Richard John Santorum (/sænˈtɔːrəm/ san-TOR-əm; born May 10, 1958) is an American politician, attorney, author, and political commentator who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate from 1995 to 2007. He was the Senate's third-ranking Republican during the final six years of his tenure. He also ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States in the 2012 Republican primaries, finishing second to Mitt Romney.

Rick Santorum | |

|---|---|

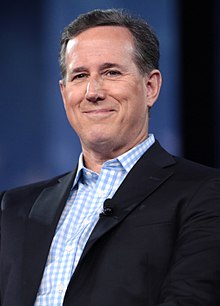

Santorum in 2017 | |

| Chair of the Senate Republican Conference | |

| In office January 3, 2001 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Leader | Trent Lott Bill Frist |

| Preceded by | Connie Mack III |

| Succeeded by | Jon Kyl |

| United States Senator from Pennsylvania | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 3, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Harris Wofford |

| Succeeded by | Bob Casey Jr. |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania's 18th district | |

| In office January 3, 1991 – January 3, 1995 | |

| Preceded by | Doug Walgren |

| Succeeded by | Mike Doyle |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Richard John Santorum May 10, 1958 Winchester, Virginia, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Karen Garver (m. 1990) |

| Children | 8 |

| Education | Pennsylvania State University (BA) University of Pittsburgh (MBA) Dickinson School of Law (JD) |

| Signature | |

| Website | www |

Santorum was elected to the United States Senate from Pennsylvania in 1994. He served two terms until losing his 2006 reelection bid. A Roman Catholic, Santorum is a social conservative who opposes abortion and same-sex marriage and embraced a cultural warrior image during his Senate tenure. While serving as a senator, Santorum authored the Santorum Amendment, which would have promoted the teaching of intelligent design. He was a leading sponsor of the 2003 federal law known as the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act.

In the years following his departure from the Senate, Santorum has worked as a consultant, private practice lawyer, and news contributor. He ran for the Republican nomination in the 2012 U.S. presidential election. Before suspending his campaign on April 10, 2012, Santorum exceeded expectations by winning 11 primaries and caucuses and receiving nearly four million votes, making him the runner-up to eventual nominee Mitt Romney. Santorum ran for president again in 2016, but ended his campaign in February 2016 after a poor showing in the Iowa caucuses. In January 2017, he became a CNN senior political commentator. However, he was terminated from his contract with CNN in May 2021 due to comments he made about Native Americans a few weeks prior which were deemed "dismissive".[1]

Early life and education

editRichard John Santorum was born in Winchester, Virginia.[2] He is the second of the three children of Aldo Santorum (1923–2011), a clinical psychologist who immigrated to the United States at age seven from Riva, Trentino, Italy,[3] and Catherine (Dughi) Santorum (1918–2019), an administrative nurse[3][4][5] who was of Italian and Irish ancestry.[6]

Santorum grew up in Berkeley County, West Virginia, and Butler County, Pennsylvania. In West Virginia, his family lived in an apartment provided by the Veterans Administration.[7] Santorum attended elementary school at Butler Catholic School and then went on to Butler Senior High School. He was nicknamed "Rooster", supposedly for both a cowlick strand of hair and an assertive nature, particularly on important political issues.[8][9][10][11] After his parents transferred to the Naval Station Great Lakes in northern Illinois, Santorum attended the Carmel High School in Mundelein, Illinois, for one year, graduating in 1976.[12]

Santorum attended Pennsylvania State University for his undergraduate studies, serving as chairman of the university's College Republicans chapter and graduating with a B.A. degree with honors in political science in 1980.[13] While at Penn State, Santorum joined the Tau Epsilon Phi fraternity.[14] He then completed a one-year M.B.A. program at the University of Pittsburgh's Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business, graduating in 1981.[15] In 1986, Santorum received a J.D. degree with honors from Dickinson School of Law.[16]

Early career

editSantorum first became actively involved in politics in the 1970s through volunteering for Senator John Heinz, a Republican from Pennsylvania.[17] Additionally, while in law school, Santorum was an administrative assistant to Republican state senator Doyle Corman, serving as Executive Director of the Pennsylvania Senate Local Government Committee from 1981 to 1984, then Executive Director of the Senate Transportation Committee.[16]

After graduating, Santorum was admitted to the Pennsylvania bar and practiced law for four years at the Pittsburgh law firm Kirkpatrick & Lockhart, a firm known for raising political candidates and lobbyists (later named K&L Gates). As an associate, he successfully lobbied on behalf of the World Wrestling Federation to deregulate professional wrestling, arguing that it should be exempt from federal anabolic steroid regulations because it was entertainment, not a sport.[18][19][20] Santorum left his private law practice in 1990 after his election to the House of Representatives.

U.S. House of Representatives (1991–1995)

editHaving been groomed by Kirkpatrick & Lockhart, Santorum decided Democratic congressman Doug Walgren was vulnerable, and took up residence in Walgren's district. Needing money and political support, he courted GOP activist and major donor Elsie Hillman,[21] the chair of the state Republican Party.[21] In 1990, at age 32, Santorum was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives to represent Pennsylvania's 18th congressional district, located in the eastern suburbs of Pittsburgh. He scored a significant upset in the heavily Democratic district, defeating seven-term Democratic incumbent Doug Walgren by a 51% to 49% margin.[22] During his campaign Santorum repeatedly criticized Walgren for living outside the district for most of the year.[23] Although the 18th District was redrawn for the 1992 elections, and the new district had a 3:1 ratio of registered Democrats to Republicans, Santorum still won reelection with 61% of the vote.[24]

In 1993, Santorum was one of 17 House Republicans who sided with most Democrats to support legislation that prohibited employers from permanently replacing striking employees.[25] He also joined a minority of Republicans to vote against the North American Free Trade Agreement that year.[26] As a member of the Gang of Seven, Santorum was involved in exposing members of Congress involved in the House banking scandal.[27]

U.S. Senate (1995–2007)

editElections

editSantorum served in the United States Senate representing Pennsylvania from 1995 to 2007. From 2001 until 2007, he was the Senate's third-ranking Republican.[28] He was first elected to the Senate during the 1994 Republican takeover, narrowly defeating incumbent Democrat Harris Wofford, 49% to 47%. The theme of Santorum's 1994 campaign signs was "Join the Fight!" During the race, he was considered an underdog, as his opponent was 32 years his senior.[29] He was reelected in 2000, defeating U.S. congressman Ron Klink by a 52% to 46% margin. In his reelection bid of 2006, he lost to Democrat Bob Casey, Jr.[30] by a 59% to 41% margin.

Tenure

editAfter his election to the Senate in 1994, Santorum sought to "practice what [he] preached" and hired five people for his staff who were on welfare, food stamps, or other government aid.[31]

In 1996, Santorum served as Chairman of the Republican Party Task Force on Welfare Reform, and contributed to legislation that became the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act. Santorum was an author and the floor manager of the bill.[32] In 1996, Santorum endorsed moderate Republican Arlen Specter in his short-lived campaign for president. Reporters have observed that though Santorum and Specter differed on social policy, Specter provided him with key political staff for his successful run in 1994.[33]

The National Taxpayers Union, a fiscal conservative organization, gave Santorum an "A−" score for his votes on fiscal issues, meaning that he was one of "the strongest supporters of responsible tax and spending policies" during his tenure, and ranked fifth in the group's rankings out of 50 senators who served at the same time.[34]

Legislative proposals

editReligious freedom initiatives

editIn 2002, Santorum was a co-sponsor of that year's attempt to pass the Workplace Religious Freedom Act (WRFA).[36] The bill had first been introduced in the Senate by Senator John Kerry (D-MA) in 1996, having been introduced in the House by Rep. Jerrold Nadler (D-NY) in 1994. Although Santorum was in the Senate at the time, he was not a sponsor of the bill when it was introduced in 1996, or when it was reintroduced in 1997 and 1999.[37][38][39] Once signed on as a co-sponsor, Santorum remained so throughout his tenure in the Senate.

