The Ptolemaic Kingdom (/ˌtɒlɪˈmeɪ.ɪk/; Koinē Greek: Πτολεμαϊκὴ βασιλεία, romanized: Ptolemaïkḕ basileía)[6] or Ptolemaic Empire[7] was an Ancient Greek polity based in Egypt during the Hellenistic period.[8] It was founded in 305 BC by the Macedonian general Ptolemy I Soter, a companion of Alexander the Great, and ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty until the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC.[9] Reigning for nearly three centuries, the Ptolemies were the longest and final dynasty of ancient Egypt, heralding a distinctly new era for religious and cultural syncretism between Greek and Egyptian culture.[10]

Ptolemaic Kingdom Πτολεμαϊκὴ βασιλεία Ptolemaïkḕ basileía | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 305 BC–30 BC | |||||||||||

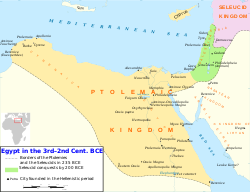

Ptolemaic Egypt c. 235 BC. The areas in green were lost to the Seleucid Empire thirty five years later. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Alexandria | ||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||

| Religion |

| ||||||||||

| Government | Hellenistic monarchy | ||||||||||

| Basileus/Pharaoh[3][4] | |||||||||||

• 305–283 BC | Ptolemy I Soter (first) | ||||||||||

• 51–30 BC | Cleopatra VII (last) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Classical antiquity | ||||||||||

• Established | 305 BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 30 BC | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 150 BC | 4.9–7.5 million[5] | ||||||||||

| Currency | Greek Drachma | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Alexander the Great conquered Persian-controlled Egypt in 332 BC during his campaigns against the Achaemenid Empire. His death in 323 BC was followed by rapid unraveling of the Macedonian Empire amid competing claims by the diadochi, his closest friends and companions. Ptolemy, a Macedonian who was one of Alexander's most trusted generals and confidants, won control of Egypt from his rivals and declared himself its ruler.[Note 1][11][12] Alexandria, a Greek polis founded by Alexander, became the capital city and a major center of Greek culture, learning, and trade for the next several centuries. Following the Syrian Wars with the Seleucid Empire, a rival Hellenistic state, the Ptolemaic Kingdom expanded its territory to include eastern Libya, the Sinai, and northern Nubia.

To legitimize their rule and gain recognition from native Egyptians, the Ptolemies adopted the local title of pharaoh,[9] alongside the Greek title of basileus,[3][4] and had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress; however, the monarchy otherwise rigorously maintained its Hellenistic character and traditions.[9] The kingdom had a complex government bureaucracy that exploited the country's vast economic resources to the benefit of a Greek ruling class, which dominated military, political, and economic affairs, and which rarely integrated into Egyptian society and culture. Native Egyptians maintained power over local and religious institutions, and only gradually accrued power in the bureaucracy, provided they Hellenized.[9] Beginning with Ptolemy I's son and successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the Ptolemies began to adopt Egyptian customs, such as marrying their siblings per the Osiris myth and participating in Egyptian religious life.[13] New temples were built, older ones restored, and royal patronage lavished on the priesthood.

From the mid third century BC, Ptolemaic Egypt was the wealthiest and most powerful of Alexander's successor states, and the leading example of Greek civilization.[9] Beginning in the mid second century BC, dynastic strife and a series of foreign wars weakened the kingdom, and it became increasingly reliant on the Roman Republic. Under Cleopatra VII, who sought to restore Ptolemaic power, Egypt became entangled in a Roman civil war, which ultimately led to its conquest by Rome as the last independent Hellenistic state. Roman Egypt became one of Rome's richest provinces and a center of Greek culture. Greek remained the language of government and trade until the Muslim conquest in 641 AD. Alexandria remained one of the leading cities of the Mediterranean well into the late Middle Ages.[14]

History

editThe Ptolemaic reign in Egypt is one of the best-documented time periods of the Hellenistic era, due to the discovery of a wealth of papyri and ostraca written in Koine Greek and Egyptian.[15]

Background

editIn 332 BC, Alexander the Great, King of Macedon, conquered Egypt, which at the time was a satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire later called Egypt's Thirty-first Dynasty.[16] He visited Memphis, and travelled to the oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis. The oracle declared him to be the son of Amun.

Alexander conciliated the Egyptians by the respect he showed for their religion, but he appointed Macedonians to virtually all the senior posts in the country, and founded a new Greek city, Alexandria, to be the new capital. The wealth of Egypt could now be harnessed for Alexander's conquest of the rest of the Achaemenid Empire. Early in 331 BC he was ready to depart, and led his forces away to Phoenicia. He left Cleomenes of Naucratis as the ruling nomarch to control Egypt in his absence. Alexander would never return to Egypt.

Establishment

editFollowing Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC,[17] a succession crisis erupted among his generals. Initially, Perdiccas ruled the empire as regent for Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, who became Philip III of Macedon, and then as regent for both Philip III and Alexander's infant son Alexander IV of Macedon, who had not been born at the time of his father's death. Perdiccas appointed Ptolemy, one of Alexander's closest companions, to be satrap of Egypt. Ptolemy ruled Egypt from 323 BC, nominally in the name of the joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV. However, as Alexander the Great's empire disintegrated, Ptolemy soon established himself as ruler in his own right. Ptolemy successfully defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas in 321 BC, and consolidated his position in Egypt and the surrounding areas during the Wars of the Diadochi (322–301 BC). In 305 BC, Ptolemy took the title of basileus and pharaoh.[3][4] As Ptolemy I Soter ("Saviour"), he founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that was to rule Egypt for nearly 300 years.

All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy, while princesses and female rulers preferred the names Cleopatra, Arsinoë and Berenice. The Ptolemies also adopted the Egyptian custom of marrying their sisters, with many of their line ruling jointly with their spouses, who were also of the royal house. This custom made Ptolemaic politics confusingly incestuous, and the later Ptolemies were increasingly feeble. The only basilissa-regnant or female Pharaohs to officially rule on their own were Cleopatra II, Berenice III and Berenice IV. Cleopatra V did co-rule, but it was with another female, Berenice IV. Cleopatra VII officially co-ruled with Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator, Ptolemy XIV, and Ptolemy XV, but effectively, she ruled Egypt alone.[18]

The early Ptolemies did not disturb the religion or the customs of the Egyptians.[19] They built magnificent new temples for the Egyptian gods and soon adopted the outward display of the pharaohs of old. Rulers such as Ptolemy I Soter respected the Egyptian people and recognized the importance of their religion and traditions. During the reign of Ptolemies II and III, thousands of Macedonian veterans were rewarded with grants of farm lands, and Macedonians were planted in colonies and garrisons or settled themselves in villages throughout the country. Upper Egypt, farthest from the centre of government, was less immediately affected, even though Ptolemy I established the Greek colony of Ptolemais Hermiou to be its capital. But within a century, Greek influence had spread through the country and intermarriage had produced a large Greco-Egyptian educated class. Nevertheless, the Greeks always remained a privileged minority in Ptolemaic Egypt. They lived under Greek law, received a Greek education, were tried in Greek courts, and were citizens of Greek cities.[20]

Rise

editPtolemy I

editThe first part of Ptolemy I's reign was dominated by the Wars of the Diadochi between the various successor states to the empire of Alexander. His first objective was to hold his position in Egypt securely, and secondly to increase his domain. Within a few years he had gained control of Libya, Coele-Syria (including Judea), and Cyprus. When Antigonus, ruler of Syria, tried to reunite Alexander's empire, Ptolemy joined the coalition against him. In 312 BC, allied with Seleucus, the ruler of Babylonia, he defeated Demetrius, the son of Antigonus, in the battle of Gaza.

In 311 BC, a peace was concluded between the combatants, but in 309 BC war broke out again, and Ptolemy occupied Corinth and other parts of Greece, although he lost Cyprus after a naval battle in 306 BC. Antigonus then tried to invade Egypt but Ptolemy held the frontier against him. When the coalition was renewed against Antigonus in 302 BC, Ptolemy joined it, but neither he nor his army were present when Antigonus was defeated and killed at Ipsus. He had instead taken the opportunity to secure Coele-Syria and Palestine, in breach of the agreement assigning it to Seleucus, thereby setting the scene for the future Syrian Wars.[21] Thereafter Ptolemy tried to stay out of land wars, but he retook Cyprus in 295 BC.

Feeling the kingdom was now secure, Ptolemy shared rule with his son Ptolemy II by Queen Berenice in 285 BC. He then may have devoted his retirement to writing a history of the campaigns of Alexander—which unfortunately was lost but was a principal source for the later work of Arrian. Ptolemy I died in 283 BC at the age of 84. He left a stable and well-governed kingdom to his son.

