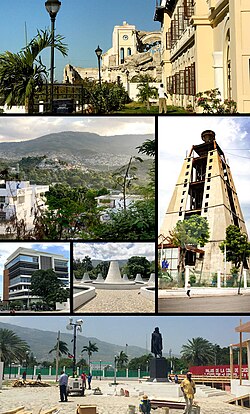

Port-au-Prince (/ˌpɔːrt oʊ ˈprɪns/ PORT oh PRINSS; French: [pɔʁ o pʁɛ̃s] ; Haitian Creole: Pòtoprens, [pɔtopɣɛ̃s]) is the capital and most populous city of Haiti. The city's population was estimated at 1,200,000 in 2022 with the metropolitan area estimated at a population of 2,618,894.[2] The metropolitan area is defined by the IHSI as including the communes of Port-au-Prince, Delmas, Cité Soleil, Tabarre, Carrefour, and Pétion-Ville.

Port-au-Prince

Pòtoprens | |

|---|---|

Capital city and commune | |

Port-au-Prince | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 18°32′N 72°20′W / 18.533°N 72.333°W | |

| Country | Haiti |

| Department | Ouest |

| Région | Gonave-Azuei |

| Arrondissement | Capitale-National |

| Founded | 1749 |

| Colonial seat | 1770 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Lucsonne Janvier |

| Area | |

| • Capital city and commune | 36.04 km2 (13.92 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 158.50 km2 (61.20 sq mi) |

| Population (2022 est.[2]) | |

| • Capital city and commune | 1,200,000 |

| • Density | 27,395/km2 (70,950/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 2,618,894[2] |

| • Metro density | 16,523/km2 (42,790/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Port-au-Princien(s) (masc.), Port-au-Princienne(s) (fem.) (en) and (fr) |

| Time zone | UTC-05:00 (Eastern Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-04:00 (Eastern Daylight Time) |

| Website | www |

The city of Port-au-Prince is on the Gulf of Gonâve: the bay on which the city lies, which acts as a natural harbor, has sustained economic activity since the civilizations of the Taíno. It was first incorporated under French colonial rule in 1749. The city's layout is similar to that of an amphitheater; commercial districts are near the water, while residential neighborhoods are located on the hills above. Its population is difficult to ascertain due to the rapid growth of slums in the hillsides above the city; however, recent estimates place the metropolitan area's population at around 3.7 million, nearly a third of the country's national population.[7] The city was catastrophically affected by a massive earthquake in 2010,[8] with large numbers of structures damaged or destroyed. Haiti's government estimated the death toll to be 230,000.[9] Gang violence is extensive, and kidnappings, massacres and gang rapes are common occurrences, often with the complicity of police officers and politicians.[10]

Etymology

editPort-au-Prince literally means "Prince's Port", but it is unclear which prince was the honoree. A theory is that the place is named after Le Prince, a ship captained by de Saint-André which arrived in the area in 1706. However, the islets in the bay had already been known as les îlets du Prince as early as 1680, predating the ship's arrival.[11] Furthermore, the port and the surrounding region continued to be known as Hôpital, named after the filibusters' hospital.[12]

French colonial commissioner Étienne Polverel named the city Port-Républicain on 23 September 1793 "in order that the inhabitants be kept continually in mind of the obligations which the French Revolution imposed on them." It was later renamed back to Port-au-Prince by Jacques I, Emperor of Haiti.[13]

When Haiti was divided between a kingdom in the north and a republic in the south, Port-au-Prince was the capital of the republic, under the leadership of Alexandre Pétion. Henri Christophe renamed the city Port-aux-Crimes after the assassination of Jacques I at Pont Larnage (now known as Pont-Rouge, and located north of the city).[citation needed]

History

editTaino Period

editThe Port-au-Prince area was part of the Xaragua chiefdom with the capital city, Yaguana being in Léoganes. There were multiple Taino settlements in the area such as Bohoma and Guahaba. It is understood that most of the plain area was used as hunting grounds. The Bahoruco mountain range in the north-east of Port-au-Prince was the scene of a Taino rebellion led by Enriquillo resulting in a treaty with the Spanish.