Santorum founded the Congressional Working Group on Religious Freedom in 2003.[40][41] The group included members of both the Senate and the House of Representatives, and met monthly to address issues such as the Workplace Religious Freedom Act, tax-exempt status for churches, the CARE act, international religious freedom, and antisemitism.[35]

Teaching of evolution and intelligent design

editSantorum added to the 2001 No Child Left Behind bill a provision that would have provided more freedom to schools in teaching about the origins of life, including the teaching of the pseudoscience of intelligent design alongside evolution.[42][43] The bill, with the Santorum Amendment included, passed the Senate 91–8[42][44] and was hailed as a victory by intelligent design promoters,[45][46][47][48] but before it became law, scientific and educational groups successfully urged its conference committee to strike the Santorum Amendment from the final version. Intelligent design supporters in Congress then preserved the language of the Santorum Amendment in the conference committee report of the bill's legislative history.[45][46][47][48][49] The Discovery Institute and other intelligent design proponents point to this report as "a clear endorsement by Congress of the importance of teaching a variety of scientific views about the theory of evolution."[50][51]

In 2002, Santorum called intelligent design "a legitimate scientific theory that should be taught in science classes",[52] but by 2005 he had adopted the Teach the Controversy approach.[53][54] He told National Public Radio, "I'm not comfortable with intelligent design being taught in the science classroom. What we should be teaching are the problems and holes ... in the theory of evolution."[55] Later that year, Santorum resigned from the advisory board of the Christian-rights Thomas More Law Center after the Center's lawyers lost a case representing a school board that had required the teaching of intelligent design.[56] Santorum, who had previously supported the school board's policy, indicated he had not realized that certain members of the board had been motivated by religious beliefs.[56] Santorum critics said he was backtracking from his earlier position because he was facing a tough reelection fight in 2006.[56] When asked in November 2011 about his views on evolution, Santorum stated that he believes that evolution occurred on a tiny, micro level.[57]

National Weather Service Duties Act

editSantorum introduced the National Weather Service Duties Act of 2005,[58][59] which aimed to prohibit the National Weather Service from releasing weather data to the public without charge where private-sector entities perform the same function commercially.[60] The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association was organizing a lobbying effort in opposition to the legislation,[61] but it never passed committee.[61] The motivations for the bill were controversial, as employees of AccuWeather, a commercial weather company based in Pennsylvania, donated $10,500 to Santorum and his PAC.[62] The liberal advocacy group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington cited the bill as one of several reasons for listing Santorum as one of its "most corrupt politicians".[63] In support of the bill, Santorum criticized the National Weather Service in September 2005, saying its evacuation warnings for Hurricane Katrina were "insufficient".[60][64][65]

Foreign policy

editSantorum supports the War on Terror and shares the views of neoconservatives and the Bush Doctrine in regard to foreign policy. He felt the War in Iraq was justified and in 2006 declared that weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) had been found in Iraq. Santorum made the declaration regarding WMDs[66] based in part on declassified portions of the U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command.[67] The report stated that coalition forces had recovered approximately 500 weapons munitions that contain degraded or vacant mustard or sarin nerve agent casings. The specific weapons he referred to were chemical munitions dating back to the Iran–Iraq War that were buried in the early 1990s. The report stated that while agents had degraded to an unknown degree, they remained dangerous and possibly lethal.[66] Officials of the Department of Defense, CIA intelligence analysts, and the White House have all explicitly stated that these expired casings were not part of the WMDs threat that the Iraq War was launched to contain.[68]

Santorum has said the war on terror can be won and is optimistic about U.S. involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan in the long term. He has defended the treatment of prisoners in Guantanamo Bay, including waterboarding, and stated that John McCain, who opposed the practice, "doesn't understand how enhanced interrogation works."[69][70][71][72] Santorum called the War in Afghanistan "a very winnable operation" in 2012, dismissing efforts for withdrawal by 2014. He similarly criticized President Obama's foreign policy, saying he was "not focused on trying to win the war" in Afghanistan,[73] and said he was against any withdrawal in Iraq in 2012, saying, "We want victory."[74]

Santorum supports U.S. political intervention[75] and economic sanctions against state sponsors of terrorism.[76] He views "Islamic fascism" in Iran as the center of the "world's conflict", and his geopolitical strategy for peace involves the United States promoting "a strong Lebanon, a strong Israel, and a strong Iraq."[75] He sponsored the Syria Accountability Act of 2003 to require Syria to cease all activity with Lebanon and end all support for terrorism.[76] In 2005, Santorum sponsored the Iran Freedom and Support Act, which appropriated $10 million aimed at regime change in Iran. The Act passed with overwhelming support. Santorum voted against the Lautenberg amendment, which would have closed the loophole that allows companies like Halliburton to do business with Iran through their foreign affiliates.[77] Santorum reflected on his last year in the Senate as one spent talking a lot about Iran and was characterized by The Atlantic Wire as an "extreme hawk" in his approach to Iran.[78][79] Santorum stated that Iran was the creator of Hezbollah and the driving force of Hamas. He said Iran was at the center of "much of the world's conflict" but he was opposed to direct military action against the country in 2006.[75] Santorum was one of only two senators who voted against confirming Robert Gates as Secretary of Defense. He said his objection was to Gates's support for talking with Iran and Syria, because it would be an error to talk with radical Islamists.[80]

Party leadership and other actions

editSantorum became chairman of the Senate Republican Conference in 2000, the party's third-ranking leadership position in the Senate.[81] In that role, he directed Senate Republicans' communications operations and was a frequent party spokesperson. He was the youngest member of the Senate leadership and the first Pennsylvanian to hold such a prominent position since Senator Hugh Scott was Republican leader in the 1970s.[82][83] In addition, Santorum served on the Senate Agriculture Committee; the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs; the Senate Special Committee on Aging; and the Senate Finance Committee, of which he was the chairman of the Subcommittee on Social Security and Family Policy. He also sat at the candy desk for ten years.[82][83]

In January 2005, Santorum announced his intention to run for Senate Republican Whip, the second-highest post in the Republican caucus after the 2006 election, saying he expected the incumbent whip, Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, to run for Senate Republican leader to succeed Bill Frist of Tennessee, who was planning to retire.[84] As a result of Santorum's loss in the 2006 election, this plan was never realized.

K Street Project

editBeginning in 1995, Republicans leaders such as Tom DeLay and Grover Norquist initiated an order to place Republicans in lobbying firm jobs and exclude Democrats. In addition, the initiative pressured lobbying firms to contribute to Republican campaigns by withholding access to lawmakers from firms that did not comply.[85] The initiative became politically toxic for Republicans when the Jack Abramoff scandal broke in late 2004. Although some sources indicate that Santorum played a key role[86][87] in the K Street Project, he has denied any involvement.[88][89] In November 2005, several months after the indictments of Abramoff and DeLay, Santorum told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, "The K Street project is purely to make sure we have qualified applicants for positions that are in town. From my perspective, it's a good government thing."[90] A few months later, however, Santorum emphatically denied any connection with either the K Street Project or Norquist, saying: "I had absolutely nothing to do—never met, never talked, never coordinated, never did anything—with Grover Norquist and the quote K Street Project."[91] In January 2012, The Washington Post's' "Fact Checker" concluded that "we can't prove definitively whether or not Santorum collaborated on the K Street Project", saying that it "depend[ed] on how you define the initiative".[92]

2006 reelection campaign

editIn 2006, Santorum sought reelection to a third Senate term.[93] He ran unopposed in the Republican Party. His seat was considered among the most vulnerable for Republicans and was a prime target of the Democratic Party in the 2006 elections. George W. Bush had a 38% approval rating in Pennsylvania in 2006.[94] Mary Isenhour, a Democratic strategist, reflected on Santorum's campaign and his connection to the unpopular president, "In 2006, we were doubly blessed—we could run against George W. Bush and Rick Santorum".[95] Santorum chose to campaign alongside President Bush and called him a "terrific president", hurting his popularity. Also problematic was Santorum's 2004 endorsement of his Republican Senate colleague Arlen Specter over conservative congressman Pat Toomey in the primary for Pennsylvania's other Senate seat. Many socially and fiscally conservative Republicans considered the endorsement a betrayal of their cause.[96][97]