Ptolemy II

editPtolemy II Philadelphus, who succeeded his father as pharaoh of Egypt in 283 BC,[22] was a peaceful and cultured pharaoh, though unlike his father was no great warrior. Fortunately, Ptolemy I had left Egypt strong and prosperous; three years of campaigning in the First Syrian War made the Ptolemies masters of the eastern Mediterranean, controlling the Aegean islands (the Nesiotic League) and the coastal districts of Cilicia, Pamphylia, Lycia and Caria. However, some of these territories were lost near the end of his reign as a result of the Second Syrian War. In the 270s BC, Ptolemy II defeated the Kingdom of Kush in war, gaining the Ptolemies free access to Kushite territory and control of important gold deposits south of Egypt known as Dodekasoinos.[23] As a result, the Ptolemies established hunting stations and ports as far south as Port Sudan, from where raiding parties containing hundreds of men searched for war elephants.[23] Hellenistic culture would acquire an important influence on Kush at this time.[23]

Ptolemy II was an eager patron of scholarship, funding the expansion of the Library of Alexandria and patronising scientific research. Poets like Callimachus, Theocritus, Apollonius of Rhodes, Posidippus were provided with stipends and produced masterpieces of Hellenistic poetry, including panegyrics in honour of the Ptolemaic family. Other scholars operating under Ptolemy's aegis included the mathematician Euclid and the astronomer Aristarchus. Ptolemy is thought to have commissioned Manetho to compose his Aegyptiaca, an account of Egyptian history, perhaps intended to make Egyptian culture intelligible to its new rulers.[24]

Ptolemy's first wife, Arsinoe I, daughter of Lysimachus, was the mother of his legitimate children. After her repudiation he followed Egyptian custom and married his sister, Arsinoe II, beginning a practice that, while pleasing to the Egyptian population, had serious consequences in later reigns. The material and literary splendour of the Alexandrian court was at its height under Ptolemy II. Callimachus, keeper of the Library of Alexandria, Theocritus, and a host of other poets, glorified the Ptolemaic family. Ptolemy himself was eager to increase the library and to patronise scientific research. He spent lavishly on making Alexandria the economic, artistic and intellectual capital of the Hellenistic world. The academies and libraries of Alexandria proved vital in preserving much Greek literary heritage.

Ptolemy III Euergetes

editPtolemy III Euergetes ("the Benefactor") succeeded his father in 246 BC. He abandoned his predecessors' policy of keeping out of the wars of the other Macedonian successor kingdoms, and began the Third Syrian War (246–241 BC) with the Seleucid Empire when his sister, Queen Berenice, and her son were murdered in a dynastic dispute. Ptolemy marched into the heart of the Seleucid realm, as far as Babylonia, while his fleets in the Aegean Sea made fresh conquests as far north as Thrace.

This victory marked the zenith of the Ptolemaic power. Seleucus II Callinicus kept his throne, but Egyptian fleets controlled most of the coasts of Anatolia and Greece. After this triumph Ptolemy no longer engaged actively in war, although he supported the enemies of Macedon in Greek politics. His domestic policy differed from his father's in that he patronised the native Egyptian religion more liberally: he left larger traces among the Egyptian monuments. In this his reign marks the gradual Egyptianisation of the Ptolemies.

Ptolemy III continued his predecessor's sponsorship of scholarship and literature. The Great Library in the Musaeum was supplemented by a second library built in the Serapeum. He was said to have had every book unloaded in the Alexandria docks seized and copied, returning the copies to their owners and keeping the originals for the Library.[25] It is said that he borrowed the official manuscripts of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides from Athens and forfeited the considerable deposit he paid for them in order to keep them for the Library rather than returning them. The most distinguished scholar at Ptolemy III's court was the polymath and geographer Eratosthenes, most noted for his remarkably accurate calculation of the circumference of the world. Other prominent scholars include the mathematicians Conon of Samos and Apollonius of Perge.[24]

Ptolemy III financed construction projects at temples across Egypt. The most significant of these was the Temple of Horus at Edfu, one of the masterpieces of ancient Egyptian temple architecture and now the best-preserved of all Egyptian temples. Ptolemy III initiated construction on it on 23 August 237 BC. Work continued for most of the Ptolemaic dynasty; the main temple was finished in the reign of his son, Ptolemy IV, in 212 BC, and the full complex was only completed in 142 BC, during the reign of Ptolemy VIII, while the reliefs on the great pylon were finished in the reign of Ptolemy XII.

Decline

editPtolemy IV

editIn 221 BC, Ptolemy III died and was succeeded by his son Ptolemy IV Philopator, a weak king whose rule precipitated the decline of the Ptolemaic Kingdom. His reign was inaugurated by the murder of his mother, and he was always under the influence of royal favourites, who controlled the government. Nevertheless, his ministers were able to make serious preparations to meet the attacks of Antiochus III the Great on Coele-Syria, and the great Egyptian victory of Raphia in 217 BC secured the kingdom. A sign of the domestic weakness of his reign was the rebellions by native Egyptians that took away over half the country for over 20 years. Philopator was devoted to orgiastic religions and to literature. He married his sister Arsinoë, but was ruled by his mistress Agathoclea.

Like his predecessors, Ptolemy IV presented himself as a typical Egyptian Pharaoh and actively supported the Egyptian priestly elite through donations and temple construction. Ptolemy III had introduced an important innovation in 238 BC by holding a synod of all the priests of Egypt at Canopus. Ptolemy IV continued this tradition by holding his own synod at Memphis in 217 BC, after the victory celebrations of the Fourth Syrian War. The result of this synod was the Raphia Decree, issued on 15 November 217 BC and preserved in three copies. Like other Ptolemaic decrees, the decree was inscribed in hieroglyphs, Demotic, and Koine Greek. The decree records the military success of Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III and their benefactions to the Egyptian priestly elite. Throughout, Ptolemy IV is presented as taking on the role of Horus who avenges his father by defeating the forces of disorder led by the god Set. In return, the priests undertook to erect a statue group in each of their temples, depicting the god of the temple presenting a sword of victory to Ptolemy IV and Arsinoe III. A five-day festival was inaugurated in honour of the Theoi Philopatores and their victory. The decree thus seems to represent a successful marriage of Egyptian Pharaonic ideology and religion with the Hellenistic Greek ideology of the victorious king and his ruler cult.[26]

Great Theban Revolt

editMisrule by the Pharaoh in Alexandria led to a nearly successful revolt, led by a priest named Hugronaphor. He proclaimed himself Pharaoh in 205 BC, and ruled upper Egypt until his death in 199 BC. He was succeeded by his son Ankhmakis, whose forces nearly drove the Ptolemies out of the country. The revolutionary dynasty was finally defeated in 186, and a stele celebrating this event was historically significant as the famous Rosetta Stone.[27]

Ptolemy V Epiphanes and Ptolemy VI Philometor

editPtolemy V Epiphanes, son of Philopator and Arsinoë, was a child when he came to the throne, and a series of regents ran the kingdom. Antiochus III the Great of The Seleucid Empire and Philip V of Macedon made a compact to seize the Ptolemaic possessions. Philip seized several islands and places in Caria and Thrace, while the battle of Panium in 200 BC transferred Coele-Syria from Ptolemaic to Seleucid control. After this defeat Egypt formed an alliance with the rising power in the Mediterranean, Rome. Once he reached adulthood Epiphanes became a tyrant, before his early death in 180 BC. He was succeeded by his infant son Ptolemy VI Philometor.

In 170 BC, Antiochus IV Epiphanes invaded Egypt and captured Philometor, installing him at Memphis as a puppet king. Philometor's younger brother (later Ptolemy VIII Physcon) was installed as king by the Ptolemaic court in Alexandria. When Antiochus withdrew, the brothers agreed to reign jointly with their sister Cleopatra II. They soon fell out, however, and quarrels between the two brothers allowed Rome to interfere and to steadily increase its influence in Egypt. Philometor eventually regained the throne. In 145 BC, he was killed in the Battle of Antioch.