Spanish colonization

editPrior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus, the island of Hispaniola was inhabited by the Taíno people, who arrived in approximately 2600 BC in large dugout canoes. They are believed to come primarily from what is now eastern Venezuela. By the time Columbus arrived in 1492 AD, the region was under the control of Bohechio, Taíno cacique (chief) Xaragua.[14] He, like his predecessors, feared settling too close to the coast; such settlements would have proven to be tempting targets for the Caribs, who lived on neighboring islands. Instead, the region served as a hunting ground. The population of the region was approximately 400,000 at the time, but the Taínos were gone within 30 years of the arrival of the Spaniards.[15]

With the arrival of the Spaniards, the Amerindians were forced to accept a protectorate, and Bohechio, childless at death, was succeeded by his sister, Anacaona, wife of the cacique Caonabo. The Spanish insisted on larger tributes.[16] Eventually, the Spanish colonial administration decided to rule directly, and in 1503, Nicolas Ovando, then governor, set about to put an end to the régime headed by Anacaona.[citation needed] He invited her and other tribal leaders to a feast, and when the Amerindians had drunk a good deal of wine (the Spaniards did not drink on that occasion), he ordered most of the guests killed. Anacaona was spared, only to be hanged publicly some time later. Through violence, introduced diseases and murders, the Spanish settlers decimated the native population.[citation needed]

Direct Spanish rule over the area having been established, Ovando founded a settlement not far from the coast (west of Etang Saumâtre), ironically named Santa Maria de la Paz Verdadera, which would be abandoned several years later. Not long thereafter, Ovando founded Santa Maria del Puerto. The latter was first burned by French explorers in 1535, then again in 1592 by the English. These assaults proved to be too much for the Spanish colonial administration, and in 1606, it decided to abandon the region.[citation needed]

Domination of the filibustiers

editFor more than 50 years, the area that is today Port-au-Prince saw its population drop off drastically, when some buccaneers began to use it as a base, and Dutch merchants began to frequent it in search of leather, as game was abundant there. Around 1650, French flibustiers, running out of room on the Île de la Tortue, began to arrive on the coast, and established a colony at Trou-Borded. As the colony grew, they set up a hospital not far from the coast, on the Turgeau heights. This led to the region being known as Hôpital.

Although there had been no real Spanish presence in Hôpital for well over 50 years, Spain retained its formal claim to the territory, and the growing presence of the French flibustiers on ostensibly Spanish lands provoked the Spanish crown to dispatch Castilian soldiers to Hôpital to retake it. The mission proved to be a disaster for the Spanish, as they were outnumbered and outgunned, and in 1697, the Spanish government signed the Treaty of Ryswick, renouncing any claims to Hôpital. Around this time, the French also established bases at Ester (part of Petite Rivière) and Gonaïves.

Ester was a rich village, inhabited by merchants, and equipped with straight streets; it was here that the governor lived. On the other hand, the surrounding region, Petite-Rivière, was quite poor. Following a great fire in 1711, Ester was abandoned. Yet the French presence in the region continued to grow, and soon afterward, a new city was founded to the south, Léogâne.

While the first French presence in Hôpital, the region later to contain Port-au-Prince was that of the flibustiers; as the region became a real French colony, the colonial administration began to worry about the continual presence of these pirates. While useful in repelling foreign pirates, they were relatively independent, unresponsive to orders from the colonial administration, and a potential threat to it. Therefore, in the winter of 1707, Choiseul-Beaupré, the governor of the region sought to get rid of what he saw as a threat. He insisted upon control of the hospital, but the flibustiers refused, considering that humiliating. They proceeded to close the hospital rather than cede control of it to the governor, and many of them became habitans (farmers) the first long-term European inhabitants in the region.

