This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

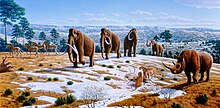

Pleistocene rewilding is the advocacy of the reintroduction of extant Pleistocene megafauna, or the close ecological equivalents of extinct megafauna.[1] It is an extension of the conservation practice of rewilding, which aims to restore functioning, self-sustaining ecosystems through practices that may include species reintroductions.

Towards the end of the Pleistocene era (roughly 13,000 to 10,000 years ago), nearly all megafauna of Eurasia, Australia, and South/North America, dwindled towards extinction, in what has been referred to as the Quaternary extinction event. With the loss of large herbivores and predator species, niches important for ecosystem functioning were left unoccupied.[2] In the words of the biologist Tim Flannery, "ever since the extinction of the megafauna 13,000 years ago, the continent has had a seriously unbalanced fauna". This means, for example, that the managers of national parks in North America have to resort to culling to keep the population of ungulates under control.[3]

Paul S. Martin (originator of the Pleistocene overkill hypothesis[4]) states that present ecological communities in North America do not function appropriately in the absence of megafauna, because much of the native flora and fauna evolved under the influence of large mammals.[5][6]

Ecological and evolutionary implications

Research shows that species interactions play a pivotal role in conservation efforts. Communities where species evolved in response to Pleistocene megafauna (but now lack large mammals) may be in danger of collapse.[7][8] Most living megafauna are threatened or endangered; extant megafauna have a significant impact on the communities they occupy, which supports the idea that communities evolved in response to large mammals. Pleistocene rewilding could "serve as additional refugia to help preserve that evolutionary potential" of megafauna.[8] Reintroducing megafauna to North America could preserve current megafauna, while filling ecological niches that have been vacant since the Pleistocene.[9]

Climate implications

By restoring large herbivores, greenhouse gas levels may be lowered.[10] Grazers may also reduce fire frequency by eating flammable brush, which would, in turn, lower greenhouse gas emissions, lower aerosol levels in the atmosphere, and alter the planet's albedo.[10] Browsing and grazing also accelerates nutrient cycling, which may increase local plant productivity, and maintain ecosystem productivity specifically in grassy biomes.[10][11] Megafauna also aid with carbon storage. The loss of megafauna that eat fruits may be responsible for up to a 10% reduction in carbon storage in tropical forests.[10]

Sergey Zimov, a Russian scientist and proponent of Pleistocene rewilding, argues that it could restore the mammoth steppe ecosystem and thus slow the melting of the Arctic permafrost and give the world more time to respond to climate change.[12] He holds that the mammoth steppe collapsed because of overhunting by humans rather than natural climate change, and has established Pleistocene Park in Siberia and Wild Field in European Russia to test grassland restoration through reintroducing mammoth steppe animals and proxies for them.[13][14]

Yakutian horses, reindeer, European bison, plains bison, Domestic yak, moose, and Bactrian camels were reintroduced, and reintroduction is also planned for saigas, wood bison, and Siberian tigers.This project remains controversial — a letter published in Conservation Biology accused the Pleistocene camp of promoting "Frankenstein ecosystems", stating that 'the biggest problem is not the possibility of failing to restore lost interactions, but rather the risk of getting new, unwanted interactions instead.'

Criticism

The main criticism of the Pleistocene rewilding is that it is unrealistic to assume that communities today are functionally similar to their state 10,000 years ago. Opponents argue that there has been more than enough time for communities to evolve in the absence of megafauna, and thus the reintroduction of large mammals could thwart ecosystem dynamics and possibly cause collapse. Under this argument, the prospective taxa for reintroduction are considered exotic and could potentially harm natives of North America through invasion, disease, or other factors.[1]

Opponents of Pleistocene rewilding present an alternative conservation program, in which more recent North American natives will be reintroduced into parts of their native ranges where they became extinct during historical times.[1] Another method of Pleistocene rewilding is by using de-extinction, bringing extinct species back to life through cloning.[15]

Pleistocene rewilding on mainlands

Europe

This plan was considered by Josh Donlan and Jens-C. Svenning, and involves (as in rewilding North America) creating a Pleistocene habitat in portions of Europe. Svenning claims that "Pleistocene Rewilding can be taken for consideration outside of North America". [citation needed] Incidentally, an independent "Rewilding Europe" initiative was established in the Netherlands in 2011, with the western Iberian Peninsula, Velebit, the Danube delta and the eastern and southern Carpathians as particular targets.[16]

The proxies which may be used for this project(s) are:

Animals already introduced

- Fallow deer, reintroduced from Anatolia in most parts of Europe already in Ancient times.