Throughout the 160s and 150s BC, Ptolemy VI has also reasserted Ptolemaic control over the northern part of Nubia. This achievement is heavily advertised at the Temple of Isis at Philae, which was granted the tax revenues of the Dodecaschoenus region in 157 BC. Decorations on the first pylon of the Temple of Isis at Philae emphasise the Ptolemaic claim to rule the whole of Nubia. The aforementioned inscription regarding the priests of Mandulis shows that some Nubian leaders at least were paying tribute to the Ptolemaic treasury in this period. In order to secure the region, the strategos of Upper Egypt, Boethus, founded two new cities, named Philometris and Cleopatra in honour of the royal couple.[29][30]

Later Ptolemies

editAfter Ptolemy VI's death a series of civil wars and feuds between the members of the Ptolemaic dynasty started and lasted for over a century. Philometor was succeeded by yet another infant, his son Ptolemy VII Neos Philopator. But Physcon soon returned, killed his young nephew, seized the throne and as Ptolemy VIII soon proved himself a cruel tyrant. On his death in 116 BC he left the kingdom to his wife Cleopatra III and her son Ptolemy IX Philometor Soter II. The young king was driven out by his mother in 107 BC, who reigned jointly with Euergetes's youngest son Ptolemy X Alexander I. In 88 BC Ptolemy IX again returned to the throne, and retained it until his death in 80 BC. He was succeeded by Ptolemy XI Alexander II, the son of Ptolemy X. He was lynched by the Alexandrian mob after murdering his stepmother, who was also his cousin, aunt and wife. These sordid dynastic quarrels left Egypt so weakened that the country became a de facto protectorate of Rome, which had by now absorbed most of the Greek world.

Ptolemy XI was succeeded by a son of Ptolemy IX, Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos, nicknamed Auletes, the flute-player. By now Rome was the arbiter of Egyptian affairs, and annexed both Libya and Cyprus. In 58 BC Auletes was driven out by the Alexandrian mob, but the Romans restored him to power three years later. He died in 51 BC, leaving the kingdom to his ten-year-old son and seventeen-year-old daughter, Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator and Cleopatra VII, who reigned jointly as husband and wife.

Final years

editCleopatra VII

editCleopatra VII ascended the Egyptian throne on 22 March 51 BC upon the death of her father, Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysos.[33] She reigned as queen "philopator" and pharaoh with various male co-regents from 51 to 30 BC.[34]

The demise of the Ptolemies' power coincided with the growing dominance of the Roman Republic. With one empire after another falling to Macedon and the Seleucid empire, the Ptolemies had had little choice but to ally with the Romans, a pact that lasted over 150 years. By Ptolemy XII's time, Rome had achieved a massive amount of influence over Egyptian politics and finances to the point that he declared the Roman senate the guardian of the Ptolemaic Dynasty. He had paid vast sums of Egyptian wealth and resources in tribute to the Romans in order to regain and secure his throne following the rebellion and brief coup led by his older daughters, Tryphaena and Berenice IV. Both daughters were killed in Auletes' reclaiming of his throne; Tryphaena by assassination and Berenice by execution, leaving Cleopatra VII as the oldest surviving child of Ptolemy Auletes. Traditionally, Ptolemaic royal siblings were married to one another on ascension to the throne. These marriages sometimes produced children, and other times were only a ceremonial union to consolidate political power. Ptolemy Auletes expressed his wish for Cleopatra and her brother Ptolemy XIII to marry and rule jointly in his will, in which the Roman senate was named as executor, giving Rome further control over the Ptolemies and, thereby, the fate of Egypt as a nation.

After the death of their father, Cleopatra VII and her younger brother Ptolemy XIII inherited the throne and were married. Their marriage was only nominal, however, and their relationship soon degenerated. Cleopatra was stripped of authority and title by Ptolemy XIII's advisors, who held considerable influence over the young king. Fleeing into exile, Cleopatra attempted to raise an army to reclaim the throne.

Julius Caesar left Rome for Alexandria in 48 BC in order to quell the looming civil war, as war in Egypt, which was one of Rome's greatest suppliers of grain and other expensive goods, would have had a detrimental effect on trade with Rome, especially on Rome's working-class citizens. During his stay in the Alexandrian palace, he received 22-year-old Cleopatra, allegedly carried to him in secret wrapped in a carpet. Caesar agreed to support Cleopatra's claim to the throne. Ptolemy XIII and his advisors fled the palace, turning the Egyptian forces loyal to the throne against Caesar and Cleopatra, who barricaded themselves in the palace complex until Roman reinforcements could arrive to combat the rebellion, known afterward as the Siege of Alexandria. Ptolemy XIII's forces were ultimately defeated at the Battle of the Nile and the king was killed in the conflict, reportedly drowning in the Nile while attempting to flee with his remaining army.

In the summer of 47 BC, having married her younger brother Ptolemy XIV, Cleopatra embarked with Caesar for a two-month trip along the Nile. Together, they visited Dendara, where Cleopatra was being worshiped as pharaoh, an honor beyond Caesar's reach. They became lovers and had a son, Caesarion. In 45 BC, Cleopatra and Caesarion left Alexandria for Rome, where they stayed in a palace built by Caesar in their honor.

In 44 BC, Caesar was murdered in Rome by several Senators. With his death, Rome split between supporters of Mark Antony and Octavian. When Mark Antony seemed to prevail, Cleopatra supported him and, shortly after, they too became lovers and eventually married in Egypt (though their marriage was never recognized by Roman law, as Antony was married to a Roman woman). Their union produced three children; the twins Cleopatra Selene and Alexander Helios, and another son, Ptolemy Philadelphos.

Mark Antony's alliance with Cleopatra angered Rome even more. Branded a power-hungry enchantress by the Romans, she was accused of seducing Antony to further her conquest of Rome. Further outrage followed at the donations of Alexandria ceremony in autumn of 34 BC in which Tarsus, Cyrene, Crete, Cyprus, and Judaea were all to be given as client monarchies to Antony's children by Cleopatra. In his will Antony expressed his desire to be buried in Alexandria, rather than taken to Rome in the event of his death, which Octavian used against Antony, sowing further dissent in the Roman populace.

Right: bust of Cleopatra VII, dated 40–30 BC, Vatican Museums, showing her with a 'melon' hairstyle and Hellenistic royal diadem worn over her head

Octavian was quick to declare war on Antony and Cleopatra while public opinion of Antony was low. Their naval forces met at Actium, where the forces of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa defeated the navy of Cleopatra and Antony. Octavian waited for a year before he claimed Egypt as a Roman province. He arrived in Alexandria and easily defeated Mark Antony's remaining forces outside the city. Facing certain death at the hands of Octavian, Antony attempted suicide by falling on his own sword, but survived briefly. He was taken by his remaining soldiers to Cleopatra, who had barricaded herself in her mausoleum, where he died soon after.

Knowing that she would be taken to Rome to be paraded in Octavian's triumph (and likely executed thereafter), Cleopatra and her handmaidens committed suicide on 12 August 30 BC. Legend and numerous ancient sources claim that she died by way of the venomous bite of an asp, though others state that she used poison, or that Octavian ordered her death himself.

Caesarion, her son by Julius Caesar, nominally succeeded Cleopatra until his capture and supposed execution in the weeks after his mother's death. Cleopatra's children by Antony were spared by Octavian and given to his sister (and Antony's Roman wife) Octavia Minor, to be raised in her household. No further mention is made of Cleopatra and Antony's sons in the known historical texts of that time, but their daughter Cleopatra Selene was eventually married through arrangement by Octavian into the Mauretanian royal line, one of Rome's many client monarchies. Through Cleopatra Selene's offspring the Ptolemaic line intermarried back into the Roman nobility for centuries.

With the deaths of Cleopatra and Caesarion, the dynasty of Ptolemies and the entirety of pharaonic Egypt came to an end. Alexandria remained the capital of the country, but Egypt itself became a Roman province. Octavian became the sole ruler of Rome and began converting it into a monarchy, the Roman Empire.

Roman rule

editUnder Roman rule, Egypt was governed by a prefect selected by the emperor from the Equestrian class and not a governor from the Senatorial order, to prevent interference by the Roman Senate. The main Roman interest in Egypt was always the reliable delivery of grain to the city of Rome. To this end the Roman administration made no change to the Ptolemaic system of government, although Romans replaced Greeks in the highest offices. But Greeks continued to staff most of the administrative offices and Greek remained the language of government except at the highest levels. Unlike the Greeks, the Romans did not settle in Egypt in large numbers. Culture, education and civic life largely remained Greek throughout the Roman period. The Romans, like the Ptolemies, respected and protected Egyptian religion and customs, although the cult of the Roman state and of the Emperor was gradually introduced.[citation needed]

Culture

editPtolemy I, perhaps with advice from Demetrius of Phalerum, founded the Library of Alexandria,[35] a research centre located in the royal sector of the city. Its scholars were housed in the same sector and funded by Ptolemaic rulers.[35] The chief librarian served also as the crown prince's tutor.[36] For the first hundred and fifty years of its existence, the library drew the top Greek scholars from all over the Hellenistic world.[36] It was a key academic, literary and scientific centre in antiquity.[37]

Greek culture had a long but minor presence in Egypt long before Alexander the Great founded the city of Alexandria. It began when Greek colonists, encouraged by many Pharaohs, set up the trading post of Naucratis. As Egypt came under foreign domination and decline, the Pharaohs depended on the Greeks as mercenaries and even advisors. When the Persians took over Egypt, Naucratis remained an important Greek port and the colonist population were used as mercenaries by both the rebel Egyptian princes and the Persian kings, who later gave them land grants, spreading Greek culture into the valley of the Nile. When Alexander the Great arrived, he established Alexandria on the site of the Persian fort of Rhakortis. Following Alexander's death, control passed into the hands of the Lagid (Ptolemaic) Dynasty; they built Greek cities across their empire and gave land grants across Egypt to the veterans of their many military conflicts. Hellenistic civilization continued to thrive even after Rome annexed Egypt after the battle of Actium and did not decline until the Islamic conquests.

