The middle of the 20th century was marked by a significant and persistent increase in fertility rates in many countries, especially in the Western world. The term baby boom is often used to refer to this particular boom, generally considered to have started immediately after World War II, although some demographers place it earlier or during the war.[citation needed] This terminology led to those born during this baby boom being nicknamed the baby boom generation.

The boom coincided with a marriage boom.[3] The increase in fertility was driven primarily by a decrease in childlessness and an increase in parity progression to a second child. In most of the Western countries, progression to a third child and beyond declined, which, coupled with aforementioned increase in transition to first and second child, resulted in higher homogeneity in family sizes. The baby boom was most prominent among educated and economically active women.[4][5]

The baby boom ended with a significant decline in fertility rates in the 1960s and 1970s, later called the baby bust by demographers.[6]

Causes

editEconomist and demographer Richard Easterlin in his "Twentieth Century American Population Growth" (2000), explains the growth pattern of the American population in the 20th century by examining the fertility rate fluctuations and the decreasing mortality rate. Easterlin attempts to prove the cause of the baby boom and baby bust by the "relative income" theory, despite the various other theories that these events have been attributed to. The "relative income" theory suggests that couples choose to have children based on a couple's ratio of potential earning power and the desire to obtain material objects. This ratio depends on the economic stability of the country and how people are raised to value material objects. The "relative income" theory explains the baby boom by suggesting that the late 1940s and the 1950s brought low desires to have material objects, because of the Great Depression and World War II, as well as plentiful job opportunities (being a post-war period). These two factors gave rise to a high relative income, which encouraged high fertility. Following this period, the next generation had a greater desire for material objects, however, an economic slowdown in the United States made jobs harder to acquire. This resulted in lower fertility rates causing the Baby Bust.[7]

Jan Van Bavel and David S. Reher proposed that the increase in nuptiality (marriage boom) coupled with low efficiency of contraception was the main cause of the baby boom. They doubted the explanations (including the Easterlin hypothesis) which considered the post-war economic prosperity that followed deprivation of the Great Depression as main cause of the baby boom, stressing that GDP-birth rate association was not consistent (positive before 1945 and negative after) with GDP growth accounting for a mere 5 percent of the variance in the crude birth rate over the period studied by the authors.[8] Data shows that only in a few countries was there a significant and persistent increase in the marital fertility index during the baby boom, which suggests that most of the increase in fertility was driven by the increase in marriage rates.[9]

Jona Schellekens claims that the rise in male earnings that started in the late 1930s accounts for most of the rise in marriage rates and that Richard Easterlin's hypothesis according to which a relatively small birth cohort entering the labor market caused the marriage boom is not consistent with data from the United States.[10]

Matthias Doepke, Moshe Hazan, and Yishay Maoz all argued that the baby boom was mainly caused by the alleged crowding out from the labor force of females who reached adulthood during the 1950s by females who started to work during the Second World War and did not quit their jobs after the economy recovered.[11] Andriana Bellou and Emanuela Cardia promote a similar argument, but they claim women who entered the labor force during the Great Depression crowded out women who participated in the baby boom.[12] Glenn Sandström disagrees with both variants of this interpretation based on the data from Sweden showing that an increase in nuptiality (which was one of the main causes of an increase in fertility) was limited to economically active women. He pointed out that in 1939 a law prohibiting the firing of a woman when she got married was passed in the country.[13]

Greenwood, Seshadri, and Vandenbroucke ascribe the baby boom to the diffusion of new household appliances that led to reduction of costs of childbearing.[14] However Martha J. Bailey and William J. Collins criticize their explanation on the basis that improvement of household technology began before baby boom, differences and changes in ownership of appliances and electrification in U.S. counties are negatively correlated with birth rates during baby boom, that the correlation between cohort fertility of the relevant women and access to electrical service in early adulthood is negative, and that Amish also experienced the baby boom.[15]

Judith Blake and Prithwis Das Gupta point out the increase in ideal family size in the times of baby boom.[16]

Peter Lindert partially attributed the baby boom to the extension of income tax to most of the US population in the early 1940s and newly created tax exemptions for children and married couples creating a new incentive for earlier marriage and higher fertility.[17] It is proposed that because the taxation was progressive the baby boom was more pronounced among the richer population.[18]

By region

editNorth America

editIn the United States and Canada, the baby boom was among the largest in the world.[19] In 1946, live births in the U.S. surged from 222,721 in January to 339,499 in October. By the end of the 1940s, about 32 million babies had been born, compared with 24 million in the 1930s. In 1954, annual births first topped four million and did not drop below that figure until 1965, by which time four out of ten Americans were under the age of 20.[20] As a result of the baby boom and traditional gender roles, getting married immediately after high school became commonplace and women increasingly encountered tremendous pressure to marry by the age of 20. A joke emerged at the time around comedic speculation that women were going to college to earn their MRS degree due to the increased marriage rate.[21]