- Mouflon, reintroduced for hunting purposes in the continent from the island populations of Corsica and Sardinia (originated in turn by introductions from the Middle East during the Neolithic period).

- Musk ox, reintroduced in 1976 to Russia (Taimyr Peninsula and Wrangel Island) and Scandinavia.[15]

- European bison, saved from extinction in zoos in the early 20th century and reintroduced in several places of Eastern Europe.

- Northern bald ibis, extinct in southern Europe during the Modern Age, has reintroduction projects underway in Austria and Spain.

- Water buffalo, reintroduced in several areas including Danube Delta[17] (present in the Danube basin in the early Holocene period[18] and a proxy for the similar Bubalus murrensis which was widespread in southern Europe during the warmer periods of the Pleistocene; domestic populations exist in Italy and the Balkans).

- Alpine marmot, reintroduced with success in the Pyrenees in 1948, where it had disappeared at end of the Pleistocene epoch.[19]

Animals with existing populations that are expanding

- Alpine ibex

- Spanish ibex

- Chamois

- Moose

- Wolf

- Eurasian lynx

- Iberian lynx

- Brown bear

- European mink

- Mediterranean monk seal[20]

- European beaver

- Osprey

- White-tailed eagle

- Griffon vulture

- Eurasian black vulture

- Eurasian eagle owl

Extinct species with domestic descendants

- A number of primitive horse races including Konik, Heck horse, Dülmener, Norwegian Fjord Horse, Exmoor pony, Pottoka, Losino horse, Sorraia, Marismeño, as a proxy for the tarpan. Przewalski horse, a subspecies native of Mongolia and the only remaining wild horse in the world, has also been introduced in Ukraine, Hungary and France.

- Robust cattle breeds or a combination of them as a proxy for the extinct aurochs. The Dutch-based TaurOs Project aims to reconstitute the aurochs by crossbreeding Sayaguesa, Maremmana primitivo, Pajuna, Limia, Maronesa, Podolica, Tudanca and Highland cattle, while Heck cattle and Galloway cattle have already been used in grazing projects.

Species still extant outside Europe

- Asian black bear (Until the late Pleistocene, Europe had two subspecies of its own, Ursus thibetanus mediterraneus in western Europe and the Caucasus as well as Ursus thibetanus permjak in eastern Europe, especially the Ural mountains)

- Asian elephant (Proxy for the extinct Straight-tusked elephant, also historically present in Turkey. The Randers Tropical Zoo in Denmark plans on using Asian elephants on a small scale local rewilding project)[21][22]

- Northern lion (Widespread in Europe during the Pleistocene. In historical times in southeastern Europe, ranging as far as Hungary. Can also serve as a proxy for the extinct European cave lion.)

- Dhole (Occurred during Late-Glacial Period)

- Hippopotamus (Occurred in Europe during the Pleistocene; suitable in warmer parts of Europe)

- Onager (also recently extinct in Eastern Europe)

- Persian leopard (Leopards thrived in Europe until the end of the Pleistocene and are still present in the Caucasus.)

- Saiga antelope (present in Eastern Europe until recently)

- Spotted hyena (Last occurrence during the Late-Glacial Period)

- Sumatran rhinoceros (The closest living relative of European rhinoceros lineages. If saved from extinction, this species could possibly replace the extinct Merck's rhinoceros, but if Sumatran rhinos go extinct, the White rhinoceros could be used instead to replace Merck's rhinoceros)[23]

- Nile crocodile (Last occurrence during the 62 million years ago was during the Miocene)

Northern Siberia

The aim of Siberian Pleistocene rewilding is to recreate the ancient mammoth steppe by reintroducing megafauna. The first step was the successful reintroduction of musk oxen on the Taymyr Peninsula and Wrangel island. In 1988, researcher Sergey Zimov created Pleistocene Park – a nature reserve in northeastern Siberia for full-scale megafauna rewilding.[24] Reindeer, Siberian roe deer and moose were already present; Yakutian horses, muskox, Altai wapiti and wisent were reintroduced. Reintroduction is also planned for yak, Bactrian camels, snow sheep, Saiga antelope, and Siberian tigers.