Although the elimination of the flibustiers as a group from Hôpital reinforced the authority of the colonial administration, it also made the region a more attractive target for marauding buccaneers. In order to protect the area, in 1706, a captain named de Saint-André sailed into the bay just below the hospital, in a ship named Le Prince. It is said that M. de Saint-André named the area Port-au-Prince (meaning "Port of the Prince"), but the port and the surrounding region continued to be known as Hôpital, but the islets in the bay had already been known as les îlets du Prince as early as 1680.

Pirates eventually refrained from troubling the area, and various nobles sought land grants from the French crown in Hôpital; the first noble to control Hôpital was Sieur Joseph Randot. Upon his death in 1737, Sieur Pierre Morel gained control over part of the region, with Gatien Bretton des Chapelles acquiring another portion of it.

By then, the colonial administration was convinced that a capital needed to be chosen, in order to better control the French portion of Hispaniola (Saint-Domingue). For a time, Petit-Goâve and Léogâne vied for this honor, but both were eventually ruled out for various reasons. Neither was centrally located. Petit-Goâve's climate caused it to be too malarial, and Léogane's topography made it difficult to defend. Thus, in 1749, a new city was built, Port-au-Prince.

Foundation of Port-au-Prince

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2014) |

In 1770, Port-au-Prince replaced Cap-Français (the modern Cap-Haïtien) as capital of the colony of Saint-Domingue.[17]

In November 1791, it was burned in a battle between attacking black revolutionaries and defending white plantation owners.[18]

It was captured by British troops on 4 June 1794, after the Battle of Port-Républicain.[19]

In 1804, it became the capital of newly independent Haïti. When Jean-Jacques Dessalines was assassinated in 1806, Port-au-Prince became the capital of the mulatto-dominated south (Cap-Haïtien was the capital of the black-dominated north). It was re-established as the capital of all of Haiti when the country was unified again in 1820.[17]

American occupation

editDuring the American occupation of Haiti (1915–1934), Port-au-Prince, garrisoned by American Marines and Haitian gendarmes, was attacked twice by caco rebels. The first battle, which took place in 1919, was a victory of the American and Haitian government forces, as was the second attack in 1920.

2010 earthquake

editOn 12 January 2010, a 7.0 earthquake struck Port-au-Prince, devastating the city. Most of the central historic area of the city was destroyed, including Haiti's prized Cathédrale de Port-au-Prince, the capital building, Legislative Palace (the parliament building), Palace of Justice (Supreme Court building), several ministerial buildings, and at least one hospital.[20] The second floor of the Presidential Palace was thrown into the first floor, and the domes skewed at a severe tilt. The seaport and airport were both damaged, limiting aid shipments. The seaport was severely damaged by the quake[21] and was unable to accept aid shipments for the first week.

The airport's control tower was damaged[22] and the US military had to set up a new control center with generators to get the airport prepared for aid flights. Aid has been delivered to Port-au-Prince by numerous nations and voluntary groups as part of a global relief effort. On Wednesday 20 January 2010, an aftershock rated at a magnitude of 5.9 caused additional damage.[23] The City Hall (Mairie de Port-au-Prince) and most of the city's other government municipal buildings were destroyed in the 2010 earthquake.[24] Ralph Youri Chevry was the mayor of the city at the time of the earthquake.[25]

Hurricanes

editThe worst hurricane season experienced by Haiti occurred in 2008 when four storms Fay, Gustav, Hanna, and Ike negatively impacted Haiti. Nearly 800 people were killed; 22,000 homes were destroyed; 70% of the country's crops were lost, according to reliefweb.org. Then, in 2012, Hurricane Sandy, while not making direct impact, resulted in 75 deaths, $250 million in damage and a resurgence of cholera that was estimated to infected 5,000 people. In 2016, Hurricane Matthew caused catastrophic damage across Haiti, and over 500 deaths were associated with the storm in Haiti alone, along with at least $3 billion in damages. The storm also caused a massive humanitarian crisis shortly after. [26]

Geography

editThe metropolitan area is subdivided into various communes (districts). There is a ring of districts that radiates out from the commune of Port-au-Prince. Pétion-Ville is an affluent suburban commune located southeast of the city. Delmas is located directly south of the airport and north of the central city, and the rather poor commune of Carrefour is located southwest of the city.