The baby boom was stronger among American Catholics than among Protestants.[22]

The exact beginning and end of the baby boom is debated. The U.S. Census Bureau defines baby boomers as those born between mid-1946 and mid-1964,[2] although the U.S. birth rate began to increase in 1941, and decline after 1957. Deborah Carr considers baby boomers to be those born between 1944 and 1959,[23] while Strauss and Howe place the beginning of the baby boom in 1943.[24] In Canada the baby boom is usually defined as occurring from 1947 to 1966. Canadian soldiers were repatriated later than American servicemen, and Canada's birthrate did not start to rise until 1947. Most Canadian demographers prefer to use the later date of 1966 as the boom's end year in that country. The later end to the boom in Canada than in the US has been ascribed to a later adoption of birth control pills.[25][26]

In the United States, more babies were born during the seven years after 1948 than in the previous thirty, causing a shortage of teenage babysitters. At one point during this period, Madison, New Jersey only had fifty babysitters for its population of 8,000, dramatically increasing demand for sitters. In 1950, out of every $7 that a California couple spent to go to the movies, $5 went to paying a babysitter.[27]

Europe

editFrance and Austria experienced the strongest baby booms in Europe.[19] In contrast to most other countries, the French and Austrian baby booms were driven primarily by an increase in marital fertility.[28] In the French case, pronatalist policies were an important factor in this increase.[29] Weaker baby booms occurred in Germany, Switzerland, Belgium and the Netherlands.[30]

In the United Kingdom the baby boom occurred in two waves. After a short first wave of the baby boom during the war and immediately after, peaking in 1946, the United Kingdom experienced a second wave during the 1960s, with a peak in births in 1964 and a rapid fall after the Abortion Act 1967 came into force.[31]

The baby boom in Ireland began during the Emergency declared in the country during the Second World War.[32] Laws on contraception were restrictive in Ireland, and the baby boom was more prolonged in this country. Secular decline of fertility began only in the 1970s and particularly after the legalization of contraception in 1979. The marriage boom was even more prolonged and did not recede until the 1980s.[33]

The baby boom was very strong in Norway and Iceland, significant in Finland, moderate in Sweden and relatively weak in Denmark.[19]

Baby boom was absent or not very strong in Italy, Greece, Portugal and Spain.[19] There were however regional variations in Spain, with a considerable baby boom occurring in regions such as Catalonia.[34]

There was a strong baby boom in Czechoslovakia, but it was weak or absent in Poland, Bulgaria, Russia, Estonia and Lithuania, partly as a result of the Soviet famine of 1946–1947.[19][35]

Oceania

editThe volume of baby boom was the largest in the world in New Zealand and second-largest in Australia.[19] Like the US, the New Zealand baby boom was stronger among Catholics than Protestants.[36]

The author and columnist Bernard Salt places the Australian baby boom between 1946 and 1961.[37][38]

Asia and Africa

editMany countries outside the west (among them Morocco, China and Turkey) also witnessed the baby boom.[39] The baby boom in Mongolia is probably explained by improvement in health and living standards related to the adoption of technologies and modernisation.[40]

Latin America

editThere was also a baby boom in Latin American countries, excepting Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. An increase in fertility was driven by a decrease in childlessness and, in most nations, by an increase in parity progression to second, third and fourth births. Its magnitude was largest in Costa Rica and Panama.[41]

See also

editBibliography

edit- Barkan, Elliott Robert. From All Points: America's Immigrant West, 1870s–1952, (2007) 598 pages

- Barrett, Richard E., Donald J. Bogue, and Douglas L. Anderton. The Population of the United States 3rd Edition (1997) compendium of data

- Carter, Susan B., Scott Sigmund Gartner, Michael R. Haines, and Alan L. Olmstead, eds. The Historical Statistics of the United States (Cambridge UP: 6 vol; 2006) vol 1 on population; available online; massive data compendium; online version in Excel

- Chadwick Bruce A. and Tim B. Heaton, eds. Statistical Handbook on the American Family. (1992)

- Easterlin, Richard A. The American Baby Boom in Historical Perspective, (1962), the single most influential study complete text online[permanent dead link]

- Easterlin, Richard A. Birth and Fortune: The Impact of Numbers on Personal Welfare (1987), by leading economist excerpt and text search

- Gillon, Steve. Boomer Nation: The Largest and Richest Generation Ever, and How It Changed America (2004), by leading historian. excerpt and text search