Santorum's opponent was Democratic state treasurer Bob Casey, Jr., the son of popular former governor Robert Casey, Sr. Casey was well known for his opposition to abortion, negating one of Santorum's key issues.[98] For most of the campaign, Santorum trailed Casey by 15 points or more in polls.[99] Green Party candidate Carl Romanelli failed to gain ballot access in the race, further hurting Santorum's chances. Reportedly, several of Santorum's supporters had funded and petitioned for Romanelli to siphon away Democrats from Casey.[100]

Santorum was mired in controversy and spent much of his time on the campaign defending his past statements and positions. He faced criticism from Casey and others for several statements in his book It Takes a Family, including his denunciation of 1960s "radical feminism", which he said had made it "socially affirming to work outside the home" at the expense of child care.[101] In the book, Santorum also compared pro-choice Americans to "German Nazis." John Brabender, an adviser to Santorum's Senate and presidential races, reflected back on the book's controversies and said Santorum was warned that sections could bring political damage, and Santorum was not willing to change much of it simply to gain moderate supporters.[102] In addition, a past article Santorum wrote to The Catholic Online in which he linked liberalism and moral relativism in American society, particularly within seminaries, to the Catholic Church sex abuse scandal resurfaced in 2005. He wrote, "It is no surprise that Boston, a seat of academic, political and cultural liberalism in America, lies at the center of the storm."[103][104] His remarks were heavily criticized, especially in Massachusetts, and he was asked for an explanation. Santorum did not retract his statement and defended his premise that it was "no surprise that the center of the Catholic Church abuse took place in very liberal, or perhaps the nation's most liberal area, Boston."[105] Casey also raised the question of Santorum's association with the K Street Project.[90][91][106][107]

Santorum said he spent "maybe a month a year" at his Pennsylvania home,[108] raising allegations of hypocrisy as he had denounced his former opponent Doug Walgren for living away from his House district.[109] Critics also complained that Pennsylvania taxpayers were paying 80% of the tuition for five of Santorum's children to attend an online "cyber school"—a benefit available only to Pennsylvania residents—when all his children lived in Virginia.[110] The Penn Hills School District, which covered the tuition costs for the cyber school through local taxes, unsuccessfully filed a complaint against Santorum for reimbursement in 2005,[111] but won reimbursement from the state in September 2006 in the amount of $55,000.[112][113] In response, Santorum asked county officials to remove the homestead tax exemption from his Penn Hills property, saying he was entitled to it but chose not to take it because of the political dispute.[114] Since 2006, Santorum has been home-schooling his seven children.[115][116] Santorum responded to the dispute saying that his children should not be implicated in the "politics of personal destruction".[117] One of his children appeared in a 2006 reelection campaign ad, saying, "My dad's opponents have criticized him for moving us to Washington so we could be with him more."[118]

Santorum ran a television ad suggesting that Casey's supporters had been under investigation for various crimes. The negative ad backfired, as The Scranton Times-Tribune found that all but a few of Casey's contributors donated when he was running for other offices, and none were investigated for anything.[119] In fact, two of the persons cited in Santorum's campaign ad actually contributed to Santorum in 2006, and one died in 2004.[120] Santorum's campaign countered that those donations were not kept and had been donated to educational institutions.[121]

Toward the end of his campaign, Santorum shifted his theme to the threat of radical Islam.[70][122] In October 2006 he gave a "Gathering Storm" speech, invoking British Prime Minister Winston Churchill's description of Europe prior to World War II.[70][122] As evidence that Islamists were waging a more-than-300-year-old crusade against the Western world, Santorum pointed to September 11, 1683, the date of the Battle of Vienna.[123] Casey responded, "No one believes terrorists are going to be more likely to attack us because I defeat Rick Santorum."[19] Noting that he had been "even more hawkish" during this time period than President Bush, Santorum later said, "Maybe that wasn't the smartest political strategy, spending the last few months running purely on national security".[122]

A heated debate between the candidates occurred on October 11, 2006.[124] Bill Toland of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette described both candidates' performances during the debate as "unstatesmanlike".[124]

In the November 7, 2006, election, Santorum lost by over 700,000 votes, receiving 41% of the vote to Casey's 59%. This was the largest margin of defeat for a sitting senator in the 2006 cycle, and the largest margin of defeat for an incumbent senator since 1980.[125][126]

Post-Senate career

editLawyer, political consultant and commentator

editIn January 2007, Santorum joined the Ethics and Public Policy Center, a D.C.-based conservative think tank, as director of its America's Enemies Program focusing on foreign threats to the United States, including Islamic fascism, Venezuela, North Korea and Russia.[122] In February 2007, he signed a deal to become a contributor on the Fox News Channel, offering commentary on politics and public policy.[127] In March 2007 he joined Eckert Seamans,[128] where he primarily practiced law in the firm's Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C., offices, providing business and strategic counseling services to the firm's clients. In 2007, he joined the Board of Directors of Universal Health Services, a hospital management company based in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania.[129] He also began writing an op-ed column, "The Elephant in the Room", for The Philadelphia Inquirer.[130]

Santorum earned $1.3 million in 2010 and the first half of 2011. The largest portion of his earnings—$332,000—came from his work as a consultant for industry interest groups, including Consol Energy and American Continental Group. Santorum also earned $395,414 in corporate director's fees and stock options from Universal Health Services and $217,385 in income from the Ethics and Public Policy Center.[86][131][132] In 2010 he was paid $23,000 by The Philadelphia Inquirer for his work as a columnist.[86]

In January 2017, Santorum became a CNN senior political commentator.[133] In April 2021, he claimed at an April 23 Young America's Foundation event that "There isn't much Native American culture in American culture. We came here and created a blank slate. We birthed a Nation. From nothing. I mean there was nothing here." Santorum's comments, which were described as racist,[134][135] led to calls for CNN to terminate his contract, which the network did days later.[136][137]

Speculation about political plans

editBefore the 2006 election, Santorum was frequently mentioned as a possible 2008 presidential candidate. Such speculation faded when, during the 2006 campaign and in light of unimpressive poll numbers in his Senate race, he declared that, if reelected, he would serve a full term. After he lost, Santorum once again ruled out a presidential run.[138]

On February 1, 2008, Santorum said he would vote for Mitt Romney in the 2008 Republican presidential primary.[139] Santorum criticized John McCain, questioning his anti-abortion voting record and conservative values. Santorum later said he endorsed Romney because he saw him as the "best chance to stop John McCain", whom he considered too moderate.[140] In September 2008, Santorum expressed support for McCain as the nominee, citing McCain's choice of Sarah Palin as his running mate as a step in the right direction.[141]

Santorum was mentioned as a candidate for governor of Pennsylvania in 2010.[142] At one point, he was said to have "quietly but efficiently put his fingerprints on a wide array of conservative causes in the state."[143] Santorum declined to seek the gubernatorial nomination and instead endorsed eventual winner Tom Corbett.[144]

2012 presidential campaign

editIn the fall of 2009, Santorum gave a speech at the University of Dubuque on the economy, fueling speculation that he would run for president in 2012. Santorum later recalled, "It got a lot of buzz on the Internet, so I thought, 'Wow, maybe there's some interest'". He decided to campaign after multiple conversations with his wife, who was not enthusiastic at first.[145]

On September 11, 2009, Santorum spoke to Catholic leaders in Orlando, Florida, saying that the 2012 presidential elections were going to be "a real opportunity for success." He then scheduled various appearances in Iowa with political nonprofit organizations.[146]

On January 15, 2010, Santorum sent an email and letter to supporters of his political action committee, saying, "I'm convinced that conservatives need a candidate who will not only stand up for our views, but who can articulate a conservative vision for our country's future". He continued, "And right now, I just don't see anyone stepping up to the plate. I have no great burning desire to be president, but I have a burning desire to have a different president of the United States".[147] He formed a presidential exploratory committee on April 13, 2011. Santorum also mentioned his grandfather's historical encounter with Italian fascism as an inspiration for his presidential campaign.[148]