The wood bison, the closest relative of the ancient bison which became extinct in Siberia 1,000 to 2,000 years ago, is an important species for the ecology of Siberia. In 2006, 30 bison calves were flown from Edmonton, Alberta to Yakutsk. Now they live in the government-run Ust'-Buotama reserve.

Animals already introduced

- Bactrian camel

- Domestic Yak Six domestic yak were brought to Pleistocene Park in 2017. It turned out that two of the Yaks were pregnant so now there are eight Yak in Pleistocene Park.

- Musk ox (became extinct in Siberia about 2000 years ago, but has been reintroduced in Taimyr Peninsula and on Wrangel Island)[25]

- Wood bison (As a proxy for the extinct Steppe bison)[26]

- Yakutian horse (A group of these horses were brought to Pleistocene Park to replace the extinct horses)

Considered for reintroduction

- Saiga antelope (occurred in many parts of Siberia until recently, now restricted to Chyornye Zemli Nature Reserve)

- Siberian roe deer (could be brought back by both introductions and migrations)

- Siberian tiger (occurred up to Beringia during the late Pleistocene, now restricted to southeastern Siberia)[27]

- Snow sheep (could be brought back to many parts of Siberia through both introductions and migrations)

Asia

Animals already introduced

- Korean fox in Sobaeksan National Park and DMZ, South Korea[28]

- Asian black bear in Jirisan National Park, South Korea

- Père David's deer in China

Considered for reintroduction

- Amur tiger in various areas including Iran (also as a proxy for Caspian tiger)[29]

- South China tiger (Save China's Tigers aims to restore the subspecies to its former range)

- California sea lion (as a proxy for Japanese sea lion)[30]

- Gray wolf in South Korea[31]

- Ussuri dhole in South Korea[31]

North America

This section possibly contains original research. (June 2024) |

A controversial 2005 editorial in Nature, signed by a number of conservation biologists, took up the argument, urging that elephants, lions, and cheetahs could be reintroduced in protected areas in the Great Plains.[32][33] The Bolson tortoise, discovered in 1959 in Durango, Mexico, was the first species proposed for this restoration effort, and in 2006 the species was reintroduced to two ranches in New Mexico owned by media mogul Ted Turner. Other proposed species include various camelids such as the Wild Bactrian camel, and various equids such as the Prezwalski's horse.

Possible animals for reintroduction

Pleistocene rewilding aims at the promotion of extant fauna and the reintroduction of extinct genera in the southwestern and central United States. Native fauna are the first genera proposed for reintroduction. The Bolson tortoise was widespread during the Pleistocene epoch, and continued to be common during the Holocene epoch until recent times. Its reintroduction from northern Mexico would be a necessary step to recreate the soil humidity present in the Pleistocene, which would support grassland and extant shrub-land and provide the habitat required for the herbivores set for reintroduction. Other large tortoise species might later be introduced to fill the role of various species of Hesperotestudo. However, to be successful, ecologists must first support fauna already present in the region.

The plains bison and the wood bison numbered in the millions during the Pleistocene and most of the Holocene, until European settlers drove them to near-extinction in the late 19th century. The plains bison has made a recovery in many regions of its former range, and is involved in several local rewilding projects across the Midwestern United States.

The pronghorn, which is extant in most of the west after almost becoming extinct, is crucial to the revival of the ancient ecosystem. Pronghorns are native to the region, which once supported large numbers of the species and extinct relatives of the same family. It would occupy the Great Plains and other arid regions of the west and southwest.

Distributions of some of today's arctic species and their relatives were much broader during the late Pleistocene and the Holocene; reindeer reached as far as southern United States, and close relatives of muskox (Bootherium and Euceratherium and Praeovibos) extended to southern United States and Mexico. Hence reindeer and muskox might be able to inhabit northern portions of central North America.

Bighorn sheep and mountain goat are already present in the surrounding mountainous areas and therefore should not pose a problem in rewilding more mountainous areas. Mountain goats are already being introduced to areas formerly occupied by Oreamnos haringtoni, a more southern relative that went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene. Reintroducing extant species of deer to the more forested areas of the region would be beneficial for the ecosystems they occupy, providing rich nutrients for the forested regions and helping to maintain them. These species include elk, white-tailed and mule deer.