- Hawes Joseph M. and Elizabeth I. Nybakken, eds. American Families: a Research Guide and Historical Handbook. (Greenwood Press, 1991)

- Klein, Herbert S. A Population History of the United States. Cambridge University Press, 2004. 316 pp

- Macunovich, Diane J. Birth Quake: The Baby Boom and Its Aftershocks (2002) excerpt and text search

- Mintz Steven and Susan Kellogg. Domestic Revolutions: a Social History of American Family Life. (1988)

- Wells, Robert V. Uncle Sam's Family (1985), general demographic history

- Weiss, Jessica. To Have and to Hold: Marriage, the Baby Boom, and Social Change (2000) excerpt and text search

References

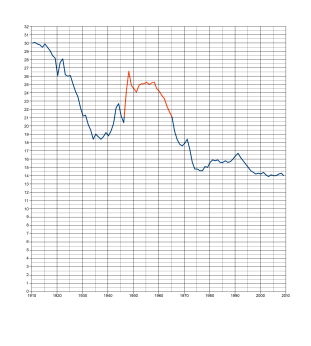

edit- ^ Pre-2003 data came from: "Table 1-1. Live Births, Birth Rates, and Fertility Rates, by Race: United States, 1909–2003". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (Retrieved from: "Vital Statistics of the United States, 2003, Volume I, Natality". CDC.) Post-2003 data came from: "National Vital Statistics Reports" (December 8, 2010). CDC. Volume 59, no. 1. The graph is an expanded SVG version of File:U.S.BirthRate.1909.2003.png

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fueled by Aging Baby Boomers, Nation's Older Population to Nearly Double in the Next 20 Years, Census Bureau Reports". United States Census Bureau. May 6, 2014.

- ^ Hajnal, John (April 1953). "The Marriage Boom". Population Index. 19 (2): 80–101. doi:10.2307/2730761. JSTOR 2730761.

- ^ Van Bavel, Jan; Klesment, Martin; Beaujouan, Eva; Brzozowska, Zuzanna; Puur, Allan (2018). "Seeding the gender revolution: Women's education and cohort fertility among the baby boom generations". Population Studies. 72 (3): 283–304. doi:10.1080/00324728.2018.1498223. PMID 30280973. S2CID 52911705.

- ^ Sandström, Glenn; Marklund, Emil (2018). "A prelude to the dual provider family – The changing role of female labor force participation and occupational field on fertility outcomes during the baby boom in Sweden 1900–60". The History of the Family. 24: 149–173. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2018.1556721.

- ^ Greenwood, Jeremy; Seshadri, Ananth; Vandenbroucke, Guillaume (2005). "The Baby Boom and Baby Bust" (PDF). American Economic Review. 95 (1): 183–207. doi:10.1257/0002828053828680.

- ^ See Richard A. Easterlin, Birth and Fortune: The Impact of Numbers on Personal Welfare (1987)

- ^ Van Bavel, Jan; Reher, David S. (2013). "The Baby Boom and Its Causes: What We Know and What We Need to Know". Population and Development Review. 39 (2): 257–288. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00591.x.

- ^ Sánchez-Barricarte, Jesús J. (2018). "Measuring and explaining the baby boom in the developed world in the mid-20th century" (PDF). Demographic Research. 38: 1203–1204. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.40.

- ^ Schellekens, Jona (2017). "The Marriage Boom and Marriage Bust in the United States: An Age-period-cohort Analysis". Population Studies. 71 (1): 65–82. doi:10.1080/00324728.2016.1271140. PMID 28209083. S2CID 41508881.

- ^ Doepke, Matthias; Hazan, Moshe; Maoz, Yishay D. (2015). "The Baby Boom and World War II: A Macroeconomic Analysis". Review of Economic Studies. 82 (3): 1031–1073. doi:10.3386/w13707.

- ^ Bellou, Andriana; Cardia, Emanuela (2014). "Baby-Boom, Baby-Bust and the Great Depression". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.665.133.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sandström, Glenn (November 2017). "A reversal of the socioeconomic gradient of nuptiality during the Swedish mid-20th-century baby boom" (PDF). Demographic Research. 37: 1625–1658. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.50.

- ^ Greenwood, Jeremy; Seshadri, Ananth; Vandenbroucke, Guillaume (2005). "The Baby Boom and Baby Bust". American Economic Review. 95 (1): 183–207. doi:10.1257/0002828053828680.

- ^ Bailey, Martha J.; Collins, William J. (2011). "Did Improvements in Household Technology Cause the Baby Boom? Evidence from Electrification, Appliance Diffusion, and the Amish" (PDF). American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics. 3 (2): 189–217. doi:10.1257/mac.3.2.189. S2CID 154327125.

