In geometry, a polyhedron (pl.: polyhedra or polyhedrons; from Greek πολύ (poly-) 'many' and ἕδρον (-hedron) 'base, seat') is a three-dimensional figure with flat polygonal faces, straight edges and sharp corners or vertices.

| Definition | A three-dimensional example of the more general polytope in any number of dimensions |

|---|---|

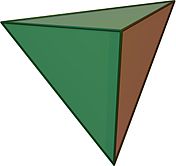

A convex polyhedron is a polyhedron that bounds a convex set. Every convex polyhedron can be constructed as the convex hull of its vertices, and for every finite set of points, not all on the same plane, the convex hull is a convex polyhedron. Cubes and pyramids are examples of convex polyhedra.

A polyhedron is a generalization of a 2-dimensional polygon and a 3-dimensional specialization of a polytope, a more general concept in any number of dimensions.

Definition

editConvex polyhedra are well-defined, with several equivalent standard definitions. However, the formal mathematical definition of polyhedra that are not required to be convex has been problematic. Many definitions of "polyhedron" have been given within particular contexts,[1] some more rigorous than others, and there is no universal agreement over which of these to choose. Some of these definitions exclude shapes that have often been counted as polyhedra (such as the self-crossing polyhedra) or include shapes that are often not considered as valid polyhedra (such as solids whose boundaries are not manifolds). As Branko Grünbaum observed,

"The Original Sin in the theory of polyhedra goes back to Euclid, and through Kepler, Poinsot, Cauchy and many others ... at each stage ... the writers failed to define what are the polyhedra".[2]

Nevertheless, there is general agreement that a polyhedron is a solid or surface that can be described by its vertices (corner points), edges (line segments connecting certain pairs of vertices), faces (two-dimensional polygons), and that it sometimes can be said to have a particular three-dimensional interior volume. One can distinguish among these different definitions according to whether they describe the polyhedron as a solid, whether they describe it as a surface, or whether they describe it more abstractly based on its incidence geometry.[3]

- A common and somewhat naive definition of a polyhedron is that it is a solid whose boundary can be covered by finitely many planes[4][5] or that it is a solid formed as the union of finitely many convex polyhedra.[6] Natural refinements of this definition require the solid to be bounded, to have a connected interior, and possibly also to have a connected boundary. The faces of such a polyhedron can be defined as the connected components of the parts of the boundary within each of the planes that cover it, and the edges and vertices as the line segments and points where the faces meet. However, the polyhedra defined in this way do not include the self-crossing star polyhedra, whose faces may not form simple polygons, and some of whose edges may belong to more than two faces.[7]

- Definitions based on the idea of a bounding surface rather than a solid are also common.[8] For instance, O'Rourke (1993) defines a polyhedron as a union of convex polygons (its faces), arranged in space so that the intersection of any two polygons is a shared vertex or edge or the empty set and so that their union is a manifold.[9] If a planar part of such a surface is not itself a convex polygon, O'Rourke requires it to be subdivided into smaller convex polygons, with flat dihedral angles between them. Somewhat more generally, Grünbaum defines an acoptic polyhedron to be a collection of simple polygons that form an embedded manifold, with each vertex incident to at least three edges and each two faces intersecting only in shared vertices and edges of each.[10] Cromwell's Polyhedra gives a similar definition but without the restriction of at least three edges per vertex. Again, this type of definition does not encompass the self-crossing polyhedra.[8] Similar notions form the basis of topological definitions of polyhedra, as subdivisions of a topological manifold into topological disks (the faces) whose pairwise intersections are required to be points (vertices), topological arcs (edges), or the empty set. However, there exist topological polyhedra (even with all faces triangles) that cannot be realized as acoptic polyhedra.[11]

- One modern approach is based on the theory of abstract polyhedra. These can be defined as partially ordered sets whose elements are the vertices, edges, and faces of a polyhedron. A vertex or edge element is less than an edge or face element (in this partial order) when the vertex or edge is part of the edge or face. Additionally, one may include a special bottom element of this partial order (representing the empty set) and a top element representing the whole polyhedron. If the sections of the partial order between elements three levels apart (that is, between each face and the bottom element, and between the top element and each vertex) have the same structure as the abstract representation of a polygon, then these partially ordered sets carry exactly the same information as a topological polyhedron.[citation needed] However, these requirements are often relaxed, to instead require only that sections between elements two levels apart have the same structure as the abstract representation of a line segment.[12] (This means that each edge contains two vertices and belongs to two faces, and that each vertex on a face belongs to two edges of that face.) Geometric polyhedra, defined in other ways, can be described abstractly in this way, but it is also possible to use abstract polyhedra as the basis of a definition of geometric polyhedra. A realization of an abstract polyhedron is generally taken to be a mapping from the vertices of the abstract polyhedron to geometric points, such that the points of each face are coplanar. A geometric polyhedron can then be defined as a realization of an abstract polyhedron.[13] Realizations that omit the requirement of face planarity, that impose additional requirements of symmetry, or that map the vertices to higher dimensional spaces have also been considered.[12] Unlike the solid-based and surface-based definitions, this works perfectly well for star polyhedra. However, without additional restrictions, this definition allows degenerate or unfaithful polyhedra (for instance, by mapping all vertices to a single point) and the question of how to constrain realizations to avoid these degeneracies has not been settled.

In all of these definitions, a polyhedron is typically understood as a three-dimensional example of the more general polytope in any number of dimensions. For example, a polygon has a two-dimensional body and no faces, while a 4-polytope has a four-dimensional body and an additional set of three-dimensional "cells". However, some of the literature on higher-dimensional geometry uses the term "polyhedron" to mean something else: not a three-dimensional polytope, but a shape that is different from a polytope in some way. For instance, some sources define a convex polyhedron to be the intersection of finitely many half-spaces, and a polytope to be a bounded polyhedron.[14][15] The remainder of this article considers only three-dimensional polyhedra.

Convex polyhedra

editA convex polyhedron is a polyhedron that forms a convex set as a solid. That being said, it is a three-dimensional solid whose every line segment connects two of its points lies its interior or on its boundary; none of its faces are coplanar (they do not share the same plane) and none of its edges are collinear (they are not segments of the same line).[16][17] A convex polyhedron can also be defined as a bounded intersection of finitely many half-spaces, or as the convex hull of finitely many points, in either case, restricted to intersections or hulls that have nonzero volume.[14][15]

Important classes of convex polyhedra include the family of prismatoid, the Platonic solids, the Archimedean solids and their duals the Catalan solids, and the regular polygonal faces polyhedron. The prismatoids are the polyhedron whose vertices lie on two parallel planes and their faces are likely to be trapezoids and triangles.[18] Examples of prismatoids are pyramids, wedges, parallelipipeds, prisms, antiprisms, cupolas, and frustums. The Platonic solids are the five ancientness polyhedrons—tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron, cube, and dodecahedron—classified by Plato in his Timaeus whose connecting four classical elements of nature.[19] The Archimedean solids are the class of thirteen polyhedrons whose faces are all regular polygons and whose vertices are symmetric to each other;[a] their dual polyhedrons are Catalan solids.[21] The class of regular polygonal faces polyhedron are the deltahedron (whose faces are all equilateral triangles and Johnson solids (whose faces are arbitrary regular polygons).[22][23]

The convex polyhedron can be categorized into elementary polyhedron or composite polyhedron. An elementary polyhedron is a convex regular-faced polyhedron that cannot be produced into two or more polyhedrons by slicing it with a plane.[24] Quite opposite to a composite polyhedron, it can be alternatively defined as a polyhedron that can be constructed by attaching more elementary polyhedrons. For example, triaugmented triangular prism is a composite polyhedron since it can be constructed by attaching three equilateral square pyramids onto the square faces of a triangular prism; the square pyramids and the triangular prism are elementary.[25]

A midsphere of a convex polyhedron is a sphere tangent to every edge of a polyhedron, an intermediate sphere in radius between the insphere and circumsphere, for polyhedra for which all three of these spheres exist. Every convex polyhedron is combinatorially equivalent to a canonical polyhedron, a polyhedron that has a midsphere whose center coincides with the centroid of the polyhedron. The shape of the canonical polyhedron (but not its scale or position) is uniquely determined by the combinatorial structure of the given polyhedron.[26]

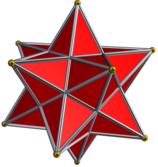

Some polyhedrons do not have the property of convexity, and they are called non-convex polyhedrons. Such polyhedrons are star polyhedrons and Kepler–Poinsot polyhedrons, which constructed by either stellation (process of extending the faces—within their planes—so that they meet) or faceting (whose process of removing parts of a polyhedron to create new faces—or facets—without creating any new vertices).[27][28] A facet of a polyhedron is any polygon whose corners are vertices of the polyhedron, and is not a face.[27] The stellation and faceting are inverse or reciprocal processes: the dual of some stellation is a faceting of the dual to the original polyhedron.