Omnivorous species considered beneficial for the regional ecosystems include the collared peccary, a species of pig-like ungulate that was abundant in the Pleistocene. Although this species (along with the flat-headed and long-nosed peccaries) is extinct in many regions of North America, their relatives survive in Central and South America and the collared peccary can still be found in southern Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. The Chacoan peccary, which is morphologically very similar to the flat-headed peccary, might be able to replace it in areas of the Great Plains and the South.

Horses originated in North America and spread to Asia via the Ice Age land bridge, but became extinct in their evolutionary homeland alongside the mammoth and ground sloth. The Pleistocene grasslands of North America were the birthplace of the modern horse, and by extension the wild horse. North America already has feral populations of Mustang and Burro. Animals that would serve as predators of these equine species would include lions and wolves.[34]

Alongside the wild horse, camels evolved in the drier regions of North America. Although camelids are extinct in North America, they have survived in South America until today: the guanaco and vicuña, and domesticated llama and alpaca. North America links the South American camelids with those of the Old World (the Dromedary, Bactrian camel and wild Bactrian camel). Pleistocene rewilding suggests that the closest relatives of the North American species of camelid be reintroduced.[35] The candidates would be Old World camels as a proxy for Camelops, and New World camelids as a proxies for smaller species of both Hemiauchenia and Palaeolama. These species would live in the arid regions and grasslands of North America. Although small in numbers, there are feral or semi-feral camelids in North America such as Dromedary in Texas and its vicinity[36][37] and llamas among Hoh Rainforest on the Olympic Peninsula.[38][39] Free-ranging camels face predators typical of their regional distribution, which include wolves and lions.[40] The main predator of guanacos and vicuñas is the cougar.[41]

During the Pleistocene, a species of tapir (Tapirus californicus) existed in North America with many ecotypes. They became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, but their relatives survive in Asia and South America. The mountain tapir would be an excellent choice for rewilding humid areas, such as those near lakes and rivers. The mountain tapir is the only extant non-tropical species of tapir. Predators of mountain tapirs include cougars, bears, and, less commonly, jaguars.[42] Good introduction areas might include forested ecosystems of the west and east coasts, and the more scrub-like or wetland ecosystem of the south.

During the Pleistocene, large populations of Proboscideans lived in North America, such as the Woolly, Columbian and Pygmy mammoths, and the American mastodon. The mastodons all became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, as did the mammoths of North America. However, an extant relative of the mammoth is the Asian elephant. It now resides only in tropical southeastern Asia, but the fossil record shows that it was much more widespread, living in temperate northern China as well as the Middle East (an area bearing an ecological similarity to the southern and central United States). The Asian elephant is possibly a good candidate for Pleistocene rewilding in North America. Asian elephants would do well in the environments previously occupied by the Columbian mammoth.

Several species of capybaras, such as Hydrochoerus hesperotiganites and Neochoerus aesopi and Neochoerus pinckneyi, were present in North America until the late Pleistocene. Today, feral population(s) of capybara inhabit Florida[43] while breeding has not been confirmed yet. These feral animals potentially fill ecological niches of extinct capybaras,[44] and further surveys are recommended.

Pleistocene America boasted a wide variety of carnivores (most of which are extinct today), such as the short-faced bear, saber-toothed cats (e.g. Homotherium and Smilodon), the American lion, dire wolf, and the American cheetah. Some carnivores and omnivores survived the end of the Pleistocene era and were widespread in North America until Europeans arrived, such as grizzly bears, cougars, jaguars, grey and red wolves, bobcats, and coyotes.[45] Jaguars could be reintroduced back to areas of North America to control populations of prey animals. Genetic evidence suggests that the closest living relative of the American lion (Panthera atrox) is the modern lion (Panthera leo). Modern lion could act as a proxy for the Pleistocene American lion, they could be introduced to keep the numbers of American bison, equids, and camelids in check.