Art

editPtolemaic art was produced during the reign of the Ptolemaic Rulers (304–30 BC), and was concentrated primarily within the bounds of the Ptolemaic Empire.[39][40] At first, artworks existed separately in either the Egyptian or the Hellenistic style, but over time, these characteristics began to combine. The continuation of the Egyptian art style evidences the Ptolemies' commitment to maintaining Egyptian customs. This strategy not only helped to legitimize their rule, but also placated the general population.[41] Greek-style art was also created during this time and existed in parallel to the more traditional Egyptian art, which could not be altered significantly without changing its intrinsic, primarily-religious function.[42] Art found outside of Egypt itself, though within the Ptolemaic Kingdom, sometimes used Egyptian iconography as it had been used previously, and sometimes adapted it.[43][44]

For example, the faience sistrum inscribed with the name of Ptolemy has some deceptively Greek characteristics, such as the scrolls at the top. However, there are many examples of nearly identical sistrums and columns dating all the way to Dynasty 18 in the New Kingdom. It is, therefore, purely Egyptian in style. Aside from the name of the king, there are other features that specifically date this to the Ptolemaic period. Most distinctively is the color of the faience. Apple green, deep blue, and lavender-blue are the three colors most frequently used during this period, a shift from the characteristic blue of the earlier kingdoms.[38] This sistrum appears to be an intermediate hue, which fits with its date at the beginning of the Ptolemaic empire.

During the reign of Ptolemy II, Arsinoe II was deified either as stand-alone goddesses or as a personification of another divine figure and given their own sanctuaries and festivals in association to both Egyptian and Hellenistic gods (such as Isis of Egypt and Hera of Greece).[45] For example, Head Attributed to Arsinoe II deified her as an Egyptian goddess. However, the Marble head of a Ptolemaic queen deified Arsinoe II as Hera.[45] Coins from this period also show Arsinoe II with a diadem that is solely worn by goddesses and deified royal women.[46]

The Statuette of Arsinoe II was created c. 150–100 BC, well after her death, as a part of her own specific posthumous cult which was started by her husband Ptolemy II. The figure also exemplifies the fusing of Greek and Egyptian art. Although the backpillar and the goddess's striding pose is distinctively Egyptian, the cornucopia she holds and her hairstyle are both Greek in style. The rounded eyes, prominent lips, and overall youthful features show Greek influence as well.[48]

Despite the unification of Greek and Egyptian elements in the intermediate Ptolemaic period, the Ptolemaic Kingdom also featured prominent temple construction as a continuation of developments based on Egyptian art tradition from the Thirtieth Dynasty.[49][50] Such behavior expanded the rulers' social and political capital and demonstrated their loyalty toward Egyptian deities, to the satisfaction of the local people.[51] Temples remained very New Kingdom and Late Period Egyptian in style though resources were oftentimes provided by foreign powers.[49] Temples were models of the cosmic world with basic plans retaining the pylon, open court, hypostyle halls, and dark and centrally located sanctuary.[49] However, ways of presenting text on columns and reliefs became formal and rigid during the Ptolemaic Dynasty. Scenes were often framed with textual inscriptions, with a higher text to image ratio than seen previously during the New Kingdom.[49] For example, a relief in the temple of Kom Ombo is separated from other scenes by two vertical columns of texts. The figures in the scenes are smooth, rounded, and high relief, a style continued throughout the 30th Dynasty. The relief represents the interaction between the Ptolemaic kings and the Egyptian deities, which legitimized their rule in Egypt .[47]

In Ptolemaic art, the idealism seen in the art of previous dynasties continues, with some alterations. Women are portrayed as more youthful, and men begin to be portrayed in a range from idealistic to realistic.[44][45] An example of realistic portrayal is the Berlin Green Head, which shows the non-idealistic facial features with vertical lines above the bridge of the nose, lines at the corners of the eyes and between the nose and the mouth.[52] The influence of Greek art was shown in an emphasis on the face that was not previously present in Egyptian art and incorporation of Greek elements into an Egyptian setting: individualistic hairstyles, the oval face, "round [and] deeply set" eyes, and the small, tucked mouth closer to the nose.[53] Early portraits of the Ptolemies featured large and radiant eyes in association to the rulers' divinity as well as general notions of abundance.[54]

Religion

editWhen Ptolemy I Soter made himself king of Egypt, he created a new god, Serapis, to garner support from both Greeks and Egyptians. Serapis was the patron god of Ptolemaic Egypt, combining the Egyptian gods Apis and Osiris with the Greek deities Zeus, Hades, Asklepios, Dionysos, and Helios; he had powers over fertility, the sun, funerary rites, and medicine. His growth and popularity reflected a deliberate policy by the Ptolemaic state, and was characteristic of the dynasty's use of Egyptian religion to legitimize their rule and strengthen their control.

The cult of Serapis included the worship of the new Ptolemaic line of pharaohs; the newly established Hellenistic capital of Alexandria supplanted Memphis as the preeminent religious city. Ptolemy I also promoted the cult of the deified Alexander, who became the state god of the Ptolemaic kingdom. Many rulers also promoted individual cults of personality, including celebrations at Egyptian temples.

Because the monarchy remained staunchly Hellenistic, despite otherwise co-opting Egyptian faith traditions, religion during this period was highly syncretic. The wife of Ptolemy II, Arsinoe II, was often depicted in the form of the Greek goddess Aphrodite, but she wore the crown of lower Egypt, with ram's horns, ostrich feathers, and other traditional Egyptian indicators of royalty and/or deification; she wore the vulture headdress only on the religious portion of a relief. Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemaic line, was often depicted with characteristics of the goddess Isis; she usually had either a small throne as her headdress or the more traditional sun disk between two horns.[55] Reflecting Greek preferences, the traditional table for offerings disappeared from reliefs during the Ptolemaic period, while male gods were no longer portrayed with tails, so as to make them more human-like in accordance with the Hellenistic tradition.

Nevertheless, the Ptolemies remained generally supportive of the Egyptian religion, which always remained key to their legitimacy. Egyptian priests and other religious authorities enjoyed royal patronage and support, more or less retaining their historical privileged status. Temples remained the focal point of social, economic, and cultural life; the first three reigns of the dynasty were characterized by rigorous temple building, including the completion of projects left over from the previous dynasty; many older or neglected structures were restored or enhanced.[56] The Ptolemies generally adhered to traditional architectural styles and motifs. In many respects, the Egyptian religion thrived: temples became centers of learning and literature in the traditional Egyptian style.[56] The worship of Isis and Horus became more popular, as did the practice of offering animal mummies.

Memphis, while no longer the center of power, became the second city after Alexandria, and enjoyed considerable influence; its High Priests of Ptah, an ancient Egyptian creator god, held considerable sway among the priesthood and even with the Ptolemaic kings. Saqqara, the city's necropolis, was a leading center of worship of Apis bull, which had become integrated into the national mythos. The Ptolemies also lavished attention on Hermopolis, the cult center of Thoth, building a Hellenistic-style temple in his honor. Thebes continued to be a major religious center and home to a powerful priesthood; it also enjoyed royal development, namely of the Karnak complex devoted to the Osiris and Khonsu. The city's temples and communities prosperous, while a new Ptolemaic style of cemeteries were built.[56]

A common stele that appears during the Ptolemaic Dynasty is the cippus, a type of religious object produced for the purpose of protecting individuals. These magical stelae were made of various materials such as limestone, chlorite schist, and metagreywacke, and were connected with matters of health and safety. Horus on the Crocodiles cippi during the Ptolemaic Period generally featured the child form of the Egyptian god Horus, Horpakhered (or Harpocrates). This portrayal refers to the myth of Horus triumphing over dangerous animals in the marshes of Khemmis with magic power (also known as Akhmim).[57][58]

Society

editPtolemaic Egypt was highly stratified in terms of both class and language. More than any previous foreign rulers, the Ptolemies retained or co-opted many aspects of the Egyptian social order, using Egyptian religion, traditions, and political structures to increase their own power and wealth.