Characteristics

editNumber of faces

editPolyhedra may be classified and are often named according to the number of faces. The naming system is based on Classical Greek, and combines a prefix counting the faces with the suffix "hedron", meaning "base" or "seat" and referring to the faces. For example a tetrahedron is a polyhedron with four faces, a pentahedron is a polyhedron with five faces, a hexahedron is a polyhedron with six faces, etc.[29] For a complete list of the Greek numeral prefixes see Numeral prefix § Table of number prefixes in English, in the column for Greek cardinal numbers. The names of tetrahedra, hexahedra, octahedra (8-sided polyhedra), dodecahedra (12-sided polyhedra), and icosahedra (20-sided polyhedra) are sometimes used without additional qualification to refer to the Platonic solids, and sometimes used to refer more generally to polyhedra with the given number of sides without any assumption of symmetry.[30]

Topological classification

editSome polyhedra have two distinct sides to their surface. For example, the inside and outside of a convex polyhedron paper model can each be given a different colour (although the inside colour will be hidden from view). These polyhedra are orientable. The same is true for non-convex polyhedra without self-crossings. Some non-convex self-crossing polyhedra can be coloured in the same way but have regions turned "inside out" so that both colours appear on the outside in different places; these are still considered to be orientable. However, for some other self-crossing polyhedra with simple-polygon faces, such as the tetrahemihexahedron, it is not possible to colour the two sides of each face with two different colours so that adjacent faces have consistent colours. In this case the polyhedron is said to be non-orientable. For polyhedra with self-crossing faces, it may not be clear what it means for adjacent faces to be consistently coloured, but for these polyhedra it is still possible to determine whether it is orientable or non-orientable by considering a topological cell complex with the same incidences between its vertices, edges, and faces.[31]

A more subtle distinction between polyhedron surfaces is given by their Euler characteristic, which combines the numbers of vertices , edges , and faces of a polyhedron into a single number defined by the formula

The same formula is also used for the Euler characteristic of other kinds of topological surfaces. It is an invariant of the surface, meaning that when a single surface is subdivided into vertices, edges, and faces in more than one way, the Euler characteristic will be the same for these subdivisions. For a convex polyhedron, or more generally any simply connected polyhedron with surface a topological sphere, it always equals 2. For more complicated shapes, the Euler characteristic relates to the number of toroidal holes, handles or cross-caps in the surface and will be less than 2.[32] All polyhedra with odd-numbered Euler characteristic are non-orientable. A given figure with even Euler characteristic may or may not be orientable. For example, the one-holed toroid and the Klein bottle both have , with the first being orientable and the other not.[31]

For many (but not all) ways of defining polyhedra, the surface of the polyhedron is required to be a manifold. This means that every edge is part of the boundary of exactly two faces (disallowing shapes like the union of two cubes that meet only along a shared edge) and that every vertex is incident to a single alternating cycle of edges and faces (disallowing shapes like the union of two cubes sharing only a single vertex). For polyhedra defined in these ways, the classification of manifolds implies that the topological type of the surface is completely determined by the combination of its Euler characteristic and orientability. For example, every polyhedron whose surface is an orientable manifold and whose Euler characteristic is 2 must be a topological sphere.[31]

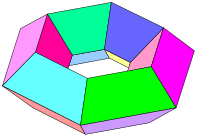

A toroidal polyhedron is a polyhedron whose Euler characteristic is less than or equal to 0, or equivalently whose genus is 1 or greater. Topologically, the surfaces of such polyhedra are torus surfaces having one or more holes through the middle.[33]

Duality

editFor every convex polyhedron, there exists a dual polyhedron having

- faces in place of the original's vertices and vice versa, and

- the same number of edges.

The dual of a convex polyhedron can be obtained by the process of polar reciprocation.[34] Dual polyhedra exist in pairs, and the dual of a dual is just the original polyhedron again. Some polyhedra are self-dual, meaning that the dual of the polyhedron is congruent to the original polyhedron.[35]

Abstract polyhedra also have duals, obtained by reversing the partial order defining the polyhedron to obtain its dual or opposite order.[13] These have the same Euler characteristic and orientability as the initial polyhedron. However, this form of duality does not describe the shape of a dual polyhedron, but only its combinatorial structure. For some definitions of non-convex geometric polyhedra, there exist polyhedra whose abstract duals cannot be realized as geometric polyhedra under the same definition.[10]

Vertex figures

editFor every vertex one can define a vertex figure, which describes the local structure of the polyhedron around the vertex. Precise definitions vary, but a vertex figure can be thought of as the polygon exposed where a slice through the polyhedron cuts off a vertex.[8] For the Platonic solids and other highly-symmetric polyhedra, this slice may be chosen to pass through the midpoints of each edge incident to the vertex,[36] but other polyhedra may not have a plane through these points. For convex polyhedra, and more generally for polyhedra whose vertices are in convex position, this slice can be chosen as any plane separating the vertex from the other vertices.[37] When the polyhedron has a center of symmetry, it is standard to choose this plane to be perpendicular to the line through the given vertex and the center;[38] with this choice, the shape of the vertex figure is determined up to scaling. When the vertices of a polyhedron are not in convex position, there will not always be a plane separating each vertex from the rest. In this case, it is common instead to slice the polyhedron by a small sphere centered at the vertex.[39] Again, this produces a shape for the vertex figure that is invariant up to scaling. All of these choices lead to vertex figures with the same combinatorial structure, for the polyhedra to which they can be applied, but they may give them different geometric shapes.

Surface area and distances

editThe surface area of a polyhedron is the sum of areas of its faces, for definitions of polyhedra for which the area of a face is well-defined. The geodesic distance between any two points on the surface of a polyhedron measures the length of the shortest curve that connects the two points, remaining within the surface. By Alexandrov's uniqueness theorem, every convex polyhedron is uniquely determined by the metric space of geodesic distances on its surface. However, non-convex polyhedra can have the same surface distances as each other, or the same as certain convex polyhedra.[40]

Volume

editPolyhedral solids have an associated quantity called volume that measures how much space they occupy. Simple families of solids may have simple formulas for their volumes; for example, the volumes of pyramids, prisms, and parallelepipeds can easily be expressed in terms of their edge lengths or other coordinates. (See Volume § Volume formulas for a list that includes many of these formulas.)

Volumes of more complicated polyhedra may not have simple formulas. Volumes of such polyhedra may be computed by subdividing the polyhedron into smaller pieces (for example, by triangulation). For example, the volume of a regular polyhedron can be computed by dividing it into congruent pyramids, with each pyramid having a face of the polyhedron as its base and the centre of the polyhedron as its apex.

