In quantum computing, a qubit (/ˈkjuːbɪt/) or quantum bit is a basic unit of quantum information—the quantum version of the classic binary bit physically realized with a two-state device. A qubit is a two-state (or two-level) quantum-mechanical system, one of the simplest quantum systems displaying the peculiarity of quantum mechanics. Examples include the spin of the electron in which the two levels can be taken as spin up and spin down; or the polarization of a single photon in which the two spin states (left-handed and the right-handed circular polarization) can also be measured as horizontal and vertical linear polarization. In a classical system, a bit would have to be in one state or the other. However, quantum mechanics allows the qubit to be in a coherent superposition of multiple states simultaneously, a property that is fundamental to quantum mechanics and quantum computing.

Etymology

editThe coining of the term qubit is attributed to Benjamin Schumacher.[1] In the acknowledgments of his 1995 paper, Schumacher states that the term qubit was created in jest during a conversation with William Wootters.

Bit versus qubit

editA binary digit, characterized as 0 or 1, is used to represent information in classical computers. When averaged over both of its states (0,1), a binary digit can represent up to one bit of Shannon information, where a bit is the basic unit of information. However, in this article, the word bit is synonymous with a binary digit.

In classical computer technologies, a processed bit is implemented by one of two levels of low direct current voltage, and whilst switching from one of these two levels to the other, a so-called "forbidden zone" between two logic levels must be passed as fast as possible, as electrical voltage cannot change from one level to another instantly.

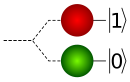

There are two possible outcomes for the measurement of a qubit—usually taken to have the value "0" and "1", like a bit. However, whereas the state of a bit can only be binary (either 0 or 1), the general state of a qubit according to quantum mechanics can arbitrarily be a coherent superposition of all computable states simultaneously.[2] Moreover, whereas a measurement of a classical bit would not disturb its state, a measurement of a qubit would destroy its coherence and irrevocably disturb the superposition state. It is possible to fully encode one bit in one qubit. However, a qubit can hold more information, e.g., up to two bits using superdense coding.

A bit is always completely in either one of its two states, and a set of n bits (e.g. a processor register or some bit array) can only hold a single of its 2n possible states at any time. A quantum state can be in a superposition, which means that the qubit can have non-zero probability amplitude in its both states simultaneously (popularly expressed as "it can be in both states simultaneously"). A qubit requires two complex numbers to describe its two probability amplitudes, and these two complex numbers can together be viewed as a 2-dimensional complex vector, which is called a quantum state vector, or superposition state vector. Alternatively and equivalently, the value stored in a qubit can be described as a single point in a 2-dimensional complex coordinate space. Similarly, a set of n qubits, which is also called a register, requires 2n complex numbers to describe its superposition state vector.[3][4]: 7–17 [2]: 13–17

Standard representation

editIn quantum mechanics, the general quantum state of a qubit can be represented by a linear superposition of its two orthonormal basis states (or basis vectors). These vectors are usually denoted as and . They are written in the conventional Dirac—or "bra–ket"—notation; the and are pronounced "ket 0" and "ket 1", respectively. These two orthonormal basis states, , together called the computational basis, are said to span the two-dimensional linear vector (Hilbert) space of the qubit.[5]

Qubit basis states can also be combined to form product basis states. A set of qubits taken together is called a quantum register. For example, two qubits could be represented in a four-dimensional linear vector space spanned by the following product basis states:

, , , and .

In general, n qubits are represented by a superposition state vector in 2n dimensional Hilbert space.[5]

Qubit states

editA pure qubit state is a coherent superposition of the basis states. This means that a single qubit ( ) can be described by a linear combination of and :

where α and β are the probability amplitudes, and are both complex numbers. When we measure this qubit in the standard basis, according to the Born rule, the probability of outcome with value "0" is and the probability of outcome with value "1" is . Because the absolute squares of the amplitudes equate to probabilities, it follows that and must be constrained according to the second axiom of probability theory by the equation[4]

The probability amplitudes, and , encode more than just the probabilities of the outcomes of a measurement; the relative phase between and is for example responsible for quantum interference, as seen in the double-slit experiment.