As before, peasant farmers remained the vast majority of the population, while agricultural land and produce were owned directly by the state, temple, or noble family that owned the land. Macedonians and other Greeks now formed the new upper classes, replacing the old native aristocracy. A complex state bureaucracy was established to manage and extract Egypt's vast wealth for the benefit of the Ptolemies and the landed gentry.

Greeks held virtually all the political and economic power, while native Egyptians generally occupied only the lower posts; over time, Egyptians who spoke Greek were able to advance further and many individuals identified as "Greek" were of Egyptian descent. Eventually, a bilingual and bicultural social class emerged in Ptolemaic Egypt.[59] Priests and other religious officials remained overwhelmingly Egyptian, and continued to enjoy royal patronage and social prestige, as the Ptolemies' relied on the Egyptian faith to legitimize their rule and placate the populace.

Although Egypt was a prosperous kingdom, with the Ptolemies lavishing patronage through religious monuments and public works, the native population enjoyed few benefits; wealth and power remained overwhelmingly in the hands of Greeks. Subsequently, uprising and social unrest were frequent, especially by the early third century BC. Egyptian nationalism reached a peak in the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator (221–205 BC), when a succession of native self-proclaimed "pharaoh" gained control over one district. This was only curtailed nineteen years later when Ptolemy V Epiphanes (205–181 BC) succeeded in subduing them, though underlying grievances were never extinguished, and riots erupted again later in the dynasty.

Coinage

editPtolemaic Egypt produced extensive series of coinage in gold, silver and bronze. These included issues of large coins in all three metals, most notably gold pentadrachm and octadrachm, and silver tetradrachm, decadrachm and pentakaidecadrachm.[citation needed]

Military

editThe military of Ptolemaic Egypt is considered to have been one of the best of the Hellenistic period, benefiting from the kingdom's vast resources and its ability to adapt to changing circumstances.[60] The Ptolemaic military initially served a defensive purpose, primarily against competing diadochi claimants and rival Hellenistic states like the Seleucid Empire. By the reign of Ptolemy III (246 to 222 BC), its role was more imperialistic, helping extend Ptolemaic control or influence over Cyrenaica, Coele-Syria, and Cyprus, as well as over cities in Anatolia, southern Thrace, the Aegean islands, and Crete. The military expanded and secured these territories while continuing its primary function of protecting Egypt; its main garrisons were in Alexandria, Pelusium in the Delta, and Elephantine in Upper Egypt. The Ptolemies also relied on the military to assert and maintain their control over Egypt, often by virtue of their presence. Soldiers served in several units of the royal guard and were mobilized against uprisings and dynastic usurpers, both of which became increasingly common. Members of the army, such as the machimoi (low ranking native soldiers) were sometimes recruited as guards for officials, or even to help enforce tax collection.[61]

Army

editThe Ptolemies maintained a standing army throughout their reign, made up of both professional soldiers (including mercenaries) and recruits. From the very beginning the Ptolemaic army demonstrated considerable resourcefulness and adaptability. In his fight for control over Egypt, Ptolemy I had relied on a combination of imported Greek troops, mercenaries, native Egyptians, and even prisoners of war.[60] The army was characterized by its diversity and maintained records of its troops' national origins, or patris.[62] In addition to Egypt itself, soldiers were recruited from Macedonia, Cyrenaica (modern Libya), mainland Greece, the Aegean, Asia Minor, and Thrace; overseas territories were often garrisoned with local soldiers.[63]

By the second and first centuries BC, increasing warfare and expansion, coupled with reduced Greek immigration, led to increasing reliance on native Egyptians; however, Greeks retained the higher ranks of royal guards, officers, and generals.[60] Though present in the military from its founding, native troops were sometimes looked down upon and distrusted due to their reputation for disloyalty and tendency to aid local revolts;[64] however, they were well regarded as fighters, and beginning with the reforms of Ptolemy V in the early third century BC, they appeared more frequently as officers and cavalrymen.[65] Egyptian soldiers also enjoyed a socioeconomic status higher than the average native.[66]

To obtain reliable and loyal soldiers, the Ptolemies developed several strategies that leveraged their ample financial resources and even Egypt's historical reputation for wealth; royal propaganda could be evidenced in a line by the poet Theocritus, "Ptolemy is the best paymaster a free man could have".[60] Mercenaries were paid a salary (misthos) of cash and grain rations; an infantryman in the third century BC earned about one silver drachma daily. This attracted recruits from across the eastern Mediterranean, who were sometimes referred to misthophoroi xenoi — literally "foreigners paid with a salary". By the second and first century BC, misthophoroi were mainly recruited within Egypt, notably among the Egyptian population. Soldiers were also given land grants called kleroi, whose size varied according to the military rank and unit, as well as stathmoi, or residences, which were sometimes in the home of local inhabitants; men who settled in Egypt through these grants were known as cleruchs. At least from about 230 BC, these land grants were provided to machimoi, lower ranking infantry usually of Egyptian origin, who received smaller lots comparable to traditional land allotments in Egypt.[60] Kleroi grants could be extensive: a cavalryman could receive at least 70 arouras of land, equal to about 178,920 square metres, and as much as 100 arouras; infantrymen could expect 30 or 25 arouras and machimoi at least five auroras, considered enough for one family.[67] The lucrative nature of military service under the Ptolemies appeared to have been effective at ensuring loyalty. Few mutinies and revolts are recorded, and even rebellious troops would be placated with land grants and other incentives.[68]

As in other Hellenistic states, the Ptolemaic army inherited the doctrines and organization of Macedonia, albeit with some variations over time.[69] The core of the army consisted of cavalry and infantry; as under Alexander, cavalry played a larger role both numerically and tactically, while the Macedonian phalanx served as the primary infantry formation. The multiethnic nature of the Ptolemaic army was an official organizational principle: soldiers were evidently trained and utilized based on their national origin; Cretans generally served as archers, Libyans as heavy infantry, and Thracians as cavalry.[60] Similarly, units were grouped and equipped based on ethnicity. Nevertheless, different nationalities were trained to fight together, and most officers were of Greek or Macedonian origin, which allowed for a degree of cohesion and coordination. Military leadership and the figure of the king and queen were central for ensuring unity and morale among multiethnic troops; at the battle of Raphia, the presence of Ptolemy was reportedly critical in maintaining and boosting the fighting spirit of both Greek and Egyptian soldiers.[60]

Navy

editThe Ptolemaic Kingdom was considered a major naval power in the eastern Mediterranean.[70] Some modern historians characterize Egypt during this period as a thalassocracy, owing to its innovation of "traditional styles of Mediterranean sea power", which allowed its rulers to "exert power and influence in unprecedented ways".[71] With territories and vassals spread across the eastern Mediterranean, including Cyprus, Crete, the Aegean islands, and Thrace, the Ptolemies required a large navy to defend against enemies like the Seleucids and Macedonians.[72] The Ptolemaic navy also protected the kingdom's lucrative maritime trade and engaged in antipiracy measures, including along the Nile.[73]

Like the army, the origins and traditions of the Ptolemaic navy were rooted in the wars following the death of Alexander in 320 BC. Various diadochi competed for naval supremacy over the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean,[74] and Ptolemy I founded the navy to help defend Egypt and consolidate his control against invading rivals.[75] He and his immediate successors turned to developing the navy to project power overseas, rather than build a land empire in Greece or Asia.[76] Notwithstanding an early crushing defeat at the Battle of Salamis in 306 BC, the Ptolemaic navy became the dominant maritime force in the Aegean and eastern Mediterranean for the next several decades. Ptolemy II maintained his father's policy of making Egypt the preeminent naval power in the region; during his reign (283 to 246 BC), the Ptolemaic navy became the largest in the Hellenistic world and had some of the largest warships ever built in antiquity.[77] The navy reached its height following the victory of Ptolemy II during the First Syrian War (274–271 BC), succeeding in repelling both Seleucid and Macedonian control of the eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean.[78] During the subsequent Chremonidean War, the Ptolemaic navy succeeded in blockading Macedonia and containing its imperial ambitions to mainland Greece.[79]

Beginning with the Second Syrian War (260–253 BC), the navy suffered a series of defeats and declined in military importance, which coincided with the loss of Egypt's overseas possessions and the erosion of its maritime hegemony. The navy was relegated primarily to a protective and antipiracy role for the next two centuries, until its partial revival under Cleopatra VII, who sought to restore Ptolemaic naval supremacy amid the rise of Rome as a major Mediterranean power.[80] Egyptian naval forces took part in the decisive battle of Actium during the final war of the Roman Republic, but once again suffered a defeat that culminated with the end of Ptolemaic rule.