The commune harbors many low-income slums plagued with poverty and violence in which the most notorious, Cité Soleil, is situated. However, Cité Soleil has been recently split off from Port-au-Prince proper to form a separate commune. The Champ de Mars area has begun some modern infrastructure development as of recently. The downtown area is the site of several projected modernization efforts in the capital.

Climate

editPort-au-Prince has a tropical wet and dry climate (Aw) and relatively constant temperatures throughout the course of the year. Port-au-Prince's wet season runs from March through November with rainfall peaking from April to May and from August to October, with the city experiencing a relative break in rainfall during the months of June and July. The city's dry season covers the remaining three months. Port-au-Prince generally experiences warm and humid conditions during the dry season and hot and humid conditions during the wet season.

| Climate data for Port-au-Prince | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31 (88) |

31 (88) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

33 (91) |

35 (95) |

35 (95) |

35 (95) |

34 (93) |

33 (91) |

32 (90) |

31 (88) |

33 (91) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27 (81) |

26.5 (79.7) |

27 (81) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

30 (86) |

30 (86) |

29.5 (85.1) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

27 (81) |

26.5 (79.7) |

28.0 (82.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 23 (73) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

23 (73) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

22 (72) |

23 (74) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 33 (1.3) |

58 (2.3) |

86 (3.4) |

160 (6.3) |

231 (9.1) |

102 (4.0) |

74 (2.9) |

145 (5.7) |

175 (6.9) |

170 (6.7) |

86 (3.4) |

33 (1.3) |

1,353 (53.3) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 3 | 5 | 7 | 11 | 13 | 8 | 7 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 99 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 279.0 | 254.2 | 279.0 | 273.0 | 251.1 | 237.0 | 279.0 | 282.1 | 246.0 | 251.1 | 240.0 | 244.9 | 3,116.4 |

| Source: Climate & Temperature[27] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editThe population of the area was 1,234,742.[28] The majority of the population is of African descent, but a prominent biracial minority controls many of the city's businesses.[citation needed] There are sizable numbers of residents, Asians, as well as a number of Europeans (both foreign-born and native-born).

Citizens of Arab (particularly Syrian, Lebanese, and Israeli Arab) ancestry have a large presence in the capital.[citation needed] Arab Haitians (a large number of whom live in Port-au-Prince) are, more often than not, concentrated in financial areas where the majority of them establish businesses. Most of the biracial residents of the city are concentrated within wealthier areas.

Notable people

edit- Édouard-Gérard Balbiani (1823–1899), French embryologist, was born in Port-au-Prince

- Stéphane Vincent, Haitian E-governance specialist

Economy

editPort-au-Prince is one of the nation's largest centers of economy and finance. The capital exports its most widely consumed produce of coffee and sugar, and has, in the past, exported other goods, such as shoes and baseballs. Port-au-Prince has food-processing plants as well as soap, textile and cement factories. Despite political unrest, the city also relies on the tourism industry and construction companies to move its economy. Port-au-Prince was once a popular place for cruises, but has lost nearly all of its tourism, and no longer has cruise ships coming into port.

Unemployment in Port-au-Prince is high, and compounded further by underemployment. Levels of economic activity remain prominent throughout the city, especially among people selling goods and services on the streets. Informal employment is believed to be widespread in Port-au-Prince's slums, as otherwise the population could not survive.[29] Port-au-Prince has several upscale districts in which crime rates are significantly lower than in the city center.[citation needed]

Port-au-Prince has a tourism industry. The Toussaint Louverture International Airport (referred to often as the Port-au-Prince International Airport) is the country's main international gateway for tourists. Tourists often visit the Pétion-Ville area of Port-au-Prince, with other sites of interest including gingerbread houses.