Bloch sphere representation

editIt might, at first sight, seem that there should be four degrees of freedom in , as and are complex numbers with two degrees of freedom each. However, one degree of freedom is removed by the normalization constraint |α|2 + |β|2 = 1. This means, with a suitable change of coordinates, one can eliminate one of the degrees of freedom. One possible choice is that of Hopf coordinates:

Additionally, for a single qubit the global phase of the state has no physically observable consequences,[a] so we can arbitrarily choose α to be real (or β in the case that α is zero), leaving just two degrees of freedom:

where is the physically significant relative phase.[7][b]

The possible quantum states for a single qubit can be visualised using a Bloch sphere (see picture). Represented on such a 2-sphere, a classical bit could only be at the "North Pole" or the "South Pole", in the locations where and are respectively. This particular choice of the polar axis is arbitrary, however. The rest of the surface of the Bloch sphere is inaccessible to a classical bit, but a pure qubit state can be represented by any point on the surface. For example, the pure qubit state would lie on the equator of the sphere at the positive X-axis. In the classical limit, a qubit, which can have quantum states anywhere on the Bloch sphere, reduces to the classical bit, which can be found only at either poles.

The surface of the Bloch sphere is a two-dimensional space, which represents the observable state space of the pure qubit states. This state space has two local degrees of freedom, which can be represented by the two angles and .

Mixed state

editA pure state is fully specified by a single ket, a coherent superposition, represented by a point on the surface of the Bloch sphere as described above. Coherence is essential for a qubit to be in a superposition state. With interactions, quantum noise and decoherence, it is possible to put the qubit in a mixed state, a statistical combination or "incoherent mixture" of different pure states. Mixed states can be represented by points inside the Bloch sphere (or in the Bloch ball). A mixed qubit state has three degrees of freedom: the angles and , as well as the length of the vector that represents the mixed state.

Quantum error correction can be used to maintain the purity of qubits.

Operations on qubits

editThere are various kinds of physical operations that can be performed on qubits.

- Quantum logic gates, building blocks for a quantum circuit in a quantum computer, operate on a set of qubits (a register); mathematically, the qubits undergo a (reversible) unitary transformation described by multiplying the quantum gates unitary matrix with the quantum state vector. The result from this multiplication is a new quantum state vector.

- Quantum measurement is an irreversible operation in which information is gained about the state of a single qubit, and coherence is lost. The result of the measurement of a single qubit with the state will be either with probability or with probability . Measurement of the state of the qubit alters the magnitudes of α and β. For instance, if the result of the measurement is , α is changed to 0 and β is changed to the phase factor no longer experimentally accessible. If measurement is performed on a qubit that is entangled, the measurement may collapse the state of the other entangled qubits.

- Initialization or re-initialization to a known value, often . This operation collapses the quantum state (exactly like with measurement). Initialization to may be implemented logically or physically: Logically as a measurement, followed by the application of the Pauli-X gate if the result from the measurement was . Physically, for example if it is a superconducting phase qubit, by lowering the energy of the quantum system to its ground state.

- Sending the qubit through a quantum channel to a remote system or machine (an I/O operation), potentially as part of a quantum network.

Quantum entanglement

editAn important distinguishing feature between qubits and classical bits is that multiple qubits can exhibit quantum entanglement; the qubit itself is an exhibition of quantum entanglement. In this case, quantum entanglement is a local or nonlocal property of two or more qubits that allows a set of qubits to express higher correlation than is possible in classical systems.

The simplest system to display quantum entanglement is the system of two qubits. Consider, for example, two entangled qubits in the Bell state:

In this state, called an equal superposition, there are equal probabilities of measuring either product state or , as . In other words, there is no way to tell if the first qubit has value "0" or "1" and likewise for the second qubit.

Imagine that these two entangled qubits are separated, with one each given to Alice and Bob. Alice makes a measurement of her qubit, obtaining—with equal probabilities—either or , i.e., she can now tell if her qubit has value "0" or "1". Because of the qubits' entanglement, Bob must now get exactly the same measurement as Alice. For example, if she measures a , Bob must measure the same, as is the only state where Alice's qubit is a . In short, for these two entangled qubits, whatever Alice measures, so would Bob, with perfect correlation, in any basis, however far apart they may be and even though both can not tell if their qubit has value "0" or "1"—a most surprising circumstance that cannot be explained by classical physics.