He formally announced his run for the Republican presidential nomination on ABC's Good Morning America on June 6, 2011, saying he was "in it to win." He initially lagged in the polls but gained as other conservative candidates slumped. By the weekend before the Iowa caucuses, polls showed him in the top three along with Romney and Ron Paul.[149][150] The Des Moines Register also noted that the momentum was with Santorum. In the closest finish in the history of the Iowa caucuses, the count on the night put Romney as winner by a margin of eight votes, but the final result announced two weeks later showed that Santorum had won by 34 votes.[151] Santorum later focused on the states holding votes on February 7, a strategy that paid off, as he won all three.[152][153] Santorum surged in polls taken shortly after, ranking first in some and a close second in others.[154] In the March 13 primaries, Santorum narrowly won both Mississippi and Alabama[155] and followed up with a victory in Louisiana on March 24.[156]

Following the hospitalization of his daughter Bella and losses in Wisconsin, Maryland, and the District of Columbia, Santorum announced the suspension of his campaign on April 10, 2012, in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[157][158] He had won 11 state primaries and nearly 4 million votes, more than any other candidate except Romney.[159] Santorum topped Romney in polls for a brief period. Upon the conclusion of Santorum's run, Romney called him "an important voice" in the GOP.[160]

Santorum received a prime time speaking slot at the 2012 Republican National Convention. He was originally slated to speak early in the evening, but convention organizers moved him to 9 pm with the other highly anticipated speakers of the evening, Ann Romney and convention keynote Chris Christie.[161] Santorum spoke of the American dream his immigrant grandfather worked to give his family and said Obama was turning the dream into a nightmare.[162] He talked about his experiences on the presidential campaign trail, speaking with emotion about his daughter Bella and meeting disabled people and their families.[163] He emphasized the importance of strengthening marriage and the family.[164] He also condemned Obama's actions on the welfare reform law,[165] of which he was one of the chief proponents in Congress, and his actions on education, including school choice and student loans.[166] Santorum concluded his speech to a standing ovation, saying,

I thank God that America still has one party that reaches out their hands in love to lift up all of God's children—born and unborn—and says that each of us has dignity and all of us have the right to live the American Dream. And without you, America is not keeping faith with that dream. We are stewards of a great inheritance. In November we have a chance to vote for life and liberty, not dependency. A vote for Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan will put our country back in the hands of leaders who understand what America can and, for the sake of our children, must be to keep the dream alive.[164][167]

Patriot Voices

editIn June 2012, Santorum launched Patriot Voices, a 501(c)(4) nonprofit with a mission to "mobilize conservatives around this country who are committed to promoting faith, family, freedom and opportunity" in support of causes and candidates across the country.[168] Santorum supported U.S. Senate candidates Ted Cruz in Texas and Richard Mourdock in Indiana in their respective Republican primaries; both won.[169] In the general elections, Patriot Voices endorsed eight U.S. Senate candidates and four House candidates.[170] In Iowa's 2012 retention elections Santorum lent support to the "NO Wiggins" effort to oust Iowa Supreme Court Justice David Wiggins, who they say promulgated a personal political agenda in the court.[171] They have also been vocal in opposition to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which they say threatens parental rights and U.S. sovereignty.[172] In August 2021 Santorum became a Senior Advisor to the Convention of States Project of Citizens for Self-Governance. "As Senior Advisor, Rick is counseling us on strategy, will serve as a public voice for the surging Convention of States movement, and will focus his incredible energy on restoring our nation and returning the proper balance to our republic," said Mark Meckler, head of the Convention of States Project.

Business ventures

editIn June 2013, Santorum became Chairman and CEO of EchoLight Studios, a Dallas-based Christian movie company.[173] Santorum has produced the Christmas-themed movie The Christmas Candle[174] and the religious liberty film One Generation Away.[175]

He is a part owner of Plasma Technologies LLC.[176]

2016 presidential campaign

editAppearing on NBC's Meet the Press on August 4, 2013, Santorum said, "I'm open to looking into a presidential race in 2016."[177] He outlined plans for a potential 2016 run in an interview with The Washington Post,[178] and officially announced his candidacy on May 27, 2015.[179] After performing poorly in the Iowa caucuses, Santorum ended his campaign on February 3, 2016,[180] and endorsed Florida senator Marco Rubio.[181] After Rubio suspended his campaign, Santorum endorsed Donald Trump.[182]

CNN racism accusation

editIn May 2021, Santorum stated that America was founded by white Europeans and that prior to their arrival, America was populated by nothing more than a handful of primitive warring Native American tribes. He was dropped from CNN over these remarks, with some responses referring to them as "classic white supremacist rhetoric" and being "dangerous manipulation".[183][184][185] In response, Santorum said he had “misspoke” and denied that he was “trying to dismiss [the genocide of] Native Americans”.[183]

Political positions

editSantorum has consistently held socially conservative views and has advocated "compassionate conservatism".[186] He has a more mixed record on fiscal issues.[187] As a member of Congress, he voted for the Bush tax cuts, favored a balanced budget amendment and sought to curb entitlements, playing a key role in enacting welfare cuts.[187] He has been criticized for supporting costly federal programs in education and transportation and for using earmarks to fund Pennsylvania projects.[187] He says he regrets many of his votes for such programs and opposes earmarks.[187] He has also specifically disavowed his 2003 support for the unfunded Medicare prescription drug benefit and his vote for the No Child Left Behind Act.[187][188]

In 2003, he was described by the Pennsylvania Report as having a "confrontational, partisan, 'in your face' style of politics and government."[189] "I just don't take the pledge. I take the bullets", Santorum said. "I stand out in front and I lead to make sure the voices of those who do not have a voice are out in front and being included in the national debate."[190]

Abortion

editSantorum considered himself pro-choice on abortion throughout his early life but adopted an anti-abortion position by 1990 when he ran for Congress.[191][192][193] He has become known for his staunch opposition to abortion.[194][195][196] In 2015, he said, "'I do not believe life begins at conception. I know life begins at conception. This is not a matter of debate. It's not a matter of faith ... Every child at the moment of conception is both living—that embryo is metabolizing—and it is ... genetically completely human"'.[196] During a 2016 presidential debate, Santorum said, "'Twice in my life we were counseled to have an abortion—once with our son Gabriel and one with our little girl, Bella ... Neither time did Karen (Santorum's wife) and I even think about [an abortion], because we know life begins at conception'".[194]

In 1996, Santorum led the unsuccessful attempt to override President Bill Clinton's veto of the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 1995,[197] He also sponsored a similar bill in 1999.[198] Santorum was a lead sponsor of the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act,[199] which was signed into law by President George W. Bush in November 2003[200] and upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in the 2007 decision Gonzales v. Carhart.[201]

Class/Inequality

editSantorum has condemned the term "middle class" as "Marxism talk" used by liberals, maintaining that the United States has no social classes.[202][203] At an August 2013 GOP fundraiser in Rock Rapids, Iowa, he said, "Don't use the term the other side uses... [t]he middle class.... Since when in America do we have classes? Since when in America are people stuck in areas or defined places called a class? That's Marxism talk... When Republicans get up and talk about middle class, we're buying into their rhetoric of dividing America. Stop it. There's no class in America. Call them on it."[202]

Contraception

editSantorum has said he does not believe a "right to privacy" is part of the Constitution. He has criticized the Supreme Court decision in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which held that the Constitution guaranteed that right and overturned a law prohibiting the sale of contraceptives to married couples.[204] Santorum has asserted that the right to privacy set forth in Griswold was a "jurisprudential novelty [that] quickly become a constitutional wrecking ball" and eventually led the Court to recognize a constitutional right to abortion in Roe v. Wade (1973).[204] In critiquing Griswold, Santorum emphasized that he did not support laws banning contraceptives.[204] Santorum has, however, described contraception as "a license to do things in [the] sexual realm that [are] counter to how things are supposed to be."[205]

Death penalty

editIn March 2005, Santorum expressed misgivings about the death penalty in light of wrongly convicted individuals who were sentenced to death. He went on to say, "I agree with the Pope that in the civilized world... the application of the death penalty should be limited. I would definitely agree with that. I would certainly suggest there probably should be some further limits on what we use it for."[206] In January 2012, Santorum said that "when there is certainty, that's the case that capital punishment can be used" but that "if there is not certainty, under the law, it shouldn't be used."[207]

Drugs

editSantorum used cannabis in college, but later said, "Even during that time, I knew that what I was doing was wrong."[208] He is against the legalization of cannabis and believes that the federal law against it should be enforced in Colorado.[209] He has voted in favor of increasing penalties for drug trafficking and possession and for increased spending on drug control.[208]