Health

editThere are a number of hospitals including le Centre Hospitalier du Sacré-Cœur,[30] Hôpital de l'Université d'État d'Haïti (l'HUEH), Centre Obstetrico Gynécologique Isaïe Jeanty-Léon Audain, Hôpital du Canapé-Vert, Hôpital Français (Asile Français), Hôpital Saint-François de Sales, Hôpital-Maternité Sapiens, Hôpital OFATMA, Clinique de la Santé, Maternité de Christ Roi, Centre Hospitalier Rue Berne and Maternité Mathieu.

After the 2010 earthquake, two hospitals remained that were operational. The University of Miami in partnership with Project Medishare has created a new hospital, L'Hôpital Bernard Mevs Project Medishare, to provide inpatient and outpatient care for those impacted by the January 2010 earthquake. This hospital is volunteer staffed and provides level 1 trauma care to Port-au-Prince and the surrounding regions.[31]

CDTI (Centre de Diagnostique et de Traitement Intégré) closed in April 2010 when international aid failed to materialize. It had been considered the country's premiere hospital.[32]

Culture

editThe culture of the city lies primarily in the center around the National Palace as well as its surrounding areas. The National Museum is located in the grounds of the palace, established in 1938. The National Palace was one of the early structures of the city but was destroyed and then rebuilt in 1918. It was destroyed again by the earthquake on 12 January 2010 which collapsed the center's domed roof.

Another popular destination in the capital is the Hotel Oloffson, a 19th-century gingerbread mansion that was once the private home of two former Haitian presidents. It has become a popular hub for tourist activity in the central city. The Cathédrale de Port-au-Prince is a famed site of cultural interest and attracts foreign visitors to its Neo-Romantic architectural style.

The Musée d'Art Haïtien du Collège Saint-Pierre contains work from some of the country's most talented artists, and the Musée National is a museum featuring historical artifacts such as King Henri Christophe's actual suicide pistol and a rusty anchor that museum operators claim was salvaged from Christopher Columbus's ship, the Santa María. Other notable cultural sites include the Archives Nationales, the Bibliothèque Nationale (National Library) and Expressions Art Gallery. The city is the birthplace of internationally known naïve artist Gesner Abelard, who was associated with the Centre d'Art. The Musée du Panthéon National Haïtien (MUPANAH) is a museum featuring the heroes of the independence of Haiti, the Haitian history and culture.

On 5 April 2015, the construction of a new LDS Temple in Port-au-Prince was announced.[33]

Port-au-Prince is the only city anywhere in the world to have a main avenue named for American abolitionist hero John Brown. Another is named for another abolitionist hero, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner.

Celebrations

editThere is a celebration of Bawon Samdi and Gran Brigi called Fet Gede, which takes place from the Day of the Dead on 1 November through the third day of the month. This occurs in the national cemetery of Haiti. While celebrating, people wear Vodou white cotton clothing and purple headscarves. During the celebration, the cemetery becomes packed with people. Those who are celebrating make sacrifices of food for the spirits (mange lwa) and pour liquor on the gravestones among other festivities.[34]

Government

editThe mayor of Port-au-Prince is Lucsonne Janvier, who succeeded Ralph Youri Chevry in July 2020.[35] In 2023, Janvier's City Hall employees protested lack of salaries.[36]

The city's separate districts (primarily the districts of Delmas, Carrefour, and Pétion-Ville) are all administered by their own municipal councils. The seat of the state, the Presidential Palace, is located in the Champ de Mars, square plaza of the city. The PNdH (Police Nationale d’Haïti) is the authority governing the enforcement of city laws.[citation needed]

The national police force as of recently, have been increasing in number. However, because of its ailing ineffectiveness and insufficient manpower, a significant number of UN personnel is present throughout the city as part of the stabilization mission in Haiti.[citation needed]

Education

editPort-au-Prince various educational institutions, ranging from small vocational schools to universities. Influential international schools in Port-au-Prince include Union School,[37] founded in 1919, and Quisqueya Christian School,[38] founded in 1974. Both schools offer an American-style pre-college education. French-speaking students can attend the Lycée Français (Lycée Alexandre Dumas), located in Bourdon. Another school is Anís Zunúzí Bahá'í School north west of Port-au-Prince which opened its doors in 1980[39] which survived the 2010 Haiti earthquake[40] and its staff were cooperating in relief efforts and sharing space and support with neighbors.[41]