In general, it can be derived from the divergence theorem that the volume of a polyhedral solid is given by where the sum is over faces F of the polyhedron, QF is an arbitrary point on face F, NF is the unit vector perpendicular to F pointing outside the solid, and the multiplication dot is the dot product.[41] In higher dimensions, volume computation may be challenging, in part because of the difficulty of listing the faces of a convex polyhedron specified only by its vertices, and there exist specialized algorithms to determine the volume in these cases.[42]

Dehn invariant

editIn two dimensions, the Bolyai–Gerwien theorem asserts that any polygon may be transformed into any other polygon of the same area by cutting it up into finitely many polygonal pieces and rearranging them. The analogous question for polyhedra was the subject of Hilbert's third problem. Max Dehn solved this problem by showing that, unlike in the 2-D case, there exist polyhedra of the same volume that cannot be cut into smaller polyhedra and reassembled into each other. To prove this Dehn discovered another value associated with a polyhedron, the Dehn invariant, such that two polyhedra can only be dissected into each other when they have the same volume and the same Dehn invariant. It was later proven by Sydler that this is the only obstacle to dissection: every two Euclidean polyhedra with the same volumes and Dehn invariants can be cut up and reassembled into each other.[43] The Dehn invariant is not a number, but a vector in an infinite-dimensional vector space, determined from the lengths and dihedral angles of a polyhedron's edges.[44]

Another of Hilbert's problems, Hilbert's 18th problem, concerns (among other things) polyhedra that tile space. Every such polyhedron must have Dehn invariant zero.[45] The Dehn invariant has also been connected to flexible polyhedra by the strong bellows theorem, which states that the Dehn invariant of any flexible polyhedron remains invariant as it flexes.[46]

Symmetries

editMany of the most studied polyhedra are highly symmetrical, that is, their appearance is unchanged by some reflection or rotation of space. Each such symmetry may change the location of a given vertex, face, or edge, but the set of all vertices (likewise faces, edges) is unchanged. The collection of symmetries of a polyhedron is called its symmetry group.

All the elements that can be superimposed on each other by symmetries are said to form a symmetry orbit. For example, all the faces of a cube lie in one orbit, while all the edges lie in another. If all the elements of a given dimension, say all the faces, lie in the same orbit, the figure is said to be transitive on that orbit. For example, a cube is face-transitive, while a truncated cube has two symmetry orbits of faces.

The same abstract structure may support more or less symmetric geometric polyhedra. But where a polyhedral name is given, such as icosidodecahedron, the most symmetrical geometry is often implied.[citation needed]

There are several types of highly symmetric polyhedron, classified by which kind of element – faces, edges, or vertices – belong to a single symmetry orbit:

- Regular: vertex-transitive, edge-transitive and face-transitive. (This implies that every face is the same regular polygon; it also implies that every vertex is regular.)

- Quasi-regular: vertex-transitive and edge-transitive (and hence has regular faces) but not face-transitive. A quasi-regular dual is face-transitive and edge-transitive (and hence every vertex is regular) but not vertex-transitive.

- Semi-regular: vertex-transitive but not edge-transitive, and every face is a regular polygon. (This is one of several definitions of the term, depending on author. Some definitions overlap with the quasi-regular class.) These polyhedra include the semiregular prisms and antiprisms. A semi-regular dual is face-transitive but not vertex-transitive, and every vertex is regular.

- Uniform: vertex-transitive and every face is a regular polygon, i.e., it is regular, quasi-regular or semi-regular. A uniform dual is face-transitive and has regular vertices, but is not necessarily vertex-transitive.

- Isogonal: vertex-transitive.

- Isotoxal: edge-transitive.

- Isohedral: face-transitive.

- Noble: face-transitive and vertex-transitive (but not necessarily edge-transitive). The regular polyhedra are also noble; they are the only noble uniform polyhedra. The duals of noble polyhedra are themselves noble.

Some classes of polyhedra have only a single main axis of symmetry. These include the pyramids, bipyramids, trapezohedra, cupolae, as well as the semiregular prisms and antiprisms.

Regular polyhedra

editRegular polyhedra are the most highly symmetrical. Altogether there are nine regular polyhedra: five convex and four star polyhedra.

The five convex examples have been known since antiquity and are called the Platonic solids. These are the triangular pyramid or tetrahedron, cube, octahedron, dodecahedron and icosahedron:

There are also four regular star polyhedra, known as the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra after their discoverers.

The dual of a regular polyhedron is also regular.

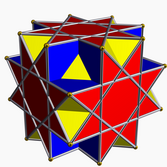

Uniform polyhedra and their duals

editUniform polyhedra are vertex-transitive and every face is a regular polygon. They may be subdivided into the regular, quasi-regular, or semi-regular, and may be convex or starry.

The duals of the uniform polyhedra have irregular faces but are face-transitive, and every vertex figure is a regular polygon. A uniform polyhedron has the same symmetry orbits as its dual, with the faces and vertices simply swapped over. The duals of the convex Archimedean polyhedra are sometimes called the Catalan solids.

The uniform polyhedra and their duals are traditionally classified according to their degree of symmetry, and whether they are convex or not.

| Convex uniform | Convex uniform dual | Star uniform | Star uniform dual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regular | Platonic solids | Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra | ||

| Quasiregular | Archimedean solids | Catalan solids | Uniform star polyhedron | |

| Semiregular | ||||

| Prisms | Bipyramids | Star prisms | Star bipyramids | |

| Antiprisms | Trapezohedra | Star antiprisms | Star trapezohedra | |

Isohedra

editAn isohedron is a polyhedron with symmetries acting transitively on its faces. Their topology can be represented by a face configuration. All 5 Platonic solids and 13 Catalan solids are isohedra, as well as the infinite families of trapezohedra and bipyramids. Some definitions of isohedra allow geometric variations including concave and self-intersecting forms.

Symmetry groups

editMany of the symmetries or point groups in three dimensions are named after polyhedra having the associated symmetry. These include:

- T – chiral tetrahedral symmetry; the rotation group for a regular tetrahedron; order 12.

- Td – full tetrahedral symmetry; the symmetry group for a regular tetrahedron; order 24.

- Th – pyritohedral symmetry; the symmetry of a pyritohedron; order 24.

- O – chiral octahedral symmetry;the rotation group of the cube and octahedron; order 24.

- Oh – full octahedral symmetry; the symmetry group of the cube and octahedron; order 48.

- I – chiral icosahedral symmetry; the rotation group of the icosahedron and the dodecahedron; order 60.

- Ih – full icosahedral symmetry; the symmetry group of the icosahedron and the dodecahedron; order 120.

- Cnv – n-fold pyramidal symmetry

- Dnh – n-fold prismatic symmetry

- Dnv – n-fold antiprismatic symmetry.

Those with chiral symmetry do not have reflection symmetry and hence have two enantiomorphous forms which are reflections of each other. Examples include the snub cuboctahedron and snub icosidodecahedron.

Other important families of polyhedra

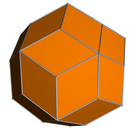

editZonohedra

editA zonohedron is a convex polyhedron in which every face is a polygon that is symmetric under rotations through 180°. Zonohedra can also be characterized as the Minkowski sums of line segments, and include several important space-filling polyhedra.[47]

Space-filling polyhedra

editA space-filling polyhedron packs with copies of itself to fill space. Such a close-packing or space-filling is often called a tessellation of space or a honeycomb. Space-filling polyhedra must have a Dehn invariant equal to zero. Some honeycombs involve more than one kind of polyhedron.

Lattice polyhedra

editA convex polyhedron in which all vertices have integer coordinates is called a lattice polyhedron or integral polyhedron. The Ehrhart polynomial of a lattice polyhedron counts how many points with integer coordinates lie within a scaled copy of the polyhedron, as a function of the scale factor. The study of these polynomials lies at the intersection of combinatorics and commutative algebra.[48] There is a far-reaching equivalence between lattice polyhedra and certain algebraic varieties called toric varieties.[49] This was used by Stanley to prove the Dehn–Sommerville equations for simplicial polytopes.[50]

Flexible polyhedra

editIt is possible for some polyhedra to change their overall shape, while keeping the shapes of their faces the same, by varying the angles of their edges. A polyhedron that can do this is called a flexible polyhedron. By Cauchy's rigidity theorem, flexible polyhedra must be non-convex. The volume of a flexible polyhedron must remain constant as it flexes; this result is known as the bellows theorem.[51]

Compounds

editA polyhedral compound is made of two or more polyhedra sharing a common centre. Symmetrical compounds often share the same vertices as other well-known polyhedra and may often also be formed by stellation. Some are listed in the list of Wenninger polyhedron models.