Controlled gate to construct the Bell state

editControlled gates act on 2 or more qubits, where one or more qubits act as a control for some specified operation. In particular, the controlled NOT gate (or CNOT or CX) acts on 2 qubits, and performs the NOT operation on the second qubit only when the first qubit is , and otherwise leaves it unchanged. With respect to the unentangled product basis , , , , it maps the basis states as follows:

- .

A common application of the CNOT gate is to maximally entangle two qubits into the Bell state. To construct , the inputs A (control) and B (target) to the CNOT gate are:

and

After applying CNOT, the output is the Bell State: .

Applications

editThe Bell state forms part of the setup of the superdense coding, quantum teleportation, and entangled quantum cryptography algorithms.

Quantum entanglement also allows multiple states (such as the Bell state mentioned above) to be acted on simultaneously, unlike classical bits that can only have one value at a time. Entanglement is a necessary ingredient of any quantum computation that cannot be done efficiently on a classical computer. Many of the successes of quantum computation and communication, such as quantum teleportation and superdense coding, make use of entanglement, suggesting that entanglement is a resource that is unique to quantum computation.[8] A major hurdle facing quantum computing, as of 2018, in its quest to surpass classical digital computing, is noise in quantum gates that limits the size of quantum circuits that can be executed reliably.[9]

Quantum register

editA number of qubits taken together is a qubit register. Quantum computers perform calculations by manipulating qubits within a register.

Qudits and qutrits

editThe term qudit denotes the unit of quantum information that can be realized in suitable d-level quantum systems.[10] A qubit register that can be measured to N states is identical[c] to an N-level qudit. A rarely used[11] synonym for qudit is quNit,[12] since both d and N are frequently used to denote the dimension of a quantum system.

Qudits are similar to the integer types in classical computing, and may be mapped to (or realized by) arrays of qubits. Qudits where the d-level system is not an exponent of 2 cannot be mapped to arrays of qubits. It is for example possible to have 5-level qudits.

In 2017, scientists at the National Institute of Scientific Research constructed a pair of qudits with 10 different states each, giving more computational power than 6 qubits.[13]

In 2022, researchers at the University of Innsbruck succeeded in developing a universal qudit quantum processor with trapped ions.[14] In the same year, researchers at Tsinghua University's Center for Quantum Information implemented the dual-type qubit scheme in trapped ion quantum computers using the same ion species.[15]

Also in 2022, researchers at the University of California, Berkeley developed a technique to dynamically control the cross-Kerr interactions between fixed-frequency qutrits, achieving high two-qutrit gate fidelities.[16] This was followed by a demonstration of extensible control of superconducting qudits up to in 2024 based on programmable two-photon interactions.[17]

Similar to the qubit, the qutrit is the unit of quantum information that can be realized in suitable 3-level quantum systems. This is analogous to the unit of classical information trit of ternary computers.[18] Besides the advantage associated with the enlarged computational space, the third qutrit level can be exploited to implement efficient compilation of multi-qubit gates.[17][19][20]

Physical implementations

editAny two-level quantum-mechanical system can be used as a qubit. Multilevel systems can be used as well, if they possess two states that can be effectively decoupled from the rest (e.g., the ground state and first excited state of a nonlinear oscillator). There are various proposals. Several physical implementations that approximate two-level systems to various degrees have been successfully realized. Similarly to a classical bit where the state of a transistor in a processor, the magnetization of a surface in a hard disk and the presence of current in a cable can all be used to represent bits in the same computer, an eventual quantum computer is likely to use various combinations of qubits in its design.

All physical implementations are affected by noise. The so-called T1 lifetime and T2 dephasing time are a time to characterize the physical implementation and represent their sensitivity to noise. A higher time does not necessarily mean that one or the other qubit is better suited for quantum computing because gate times and fidelities need to be considered, too.

Different applications like quantum sensing, quantum computing and quantum communication use different implementations of qubits to suit their application.

The following is an incomplete list of physical implementations of qubits, and the choices of basis are by convention only.