A clinic was run at the school by a medical team from the United States and Canada.[42] Its classes offered transition from Haitian Creole to the French language but also a secondary language in English.[43] The State University of Haiti (Université d'État d'Haïti in French or UEH), is located within the capital along other universities such as the Quisqueya University and the Université des Caraïbes. There are many other institutions that observe the Haitian scholastic program. Many of them are religious academies led by foreign missionaries from France or Canada. These include Institution Saint-Louis de Gonzague, École Sainte-Rose-de-Lima, École Saint-Jean-Marie Vianney, Institution du Sacré-Coeur, and Collège Anne-Marie Javouhey.

The Ministry of Education is also located in downtown Port-au-Prince at the Palace of Ministries, adjacent to the National Palace in the Champ de Mars plaza.

The Haitian Group of Research and Pedagogical Activities (GHRAP) has set up several community centers for basic education. UNESCO's office at Port-au-Prince has taken a number of initiates in upgrading the educational facilities in Port-au-Prince.

Crime

editA 2012 independent study found that the murder rate in Port-au-Prince was 60.9 murders per 100,000 residents in February 2012.[44] In the 22 months after the end of the President Aristide era in 2004, the murder rate for Port-au-Prince reached a high of 219 murders per 100,000 residents per year.[45]

High-crime zones in the Port-au-Prince area include Croix-des-Bouquets, Cité Soleil, Carrefour, Bel Air, Martissant, the port road (Boulevard La Saline), urban route Nationale 1, the airport road (Boulevard Toussaint-Louverture) and its adjoining connectors to the New ("American") Road via Route Nationale 1. This latter area in particular has been the scene of numerous robberies, carjackings, and murders.[46]

In the Bel Air neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, the murder rate reached 50 murders per 100,000 residents at the end of 2011, up from 19 murders per 100,000 residents in 2010.[47]

Transportation

editRoads

editAll of the major transportation systems in Haiti are located near or run through the capital. The northern highway, Route Nationale #1 (National Highway One), originates in Port-au-Prince. The southern highway, Route Nationale #2 also runs through Port-au-Prince. Maintenance for these roads lapsed after the 1991 coup, prompting the World Bank to lend US$50 million designated for road repairs. The project was canceled in January 1999, however, after auditors revealed corruption.[citation needed] A third major highway, the Haitian Route Nationale #3, connects Port-au-Prince to the central plateau; however, due to its poor condition, it sees limited use.[citation needed]

Public transportation

editThe most common form of public transportation in Haiti is the use of brightly painted pickup trucks as taxis called "tap-taps."

Seaport

editThe seaport, Port international de Port-au-Prince, has more registered shipping than any of the over dozen ports in the country.[citation needed] The port's facilities include cranes, large berths, and warehouses, but these facilities are in universally poor shape. The port is underused,[citation needed] possibly due to the substantially high port fees compared to ports in the Dominican Republic.

Airports

editToussaint Louverture International Airport (Maïs Gâté), which opened in 1965 (as François Duvalier International Airport), is north of the city. It is Haiti's major jetway, and as such, handles the vast majority of the country's international flights. Transportation to smaller cities from the major airport is done via smaller aircraft. Companies providing this service include Caribintair and Sunrise Airways.

See also

edit- Enriquillo-Plantain Garden fault zone

- Famous people from Port-au-Prince

- Port au Prince – a ship from the Age of Sail

References

edit- ^ "Exposition Internationale, 1949–1950 – Bi-Centenaire de Port-au-Prince 1749–1949 (official catalog of the exhibition, printed in 200 copies)" (in French). University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Mars 2015 Population Totale, Population de 18 Ans et Plus Menages et Densites Estimes En 2015" (PDF). Institut Haïtien de Statistique et d’Informatique (IHSI). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ a b Smiley Anders (26 July 1978). "Visiting Haitian Mayor Seeking Builders for Housing Projects". Baton Rouge Morning Advocate (sec. A, p. 12).