Energy and environment

editSantorum rejects the overwhelming scientific consensus on climate change, which states that global warming is harmful and primarily human-caused, calling it "junk science". He has claimed that global warming is a "beautifully concocted scheme" by the political left and "an excuse for more government control of your life."[210]

In reaction to Pope Francis's encyclical Laudato si', which acknowledges man-made climate change and calls for swift and unified global policies to phase out fossil fuels, Santorum said in 2015: "The Church has gotten it wrong a few times on science, and I think we probably are better off leaving science to the scientists and focusing on what we're good at, which is theology and morality."[211][212]

He has stated a policy of "drill everywhere" for oil and that there is "enough oil, coal and natural gas to last for centuries".[213]

Euthanasia

editIn 2012, Santorum said that half of all euthanizations in the Netherlands are involuntary, that Dutch hospitals euthanize elderly patients for financial reasons, and that 10% of all deaths in the Netherlands are the result of involuntary euthanizations. Santorum's statements were called "bogus" by FactCheck.org,[214] and Glenn Kessler, fact-checker for The Washington Post, said there was no evidence to support them.[215] Santorum's comments were met with a significant backlash in the Netherlands and were significantly criticized worldwide.[216]

Fiscal policy

editAs U.S. representative from Pennsylvania, in each year from 1992 through 1994 Santorum received a grade of B, and as U.S. senator from Pennsylvania he received grades of A from 1995 through 1997, B+ in 1998 and 1999, B in 2000, A from 2001 through 2004, B in 2005, and B+ in 2006 from the National Taxpayers Union, a conservative taxpayers advocacy organization.[217][218]

Gun laws

editSantorum, who received nearly $116,000 from the gun lobby from 1990 to 2017, has consistently supported gun rights.[219][220] Santorum is an advocate of the right to bear arms. He is also a defender of gun manufacturers, and voted for the 2005 Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (Bill S 397), which prevents civil suits from being brought against gun manufacturers for criminal acts perpetrated with their weapons.[221] On March 25, 2018, in response to the "March for Our Lives", Santorum told CNN that rather than marching the students should "take CPR classes" instead of "looking to someone else to solve their problems."[222] Columbia Journalism Review called the comment "asinine on its face," but said that, even so, the response from doctors, journalists and students about the "stupid" comment was excessive.[223]

Immigration

editIn 2015, Santorum called for more restrictions on family-based immigration after warning of a "flood of legal—not illegal—immigrants to our country", which he blamed for depressing the median income of American workers.[224]

In 2006, Santorum opposed the Senate's immigration reform proposal, saying the U.S. should simply act to enforce currently existing laws. He has openly stated his opposition to amnesty for illegal immigrants. He supports the construction of a barrier along the U.S.–Mexican border, an increase in the number of border patrol agents, and the stationing of National Guard troops along the border. He also believes that illegal immigrants should be deported immediately when they commit crimes and that undocumented immigrants should not receive benefits from the government. He believes English should be established as the national language in the United States.[225] Santorum cites his own family's history (his father immigrated to the U.S. from Italy) as proof of how to immigrate "the right way".[226]

At the 2015 Iowa Freedom Summit, Santorum said the volume of legal immigration into the United States is also too high, and stated that the number of immigrants lawfully entering the country was "affecting American workers" by taking jobs and lowering wages.[227][228] Santorum claimed that all "net new jobs" created in the United States economy since 2000 have gone to immigrants (both legal and illegal).[229] At the Iowa Freedom Summit, Santorum said: "We need an immigration policy that puts American workers first."[227]

Libertarianism

editIn June 2011, Santorum said he would continue to "fight very strongly against libertarian influence within the Republican Party and the conservative movement."[230] In an interview with NPR in the summer of 2005, Santorum discussed what he called the "libertarianish right", saying "they have this idea that people should be left alone, be able to do whatever they want to do. Government should keep our taxes down and keep our regulation low and that we shouldn't get involved in the bedroom, we shouldn't get involved in cultural issues, you know, people should do whatever they want. Well, that is not how traditional conservatives view the world, and I think most conservatives understand that individuals can't go it alone."[231]

Minimum wage

editDuring his 2016 presidential campaign, Santorum came out in support of an increase in the federal minimum wage. In September 2015, he said, "'Republicans are losing elections because we aren't talking about [workers], all we want to talk about is what happened to business, there are people that work in those businesses.'"[232]

Paid family leave

editSantorum supports paid family leave.[233]

Pornography

editOn his website, Santorum said that the "Obama Administration has turned a blind eye" to pornography, but promised the situation would "change under a Santorum Administration."[234] According to USA Today, some conservatives believe Santorum's opposition to pornography could "hurt the party politically."[234] On March 23, 2012, Santorum wrote on his campaign website that there is "a wealth of research" demonstrating that pornography causes "profound brain changes" and widespread negative effects on children and adults, including violence to women.[235] Researchers say that there is no such evidence of brain changes, although pornography's harmfulness "is still in dispute."[235]

Santorum defended his assertions by saying that "the Obama Department of Justice seems to favor pornographers over children and families", and that the department's failure to prosecute the porn industry "proves his point."[236] He then said that Obama had not put a priority on tackling the porn industry, "putting children at risk as a result of that."[236] In a position paper circulated in March 2012, Santorum said he would order his attorney general to "vigorously enforce" existing laws that "prohibit distribution of hardcore (obscene) pornography on the Internet, on cable/satellite TV, on hotel/motel TV, in retail shops and through the mail or by common carrier."[237]

LGBT issues

editIn his 2005 book It Takes a Family, Santorum advocated a society oriented toward "family values" and centered on monogamous, heterosexual relationships, marriage, and child raising. He opposes both same-sex marriage and civil unions, saying the American public and their elected officials should decide on these "incredibly important moral issues" rather than the Supreme Court.[238]

During a 2003 interview, Santorum expressed opposition to same-sex marriage, said he favors having laws against polygamy, sodomy (between same sex or opposite sex couples), and other actions "antithetical to a healthy, stable, traditional family", and likened homosexuality to bestiality and child sexual abuse.[239][240] The remarks drew a retaliatory response from many, including author, journalist, and LGBT community activist Dan Savage, who launched a contest to coin a "santorum" neologism among the readers of his blog with the winner as "the frothy mixture of lube and fecal matter that is sometimes the byproduct of anal sex".[241][242] The website Savage set up for the campaign became one of the top search results for Santorum's surname,[243] creating a situation that commentators dubbed "Santorum's Google problem".[242][244] Santorum has characterized the campaign as a "type of vulgarity" spread on the Internet.[244] In September 2011, Santorum unsuccessfully requested that Google remove the content from its search engine index.[245] In 2015, during an interview on The Rachel Maddow Show, he expressed regret for making the "man-on-dog" statement, which he described as "flippant", but added: "[T]he substance of what I said ... I stand by that."[246][247]

In 2011, during his bid for the Republican nomination in the upcoming presidential election, Santorum attended a Republican primary debate held two days after the official end of the Clinton-era "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy that effectively banned gays and lesbians from open service in the United States Armed Forces and fielded a question from Stephen Snyder-Hill, a gay soldier then serving in Iraq, about the progress made by gay soldiers in the military.[248] The soldier was booed by some in the audience, and Santorum said his administration would reinstate the ban on gay soldiers in the military. Santorum was roundly criticized for not supporting the soldier, and he later asserted he had not heard the booing from the stage.