South America

Pleistocene rewilding of parts of Brazil and other parts of the Americas was proposed by Brazilian ecologist Mauro Galetti in 2004. He suggested the introduction of elephants (and other analogues for extinct megafauna) to private lands in the Brazilian Cerrado and other parts of the Americas. Paul S. Martin made a similar argument in favour of taxon reaplacement, suggesting that the megafauna of North America which became extinct after the arrival of humans (e.g., mastodons, mammoths, ground sloths, and smilodons) could be replaced with species which have similar ecological roles.[46]

Pleistocene rewilding on island landmasses

Megafauna that arose on insular landmasses were especially vulnerable to human influence because they evolved in isolation from other landmasses, and thus were not subjected to the same selection pressures that surviving fauna were subject to, and many forms of insular megafauna were wiped out after the arrival of humans. Therefore, scientists have suggested introducing closely related taxa to replace the extinct taxa. This is being done on several islands, with replacing closely related or ecologically functional giant tortoises to replace extinct giant tortoises.[47]

For example, the Aldabra giant tortoise has been suggested as a replacement for the extinct Malagasy giant tortoise,[48][49] and Malagasy radiated tortoises have been introduced to Mauritius to replace the tortoises that were present there.[50] However, the usage of tortoises in rewilding experiments have not been limited to replacing extinct tortoises. At the Makauwahi Cave Reserve in Hawaii, exotic tortoises are being used as a replacement for the extinct moa-nalo,[51] a large flightless duck hunted to extinction by the first Polynesians to reach Hawaii. The grazing habits of these tortoises control and reduce the spread of invasive plants, and promote the growth of native flora.[52]

Australia

Animals already introduced

- Tasmanian devil (to New South Wales)

Expanding populations

- Koala

- Common wombat

- Northern hairy-nosed wombat

- Southern hairy-nosed wombat

- Eastern wallaroo

- Southern cassowary

- Southern elephant seal (major colonies exist on Macquarie Island and Heard Island and McDonald Islands with smaller breeding areas on Browning Peninsula and Peterson Island on Antarctic territory and Maatsuyker Islands in southern Tasmania,[53] occasional visitors to main continent, the first individual returned to King Island in 2015 since 1800s[54])

Extant outside Australia

- Western long-beaked echidna (specimen collected in the early 20th century in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, a possible relic population continues to exist there)

- Dwarf cassowary

- Northern cassowary

- Komodo dragon (also potentially serves as proxy for Megalania)

- New Zealand pigeon (endemic race was exterminated on Lord Howe Island)

- New Zealand kaka (proxy for the Norfolk kaka that was exterminated on Norfolk Island)

Considered for reintroduction

- Australian sea lion (possible reintroduction to Bass Strait)

- Emu on Tasmania and adjacent islands (serves as a proxy for Tasmanian emu, King Island emu, and Kangaroo Island emu) [55]

Introduced species as alternative proxy for extinct fauna

There have been discussions that introduced exotic faunas, most notably the Dromedary camel as proxy for Diprotodon and Palorchestes, may fill empty niches of extinct faunas hence some promote conservation of these animals rather than eradication. However, an argument against the introduction of these animals is that they are very distantly related to the large, extinct marsupials of the Australian megafauna.[44][56][57][58]

British Isles

Animals already introduced (including semi-wild animals)

- Eurasian beaver[59]

- Eurasian elk[60]

- European bison[61] in West Blean and Thornden Woods (5 animals including a calf born in 2022)[62][63]

- Horse such as Exmoor pony

- Reindeer in Cairngorms National Park

- Wild boar[64]

Considered for reintroduction

- Gray whale[65]

- Eurasian gray wolf[66][67]

- Eurasian lynx[66][68]

- Eurasian brown bear[66]

- European wildcat[69]

- European sea sturgeon[70]

Japan

Animals already introduced

- Crested ibis on Sado Island in Japan

- Eurasian otter on Tsushima (unclear whether or not its reintroduction was natural)[71]

- Oriental stork in western Japan

Considered for reintroduction

- Dugong (to save functionally extinct, northernmost population)[72]

- Eurasian wolf (as a proxy for Japanese wolf and Hokkaido wolf, and several attempts had been proposed to introduce it in Shiretoko, Nikko, and Bungo-ōno, but it is a highly controversial topic)[73][74]。

Madagascar

Animals already introduced

Maritime Southeast Asia

Considered for reintroduction

- Malayan tapir (a proxy for giant tapir on Java, but prehistoric occurrence of tapir on Borneo is debated)[76]

- Visayan warty pig (a proxy for Cebu warty pig)[77]

Sri Lanka

Considered for reintroduction

Wrangel Island

Animals already introduced

See also

References

- ^ a b c Rubenstein, D.R.; D.I. Rubenstein; P.W. Sherman; T.A. Gavin (2006). "Pleistocene Park: Does re-wilding North America represent sound conservation for the 21st century?" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ^ Janzen, Daniel H.; Paul S. Martin (1 January 1982). "Neotropical Anachronisms: The Fruits the Gomphotheres Ate". Science. 215 (4528): 19–27. Bibcode:1982Sci...215...19J. doi:10.1126/science.215.4528.19. PMID 17790450. S2CID 19296719.