Qubit storage

editIn 2008 a team of scientists from the U.K. and U.S. reported the first relatively long (1.75 seconds) and coherent transfer of a superposition state in an electron spin "processing" qubit to a nuclear spin "memory" qubit.[23] This event can be considered the first relatively consistent quantum data storage, a vital step towards the development of quantum computing. In 2013, a modification of similar systems (using charged rather than neutral donors) has dramatically extended this time, to 3 hours at very low temperatures and 39 minutes at room temperature.[24] Room temperature preparation of a qubit based on electron spins instead of nuclear spin was also demonstrated by a team of scientists from Switzerland and Australia.[25] An increased coherence of qubits is being explored by researchers who are testing the limitations of a Ge hole spin-orbit qubit structure.[26]

See also

edit- Ancilla bit

- Bell state, W state and GHZ state

- Bloch sphere

- Electron-on-helium qubit

- Physical and logical qubits

- Quantum register

- Two-state quantum system

- The elements of the group U(2) are all possible single-qubit quantum gates[27]

- The circle group U(1) define the phase about the qubits basis states

Notes

edit- ^ This is because of the Born rule. The probability to observe an outcome upon measurement is the modulus squared of the probability amplitude for that outcome (or basis state, eigenstate). The global phase factor is not measurable, because it applies to both basis states, and is on the complex unit circle so

Note that by removing it means that quantum states with global phase can not be represented as points on the surface of the Bloch sphere. - ^ The Pauli Z basis is usually called the computational basis, where the relative phase have no effect on measurement. Measuring instead in the X or Y Pauli basis depends on the relative phase. For example, will (because this state lies on the positive pole of the Y-axis) in the Y-basis always measure to the same value, while in the Z-basis results in equal probability of being measured to or .

Because measurement collapses the quantum state, measuring the state in one basis hides some of the values that would have been measurable the other basis; See the uncertainty principle. - ^ Actually isomorphic: For a register with qubits and

References

edit- ^ Schumacher, B. (1995). "Quantum coding". Physical Review A. 51 (4): 2738–2747. Bibcode:1995PhRvA..51.2738S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.51.2738. PMID 9911903.

- ^ a b Nielsen, Michael A.; Chuang, Isaac L. (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-107-00217-3.

- ^ Shor, Peter (1997). "Polynomial-Time Algorithms for Prime Factorization and Discrete Logarithms on a Quantum Computer∗". SIAM Journal on Computing. 26 (5): 1484–1509. arXiv:quant-ph/9508027. Bibcode:1995quant.ph..8027S. doi:10.1137/S0097539795293172. S2CID 2337707.

- ^ a b Williams, Colin P. (2011). Explorations in Quantum Computing. Springer. pp. 9–13. ISBN 978-1-84628-887-6.

- ^ a b Yanofsky, Noson S.; Mannucci, Mirco (2013). Quantum computing for computer scientists. Cambridge University Press. pp. 138–144. ISBN 978-0-521-87996-5.

- ^ Seskir, Zeki C.; Migdał, Piotr; Weidner, Carrie; Anupam, Aditya; Case, Nicky; Davis, Noah; Decaroli, Chiara; Ercan, İlke; Foti, Caterina; Gora, Paweł; Jankiewicz, Klementyna; La Cour, Brian R.; Malo, Jorge Yago; Maniscalco, Sabrina; Naeemi, Azad; Nita, Laurentiu; Parvin, Nassim; Scafirimuto, Fabio; Sherson, Jacob F.; Surer, Elif; Wootton, James; Yeh, Lia; Zabello, Olga; Chiofalo, Marilù (2022). "Quantum games and interactive tools for quantum technologies outreach and education". Optical Engineering. 61 (8): 081809. arXiv:2202.07756. Bibcode:2022OptEn..61h1809S. doi:10.1117/1.OE.61.8.081809. This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Nielsen, Michael A.; Chuang, Isaac (2010). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–16. ISBN 978-1-10700-217-3. OCLC 43641333.

- ^ Horodecki, Ryszard; et al. (2009). "Quantum entanglement". Reviews of Modern Physics. 81 (2): 865–942. arXiv:quant-ph/0702225. Bibcode:2009RvMP...81..865H. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.81.865. S2CID 59577352.

- ^ Preskill, John (2018). "Quantum Computing in the NISQ era and beyond". Quantum. 2: 79. arXiv:1801.00862. Bibcode:2018Quant...2...79P. doi:10.22331/q-2018-08-06-79. S2CID 44098998.