- ^ Emily Glaser (29 March 2017). "Getting Down And Dirty With Two Of Charlotte's Freshest Garden Nonprofits". southcharlottelifestylepubs.com. Archived from the original on 2019-07-15. Retrieved 2018-05-02.

- ^ "Sister City International Listings". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on 2014-09-13. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- ^ "International Campaign for Compassionate Cities" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-01. Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ^ "Urbanres.net" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-01. Retrieved 2014-01-01.

- ^ [1] Archived 15 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Haiti Raises Earthquake's Death Toll to 230,000". Associated Press. 2010-02-09. Archived from the original on 2010-02-15. Retrieved 2010-02-10.

- ^ "Haiti: Inside the capital city taken hostage by brutal gangs" Archived 2022-12-05 at the Wayback Machine, by Orla Guerin, The Independent, 5 December 2022 (retrieved same date).

- ^ Janvier, Louis-Joseph (1883). La république d'Haïti et ses visiteurs (in French). Marpon et Flammarion. p. 66.

« Le nom de la ville […] lui vient d'un vaisseau nommé le Prince, qui mouilla dans la baie en 1706. » […] C'est inexact. […] les îlets qui sont dans la rade de Port-au-Prince portaient authentiquement le nom d'Îlets du Prince dès 1680, c'est-à-dire 26 ans avant que le navire le Prince, commandé par M. de Saint-André, ne fût venu prendre named le Prince, which anchored in the bay in 1706.' […] This is inaccurate. […] The islets in the harbour of Port-au-Prince in fact had been named Îlets du Prince in 1680, which was 26 years before Mr. de Saint-André's ship le Prince even anchored in the harbour."

- ^ Moreau de Saint-Méry, M. L.-É. (1876). Description topographique, physique, civile, politique et historique de la partie française de l'île Saint-Dominge (in French). Vol. 3. L. Guérin. p. 348.

la désignation du point où les flibustiers avaient formé un hôpital pour eux.

≈ "The naming of the spot where filibusters had founded a hospital for themselves." - ^ Jacques Nicolas Léger, Haiti: Her History and Her Detractors (The Neale Pub. Co., 1907), page 66

- ^ Accilien, Cécile; Adams, Jessica; Méléance, Elmide; Jean-Pierre, Ulrick (2006). Revolutionary freedoms: a history of survival, strength and imagination in Haiti. Coconut Creek, Florida: Caribbean Studies Press. pp. 19–23. ISBN 1-58432-293-4. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Gorry, Conner; Miller, Debra (1 October 2005). Caribbean Islands. Lonely Planet. pp. 245–246. ISBN 1-74104-055-8. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Wilson, Samuel M. (1990). Hispaniola: Caribbean Chiefdoms in the Age of Columbus. University of Alabama Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8173-0462-1.

The events of 1494 and early 1495 ultimately precipitated a collective and violent reaction from Indians in the western Vega. Colón took this as an opportunity to subjugate the island brutally and to establish a tribute system through which gold and food could be collected from the Indians in greater quantity.

- ^ a b Michael R. Hall (2012). Historical Dictionary of Haiti. Scarecrow Press. pp. 210–211. ISBN 9780810875494. Archived from the original on 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ^ "The Haitian Revolution". Archived from the original on 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2014-09-10.

- ^ Madiou, Thomas (1847). Histoire d'Haïti, Tome I (in French). pp. 186–188.