Orthogonal polyhedra

editAn orthogonal polyhedron is one all of whose edges are parallel to axes of a Cartesian coordinate system. This implies that all faces meet at right angles, but this condition is weaker: Jessen's icosahedron has faces meeting at right angles, but does not have axis-parallel edges.

Aside from the rectangular cuboids, orthogonal polyhedra are nonconvex. They are the 3D analogs of 2D orthogonal polygons, also known as rectilinear polygons. Orthogonal polyhedra are used in computational geometry, where their constrained structure has enabled advances on problems unsolved for arbitrary polyhedra, for example, unfolding the surface of a polyhedron to a polygonal net.[52]

Polycubes are a special case of orthogonal polyhedra that can be decomposed into identical cubes, and are three-dimensional analogues of planar polyominoes.[53]

Embedded regular maps with planar faces

editRegular maps are flag transitive abstract 2-manifolds and they have been studied already in the nineteenth century. In some cases they have geometric realizations. An example is the Szilassi polyhedron, a toroidal polyhedron that realizes the Heawood map. In this case, the polyhedron is much less symmetric than the underlying map, but in some cases it is possible for self-crossing polyhedra to realize some or all of the symmetries of a regular map.

Generalisations

editThe name 'polyhedron' has come to be used for a variety of objects having similar structural properties to traditional polyhedra.

Apeirohedra

editA classical polyhedral surface has a finite number of faces, joined in pairs along edges. The apeirohedra form a related class of objects with infinitely many faces. Examples of apeirohedra include:

- tilings or tessellations of the plane, and

- sponge-like structures called infinite skew polyhedra.

Complex polyhedra

editThere are objects called complex polyhedra, for which the underlying space is a complex Hilbert space rather than real Euclidean space. Precise definitions exist only for the regular complex polyhedra, whose symmetry groups are complex reflection groups. The complex polyhedra are mathematically more closely related to configurations than to real polyhedra.[54]

Curved polyhedra

editSome fields of study allow polyhedra to have curved faces and edges. Curved faces can allow digonal faces to exist with a positive area.

Spherical polyhedra

editWhen the surface of a sphere is divided by finitely many great arcs (equivalently, by planes passing through the center of the sphere), the result is called a spherical polyhedron. Many convex polytopes having some degree of symmetry (for example, all the Platonic solids) can be projected onto the surface of a concentric sphere to produce a spherical polyhedron. However, the reverse process is not always possible; some spherical polyhedra (such as the hosohedra) have no flat-faced analogue.[55]

Curved spacefilling polyhedra

editIf faces are allowed to be concave as well as convex, adjacent faces may be made to meet together with no gap. Some of these curved polyhedra can pack together to fill space. Two important types are:

- Bubbles in froths and foams, such as Weaire-Phelan bubbles.[56]

- Forms used in architecture.[57]

Ideal polyhedra

editConvex polyhedra can be defined in three-dimensional hyperbolic space in the same way as in Euclidean space, as the convex hulls of finite sets of points. However, in hyperbolic space, it is also possible to consider ideal points as well as the points that lie within the space. An ideal polyhedron is the convex hull of a finite set of ideal points. Its faces are ideal polygons, but its edges are defined by entire hyperbolic lines rather than line segments, and its vertices (the ideal points of which it is the convex hull) do not lie within the hyperbolic space.

Skeletons and polyhedra as graphs

editBy forgetting the face structure, any polyhedron gives rise to a graph, called its skeleton, with corresponding vertices and edges. Such figures have a long history: Leonardo da Vinci devised frame models of the regular solids, which he drew for Pacioli's book Divina Proportione, and similar wire-frame polyhedra appear in M.C. Escher's print Stars.[58] One highlight of this approach is Steinitz's theorem, which gives a purely graph-theoretic characterization of the skeletons of convex polyhedra: it states that the skeleton of every convex polyhedron is a 3-connected planar graph, and every 3-connected planar graph is the skeleton of some convex polyhedron.

An early idea of abstract polyhedra was developed in Branko Grünbaum's study of "hollow-faced polyhedra." Grünbaum defined faces to be cyclically ordered sets of vertices, and allowed them to be skew as well as planar.[2]

The graph perspective allows one to apply graph terminology and properties to polyhedra. For example, the tetrahedron and Császár polyhedron are the only known polyhedra whose skeletons are complete graphs (K4), and various symmetry restrictions on polyhedra give rise to skeletons that are symmetric graphs.

Alternative usages

editFrom the latter half of the twentieth century, various mathematical constructs have been found to have properties also present in traditional polyhedra. Rather than confining the term "polyhedron" to describe a three-dimensional polytope, it has been adopted to describe various related but distinct kinds of structure.

Higher-dimensional polyhedra

editA polyhedron has been defined as a set of points in real affine (or Euclidean) space of any dimension n that has flat sides. It may alternatively be defined as the intersection of finitely many half-spaces. Unlike a conventional polyhedron, it may be bounded or unbounded. In this meaning, a polytope is a bounded polyhedron.[14][15]

Analytically, such a convex polyhedron is expressed as the solution set for a system of linear inequalities. Defining polyhedra in this way provides a geometric perspective for problems in linear programming.[59]: 9

Topological polyhedra

editA topological polytope is a topological space given along with a specific decomposition into shapes that are topologically equivalent to convex polytopes and that are attached to each other in a regular way.

Such a figure is called simplicial if each of its regions is a simplex, i.e. in an n-dimensional space each region has n+1 vertices. The dual of a simplicial polytope is called simple. Similarly, a widely studied class of polytopes (polyhedra) is that of cubical polyhedra, when the basic building block is an n-dimensional cube.

Abstract polyhedra

editAn abstract polytope is a partially ordered set (poset) of elements whose partial ordering obeys certain rules of incidence (connectivity) and ranking. The elements of the set correspond to the vertices, edges, faces and so on of the polytope: vertices have rank 0, edges rank 1, etc. with the partially ordered ranking corresponding to the dimensionality of the geometric elements. The empty set, required by set theory, has a rank of −1 and is sometimes said to correspond to the null polytope. An abstract polyhedron is an abstract polytope having the following ranking:

- rank 3: The maximal element, sometimes identified with the body.

- rank 2: The polygonal faces.

- rank 1: The edges.

- rank 0: the vertices.

- rank −1: The empty set, sometimes identified with the null polytope or nullitope.[60]

Any geometric polyhedron is then said to be a "realization" in real space of the abstract poset as described above.