In 2015, Santorum signed an online pledge vowing not to respect any law, including any decision by the United States Supreme Court, conferring legal recognition on same-sex marriage.[249] The pledge states, in part: "A decision purporting to redefine marriage flies in the face of the Constitution and is contrary to the natural created order. As people of faith we pledge obedience to our Creator when the State directly conflicts with higher law."[250] In April 2015, Santorum stated on Hugh Hewitt's radio program that he would not attend a same-sex wedding, saying: "as a person of my faith, that would be something that would be a violation of my faith."[251]

At a Republican convention in South Carolina in 2015, Santorum responded to a question about Caitlyn Jenner by saying: "if [Jenner] says he's a woman, then he's a woman. My responsibility as a human being is to love and accept everybody. Not to criticize people for who they are."[252] Due to Santorum's consistent opposition to same-sex marriage, his apparent acceptance of Jenner's transition surprised some.[who?][253] Some people criticized Santorum for continuing to use the male pronoun in reference to Jenner.[254] Santorum declined to take a position on whether transgender people should be allowed to use restrooms of the gender of their choice, saying only that he believed the federal government should leave the issue to local authorities.[255][256] Santorum later clarified his statement, writing that he "meant to express empathy", and "not a change in public policy."[256]

Poverty

editWhile in Congress, Santorum supported efforts to fight global HIV/AIDS,[257] provide assistance to orphans and vulnerable children in developing countries, combat genocide in Sudan, and offer third world debt relief.[258] In 2006, rock musician and humanitarian Bono said of Santorum, "he has been a defender of the most vulnerable."[259][260] On the domestic front, Santorum supported home ownership tax credits, savings accounts for children, rewarding savings by low-income families, funding autism research, fighting tuberculosis, and providing housing for people with HIV/AIDS. He supported increased funding for Social Services Block Grants and organizations like Healthy Start and the Children's Aid Society, and financing community health centers.[259]

Social Security

editSantorum supported partial privatization of Social Security, and following President Bush's reelection, he held forums across Pennsylvania on the topic.[261]

Trade policy

editThe Cato Institute's Center for Trade Policy Studies identified Santorum, during his U.S. Senate tenure, as having a mostly pro-free trade and mostly anti-subsidies voting record.[262]

Electoral history

edit| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rick Santorum | 1,735,691 | 49.40% | ||

| Democratic | Harris Wofford (incumbent) | 1,648,481 | 46.92% | ||

| Patriot Party | Diane G. Blough | 69,825 | 1.99% | ||

| Libertarian | Donald Ernsberger | 59,115 | 1.68% | ||

| Write-in | 249 | 0.01% | |||

| Total votes | 3,513,361 | 100.00% | |||

| Republican gain from Democratic | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Rick Santorum (incumbent) | 2,481,962 | 52.4% | ||

| Democratic | Ron Klink | 2,154,908 | 45.5% | ||

| Libertarian | John Featherman | 45,775 | 1.0% | ||

| Constitution | Lester Searer | 28,382 | 0.6% | ||

| Reform | Robert Domske | 24,089 | 0.5% | ||

| Total votes | 4,735,116 | 100.00% | |||

| Republican hold | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Bob Casey, Jr. | 2,392,984 | 58.64% | ||

| Republican | Rick Santorum (incumbent) | 1,684,778 | 41.28% | ||

| Write-in | 3,281 | 0.08% | |||

| Total votes | 4,081,043 | 100.00% | |||

| Democratic gain from Republican | |||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Mitt Romney | 10,031,336 | 52.13% | |

| Republican | Rick Santorum | 3,932,069 | 20.43% | |

| Republican | Newt Gingrich | 2,734,571 | 14.21% | |

| Republican | Ron Paul | 2,095,762 | 10.89% | |

| Republican | Jon Huntsman | 83,918 | 0.44% | |

| Republican | Rick Perry | 54,769 | 0.28% | |

| Republican | Michele Bachmann | 35,089 | 0.21% | |

| Republican | Buddy Roemer | 33,588 | 0.17% | |

| Republican | Herman Cain | 40,666 | 0.07% | |

| Republican | Fred Karger | 12,743 | 0.06% | |

| Republican | Gary Johnson | 4,293 | 0.02% | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Donald Trump | 14,015,993 | 44.95% | |

| Republican | Ted Cruz | 7,822,100 | 25.08% | |

| Republican | John Kasich | 4,290,448 | 13.76% | |

| Republican | Marco Rubio | 3,515,576 | 11.27% | |

| Republican | Ben Carson | 857,039 | 2.75% | |

| Republican | Jeb Bush | 286,694 | 0.92% | |

| Republican | Rand Paul | 66,788 | 0.21% | |

| Republican | Mike Huckabee | 51,450 | 0.16% | |

| Republican | Carly Fiorina | 40,666 | 0.13% | |

| Republican | Chris Christie | 57,637 | 0.18% | |

| Republican | Jim Gilmore | 18,369 | 0.06% | |

| Republican | Rick Santorum | 16,627 | 0.05% | |

Personal life

editSantorum met his future wife, Karen Garver (born 1960), while she was a neonatal nurse studying law at the University of Pittsburgh and he was recruiting summer interns for Kirkpatrick & Lockhart. They married in 1990[11] and have seven living children.

In 1996, the Santorums' son Gabriel was born prematurely after 20 weeks of pregnancy and died in the hospital two hours later. Karen wrote that she and Rick slept with Gabriel's body between them in the hospital that night and brought his body home the following day so that their other children could see him.[81][265][266] The Santorums' four eldest children appeared with their parents on Piers Morgan Tonight in January 2012. Elizabeth, who was five at the time of Gabriel's death, said she was glad to have seen him, and that he holds a place in her heart.[267]

Santorum traveled, in 2002, to Rome to speak at a centenary celebration of the birth of Saint Josemaría Escrivá, founder of Opus Dei.[268][269] He and his wife were invested as Knight and Dame of Magistral Grace of the Knights of Malta in a ceremony at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York on November 12, 2004.[270]

In 2012, Santorum's net worth was estimated to be between $880,000 and $3 million,[271] mainly held as five rental properties around Penn State University,[272] two personal homes in Great Falls and Penn Hills,[273] and some IRAs.[274] In 1997, Santorum purchased a three-bedroom house in the Pittsburgh suburb of Penn Hills. In 2001, he bought a $640,000 house in Leesburg, Virginia,[131] sold it in 2007 for $850,000,[275] and purchased a $2 million home in Great Falls, Virginia.[276]

According to The Washington Post, Santorum has paid $50,000 per year out of pocket for medical expenses not covered by insurance for his daughter Isabella's Trisomy 18.[277][278] The Santorums once paid $25,000 to have Isabella airlifted from a Virginia hospital to a children's hospital in Philadelphia.[278]

In his free time, Santorum is an avid fantasy baseball player.[279]

Religion

editAlthough he was raised in a nominally Catholic household, Santorum's faith began to deepen when he met his future wife, Karen. By his account, conversations with her father, Kenneth Garver, a staunch Catholic and abortion opponent, solidified his understanding and opposition to abortion. He and his wife have since become increasingly religious.[280] Santorum now considers himself a devout Catholic and acknowledges his faith as the source of his politics and worldview.[281] He attends Mass almost daily and organized a Catholic study group for lawmakers while in Congress.[282]

Santorum proudly calls himself a culture warrior and true Christian conservative. In so positioning himself, he has garnered popularity among Protestant evangelicals, but his support among Catholics is not as robust.[283][284] Santorum's emphasis on his "Christian roots" was especially favored by evangelicals in the Midwest and Southern states during the 2012 primaries, although he lost the Republican Catholic vote in most states to Romney.[285] Exit polls found only 42% of those Catholics and less than a third of Protestant evangelicals knew Santorum was Catholic.[286] After Santorum won Protestant-majority states Alabama and Mississippi but lost in heavily Catholic Puerto Rico, The Huffington Post said he "seemed exasperated by the trend"[287] and said his base support came from "people who take their faith seriously", not necessarily fellow Catholics.[287]

Santorum has written for Catholic publications and frequently comments on political issues from a religious standpoint. He has said, "I don't believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute. The First Amendment means the free exercise of religion and that means bringing people and their faith into the public square."[288][289] In an interview with the National Catholic Reporter, Santorum said that the distinction between private religious conviction and public responsibility, espoused by President John F. Kennedy, had caused "great harm in America". He said: "All of us have heard people say, 'I privately am against abortion, homosexual marriage, stem cell research, cloning. But who am I to decide that it's not right for somebody else?' It sounds good, but it is the corruption of freedom of conscience."[268] He told a group of college students in 2008 that the United States had been founded on "Judeo-Christian" ethics, and now "it is a shambles, it is gone from the world of Christianity as I see it."[290]

Santorum has said he values faith over politics and considers politicians' faith significant. He questioned whether Barack Obama truly has a religion, alleging that he may have chosen Christianity as a politically expedient platform for power.[291] Santorum has said that "if the president says he's a Christian, he's a Christian" but has stated that Obama's agenda was based on a "phony theology", not the Bible.[292] In an interview with Glenn Beck, Santorum said Obama's desire for greater higher education rates nationwide was a veiled attempt at "indoctrination", saying that "62 percent of kids who go into college with a faith commitment leave without it." Santorum declined to provide a source for that figure.[293][294] He believes colleges reinforce secular relativism and antagonize religiosity, particularly Christianity, and lists young people's support for abortion, gay marriage, and pornography as "symptoms" of indoctrination.[295]

Books

editSantorum has written four books: It Takes a Family: Conservatism and the Common Good (2005);[296] American Patriots: Answering the Call to Freedom (2012);[297] Blue Collar Conservatives: Recommitting to an America That Works (2014);[298] and Bella's Gift: How One Little Girl Transformed Our Family and Inspired a Nation (2015).[299] In addition to Santorum's books, a collection of his speeches as a U.S. senator was published and released by Monument Press in 2005 under the title Rick Santorum: A Senator Speaks Out on Life, Freedom, and Responsibility.

