976 |

| Owner | |

| Company | Rössing Uranium Limited (Rio Tinto Group, Iran, Namibia) |

| Website | Rossing.com |

In the apartheid era, the mine was the focus of international criticism and protests by anti-apartheid and anti-nuclear groups, mainly in Europe.[2] Reports that Rössing's uranium might be diverted to Iran, whose government owns 15% of the shares in the mine via its Iranian Foreign Investment Company, have been denied by the mine's management which maintains that the shareholding is entirely passive.[3][4]

Mine operations

editBackground

editUranium was discovered in the Namib Desert in 1928 but explorations began only at the end of the 1950. Rössing is the largest of three mines exploiting Uranium in the Namib, the others are Langer Heinrich operated by Paladin, and Husab, under Chinese ownership. The open pit mine's production capacity is 4,500 tons.[5]

Extraction

editRössing is a low-grade ore body of huge extent. Producing 1,000 tonnes of uranium oxide requires processing of 3 million tonnes of ore, and in 2005 19.5 million tonnes of rock were mined and transported from the open pit to the processing plant. Of those, 12 million tonnes were uranium ore, which in turn required 226,276 tonnes of acid for processing into yellowcake, a powdered uranium concentrate which is the basis for nuclear reactor fuel.[1]

There are some fears that salt and uranium from the mine is endangering the farming industry in the Swakop River area. Rössing is working with the Namibian farmers on this issue.[6][7]

A catastrophic structural failure of a leach tank resulted in a major spill at Rössing on 3 December 2013.[8] The France-based laboratory, CRIIRAD, reported elevated levels of radioactive materials in the area surrounding the mine.[9][10] Workers were not informed of the dangers of working with radioactive materials and the health effects thereof.[11][12][13]

Ownership

editFollowing Rio Tinto's 2018 sale of Rössing shares to China National Uranium Corporation (CNUC), CNUC became the majority owner of Rössing with a 68.6% equity stake.[14]: 205–206 15% of Rössing is held by the Government of Iran (purchased in 1976), 10% by IDC of South Africa, 3% by the Government of Namibia (with 51% of voting rights), and 3% by local individual shareholders.[15] Although Rössing's part-ownership by Iran was the cause of controversy in the 1970s and 1980s, the Namibian Government – in power since 1990 – has denied supplying Iran with Namibian uranium, which could be used for nuclear weapons.[16]

Employment

editRössing Uranium is one of the largest employers in Namibia's Erongo Region. About 800 people were employed at the mine in 2005, of whom 96% are Namibians. Of these, 160 worked in the open pit, 186 in the processing plant, 267 engineering and 200 administrative personnel.[1] Total employment increased to 1,528 in 2012, with an additional 780 jobs provided through subcontractors. For 2013, 276 staff are to be laid off.[5] Most of the workers live in the mining settlement of Arandis or in nearby Swakopmund. Critics[who?] have argued that the mine has a history of racial discrimination against its black employees (a common feature of apartheid-era companies), including harsh disciplinary measures, abominable housing conditions at Arandis, and low wages. Even with substantial improvements in the '90s after Namibia's independence, blacks and their unions still claim being disadvantaged.[17]

For 2006 and 2007 the mine management has announced investment of about US$112 million, mostly on mining equipment such as haul trucks and shovels, as well as on updating the processing plant. The main target is to increase uranium oxide production to the mine's full planned capacity of 4,000 tonnes. Expansion plans are expected to extend the mine's life to at least 2016. The possibility of underground mining has been explored in the past, and stated to have the possibility of extending the life of the mine for several further decades.[18]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Rössing (from infomine.com, status Friday 30 September 2005)

- ^ Opposition Outside Namibia Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (from the Gulliver Rössing Uranium Ltd Dossier)

- ^ Duddy, Jo-Maré (3 February 2010). "Nam uranium spooks the US". The Namibian.

- ^ "Rössing reviews Iranian shareholding after lifting of sanctions". New Era. 26 January 2016. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ a b Kaira, Chamwe (11 June 2013). "Rössing steers another storm". The Namibian. pp. 10–11. Archived from the original on 20 June 2013. Some of the factual statements are only available in the offline version of this article.

- ^ Uranium in groundwater 'not serious': Roessing – The Namibian, Friday 24 June 2005

- ^ "Rössing in the Erongo Region". Rössing Uranium Limited. Archived from the original on 30 December 2006. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ^ WISE Uranium Project. "Issues at Rössing Uranium Mine, Namibia". World Information Service on Energy, Uranium Project. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Commission de Recherche et d’Information Indépendantes sur la Radioactivité. "Preliminary results of CRIIRAD radiation monitoring near uranium mines in Namibia" (PDF). 11 April 2012. CRIIRAD. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Commission de Recherche et d’Information Indépendantes sur la Radioactivité. "CRIIRAD Preliminary Report No. 12-32b Preliminary results of radiation monitoring near uranium mines in Namibia" (PDF). 5 April 2012. CRIIRAD EJOLT Project. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2016. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Labor Resource and Research Institute. "Namibian workers in times of uncertainty: The Labour Movement 20 years after independence". 2009. LaRRI. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ LaRRI. "Our Work: Labour Resource and Research Institute". 25 April 2013. LaRII. Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Shinbdondola-Mote, Hilma (January 2009). "Uranium mining in Namibia: The mystery behind 'low level radiation'". Labor Resource and Research Institute (LaRRI). Retrieved 7 April 2014.

- ^ Massot, Pascale (2024). China's Vulnerability Paradox: How the World's Largest Consumer Transformed Global Commodity Markets. New York, NY, United States of America: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-777140-2.

- ^ "Rössing's business at a glance – 2007". Rössing Uranium Limited. Archived from the original on 6 June 2009. Retrieved 10 May 2009.

- ^ Maletsky, Christof (1 February 2005). "Iran did not buy uranium from Rössing, says Govt". The Namibian. Archived from the original on 10 February 2005. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Rossing conditions Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (from the Gulliver Rossing Uranium Ltd Dossier)

- ^ Origins and development Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (from the Gulliver Rossing Uranium Ltd Dossier)

External links

edit- Rossing Mine (company website)

- Rossing Mine (from infomine.com, includes links to detailed info, satellite images, property map)

- The Gulliver File: Rossing Uranium Ltd Dossier Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (from SEA-US, an Australian anti-nuclear initiative, last revised 1997)