History

editBefore the Greeks

editPolyhedra appeared in early architectural forms such as cubes and cuboids, with the earliest four-sided Egyptian pyramids dating from the 27th century BC.[61] The Moscow Mathematical Papyrus from approximately 1800–1650 BC includes an early written study of polyhedra and their volumes (specifically, the volume of a frustum).[62] The mathematics of the Old Babylonian Empire, from roughly the same time period as the Moscow Papyrus, also included calculations of the volumes of cuboids (and of non-polyhedral cylinders), and calculations of the height of such a shape needed to attain a given volume.[63]

The Etruscans preceded the Greeks in their awareness of at least some of the regular polyhedra, as evidenced by the discovery of an Etruscan dodecahedron made of soapstone on Monte Loffa. Its faces were marked with different designs, suggesting to some scholars that it may have been used as a gaming die.[64]

Ancient Greece

editAncient Greek mathematicians discovered and studied the convex regular polyhedra, which came to be known as the Platonic solids. Their first written description is in the Timaeus of Plato (circa 360 BC), which associates four of them with the four elements and the fifth to the overall shape of the universe. A more mathematical treatment of these five polyhedra was written soon after in the Elements of Euclid. An early commentator on Euclid (possibly Geminus) writes that the attribution of these shapes to Plato is incorrect: Pythagoras knew the tetrahedron, cube, and dodecahedron, and Theaetetus (circa 417 BC) discovered the other two, the octahedron and icosahedron.[65] Later, Archimedes expanded his study to the convex uniform polyhedra which now bear his name. His original work is lost and his solids come down to us through Pappus.[66]

Ancient China

editBoth cubical dice and 14-sided dice in the shape of a truncated octahedron in China have been dated back as early as the Warring States period.[67]

By 236 AD, Liu Hui was describing the dissection of the cube into its characteristic tetrahedron (orthoscheme) and related solids, using assemblages of these solids as the basis for calculating volumes of earth to be moved during engineering excavations.[68]

Medieval Islam

editAfter the end of the Classical era, scholars in the Islamic civilisation continued to take the Greek knowledge forward (see Mathematics in medieval Islam).[69] The 9th century scholar Thabit ibn Qurra included the calculation of volumes in his studies,[70] and wrote a work on the cuboctahedron. Then in the 10th century Abu'l Wafa described the convex regular and quasiregular spherical polyhedra.[71]

Renaissance

editAs with other areas of Greek thought maintained and enhanced by Islamic scholars, Western interest in polyhedra revived during the Italian Renaissance. Artists constructed skeletal polyhedra, depicting them from life as a part of their investigations into perspective.[73] Toroidal polyhedra, made of wood and used to support headgear, became a common exercise in perspective drawing, and were depicted in marquetry panels of the period as a symbol of geometry.[74] Piero della Francesca wrote about constructing perspective views of polyhedra, and rediscovered many of the Archimedean solids. Leonardo da Vinci illustrated skeletal models of several polyhedra for a book by Luca Pacioli,[75] with text largely plagiarized from della Francesca.[76] Polyhedral nets make an appearance in the work of Albrecht Dürer.[77]

Several works from this time investigate star polyhedra, and other elaborations of the basic Platonic forms. A marble tarsia in the floor of St. Mark's Basilica, Venice, designed by Paolo Uccello, depicts a stellated dodecahedron.[78] As the Renaissance spread beyond Italy, later artists such as Wenzel Jamnitzer, Dürer and others also depicted polyhedra of increasing complexity, many of them novel, in imaginative etchings.[73] Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) used star polygons, typically pentagrams, to build star polyhedra. Some of these figures may have been discovered before Kepler's time, but he was the first to recognize that they could be considered "regular" if one removed the restriction that regular polyhedra must be convex.[79]

In the same period, Euler's polyhedral formula, a linear equation relating the numbers of vertices, edges, and faces of a polyhedron, was stated for the Platonic solids in 1537 in an unpublished manuscript by Francesco Maurolico.[80]

17th–19th centuries

editRené Descartes, in around 1630, wrote his book De solidorum elementis studying convex polyhedra as a general concept, not limited to the Platonic solids and their elaborations. The work was lost, and not rediscovered until the 19th century. One of its contributions was Descartes' theorem on total angular defect, which is closely related to Euler's polyhedral formula.[81] Leonhard Euler, for whom the formula is named, introduced it in 1758 for convex polyhedra more generally, albeit with an incorrect proof.[82] Euler's work (together with his earlier solution to the puzzle of the Seven Bridges of Königsberg) became the foundation of the new field of topology.[83] The core concepts of this field, including generalizations of the polyhedral formula, were developed in the late nineteenth century by Henri Poincaré, Enrico Betti, Bernhard Riemann, and others.[84]

In the early 19th century, Louis Poinsot extended Kepler's work, and discovered the remaining two regular star polyhedra. Soon after, Augustin-Louis Cauchy proved Poinsot's list complete, subject to an unstated assumption that the sequence of vertices and edges of each polygonal side cannot admit repetitions (an assumption that had been considered but rejected in the earlier work of A. F. L. Meister).[85] They became known as the Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra, and their usual names were given by Arthur Cayley.[86] Meanwhile, the discovery of higher dimensions in the early 19th century led Ludwig Schläfli by 1853 to the idea of higher-dimensional polytopes.[87] Additionally, in the late 19th century, Russian crystallographer Evgraf Fedorov completed the classification of parallelohedra, convex polyhedra that tile space by translations.[88]

20th–21st centuries

editMathematics in the 20th century dawned with Hilbert's problems, one of which, Hilbert's third problem, concerned polyhedra and their dissections. It was quickly solved by Hilbert's student Max Dehn, introducing the Dehn invariant of polyhedra.[89] Steinitz's theorem, published by Ernst Steinitz in 1992, characterized the graphs of convex polyhedra, bringing modern ideas from graph theory and combinatorics into the study of polyhedra.[90]

The Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra may be constructed from the Platonic solids by a process called stellation. Most stellations are not regular. The study of stellations of the Platonic solids was given a big push by H.S.M. Coxeter and others in 1938, with the now famous paper The 59 icosahedra.[91] Coxeter's analysis signalled a rebirth of interest in geometry. Coxeter himself went on to enumerate the star uniform polyhedra for the first time, to treat tilings of the plane as polyhedra, to discover the regular skew polyhedra and to develop the theory of complex polyhedra first discovered by Shephard in 1952, as well as making fundamental contributions to many other areas of geometry.[92]

In the second part of the twentieth century, both Branko Grünbaum and Imre Lakatos pointed out the tendency among mathematicians to define a "polyhedron" in different and sometimes incompatible ways to suit the needs of the moment.[1][2] In a series of papers, Grünbaum broadened the accepted definition of a polyhedron, discovering many new regular polyhedra. At the close of the 20th century these latter ideas merged with other work on incidence complexes to create the modern idea of an abstract polyhedron (as an abstract 3-polytope), notably presented by McMullen and Schulte.[93]

Polyhedra make a frequent appearance in modern computational geometry, computer graphics, and geometric design with topics including the reconstruction of polyhedral surfaces or surface meshes from scattered data points,[94] geodesics on polyhedral surfaces,[95] visibility and illumination in polyhedral scenes,[96] polycubes and other non-convex polyhedra with axis-parallel sides,[97] algorithmic forms of Steinitz's theorem,[98] and the still-unsolved problem of the existence of polyhedral nets for convex polyhedra.[99]

In nature

editFor natural occurrences of regular polyhedra, see Regular polyhedron § Regular polyhedra in nature.

Irregular polyhedra appear in nature as crystals.

See also

edit- Extension of a polyhedron

- Goldberg polyhedron

- List of books about polyhedra

- List of convex regular-faced polyhedra

- List of small polyhedra by vertex count

- Near-miss Johnson solid

- Polyhedron model

- Polyhedral combinatorics

- Polyhedral group

- Polyhedral number

- Polyhedral skeletal electron pair theory

- Polyhedral space

- Polyhedral symbol

- Polyhedral terrain

- Polytope model

- Schlegel diagram

- Lists of shapes

- Stella (software)

Notes

edit- ^ The Archimedean solids once had fourteenth solid known as pseudorhombicuboctahedron, mistakenly constructing rhombicuboctahedron. However, it was debarred for having no vertex-transitive property, which included it to the Johnson solid instead.[20]

References

edit- ^ a b Lakatos, Imre (2015) [1976], Worrall, John; Zahar, Elie (eds.), Proofs and Refutations: The logic of mathematical discovery, Cambridge Philosophy Classics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 16, doi:10.1017/CBO9781316286425, ISBN 978-1-107-53405-6, MR 3469698,

definitions are frequently proposed and argued about

. - ^ a b c Grünbaum, Branko (1994), "Polyhedra with hollow faces", in Bisztriczky, Tibor; McMullen, Peter; Schneider, Rolf; Weiss, A. (eds.), Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Study Institute on Polytopes: Abstract, Convex and Computational, Dordrecht: Kluwer Acad. Publ., pp. 43–70, doi:10.1007/978-94-011-0924-6_3, ISBN 978-94-010-4398-4, MR 1322057; for quote, see p. 43.