- ^ Nisbet-Jones, Peter B. R.; Dilley, Jerome; Holleczek, Annemarie; Barter, Oliver; Kuhn, Axel (2013). "Photonic qubits, qutrits and ququads accurately prepared and delivered on demand". New Journal of Physics. 15 (5): 053007. arXiv:1203.5614. Bibcode:2013NJPh...15e3007N. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/15/5/053007. ISSN 1367-2630. S2CID 110606655.

- ^ As of June 2022 1150 uses versus 31 uses on in the quant-ph category of arxiv.org.

- ^ Kaszlikowski, Dagomir; Gnaciński, Piotr; Żukowski, Marek; Miklaszewski, Wieslaw; Zeilinger, Anton (2000). "Violations of Local Realism by Two Entangled N-Dimensional Systems Are Stronger than for Two Qubits". Physical Review Letters. 85 (21): 4418–4421. arXiv:quant-ph/0005028. Bibcode:2000PhRvL..85.4418K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4418. PMID 11082560. S2CID 39822693.

- ^ Choi, Charles Q. (2017-06-28). "Qudits: The Real Future of Quantum Computing?". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2017-06-29.

- ^ Ringbauer, Martin; Meth, Michael; Postler, Lukas; Stricker, Roman; Blatt, Rainer; Schindler, Philipp; Monz, Thomas (21 July 2022). "A universal qudit quantum processor with trapped ions". Nature Physics. 18 (9): 1053–1057. arXiv:2109.06903. Bibcode:2022NatPh..18.1053R. doi:10.1038/s41567-022-01658-0. ISSN 1745-2481. S2CID 237513730. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Fardelli, Ingrid (August 18, 2022). "Researchers realize two coherently convertible qubit types using a single ion species". Phys.org.

- ^ Goss, Noah; Morvan, Alexis; Marinelli, Brian; Mitchell, Bradley K.; Nguyen, Long B.; Naik, Ravi K.; Chen, Larry; Jünger, Christian; Kreikebaum, John Mark; Santiago, David I.; Wallman, Joel J.; Siddiqi, Irfan (2022-12-05). "High-fidelity qutrit entangling gates for superconducting circuits". Nature Communications. 13 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 7481. arXiv:2206.07216. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13.7481G. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-34851-z. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9722686. PMID 36470858.

- ^ a b Nguyen, Long B.; Goss, Noah; Siva, Karthik; Kim, Yosep; Younis, Ed; Qing, Bingcheng; Hashim, Akel; Santiago, David I.; Siddiqi, Irfan (2024-08-19). "Empowering high-dimensional quantum computing by traversing the dual bosonic ladder". Nature Communications. 15 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 7117. arXiv:2312.17741. Bibcode:2024NatCo..15.7117N. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51434-2. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 11333499. PMID 39160166.

- ^ Irving, Michael (2022-10-14). ""64-dimensional quantum space" drastically boosts quantum computing". New Atlas. Retrieved 2022-10-14.

- ^ Nguyen, L. B.; Kim, Y.; Hashim, A.; Goss, N.; Marinelli, B.; Bhandari, B.; Das, D.; Naik, R. K.; Kreikebaum, J. M.; Jordan, A.; Santiago, D. I.; Siddiqi, I. (16 January 2024). "Programmable Heisenberg interactions between Floquet qubits". Nature Physics. 20 (1): 240–246. arXiv:2211.10383. Bibcode:2024NatPh..20..240N. doi:10.1038/s41567-023-02326-7.

- ^ Chu, Ji; He, Xiaoyu; Zhou, Yuxuan; Yuan, Jiahao; Zhang, Libo; Guo, Qihao; Hai, Yongju; Han, Zhikun; Hu, Chang-Kang; Huang, Wenhui; Jia, Hao; Jiao, Dawei; Li, Sai; Liu, Yang; Ni, Zhongchu; Nie, Lifu; Pan, Xianchuang; Qiu, Jiawei; Wei, Weiwei; Nuerbolati, Wuerkaixi; Yang, Zusheng; Zhang, Jiajian; Zhang, Zhida; Zou, Wanjing; Chen, Yuanzhen; Deng, Xiaowei; Deng, Xiuhao; Hu, Ling; Li, Jian; Liu, Song; Lu, Yao; Niu, Jingjing; Tan, Dian; Xu, Yuan; Yan, Tongxing; Zhong, Youpeng; Yan, Fei; Sun, Xiaoming; Yu, Dapeng (2022-11-14). "Scalable algorithm simplification using quantum AND logic". Nature Physics. 19 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 126–131. arXiv:2112.14922. doi:10.1038/s41567-022-01813-7. ISSN 1745-2473.