At its apex under Ptolemy II, the Ptolemaic navy may have had as many as 336 warships,[81] with Ptolemy II reportedly having at his disposal more than 4,000 ships (including transports and allied vessels).[81] Maintaining a fleet of this size would have been costly, and reflected the vast wealth and resources of the kingdom.[81] The main naval bases were at Alexandria and Nea Paphos in Cyprus. The navy operated throughout the eastern Mediterranean, Aegean Sea, and Levantine Sea, and along the Nile, patrolling as far as the Red Sea towards the Indian Ocean.[82] Accordingly, naval forces were divided into four fleets: the Alexandrian,[83] Aegean,[84] Red Sea,[85] and Nile River.[86]

Cities

editWhile ruling Egypt, the Ptolemaic Dynasty built many Greek settlements throughout their Empire, to either Hellenize new conquered peoples or reinforce the area. Egypt had only three main Greek cities—Alexandria, Naucratis, and Ptolemais.

Naucratis

editOf the three Greek cities, Naucratis, although its commercial importance was reduced with the founding of Alexandria, continued in a quiet way its life as a Greek city-state. During the interval between the death of Alexander and Ptolemy's assumption of the style of king, it even issued an autonomous coinage. And the number of Greek men of letters during the Ptolemaic and Roman period, who were citizens of Naucratis, proves that in the sphere of Hellenic culture Naucratis held to its traditions. Ptolemy II bestowed his care upon Naucratis. He built a large structure of limestone, about 100 metres (330 ft) long and 18 metres (59 ft) wide, to fill up the broken entrance to the great Temenos; he strengthened the great block of chambers in the Temenos, and re-established them. At the time when Sir Flinders Petrie wrote the words just quoted[citation needed] the great Temenos was identified with the Hellenion. But Mr. Edgar has recently pointed out that the building connected with it was an Egyptian temple, not a Greek building.[citation needed] Naucratis, therefore, in spite of its general Hellenic character, had an Egyptian element. That the city flourished in Ptolemaic times "we may see by the quantity of imported amphorae, of which the handles stamped at Rhodes and elsewhere are found so abundantly." The Zeno papyri show that it was the chief port of call on the inland voyage from Memphis to Alexandria, as well as a stopping-place on the land-route from Pelusium to the capital. It was attached, in the administrative system, to the Saïte nome.

Alexandria

editA major Mediterranean port of Egypt, in ancient times and still today, Alexandria was founded in 331 BC by Alexander the Great. According to Plutarch, the Alexandrians believed that Alexander the Great's motivation to build the city was his wish to "found a large and populous Greek city that should bear his name." Located 30 kilometres (19 mi) west of the Nile's westernmost mouth, the city was immune to the silt deposits that persistently choked harbors along the river. Alexandria became the capital of the Hellenized Egypt of King Ptolemy I (reigned 323–283 BC). Under the wealthy Ptolemaic Dynasty, the city soon surpassed Athens as the cultural center of the Hellenic world.

Laid out on a grid pattern, Alexandria occupied a stretch of land between the sea to the north and Lake Mareotis to the south; a man-made causeway, over three-quarters of a mile long, extended north to the sheltering island of Pharos, thus forming a double harbor, east and west. On the east was the main harbor, called the Great Harbor; it faced the city's chief buildings, including the royal palace and the famous Library and Museum. At the Great Harbor's mouth, on an outcropping of Pharos, stood the lighthouse, built c. 280 BC. Now vanished, the lighthouse was reckoned as one of the Seven Wonders of the World for its unsurpassed height (perhaps 140 metres or 460 ft); it was a square, fenestrated tower, topped with a metal fire basket and a statue of Zeus the Savior.

The Library, at that time the largest in the world, contained several hundred thousand volumes and housed and employed scholars and poets. A similar scholarly complex was the Museum (Mouseion, "hall of the Muses"). During Alexandria's brief literary golden period, c. 280–240 BC, the Library subsidized three poets—Callimachus, Apollonius of Rhodes, and Theocritus—whose work now represents the best of Hellenistic literature. Among other thinkers associated with the Library or other Alexandrian patronage were the mathematician Euclid (c. 300 BC), the inventor Archimedes (287 BC – c. 212 BC), and the polymath Eratosthenes (c. 225 BC).[87]

Cosmopolitan and flourishing, Alexandria possessed a varied population of Greeks, Egyptians and other Oriental peoples, including a sizable minority of Jews, who had their own city quarter. Periodic conflicts occurred between Jews and ethnic Greeks. According to Strabo, Alexandria had been inhabited during Polybius' lifetime by local Egyptians, foreign mercenaries and the tribe of the Alexandrians, whose origin and customs Polybius identified as Greek.

The city enjoyed a calm political history under the Ptolemies. It passed, with the rest of Egypt, into Roman hands in 30 BC, and became the second city of the Roman Empire.

Ptolemais

editThe second Greek city founded after the conquest of Egypt was Ptolemais, 400 miles (640 km) up the Nile, where there was a native village called Psoï, in the nome called after the ancient Egyptian city of Thinis. If Alexandria perpetuated the name and cult of the great Alexander, Ptolemais was to perpetuate the name and cult of the founder of the Ptolemaic time. Framed in by the barren hills of the Nile Valley and the Egyptian sky, here a Greek city arose, with its public buildings and temples and theatre, no doubt exhibiting the regular architectural forms associated with Greek culture, with a citizen-body Greek in blood, and the institutions of a Greek city. If there is some doubt whether Alexandria possessed a council and assembly, there is none in regard to Ptolemais. It was more possible for the kings to allow a measure of self-government to a people removed at that distance from the ordinary residence of the court. We have still, inscribed on stone, decrees passed in the assembly of the people of Ptolemais, couched in the regular forms of Greek political tradition: It seemed good to the boule and to the demos: Hermas son of Doreon, of the deme Megisteus, was the proposer: Whereas the prytaneis who were colleagues with Dionysius the son of Musaeus in the 8th year, etc.

Demographics

editThe Ptolemaic Kingdom was diverse and cosmopolitan. Beginning under Ptolemy I Soter, Macedonians and other Greeks were given land grants and allowed to settle with their families, encouraging tens of thousands of Greek mercenaries and soldiers to immigrate where they became a landed class of royal soldiers.[88] Greeks soon became the dominant elite; native Egyptians, though always the majority, generally occupied lower posts in the Ptolemaic government. Over time, the Greeks in Egypt became somewhat homogenized and the cultural distinctions between immigrants from different regions of Greece became blurred.[89]

Many Jews were imported from neighboring Judea by the thousands for being renowned fighters, also establishing an important community. Other foreign groups settled from across the ancient world, usually as cleruchs who had been granted land in exchange for military service.

Of the many foreign groups who had come to settle in Egypt, the Greeks were the most privileged. They were partly spread as allotment-holders over the country, forming social groups, in the country towns and villages, side by side with the native population, partly gathered in the three Greek cities, the old Naucratis, founded before 600 BC (in the interval of Egyptian independence after the expulsion of the Assyrians and before the coming of the Persians), and the two new cities, Alexandria by the sea, and Ptolemais in Upper Egypt. Alexander and his Seleucid successors founded many Greek cities all over their dominions.

Greek culture was so much bound up with the life of the city-state that any king who wanted to present himself to the world as a genuine champion of Hellenism had to do something in this direction, but the king of Egypt, ambitious to shine as a Hellene, would find Greek cities, with their republican tradition and aspirations to independence, inconvenient elements in a country that lent itself, as no other did, to bureaucratic centralization. The Ptolemies therefore limited the number of Greek city-states in Egypt to Alexandria, Ptolemais, and Naucratis.

Outside of Egypt, the Ptolemies exercised control over Greek cities in Cyrenaica, Cyprus, and on the coasts and islands of the Aegean, but they were smaller than Greek poleis in Egypt. There were indeed country towns with names such as Ptolemais, Arsinoe, and Berenice, in which Greek communities existed with a certain social life and there were similar groups of Greeks in many of the old Egyptian towns, but they were not communities with the political forms of a city-state. Yet if they had no place of political assembly, they often had their own gymnasium, the essential sign of Hellenism, serving something of the purpose of a university for the young men. Far up the Nile at Ombi a gymnasium of the local Greeks was found in 136–135 BC, which passed resolutions and corresponded with the king. Also, in 123 BC, when there was trouble in Upper Egypt between the towns of Crocodilopolis and Hermonthis, the negotiators sent from Crocodilopolis were the young men attached to the gymnasium, who, according to the Greek tradition, ate bread and salt with the negotiators from the other town. All the Greek dialects of the Greek world gradually became assimilated in the Koine Greek dialect that was the common language of the Hellenistic world. Generally, the Greeks of Ptolemaic Egypt felt like representatives of a higher civilization but were curious about the native culture of Egypt.