- ^ Loeb, Arthur L. (2013), "Polyhedra: Surfaces or solids?", in Senechal, Marjorie (ed.), Shaping Space: Exploring Polyhedra in Nature, Art, and the Geometrical Imagination (2nd ed.), Springer, pp. 65–75, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-92714-5_5, ISBN 978-0-387-92713-8

- ^ McCormack, Joseph P. (1931), Solid Geometry, D. Appleton-Century Company, p. 416.

- ^ de Berg, M.; van Kreveld, M.; Overmars, M.; Schwarzkopf, O. (2000), Computational Geometry: Algorithms and Applications (2nd ed.), Springer, p. 64.

- ^ Matveev, S.V. (2001) [1994], "Polyhedron, abstract", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- ^ Stewart, B. M. (1980), Adventures Among the Toroids: A study of orientable polyhedra with regular faces (2nd ed.), p. 6.

- ^ a b c Cromwell, Peter R. (1997), Polyhedra, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55432-9, MR 1458063; for definitions of polyhedra, see pp. 206–209; for polyhedra with equal regular faces, see p. 86.

- ^ O'Rourke, Joseph (1993), "Computational Geometry in C" (PDF), Computers in Physics, 9 (1): 113–116, Bibcode:1995ComPh...9...55O, doi:10.1063/1.4823371.

- ^ a b Grünbaum, Branko (1999), "Acoptic polyhedra" (PDF), Advances in discrete and computational geometry (South Hadley, MA, 1996), Contemporary Mathematics, vol. 223, Providence, Rhode Island: American Mathematical Society, pp. 163–199, doi:10.1090/conm/223/03137, ISBN 978-0-8218-0674-6, MR 1661382, archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-30, retrieved 2022-07-01.

- ^ Bokowski, J.; Guedes de Oliveira, A. (2000), "On the generation of oriented matroids", Discrete and Computational Geometry, 24 (2–3): 197–208, doi:10.1007/s004540010027, MR 1756651.

- ^ a b Burgiel, H.; Stanton, D. (2000), "Realizations of regular abstract polyhedra of types {3,6} and {6,3}", Discrete and Computational Geometry, 24 (2–3): 241–255, doi:10.1007/s004540010030, MR 1758047.

- ^ a b Grünbaum, Branko (2003), "Are your polyhedra the same as my polyhedra?" (PDF), in Aronov, Boris; Basu, Saugata; Pach, János; Sharir, Micha (eds.), Discrete and Computational Geometry: The Goodman–Pollack Festschrift, Algorithms and Combinatorics, vol. 25, Berlin: Springer, pp. 461–488, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.102.755, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55566-4_21, ISBN 978-3-642-62442-1, MR 2038487

- ^ a b c Grünbaum, Branko (2003), Convex Polytopes, Graduate Texts in Mathematics, vol. 221 (2nd ed.), New York: Springer-Verlag, p. 26, doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0019-9, ISBN 978-0-387-00424-2, MR 1976856.

- ^ a b c Bruns, Winfried; Gubeladze, Joseph (2009), "Definition 1.1", Polytopes, Rings, and K-theory, Springer Monographs in Mathematics, Dordrecht: Springer, p. 5, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.2630, doi:10.1007/b105283, ISBN 978-0-387-76355-2, MR 2508056.

- ^ Boissonnat, J. D.; Yvinec, M. (June 1989), Probing a scene of non convex polyhedra, Proceedings of the fifth annual symposium on Computational geometry, pp. 237–246, doi:10.1145/73833.73860.

- ^ Litchenberg, D. R. (1988), "Pyramids, Prisms, Antiprisms, and Deltahedra", The Mathematics Teacher, 81 (4): 261–265, JSTOR 27965792.

- ^ Kern, William F.; Bland, James R. (1938), Solid Mensuration with proofs, p. 75.

- ^ Cromwell (1997), p. 51–52.

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (2009), "An enduring error" (PDF), Elemente der Mathematik, 64 (3): 89–101, doi:10.4171/EM/120, MR 2520469. Reprinted in Pitici, Mircea, ed. (2011), The Best Writing on Mathematics 2010, Princeton University Press, pp. 18–31.

- ^ Diudea, M. V. (2018), Multi-shell Polyhedral Clusters, Springer, p. 39, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64123-2, ISBN 978-3-319-64123-2.

- ^ Cundy, H. Martyn (1952), "Deltahedra", Mathematical Gazette, 36: 263–266, doi:10.2307/3608204, JSTOR 3608204.

- ^ Berman, Martin (1971), "Regular-faced convex polyhedra", Journal of the Franklin Institute, 291 (5): 329–352, doi:10.1016/0016-0032(71)90071-8, MR 0290245.

- ^ Hartshorne (2000), p. 464.

- ^ Timofeenko, A. V. (2010), "Junction of Non-composite Polyhedra" (PDF), St. Petersburg Mathematical Journal, 21 (3): 483–512, doi:10.1090/S1061-0022-10-01105-2.

- ^ Schramm, Oded (1992-12-01), "How to cage an egg", Inventiones Mathematicae, 107 (1): 543–560, Bibcode:1992InMat.107..543S, doi:10.1007/BF01231901, ISSN 1432-1297.

- ^ a b Bridge, N.J. (1974), "Facetting the dodecahedron", Acta Crystallographica, A30 (4): 548–552, Bibcode:1974AcCrA..30..548B, doi:10.1107/S0567739474001306.

- ^ Inchbald, G. (2006), "Facetting diagrams", The Mathematical Gazette, 90 (518): 253–261, doi:10.1017/S0025557200179653, S2CID 233358800.

- ^ Peirce, Charles S. (1976), Eisele, Carolyn (ed.), The New Elements of Mathematics, Volume II: Algebra and Geometry, Mouton Publishers & Humanities Press, p. 297, ISBN 9783110818840

- ^ O'Keefe, Michael; Hyde, Bruce G. (2020) [1996], Crystal Structures: Patterns and Symmetry, Dover Publications, p. 134, ISBN 9780486836546

- ^ a b c Ringel, Gerhard (1974), "Classification of surfaces", Map Color Theorem, Springer, pp. 34–53, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-65759-7_3, ISBN 978-3-642-65761-0

- ^ Richeson, David S. (2008), Euler's Gem: The polyhedron formula and the birth of topology, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-12677-7, MR 2440945, pp. 157, 180.

- ^ Stewart, B. M. (1980), Adventures Among the Toroids: A Study of Orientable Polyhedra with Regular Faces (2nd ed.), B. M. Stewart, ISBN 978-0-686-11936-4.

- ^ Cundy, H. Martyn; Rollett, A.P. (1961), "3.2 Duality", Mathematical models (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, pp. 78–79, MR 0124167.

- ^ Grünbaum, B.; Shephard, G.C. (1969), "Convex polytopes" (PDF), Bulletin of the London Mathematical Society, 1 (3): 257–300, doi:10.1112/blms/1.3.257, MR 0250188, archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-22, retrieved 2017-02-21. See in particular the bottom of page 260.