Santorum also wrote a foreword to William A. Dembski's 2006 Darwin's Nemesis: Phillip Johnson and the Intelligent Design Movement[300] and a 2006 autobiography.[301]

In It Takes a Family, Santorum argues that the traditional family is the foundation of society. Santorum criticizes alike laissez-faire conservatives and liberal proponents of social welfare for promoting a radical view of autonomy. In particular, he criticizes the "bigs" – "big government, big media, big entertainment, big universities." The book became a New York Times bestseller.[302]

American Patriots tells the stories of 25 lesser-known Americans from the American Revolution.[303] Santorum writes, "Most Americans know something about our Founding Fathers and their role in creating the government of the United States. However, most know little about the day-to-day battles fought by Americans of all backgrounds that paved the way for the high ideals of our founders to be put into practice."[304] He also writes, "Today we are facing a threat to the very foundation our founders laid. That threat does not come from an alien force but from those who are willing and determined to abandon the concept of God-given rights. Like the royalty during the Revolution, today's elites wish to return to the pre-Revolutionary paradigm in which they, through governmental force, allocate rights and responsibilities."[304]

Blue Collar Conservatives departs from traditional Republican orthodoxy[305] and says that the Republican Party must appeal to blue collar Americans. He says, "As many as six million blue collar voters stayed home from the polls, and there's good reason to believe that a large majority of them would have voted Republican if they had voted."[305] Santorum puts forward a recipe for Republican success in which Republicans advocate for workers and not just corporations.[306] He says that many middle class workers who have been forced into part-time jobs at big box stores or even into public assistance programs are amenable to the GOP's message if it is presented in relatable terms.[306] He tackles education, saying the current system of government-run schools is a "relic of the late 19th century" and that children should not be pressured into going to college when a job or vocational training would be a better option.[306] He criticizes libertarian influence in the Republican Party, saying, "There are some in my party who have taken the ideal of individualism to such an extreme that they have forgotten the obligation to look out for our fellow man."[305] He says the GOP should be less quick to dismiss concerns over decreasing social and economic mobility, saying that large businesses and stocks are strong, while life has become "a trickle" for workers.[305] He questions rich compensation of business executives, and says that while he supports free trade, Republicans need to look at its impact on the average person and consider whether existing laws are fair.[305]

In January 2015, Santorum announced Bella's Gift: How One Little Girl Transformed Our Family and Inspired a Nation, a book about his daughter Bella, who lives with a rare genetic condition called Trisomy 18. The book is authored by Santorum and his wife, Karen Santorum, and co-authored by their daughter, Elizabeth Santorum. It was released February 10, 2015.[307]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "CNN Drops Rick Santorum After Dismissive Comments About Native Americans". The New York Times. May 22, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ "GOP Candidate Rick Santorum's Daughter Hospitalized In Virginia". CBS. January 31, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ^ a b "Aldo Santorum Obituary". Legacy.com. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Town Hall – Pennsylvania's Marketplace of Ideas". Patownhall.com. January 15, 2011. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Zito, Salena (January 21, 2011). "Psychologist Aldo Santorum devoted career to fellow veterans". Pittsburgh Tribune-Review. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ "The Senator's Biography". Santorum's Senate website. Archived from the original on December 30, 2006. Retrieved December 30, 2006.;

Steve Goldstein (April 17, 2005). "Big Profile, Big Target". Beaver County Times.

"Santorum genealogy". Freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.com. Retrieved June 18, 2010.;

The Pennsylvania Manual. Dept. of General Services for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. January 6, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2011. - ^ Paul West (February 26, 2012). "Santorum and Romney fight their own class war in Michigan". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ball, Molly (January 2, 2012). "Who Is Rick Santorum?". The Atlantic. Retrieved January 20, 2012. quoting a 2005 article: Newall, Mike (October 5, 2005). "The Path of the Righteous Man: How Rick Santorum became the nation's evangelical poster boy". Philadelphia CityPaper. Archived from the original on January 23, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

Everybody called him "Rooster" because of a strand of hair on the back of his head which stood up, and because of his competitive, in-your-face attitude. 'He would debate anything and everything with you, mostly sports,' says Goettler. 'He was like a rooster. He never backed down.'

- ^ Melinda Henneberger (December 15, 2011). "Rick Santorum is long on substance, short on support". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ Butler Senior High School classbook, The Magnet, 1975

- ^ a b "Nation & World: 20 things about Rick Santorum – U.S. News & World Report". Usnews.com. June 16, 2006. Retrieved January 11, 2012.

- ^ Tony Scifo (November 5, 1996). "Carmel's political alumni return for chat with students Carmel High School". Daily Herald.

- ^ Murray, Michael (August 26, 2011). "Santorum to visit Penn State". The Daily Collegian. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ Cherkis, Jason (March 5, 2012). "Rick Santorum's Frat Brothers Perplexed By Claims Of Cultural Oppression". HuffPost. Retrieved June 30, 2012.

- ^ New York Times At a Glance: Rick Santorum October 1, 2011

- ^ a b The Pennsylvania Manual Archived June 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Vol 116, Section Eight: The Federal Government, pp. 8–11, 2003. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ^ Cherkis, Jason (February 26, 2012). "Rick Santorum: A Conservative Who Once Defended Labor Unions, Gays In Military, Art Funding". HuffPost. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ^ Tapper, Jake (January 4, 2012). "Rick Santorum, Mr. Bipartisan Compromise – and Mr. Pro Wrestling?". ABC News. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Ball, Molly (January 2, 2012). "11 Things You Might Not Know About Rick Santorum". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 7, 2013. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Thomas (October 22, 2010). "Conn. race a body slam – with Pa. ties: GOP Senate hopefuls rise got boost from Santorum". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. A.1.

- ^ a b Konigsberg, Eric (1995). "A Funny Thing Happened On the Way To Santorum" (PDF). Philadelphia. 86 (12). Metrocorp: 150. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "The Pittsburgh Press, November 7, 1990". Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "Santorum elated at upset victory to win 18th District seat in Congress". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. November 7, 1990. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "Santorum, Klink win House races". Observer Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. November 4, 1992. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Greg Giroux; Heidi Przybyla (January 4, 2012). "Santorum Pro-Labor Votes Lurk as Rivals Attack Early on Earmarks". Bloomberg News.

- ^ John Vaught LaBeaume (January 9, 2012)"Santorum to Examiner: Stands by '93 NAFTA 'nay'" Archived February 10, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Washington Examiner

- ^ Toeplitz, Shira (January 25, 2012). "Santorum and Gingrich Share Complicated Past". Roll Call. Retrieved April 27, 2016.

- ^ "Rick Santorum News and Video". Fox News. April 7, 2010. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Rick Santorum – Politics News Story – WRTV Indianapolis". Theindychannel.com. October 17, 2011. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ "Fact Check: Is Santorum the Biggest (Senate) Loser?" NJ Today. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ Santorum, Rick. Blue Collar Conservatives: Recommitting to an America that Works. Regnery Publishing, 2014, p. 97.