Jews

editThe Jews who lived in Egypt had originally immigrated from the Southern Levant. Within a few generations the Jews spoke Greek, the dominant language of Egypt at the time, and not the Hebrew or Aramaic of the first immigrants.[90] According to Jewish legend the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures, was written by seventy-two Jewish translators for Ptolemy II.[91] That is confirmed by historian Flavius Josephus, who writes that Ptolemy, desirous to collect every book in the habitable earth, applied Demetrius Phalereus to the task of organizing an effort with the Jewish high priests to translate the Jewish books of the Law for his library.[92] Josephus thus places the origins of the Septuagint in the 3rd century BC, when Demetrius and Ptolemy II lived. According to one Jewish legend, the seventy wrote their translations independently from memory, and the resultant works were identical at every letter. However, Josephus states they worked together arguing over the translation and finished the work in 72 days. Josephus goes into great detail on the elaborate preparations and regal treatment of the 70 elders of the tribes of Israel chosen to accomplish the task in his Antiquities of the Jews Book 12, chapter 2, which is dedicated to the description of this famous event.[93]

Arabs

editIn 1990, more than 2,000 papyri written by Zeno of Caunus from the time of Ptolemy II Philadelphus were discovered, which contained at least 19 references to Arabs in the area between the Nile and the Red Sea, and mentioned their jobs as police officers in charge of "ten person units", and some others were mentioned as shepherds.[94] Arabs in Ptolemaic Egypt and Syria raided and attacked both sides of the conflict between the Ptolemaic Kingdom and its enemies.[95][96]

Agriculture

editThe early Ptolemies increased cultivatable land through irrigation and land reclamation. The Ptolemies drained the marshes of the Faiyum to create a new province of cultivatable land.[97] They also introduced crops such as durum wheat and intensified the production of goods such as wool. Wine production increased dramatically during the Ptolemaic period, as the new Greek ruling class greatly preferred wine to the beer traditionally produced in Egypt. Vines from regions like Crete were planted in Egypt in an attempt to produce Greek wines.[98]

List of Ptolemaic rulers

editSee also

editNotes

edit- ^ Scholars also argue that the kingdom was founded in 304 BC because of different use of calendars: Ptolemy crowned himself in 304 BC on the ancient Egyptian calendar but in 305 BC on the ancient Macedonian calendar; to resolve the issue, the year 305/4 was counted as the first year of Ptolemaic Kingdom in Demotic papyri.

References

edit- ^ Buraselis, Stefanou and Thompson ed; The Ptolemies, the Sea and the Nile: Studies in Waterborne Power., (Cambridge University Press, 2013), 10.

- ^ R. C. C. Law (1979). "North Africa in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods, 323 BC to AD 305". In J. D. Fage (ed.). The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521215923.005. ISBN 9781139054560.

- ^ a b c Strootman, R. (2009). "The Hellenistic royal court" (PDF). Mnemosyne. 62 (1): 168. doi:10.1163/156852509X340291. hdl:1874/386645. S2CID 154234093.

... the Ptolemies were inaugurated as basileus in Alexandria and as pharaoh in Memphis ...

- ^ a b c Stephens, S. A. (2003). Seeing double: intercultural poetics in Ptolemaic Alexandria. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 37. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520927384.

... their role continue to be dual—basileus to the Greek population; pharaoh to the Egyptian ...

- ^ Steven Snape (16 March 2019). "Estimating Population in Ancient Egypt". Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica, 18.21.9, (original)

- ^ Hölbl, G. (2001). A history of the Ptolemaic empire. Psychology Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780415234894.

- ^ Nardo, Don (13 March 2009). Ancient Greece. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-7377-4624-2.

- ^ a b c d e "Ancient Egypt – Macedonian and Ptolemaic Egypt (332–30 bce)". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- ^ Rutherford, Ian (2016). Greco-Egyptian Interactions: Literature, Translation, and Culture, 500 BCE-300 CE. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965612-7.

- ^ Robins, Gay (2008). The Art of Ancient Egypt (Revised ed.). United States: Harvard University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-674-03065-7.

- ^ Hölbl 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Rawles 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Bagnall, Director of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World Roger S. (2004). Egypt from Alexander to the Early Christians: An Archaeological and Historical Guide. Getty Publications. pp. 11–21. ISBN 978-0-89236-796-2.

- ^ Lewis, Naphtali (1986). Greeks in Ptolemaic Egypt: Case Studies in the Social History of the Hellenistic World. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 5. ISBN 0-19-814867-4.

- ^ Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. "The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acha/hd_acha.htm (October 2004) Source: The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.) | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Hemingway, Colette, and Seán Hemingway. "The Rise of Macedonia and the Conquests of Alexander the Great". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/alex/hd_alex.htm (October 2004) Source: The Rise of Macedonia and the Conquests of Alexander the Great | Thematic Essay | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History | The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- ^ Sewell-Lasater, T. L. (2020). Becoming Kleopatra: Ptolemaic Royal Marriage, Incest, and the Path to Female Rule. University of Houston (Thesis). p. 16. ProQuest 2471466915.

- ^ Goyette, M. (2010). Ptolemy II Philadelphus and the dionysiac model of political authority. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections, 2(1), 1–13. https://egyptianexpedition.org/articles/ptolemy-ii-philadelphus-and-the-dionysiac-model-of-political-authority/

- ^ Wasson, Donald L. "Ptolemaic Dynasty". World History Encyclopedia, 4 April 2021.

- ^ Grabbe 2008, p. 268: In a treaty of 301, this region was assigned to Seleucus; however, Ptolemy had just seized it and refused to return it. Because Ptolemy had been very helpful to Seleucus in the past, the latter did not press his claim, but the Seleucid empire continued to regard the region as rightfully theirs. The result was the series of Syrian Wars in which the Seleucids attempted to take the territory back.

- ^ Ptolemy II Philadelphus [308–246 BC. Mahlon H. Smith. Retrieved 2010-06-13.

- ^ a b c Burstein (2007), p. 7

- ^ a b Hölbl 2000, p. 63-65.

- ^ Galen Commentary on the Epidemics 3.17.1.606

- ^ Hölbl 2000, pp. 162–4.

- ^ Veïsse, Anne-Emmanuelle, 'The ‘Great Theban Revolt’, 206–186 bce', in Paul J. Kosmin, and Ian S. Moyer (eds), Cultures of Resistance in the Hellenistic East (Oxford, 2022; online edn, Oxford Academic, 18 Aug. 2022), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192863478.003.0003, accessed 15 Nov. 2024.

- ^ Fletcher 2008, pp. 246–247, image plates and captions

- ^ Török, László (2009). Between Two Worlds: The Frontier Region Between Ancient Nubia and Egypt, 3700 BC-AD 500. Leiden, New York, Köln: Brill. pp. 400–404. ISBN 978-90-04-17197-8.

- ^ Grainger 2010, p. 325

- ^ Cleopatra: A Life

- ^ Fischer-Bovet, Christelle (22 December 2015), "Cleopatra VII, 69–30 BCE", Oxford Classical Dictionary, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.1672, ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5, retrieved 12 June 2023

- ^ Hölbl 2000, p. 231.

- ^ Hölbl 2000, p. 231, 248.

- ^ a b Peters (1970), p. 193

- ^ a b Peters (1970), p. 194

- ^ Peters (1970), p. 195f

- ^ a b Thomas, Ross. "Ptolemaic and Roman Faience Vessels" (PDF). The British Museum. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Robins, Gay (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 10, 231. ISBN 9780674030657. OCLC 191732570.

- ^ Lloyd, Alan (2003). "The Ptolemaic Period (332-30 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. p. 393. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198150343.003.0013. ISBN 978-0-19-280458-7.

- ^ Manning, J.G. (2010). The Historical Understanding of the Ptolemaic State. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 34–35.

- ^ Malek, Jaromir (1999). Egyptian Art. London: Phaidon Press Limited. p. 384.

- ^ "Bronze statuette of Horus | Egyptian, Ptolemaic | Hellenistic | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Faience amulet of Mut with double crown | Egyptian, Ptolemaic | Hellenistic". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ a b c "Marble head of a Ptolemaic queen | Greek | Hellenistic | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ Pomeroy, Sarah (1990). Women in Hellenistic Egypt: From Alexander to Cleopatra. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 29.

- ^ a b Robins, Gay (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 236. ISBN 9780674030657. OCLC 191732570.