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (1947), Regular Polytopes, Methuen, p. 16

- ^ Barnette, David (1973), "A proof of the lower bound conjecture for convex polytopes", Pacific Journal of Mathematics, 46 (2): 349–354, doi:10.2140/pjm.1973.46.349, MR 0328773

- ^ Luotoniemi, Taneli (2017), "Crooked houses: Visualizing the polychora with hyperbolic patchwork", in Swart, David; Séquin, Carlo H.; Fenyvesi, Kristóf (eds.), Proceedings of Bridges 2017: Mathematics, Art, Music, Architecture, Education, Culture, Phoenix, Arizona: Tessellations Publishing, pp. 17–24, ISBN 978-1-938664-22-9

- ^ Coxeter, H. S. M. (January 1930), "The polytopes with regular-prismatic vertex figures", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A, 229 (670–680), The Royal Society: 329–425, Bibcode:1930RSPTA.229..329C, doi:10.1098/rsta.1930.0009

- ^ Hartshorne, Robin (2000), "Example 44.2.3, the "punched-in icosahedron"", Geometry: Euclid and beyond, Undergraduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer-Verlag, New York, p. 442, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-22676-7, ISBN 0-387-98650-2, MR 1761093

- ^ Goldman, Ronald N. (1991), "Chapter IV.1: Area of planar polygons and volume of polyhedra", in Arvo, James (ed.), Graphic Gems Package: Graphics Gems II, Academic Press, pp. 170–171

- ^ Büeler, B.; Enge, A.; Fukuda, K. (2000), "Exact Volume Computation for Polytopes: A Practical Study", Polytopes — Combinatorics and Computation, pp. 131–154, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.39.7700, doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-8438-9_6, ISBN 978-3-7643-6351-2

- ^ Sydler, J.-P. (1965), "Conditions nécessaires et suffisantes pour l'équivalence des polyèdres de l'espace euclidien à trois dimensions", Comment. Math. Helv. (in French), 40: 43–80, doi:10.1007/bf02564364, MR 0192407, S2CID 123317371

- ^ Hazewinkel, M. (2001) [1994], "Dehn invariant", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

- ^ Debrunner, Hans E. (1980), "Über Zerlegungsgleichheit von Pflasterpolyedern mit Würfeln", Archiv der Mathematik (in German), 35 (6): 583–587, doi:10.1007/BF01235384, MR 0604258, S2CID 121301319.

- ^ Alexandrov, Victor (2010), "The Dehn invariants of the Bricard octahedra", Journal of Geometry, 99 (1–2): 1–13, arXiv:0901.2989, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.243.7674, doi:10.1007/s00022-011-0061-7, MR 2823098, S2CID 17515249.

- ^ Taylor, Jean E. (1992), "Zonohedra and generalized zonohedra", American Mathematical Monthly, 99 (2): 108–111, doi:10.2307/2324178, JSTOR 2324178, MR 1144350.

- ^ Stanley, Richard P. (1997), Enumerative Combinatorics, Volume I (1 ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 235–239, ISBN 978-0-521-66351-9

- ^ Cox, David A. (2011), Toric varieties, John B. Little, Henry K. Schenck, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-0-8218-4819-7, OCLC 698027255

- ^ Stanley, Richard P. (1996), Combinatorics and commutative algebra (2nd ed.), Boston: Birkhäuser, ISBN 0-8176-3836-9, OCLC 33080168

- ^ Demaine, Erik D.; O'Rourke, Joseph (2007), "23.2 Flexible polyhedra", Geometric Folding Algorithms: Linkages, origami, polyhedra, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 345–348, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511735172, ISBN 978-0-521-85757-4, MR 2354878.

- ^ O'Rourke, Joseph (2008), "Unfolding orthogonal polyhedra", Surveys on discrete and computational geometry, Contemp. Math., vol. 453, Amer. Math. Soc., Providence, RI, pp. 307–317, doi:10.1090/conm/453/08805, ISBN 978-0-8218-4239-3, MR 2405687.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (November 1966), "Mathematical Games: Is it possible to visualize a four-dimensional figure?", Scientific American, 215 (5): 138–143, doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1166-138, JSTOR 24931332

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M. (1974), Regular Complex Polytopes, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, MR 0370328. [page needed]

- ^ Popko, Edward S. (2012), Divided Spheres: Geodesics and the Orderly Subdivision of the Sphere, CRC Press, p. 463, ISBN 978-1-4665-0430-1,

A hosohedron is only possible on a sphere

. - ^ Kraynik, A.M.; Reinelt, D.A. (2007), "Foams, Microrheology of", in Mortensen, Andreas (ed.), Concise Encyclopedia of Composite Materials (2nd ed.), Elsevier, pp. 402–407. See in particular p. 403: "foams consist of polyhedral gas bubbles ... each face on a polyhedron is a minimal surface with uniform mean curvature ... no face can be a flat polygon with straight edges".

- ^ Pearce, P. (1978), "14 Saddle polyhedra and continuous surfaces as environmental structures", Structure in nature is a strategy for design, MIT Press, p. 224, ISBN 978-0-262-66045-7.

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M. (1985), "A special book review: M.C. Escher: His life and complete graphic work", The Mathematical Intelligencer, 7 (1): 59–69, doi:10.1007/BF03023010, S2CID 189887063 Coxeter's analysis of Stars is on pp. 61–62.

- ^ Grötschel, Martin; Lovász, László; Schrijver, Alexander (1993), Geometric algorithms and combinatorial optimization, Algorithms and Combinatorics, vol. 2 (2nd ed.), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-78240-4, ISBN 978-3-642-78242-8, MR 1261419

- ^ N.W. Johnson: Geometries and Transformations, (2018) ISBN 978-1-107-10340-5 Chapter 11: Finite Symmetry Groups, 11.1 Polytopes and Honeycombs, p.224

- ^ Kitchen, K. A. (October 1991), "The chronology of ancient Egypt", World Archaeology, 23 (2): 201–208, doi:10.1080/00438243.1991.9980172

- ^ Gunn, Battiscombe; Peet, T. Eric (May 1929), "Four Geometrical Problems from the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus", The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 15 (1): 167–185, doi:10.1177/030751332901500130, S2CID 192278129

- ^ Friberg, Jöran (2000), "Mathematics at Ur in the Old Babylonian Period", Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale, 94 (2): 97–188, JSTOR 23281940

- ^ Sparavigna, Amelia Carolina (2012), An Etruscan dodecahedron, arXiv:1205.0706

- ^ Eves, Howard (January 1969), "A geometry capsule concerning the five platonic solids", Historically Speaking, The Mathematics Teacher, 62 (1): 42–44, doi:10.5951/mt.62.1.0042, JSTOR 27958041

- ^ Field, J. V. (1997), "Rediscovering the Archimedean polyhedra: Piero della Francesca, Luca Pacioli, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Daniele Barbaro, and Johannes Kepler", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 50 (3–4): 241–289, doi:10.1007/BF00374595, JSTOR 41134110, MR 1457069, S2CID 118516740

- ^ Bréard, Andrea; Cook, Constance A. (December 2019), "Cracking bones and numbers: solving the enigma of numerical sequences on ancient Chinese artifacts", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 74 (4): 313–343, doi:10.1007/s00407-019-00245-9, S2CID 253898304

- ^ van der Waerden, B. L. (1983), "Chapter 7: Liu Hui and Aryabhata", Geometry and Algebra in Ancient Civilizations, Springer, pp. 192–217, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-61779-9_7

- ^ Knorr, Wilbur (1983), "On the transmission of geometry from Greek into Arabic", Historia Mathematica, 10 (1): 71–78, doi:10.1016/0315-0860(83)90034-4, MR 0698139

- ^ Rashed, Roshdi (2009), "Thābit ibn Qurra et l'art de la mesure", in Rashed, Roshdi (ed.), Thābit ibn Qurra: Science and Philosophy in Ninth-Century Baghdad, Scientia Graeco-Arabica (in French), vol. 4, Walter de Gruyter, pp. 173–175, ISBN 9783110220780

- ^ Hisarligil, Hakan; Hisarligil, Beyhan Bolak (December 2017), "The geometry of cuboctahedra in medieval art in Anatolia", Nexus Network Journal, 20 (1): 125–152, doi:10.1007/s00004-017-0363-7