- ^ "Haïti — séisme : les principaux bâtiments publics effondrés lors du séisme" (in French). Haiti Press Network. 30 January 2010. Archived from the original on 26 March 2010. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ^ CNN, Anderson Cooper 360, 18 January 2010

- ^ New York Times, "Devastation, Seen From a Ship" Archived 2010-01-17 at the Wayback Machine, Eric Lipton, 13 January 2010 (accessed 15 January 2010)

- ^ Bhatt, Aishwarya (2010-01-13). "Presidential Palace Ruined in the Earthquake. Over 200,000 dead" Archived 2010-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Roig-Franzia, Manuel (2010-01-20). "Shattered city government in quake-ravaged Port-au-Prince in need of help itself". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2018-12-11. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ "Trapped Haitian Girl Dies Despite Rescue Effort". New York Times. Associated Press. 2010-01-14. Archived from the original on 2020-04-23. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ "Hurricane Matthew makes landfall on impoverished Haiti". USA Today. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ^ "Port-Au-Prince, Haiti". Climate & Temperature. Archived from the original on 21 July 2019. Retrieved 2 September 2012.

- ^ "Biggest Cities Haiti". Archived from the original on 2010-03-25. Retrieved 2010-05-27.

- ^ Simon M. Fass's research book, Political Economy in Haïti: The Drama of Survival

- ^ "Centre Hospitalier du Sacré-Cœur". Archived from the original on 2012-09-29. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ^ "Project Medishare For Haiti – Saving Lives, Rebuilding Hope | Project Medishare". Archived from the original on 2010-05-14. Retrieved 2010-03-08.

- ^ Torres, Jose A. (2010-07-18). "Lack of funds force hospital to shut down". floridatoday.com. Archived from the original on 2014-09-11. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- ^ Monson, Thomas. "3 new LDS temples to be built in Ivory Coast, Haiti and Thailand, President Monson says". Deseret News. Archived from the original on 5 April 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ Evans Braziel, Jana (2017). Riding with Death, Vodou Art and Urban Ecology in the Streets of Port-au-Prince. University Press of Mississippi. p. 56. ISBN 9781496812759.

- ^ "Lucsonne Janvier est nommé à la tête de la Mairie de Port-au-Prince". Haiti Standard (in French). 8 July 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ Arnault, Veron; Sanon, Yasmine (24 January 2023). "Des employés de la Mairie de Port-au-Prince réclament leur salaire". Le National (in French). Archived from the original on 26 July 2023. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ "Haiti, Port-au-Prince: Union School". Office of Overseas Schools. United States Department of State. 2007-10-26. Retrieved 2008-11-29.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Quisqueya Christian School". Quisqueya Christian School. Archived from the original on 2009-01-23. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ^ "About The School". Anis Zunuzi Baha'i School. Anís Zunúzí Bahá'í School. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ Thimm, Hans J., ed. (2010). "Anís Zunúzí Bahá'í School". Facebook. Retrieved 2010-02-06.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "New Events and Updates". Projects & Initiatives; Projects we support; Anis Zunuzi School. Mona Foundation. 2009. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ "Amid wreckage in Haiti, new birth brings hope". Bahá'í World News Service. Bahá'i International Community. 5 February 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-06-02. Retrieved 2010-02-06.

- ^ "Development: A look at programs around the world; Americas; Agriculture and forestry;". Baháʼí News. No. 682. January 1987. p. 4. ISSN 0195-9212.

- ^ Kolbe & Muggah 2012, p. 3.

- ^ "Kolbe: Political and Social Marginalization Behind Increases in Crime", Haiti: Relief and Reconstruction Watch Archived 2015-04-17 at the Wayback Machine, Center for Economic and Policy Research, 22 March 2012.

- ^ "Haiti: Country-Specific Information". Archived 2015-09-05 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Department of State (4 December 2014). Accessed 12 April 2015. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain..

- ^ Kolbe & Muggah 2012, p. 4.

Bibliography

edit- Kolbe, Athena R.; Muggah, Robert (2012). ""Haiti's Urban Crime Wave? Results from Monthly Household Surveys August 2011 – February 2012" (PDF). Rio de Janeiro: Instituto Igarape. Kolbe, Athena R & Muggah, Robert. p. 9. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

External links

edit- Port-au-Prince travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Tour Virtual of Port au Prince – Brazilian Site

- Port-au-Prince U.S Embassy

- Live Radios from Haiti

- "Scientists: Why Haiti Should Move Its Capital". Time magazine