- ^ Blake, Judith; Das Gupta, Prithwis (December 1975). "Reproductive Motivation Versus Contraceptive Technology: Is Recent American Experience an Exception?". Population and Development Review. 1 (2): 229–249. doi:10.2307/1972222. JSTOR 1972222.

- ^ Lindert, Peter H. (1978). Fertility and Scarcity in America. Princeton, New Jersey, USA: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400870066.

- ^ Zhao, Jackie Kai. "War Debt and the Baby Boom". Society for Economic Dynamics. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.205.8899.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Van Bavel, Jan; Reher, David S. (2013). "The Baby Boom and Its Causes: What We Know and What We Need to Know". Population and Development Review. 39 (2): 264–265. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00591.x.

- ^ Figures in Landon Y. Jones, "Swinging 60s?" in Smithsonian Magazine, January 2006, pp 102–107.

- ^ "People & Events: Mrs. America: Women's Roles in the 1950s". PBS. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ^ Westoff, Charles F.; Jones, Elise F. (1979). "The end of "Catholic" fertility". Demography. 16 (2): 209–217. doi:10.2307/2061139. JSTOR 2061139. PMID 456702.

- ^ Carr, Deborah (2002). "The Psychological Consequences of Work-Family Trade-Offs for Three Cohorts of Men and Women" (PDF). Social Psychology Quarterly. 65 (2): 103–124. doi:10.2307/3090096. JSTOR 3090096.

- ^ Strauss, William; Howe, Neil (1991). Generations: the history of America's future, 1584 to 2069. William Morrow & Co. p. 85. ISBN 0688119123.

- ^ The dates 1946 to 1962 are given in Doug Owram, Born at the right time: a history of the baby boom generation (1997)

- ^ David Foot, Boom, Bust and Echo: Profiting from the Demographic Shift in the 21st Century (1997) see Pearce, Tralee (June 24, 2006). "By definition: Boom, bust, X and why". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on August 7, 2006.

- ^ Forman-Brunell, Miriam (2009). Babysitter: An American History. New York University Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0-8147-2759-1.

- ^ Sánchez-Barricarte, Jesús J. (2018). "Measuring and explaining the baby boom in the developed world in the mid-20th century" (PDF). Demographic Research. 38: 1203–1204. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.40.

- ^ Calot, Gérard; Sardon, Jean-Paul (1998). "La vraie histoire du baby boom". Sociétal. 16: 41–44.

- ^ Frejka, Tomas (2017). "The Fertility Transition Revisited: A Cohort Perspective" (PDF). Comparative Population Studies. 42: 97. doi:10.12765/CPoS-2017-09en. S2CID 55080460.

- ^ Office for National Statistics Births in England and Wales: 2017

- ^ "Annual Report of the Registrar-General of Marriages, Births and Deaths in Ireland 1952" (PDF). Central Statistics Office. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Coleman, D. A. (1992). "The Demographic Transition in Ireland in International Context" (PDF). Proceedings of the British Academy. 79: 65.

- ^ Cabré, Anna; Torrents, Àngels (1990). "La Elevada nupcialidad como posible desencadenante de la transición demográfica en Cataluña" (PDF): 3–4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Frejka, Tomas (2017). "The Fertility Transition Revisited: A Cohort Perspective" (PDF). Comparative Population Studies. 42: 100. doi:10.12765/CPoS-2017-09en. S2CID 55080460.

- ^ Mol, Hans (1967). "Religion in New Zealand". Archives de sciences sociales des religions. 24: 123.

- ^ Salt, Bernard (2004). The Big Shift. South Yarra, Vic.: Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 978-1-74066-188-1.

- ^ Head, Neil; Arnold, Peter (November 2003). "Book Review: The Big Shift" (PDF). The Australian Journal of Emergency Management. 18 (4). Archived from the original on March 5, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Reher, David; Requena, Miguel (2014). "The mid-twentieth century fertility boom from a global perspective". The History of the Family. 20 (3): 420–445. doi:10.1080/1081602X.2014.944553. S2CID 154258701.

- ^ Spoorenberg, Thomas (2015). "Reconstructing historical fertility change in Mongolia: Impressive fertility rise before continued fertility decline" (PDF). Demographic Research. 33: 841–870. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2015.33.29.

- ^ Reher, David; Requena, Miguel (2014). "Was there a mid-20th-century fertility boom in latin america?" (PDF). Revista de Historia Economica – Journal of Iberian and Latin American Economic History. 32 (3): 319–350. doi:10.1017/S0212610914000172. hdl:10016/29916. S2CID 154726041.