- ^ Gamba, Enrico (2012), "The mathematical ideas of Luca Pacioli depicted by Iacopo de' Barbari in the Doppio ritratto", in Emmer, Michele (ed.), Imagine Math, Springer, pp. 267–271, doi:10.1007/978-88-470-2427-4_25, ISBN 978-88-470-2427-4

- ^ a b Andrews, Noam (2022), The Polyhedrists: Art and Geometry in the Long Sixteenth Century, MIT Press, ISBN 9780262046640

- ^ Calvo-López, José; Alonso-Rodríguez, Miguel Ángel (February 2010), "Perspective versus stereotomy: From Quattrocento polyhedral rings to sixteenth-century Spanish torus vaults", Nexus Network Journal, 12 (1): 75–111, doi:10.1007/s00004-010-0018-4

- ^ Field, J. V. (1997), "Rediscovering the Archimedean polyhedra: Piero della Francesca, Luca Pacioli, Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Daniele Barbaro, and Johannes Kepler", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 50 (3–4): 241–289, doi:10.1007/BF00374595, JSTOR 41134110, MR 1457069, S2CID 118516740

- ^ Montebelli, Vico (2015), "Luca Pacioli and perspective (part I)", Lettera Matematica, 3 (3): 135–141, doi:10.1007/s40329-015-0090-4, MR 3402538, S2CID 193533200

- ^ Ghomi, Mohammad (2018), "Dürer's unfolding problem for convex polyhedra" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 65 (1): 25–27, doi:10.1090/noti1609, MR 3726673

- ^ Saffaro, Lucio (1992), "Cosmoids, fullerenes and continuous polygons", in Taliani, C.; Ruani, G.; Zamboni, R. (eds.), Fullerenes: Status and Perspectives, Proceedings of the 1st Italian Workshop, Bologna, Italy, 6–7 February, Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 55–64

- ^ Field, J. V. (1979), "Kepler's star polyhedra", Vistas in Astronomy, 23 (2): 109–141, Bibcode:1979VA.....23..109F, doi:10.1016/0083-6656(79)90001-1, MR 0546797

- ^ Friedman, Michael (2018), A History of Folding in Mathematics: Mathematizing the Margins, Science Networks. Historical Studies, vol. 59, Birkhäuser, p. 71, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-72487-4, ISBN 978-3-319-72486-7

- ^ Federico, Pasquale Joseph (1982), Descartes on Polyhedra: A Study of the "De solidorum elementis", Sources in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences, vol. 4, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90760-2, MR 0680214

- ^ Francese, Christopher; Richeson, David (2007), "The flaw in Euler's proof of his polyhedral formula", The American Mathematical Monthly, 114 (4): 286–296, doi:10.1080/00029890.2007.11920417, MR 2281926, S2CID 10023787

- ^ Alexanderson, Gerald L. (2006), "About the cover: Euler and Königsberg's bridges: a historical view", American Mathematical Society, New Series, 43 (4): 567–573, doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-06-01130-X, MR 2247921

- ^ Eckmann, Beno (2006), "The Euler characteristic – a few highlights in its long history", Mathematical Survey Lectures 1943–2004, Springer, pp. 177–188, doi:10.1007/978-3-540-33791-1_15, ISBN 978-3-540-33791-1, MR 2269092

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (1994), "Regular polyhedra", in Grattan-Guinness, I. (ed.), Companion Encyclopedia of the History and Philosophy of the Mathematical Sciences, vol. 2, Routledge, pp. 866–876, ISBN 0-415-03785-9, MR 1469978

- ^ Malkevitch, Joseph (2018), "Regular-faced polyhedra: remembering Norman Johnson", AMS Feature column, American Mathematical Society, retrieved 2023-05-27

- ^ Coxeter (1947), pp. 141–143.

- ^ Austin, David (November 2013), "Fedorov's five parallelohedra", AMS Feature Column, American Mathematical Society

- ^ Zeeman, E. C. (July 2002), "On Hilbert's third problem", The Mathematical Gazette, 86 (506): 241–247, doi:10.2307/3621846, JSTOR 3621846, S2CID 125593771

- ^ Grünbaum, Branko (2007), "Graphs of polyhedra; polyhedra as graphs", Discrete Mathematics, 307 (3–5): 445–463, doi:10.1016/j.disc.2005.09.037, hdl:1773/2276, MR 2287486

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M.; Du Val, P.; Flather, H.T.; Petrie, J.F. (1999) [1938], The Fifty-Nine Icosahedra, Tarquin Publications, ISBN 978-1-899618-32-3, MR 0676126.

- ^ Roberts, Siobhan (2009), King of Infinite Space: Donald Coxeter, the Man Who Saved Geometry, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 9780802718327

- ^ McMullen, Peter; Schulte, Egon (2002), Abstract Regular Polytopes, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and its Applications, vol. 92, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Lim, Seng Poh; Haron, Habibollah (March 2012), "Surface reconstruction techniques: a review", Artificial Intelligence Review, 42 (1): 59–78, doi:10.1007/s10462-012-9329-z, S2CID 254232891

- ^ Mitchell, Joseph S. B.; Mount, David M.; Papadimitriou, Christos H. (1987), "The discrete geodesic problem", SIAM Journal on Computing, 16 (4): 647–668, doi:10.1137/0216045, MR 0899694

- ^ Teller, Seth J.; Hanrahan, Pat (1993), "Global visibility algorithms for illumination computations", in Whitton, Mary C. (ed.), Proceedings of the 20th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, SIGGRAPH 1993, Anaheim, CA, USA, August 2–6, 1993, Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 239–246, doi:10.1145/166117.166148, ISBN 0-89791-601-8, S2CID 7957200

- ^ Cherchi, Gianmarco (February 2019), Polycube Optimization and Applications: From the Digital World to Manufacturing (Doctoral dissertation), University of Cagliari, hdl:11584/261570

- ^ Rote, Günter (2011), "Realizing planar graphs as convex polytopes", in van Kreveld, Marc J.; Speckmann, Bettina (eds.), Graph Drawing – 19th International Symposium, GD 2011, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, September 21–23, 2011, Revised Selected Papers, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 7034, Springer, pp. 238–241, doi:10.1007/978-3-642-25878-7_23, ISBN 978-3-642-25877-0

- ^ Demaine, Erik; O'Rourke, Joseph (2007), Geometric Folding Algorithms: Linkages, Origami, Polyhedra, Cambridge University Press

External links

editGeneral theory

edit- Weisstein, Eric W., "Polyhedron", MathWorld

- Polyhedra Pages

- Uniform Solution for Uniform Polyhedra by Dr. Zvi Har'El Archived 2015-11-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Symmetry, Crystals and Polyhedra

Lists and databases of polyhedra

edit- Virtual Reality Polyhedra – The Encyclopedia of Polyhedra.

- Electronic Geometry Models – Contains a peer reviewed selection of polyhedra with unusual properties.

- Polyhedron Models – Virtual polyhedra.

- Paper Models of Uniform (and other) Polyhedra

Free software

edit- A Plethora of Polyhedra – An interactive and free collection of polyhedra in Java. Features includes nets, planar sections, duals, truncations and stellations of more than 300 polyhedra.

- Hyperspace Star Polytope Slicer – Explorer java applet, includes a variety of 3d viewer options.

- openSCAD – Free cross-platform software for programmers. Polyhedra are just one of the things you can model. The openSCAD User Manual is also available.

- OpenVolumeMesh – An open source cross-platform C++ library for handling polyhedral meshes. Developed by the Aachen Computer Graphics Group, RWTH Aachen University.

- Polyhedronisme Archived 2012-04-25 at the Wayback Machine – Web-based tool for generating polyhedra models using Conway Polyhedron Notation. Models can be exported as 2D PNG images, or as 3D OBJ or VRML2 files.

Resources for making physical models

edit- Paper Models of Polyhedra Free nets of polyhedra.

- Simple instructions for building over 30 paper polyhedra

- Polyhedra plaited with paper strips – Polyhedra models constructed without use of glue.