- ^ Hicks, Josh (January 12, 2012). "Rick Santorum and welfare reform (Fact Checker biography)". The Fact Checker. The Washington Post. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ Reeves, Frank; Torry, Jack; Shelly, Peter J. (November 26, 1995). "Santorum says he's in no hurry to back candidate". Pittsburgh Post–Gazette. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Was Santorum a Senate Spendthrift?". The Weekly Standard. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Senate Religious Freedom Agenda" (PDF). The United States Senate. Retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ "S.2572 – Workplace Religious Freedom Act of 2002". The Library of Congress. May 23, 2002. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status: 104th Congress (1995 – 1996) S.2071". The Library of Congress (Thomas). Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "S.1124 – Workplace Religious Freedom Act of 1997". Congress.gov. October 21, 1997. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status 106th Congress (1999 – 2000) S.1668 Cosponsors". The Library of Congress (Thomas). Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- ^ "Congressional Record – 109th Congress (2005-2006) – THOMAS (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. February 16, 2006. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ "Congressional Record—Senate" (PDF). U.S. Government Printing Office. February 16, 2006. pp. S1407–409.

- ^ a b Peter Slevin (March 14, 2005). "Battle on Teaching Evolution Sharpens". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Is There a Federal Mandate to Teach Intelligent Design Creationism?" (PDF). National Center for Science Education. Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- ^ "We'd Like Some Answers Origin of man, universe continues to cause debate". Alumni News Stories. Oral Roberts University Alumni Foundation. Archived from the original on February 16, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2006.

- ^ a b "Language on evolution attached to education law". Issues in Science and Technology. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Spring 2002. Archived from the original on December 12, 2007. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Kitzmiller v. Dover Area School District. p. 89. "ID's backers have sought to avoid the scientific scrutiny ... by advocating that the controversy, but not ID itself, should be taught in science class. This tactic is at best disingenuous ..."

- ^ a b George J. Annas (May 25, 2006)."Intelligent Judging – Evolution in the Classroom and the Courtroom". New England Journal of Medicine. 354:2277–2281. "... as long as the controversy is taught in classes on current affairs, politics, or religion, and not in science classes, neither scientists nor citizens should be concerned."

- ^ a b "AAAS Statement on the Teaching of Evolution" Archived February 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. American Association for the Advancement of Science. February 16, 2006. "... there is no significant controversy within the scientific community about the validity of the theory of evolution. The current controversy surrounding the teaching of evolution is not a scientific one."

- ^ Santorum, Rick (December 18, 2001). "No child left behind act of 2001—conference report". Congressional Record. p. S13377. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ Phillip E. Johnson (May 9, 2003). "Intelligent Design, Freedom, & Education". Breakpoint.org and Discovery Institute News. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2006.

- ^ Bruce Chapman; David DeWolf. "Why the Santorum Language Should Guide State Science Education Standards" (PDF). Discovery Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2006. Retrieved August 23, 2006.

- ^ Rick Santorum (March 14, 2002). "Illiberal Education in Ohio Schools". The Washington Times.

- ^ Rick Santorum (January 14, 2005). "Teach the Controversy". Allentown Morning Call.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Annas, George J. (2006). "Intelligent Judging – Evolution in the Classroom and the Courtroom". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (21): 2277–81. doi:10.1056/NEJMlim055660. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 16723620.

- ^ "Rick Santorum, 'It Takes a Family'". Interview with Rick Santorum. National Public Radio Morning Edition. August 4, 2005.

- ^ a b c "Santorum Breaks With Christian-Rights Law Center". The Washington Post. December 23, 2005. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ Mirkinson, Jack (September 8, 2011). "Chris Matthews, Rick Santorum argue after Republican debate (video)". HuffPost. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "ADDS – Aviation Digital Data Service". Aviationweather.gov. June 24, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ "National Weather Services Duties Act of 2005 (Introduced in Senate)". April 21, 2005. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved August 23, 2006.

- ^ a b Babington, Charles (September 10, 2005). "Some GOP Legislators Hit Jarring Notes in Addressing Katrina". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ a b "AOPA Online: Air Traffic Services Brief – National Weather Service Duties Act of 2005 – Santorum Bill S. 786". Aopa.org. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Election '06". The Sunday Patriot – News. Harrisburg, Pa. August 27, 2006. p. A02.

- ^ "Sen. Rick Santorum (R-PA)". Citizens for Ethics. Archived from the original on July 16, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- ^ Dorman, Todd (January 2, 2012). "Todd Dorman column". The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

- ^ "Corruption Roll Call". Multinational Monitor. Vol. 27, no. 3. May–June 2006. pp. 15–23.

- ^ a b "Report: Hundreds of WMDs Found in Iraq". Fox News. June 22, 2006. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved November 1, 2009.

- ^ "Report on Iraqi Chemical Munitions". June 21, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2006.

- ^ Dafna Linzer (June 23, 2006). "Lawmakers Cite Weapons Found in Iraq". The Washington Post.

- ^ Juana Summers (May 17, 2011). "Rick Santorum: John McCain wrong on torture". Politico. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c Raffaele, Martha (October 27, 2006). "Santorum: Casey lacking on security". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ Summers, Juana (May 17, 2011). "Rick Santorum: John McCain wrong on torture". Politico.

- ^ "Santorum: McCain Doesn't Understand Interrogation". Fox News. May 18, 2011. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved May 13, 2019.

- ^ "Santorum Hits President on Afghanistan Withdrawal Timeline – ABC News". ABC News. March 12, 2012. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Siegel, Elyse (September 22, 2011). "GOP Debate: Republican Presidential Candidates Face Off In Florida (Live Updates)". HuffPost. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ a b c Hefling, Kimberly (July 21, 2006). "Santorum says Iran at center of world's conflict". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ a b O'Toole, James (April 18, 2003). "Santorum trying again on Syria sanctions bill". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Bonnie Squires; Dan Loeb (September 18, 2006). "Rick Santorum On Iran: His record does not match his rhetoric". Philadelphia Jewish Voice. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- ^ Rick Santorum (December 6, 2007). "The Elephant in the Room | Put aside politics to confront Iran". Philly.com. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Ball, Molly (January 2, 2012). "Who Is Rick Santorum?". The Atlantic Wire. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ McKinnon, Mark (August 12, 2009). "Santorum Is Dangerous". The Daily Beast. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Michael Sokolove (May 22, 2005). "The Believer". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ^ a b Joyner, James (January 5, 2007). "Santorum Ouster Means End of Senate Candy Desk". Outside the Beltway.

- ^ a b Toeplitz, Shira (February 13, 2011). "Mark Kirk: Senate candy man". Politico.

- ^ Maeve Reston (January 26, 2005). "Santorum focusing on re-election to Senate, not White House run". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007.

- ^ Williams, Juan (January 11, 2006). "The K Street Project and Jack Abramoff". NPR. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c Marcus Stern and Kristina Cooke (January 5, 2012). "Rivals set to pounce on Santorum's past". Reuters. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ Dan Eggen; Carol D. Leonnig ( January 5, 2012). "Santorum plays down long history as Washington insider". The Washington Post.

- ^ McIntire, Mike; Luo, Michael (January 6, 2012). "After Santorum Left Senate, Familiar Hands Reached Out". The New York Times.

- ^ Santorum and the Lobbyists 'K Street? K Street? Never heard of it' The Philadelphia Inquirer January 29, 2006

- ^ a b Reston, Maeve (November 15, 2005). "Casey chides Santorum on lobbying ethics". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Archived from the original on January 30, 2016. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ a b Miller, Jeff (January 26, 2006). "Santorum denies working with K Street project". The Morning Call. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- ^ Josh Hicks (January 9, 2012). "Rick Santorum and the K Street Project". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Senate: Casey by 23 Santorum Remains Most Vulnerable Incumbent". Rasmussen Reports. May 31, 2006.

- ^ Naftali Bendavid (January 7, 2012). "An Old Loss Dogs Surging Santorum". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Cooke, Kristina (March 5, 2012). "Special report: Santorum's wins and self-inflicted wounds". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 23, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Jerry Bowyer (October 10, 2006). "Outside Santorum's Sanctum". New York Sun. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- ^ Stephen Moore (April 15, 2004). "Santorum's Shame". National Review.