- ^ Berrios, Eduardo; Gruebele, Martin; Shyshlov, Dmytro; Wang, Lei; Babikov, Dmitri (2012). "High fidelity quantum gates with vibrational qubits". Journal of Chemical Physics. 116 (46): 11347–11354. Bibcode:2012JPCA..11611347B. doi:10.1021/jp3055729. PMID 22803619.

- ^ Lucatto, B.; et al. (2019). "Charge qubit in van der Waals heterostructures". Physical Review B. 100 (12): 121406. arXiv:1904.10785. Bibcode:2019PhRvB.100l1406L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.100.121406. S2CID 129945636.

- ^ Morton, J. J. L.; et al. (2008). "Solid-state quantum memory using the 31P nuclear spin". Nature. 455 (7216): 1085–1088. arXiv:0803.2021. Bibcode:2008Natur.455.1085M. doi:10.1038/nature07295. S2CID 4389416.

- ^ Kamyar Saeedi; et al. (2013). "Room-Temperature Quantum Bit Storage Exceeding 39 Minutes Using Ionized Donors in Silicon-28". Science. 342 (6160): 830–833. arXiv:2303.17734. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..830S. doi:10.1126/science.1239584. PMID 24233718. S2CID 42906250.

- ^ Náfrádi, Bálint; Choucair, Mohammad; Dinse, Klaus-Pete; Forró, László (July 18, 2016). "Room temperature manipulation of long lifetime spins in metallic-like carbon nanospheres". Nature Communications. 7: 12232. arXiv:1611.07690. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712232N. doi:10.1038/ncomms12232. PMC 4960311. PMID 27426851.

- ^ Wang, Zhanning; Marcellina, Elizabeth; Hamilton, A. R.; Cullen, James H.; Rogge, Sven; Salfi, Joe; Culcer, Dimitrie (April 1, 2021). "Qubits composed of holes could be the trick to build faster, larger quantum computers". npj Quantum Information. 7 (1). arXiv:1911.11143. doi:10.1038/s41534-021-00386-2. S2CID 232486360.

- ^ Barenco, Adriano; Bennett, Charles H.; Cleve, Richard; DiVincenzo, David P.; Margolus, Norman; Shor, Peter; Sleator, Tycho; Smolin, John A.; Weinfurter, Harald (1995-11-01). "Elementary gates for quantum computation". Physical Review A. 52 (5). American Physical Society (APS): 3457–3467. arXiv:quant-ph/9503016. Bibcode:1995PhRvA..52.3457B. doi:10.1103/physreva.52.3457. ISSN 1050-2947. PMID 9912645. S2CID 8764584.

Further reading

edit- Nielsen, Michael A.; Chuang, Isaac (2000). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521632358. OCLC 43641333.

- Williams, Colin P. (2011). Explorations in Quantum Computing. Springer. ISBN 978-1-84628-887-6.

- Yanofsky, Noson S.; Mannucci, Mirco (2013). Quantum computing for computer scientists. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87996-5.

- A treatment of two-level quantum systems, decades before the term "qubit" was coined, is found in the third volume of The Feynman Lectures on Physics (2013 ebook edition), in chapters 9–11.

- A non-traditional motivation of the qubit aimed at non-physicists is found in Quantum Computing Since Democritus, by Scott Aaronson, Cambridge University Press (2013).

- An introduction to qubits for non-specialists, by the person who coined the word, is found in Lecture 21 of The science of information: from language to black holes, by Professor Benjamin Schumacher, The Great Courses, The Teaching Company (4 DVDs, 2015).

- A picture book introduction to entanglement, showcasing a Bell state and the measurement of it, is found in Quantum entanglement for babies, by Chris Ferrie (2017). ISBN 9781492670261.