- ^ "Statuette of Arsinoe II for her Posthumous Cult | Ptolemaic Period | The Met". The Metropolitan Museum of Art, i.e. The Met Museum. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d Robins, Gay (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674030657. OCLC 191732570.

- ^ Rosalie, David (1993). Discovering Ancient Egyptology. p. 99.

- ^ Fischer-Bovet, Christelle (2007). "Army and Egyptian Temple Building Under the Ptolemies" (PDF). Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Citation error. See inline comment how to fix. [verification needed]

- ^ Citation error. See inline comment how to fix. [verification needed]

- ^ Török, László (2011). Hellenizing art in ancient Nubia, 300 BC-AD 250, and its Egyptian models : a study in "acculturation". Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004211285. OCLC 744946342.

- ^ "Egyptian Art During the Ptolemaic Period of Egyptian History". Antiquities Experts. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ a b c Hill, Marsha. "Egypt in the Ptolemaic Period." In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ptol/hd_ptol.htm (October 2016)

- ^ Robins, Gay (2008). The art of ancient Egypt (Rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 244. ISBN 9780674030657. OCLC 191732570.

- ^ Seele, Keith C. (1947). "Horus on the Crocodiles". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 6 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1086/370811. JSTOR 542233. S2CID 161676438.

- ^ Bingen, Jean (2007). Hellenistic Egypt: Monarchy, Society, Economy, Culture. University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-520-25141-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fischer-Bovet, Christelle (4 March 2015). "The Ptolemaic Army". Oxford Handbook Topics in Classical Studies. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935390.013.75. ISBN 978-0-19-993539-0. Retrieved 8 June 2020 – via Oxford Handbooks Online.

- ^ Christelle Fischer-Bovet, "Egyptian Warriors: The Machimoi of Herodotus and the Ptolemaic Army," Classical Quarterly 63 (2013): 209–236, 222–223; P.Tebt. I 121, with Andrew Monson, "Late Ptolemaic Capitation Taxes and the Poll Tax in Roman Egypt," Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 51 (2014): 127–160, 134.

- ^ Sean Lesquier, Les institutions militaires de l'Egypte sous les Lagides (Paris: Ernest Leroux, 1911);

- ^ Roger S. Bagnall, "The Origins of Ptolemaic Cleruchs," Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrology 21 (1984): 7–20, 16–18

- ^ Heinz Heinen, Heer und Gesellschaft im Ptolemäerreich, in Vom hellenistischen Osten zum römischen Westen: Ausgewählte Schriften zur Alten Geschichte. Steiner, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-515-08740-0, pp. 61–84

- ^ Crawford, Kerkeosiris, Table IV, 155–159; Edmond Van 't Dack, "Sur l'évolution des institutions militaires lagides," in Armées et fiscalité dans le monde antique. Actes du colloque national, Paris, 14–16 octobre 1976 (Paris: Editions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique, 1977): 87 and note 1.

- ^ Christelle Fischer-Bovet (2013), "Egyptian warriors: the Machimoi of Herodotus and the Ptolemaic Army". The Classical Quarterly 63 (01), p. 225, doi:10.1017/S000983881200064X

- ^ Dorothy J. Crawford, Kerkeosiris: An Egyptian village in the Ptolemaic period (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971) estimated that a family could live on 5 arouras; see P.Tebt. I 56 (Kerkeosiris, late second century BC).

- ^ Michel M. Austin, The Hellenistic World from Alexander to the Roman Conquest: A Selection of Ancient Sources in Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006) #283, l. 20.

- ^ Nick Sekunda, "Military Forces. A. Land Forces," in The Cambridge History of Greek and Roman Warfare (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007)

- ^ Arthur MacCartney Shepard, Sea Power in Ancient History: The Story of the Navies of Classic Greece and Rome (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1924), 128.

- ^ James Harrison McKinney, Novel Ptolemaic naval power: Arsinoë II, Ptolemy II, and Cleopatra VII's innovative thalassocracies, Whitman College, p. 2. https://arminda.whitman.edu/theses/415

- ^ Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War, 5.34.6–7 & 9.

- ^ The Ptolemies, the Sea and the Nile: Studies in Waterborne Power, edited by Kostas Buraselis, Mary Stefanou, Dorothy J. Thompson, Cambridge University Press, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Robinson. pp.79–94.

- ^ Gera, Dov (1998). Judaea and Mediterranean Politics: 219 to 161 B.C.E. Leiden, Netherlands.: BRILL. p. 211. ISBN 9789004094413.

- ^ Robinson. pp.79-94.

- ^ Robinson, Carlos. Francis. (2019). "Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult". Chapter: Naval Power, the Ptolemies and the Maritime Aphrodite. pp.79–94. A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy. University of Queensland, Australia.

- ^ Muhs, Brian (2 August 2016). "7:The Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)". The Ancient Egyptian economy, 3000–30 BCE. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107113367.

- ^ Rickard.

- ^ James Harrison McKinney, Novel Ptolemaic naval power: Arsinoë II, Ptolemy II, and Cleopatra VII's innovative thalassocracies, Whitman College, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Muhs.

- ^ Fischer-Bovet, Christelle (2014). Army and Society in Ptolemaic Egypt. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 9781107007758.

- ^ Muhs, Brian (2 August 2016). "7:The Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE)". The Ancient Egyptian economy, 3000–30 BCE. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107113367.

- ^ Constantakopoulou, Christy (2017). Aegean Interactions: Delos and Its Networks in the Third Century. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780198787273.

- ^ Sidebotham, Steven E. (2019). Berenike and the Ancient Maritime Spice Route. Berkeley, California, United States.: University of California Press. p. 52. ISBN 9780520303386.

- ^ Kruse, Thomas (2013). "The Nile Police in the Ptolemaic Period", in: K. Buraselis – M. Stefanou – D.J. Thompson (Hg.), The Ptolemies, the Sea and the Nile. Studies in Waterborne Power, Cambridge 2013, 172–184". academia.edu. Cambridge University Press: 172–185. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- ^ Phillips, Heather A., "The Great Library of Alexandria?". Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010 Archived 2012-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Clarysse, Willy; Thompson, Dorothy J. (12 June 2006). Counting the People in Hellenistic Egypt: Volume 2, Historical Studies. Cambridge University Press. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-521-83839-9.

- ^ Chauveau, Michel (2000). Egypt in the age of Cleopatra : history and society under the Ptolemies. Cornell University Press. p. 34. ISBN 0-8014-3597-8. OCLC 42578681.

- ^ Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1968, p. 45: "The third generation... understood very little, if any, Hebrew or Aramaic. Their native tongue was Greek."

- ^ Solomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews, The Jewish Publication Society of America, Philadelphia, 1968, p. 46: "The Jews of Egypt looked upon the translation of the Bible into Greek as such an important event that they surrounded it later with a halo of legend... The story is told... by a certain Aristeas of Alexandria, that the second Ptolemy... sent ambassadors to the high priest in Jerusalem, and asked that a copy of these books be sent to him along with men capable of rendering them into Greek. The high priest did so, sending seventy-two... scribes and a copy of the Torah."

- ^ Flavius Josephus "Antiquities of the Jews" Book 12 Ch. 2

- ^ The Antiquities of the Jews, Flavius Josephus, Book 12;chapter2

- ^ Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads, Prof. Jan Retso, Page: 301

- ^ A History of the Arabs in the Sudan: The inhabitants of the northern Sudan before the time of the Islamic invasions. The progress of the Arab tribes through Egypt. The Arab tribes of the Sudan at the present day, Sir Harold Alfred MacMichael, Cambridge University Press, 1922, Page: 7

- ^ History of Egypt, Sir John Pentland Mahaffy, p. 20-21

- ^ King, Arienne (25 July 2018). "The Economy of Ptolemaic Egypt". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ von Reden, Sitta (2006). "The Ancient Economy and Ptolemaic Egypt". Ancient Economies, Modern Methodologies. Vol. 12 of Pragmateiai Series. Edipuglia. pp. 161–177.

Sources

edit- Burstein, Stanley Meyer (1 December 2007). The Reign of Cleopatra. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806138718. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Fletcher, Joann (2008), Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend, New York: Harper, ISBN 978-0-06-058558-7.

- Grabbe, L. L. (2008). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period. Volume 2 – The Coming of the Greeks: The Early Hellenistic Period (335 – 175 BC). T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-03396-3.

- Grainger, John D. (2010). The Syrian Wars. Brill. pp. 281–328. ISBN 9789004180505.

- Hölbl, Günther (2000). A History of the Ptolemaic Empire. Translated by Saavedra, Tina. Routledge.

- Peters, F. E. (1970). The Harvest of Hellenism. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Rawles, Richard (2019). Callimachus. Bloomsbury Academic.

Further reading