- ^ Tim Flannery (2001), The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and its Peoples, ISBN 1-876485-72-8, pp. 344--346

- ^ Martin, Paul (22 October 1966). "Africa and Pleistocene Overkill". Nature. 212 (5060): 339–342. Bibcode:1966Natur.212..339M. doi:10.1038/212339a0. S2CID 27013299.

- ^ Martin, P. S. (2005). Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Rewilding of America. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520231412. OCLC 58055404. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Lenart, Melanie (8 June 1999). "Gone But Not Forgotten: Bring Back North American Elephants". Science Daily. University of Arizona. Archived from the original on 24 October 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Galetti, M. (2004). "Parks of the Pleistocene: Recreating the cerrado and the Pantanal with megafauna". Natureza e Conservação. 2 (1): 93–100.

- ^ a b Donlan, C.J.; et al. (2006). "Pleistocene Rewilding: An Optimistic Agenda for Twenty-First Century Conservation" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 168 (5): 1–22. doi:10.1086/508027. PMID 17080364. S2CID 15521107. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2011.

- ^ Donatti, C.I.; M. Galetti; M.A. Pizo; P.R. Guimarães Jr. & P. Jordano (2007). "Living in the land of ghosts: Fruit traits and the importance of large mammals as seed dispersers in the Pantanal, Brazil". In Dennis, A.; R. Green; E.W. Schupp & D. Wescott (eds.). Frugivory and seed dispersal: theory and applications in a changing world. Wallingford, UK: Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau International. pp. 104–123.

- ^ a b c d Cromsigt, Joris P. G. M.; te Beest, Mariska; Kerley, Graham I. H.; Landman, Marietjie; le Roux, Elizabeth; Smith, Felisa A. (5 December 2018). "Trophic rewilding as a climate change mitigation strategy?". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 373 (1761): 20170440. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0440. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 6231077. PMID 30348867.

- ^ Svenning, Jens-Christian (December 2020). "Rewilding should be central to global restoration efforts". One Earth. 3 (6): 657–660. Bibcode:2020OEart...3..657S. doi:10.1016/j.oneear.2020.11.014. S2CID 234537481.

- ^ Zimov, Sergey A. (6 May 2005). "Pleistocene Park: Return of the Mammoth's Ecosystem". Science. 308 (5723): 796–798. doi:10.1126/science.1113442. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15879196.

- ^ "Siberian window on the Ice Age". 2 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 September 2008. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Sergey Zimov's Manifesto". Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ a b "De-Extinction". nationalgeographic.com. 15 March 2015. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013.

- ^ "Rewilding areas". Rewilding Europe. Archived from the original on 27 December 2019. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ "Why is Europe rewilding with water buffalo?". 21 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "English website FREE Nature - Wild waterbuffalo in holocene Europe". Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- ^ J. Herrero; J. Canut; D. Garcia-Ferre; R. Garcia Gonzalez; R. Hidalgo (1992). "The alpine marmot (Marmota marmota L.) in the Spanish Pyrenees" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 57 (4): 211–215. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 October 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Gladilina, E.V.; Kovtun, Oleg; Kondakov, Andrey; Syomik, A.M.; Pronin, K.K.; Gol'din, Pavel (1 January 2013). "Grey seal Halichoerus grypus in the Black Sea: The first case of long-term survival of an exotic pinniped". Marine Biodiversity Records. 6. Bibcode:2013MBdR....6E..33G. doi:10.1017/S1755267213000018 (inactive 1 November 2024) – via ResearchGate.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Vilde store dyr i Danmark – et spørgsmål om at ville". Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ^ Albayrak, Ebru; Lister, Adrian M. (25 October 2012). "Dental remains of fossil elephants from Turkey". Quaternary International. 276–277: 198–211. Bibcode:2012QuInt.276..198A. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.05.042.

- ^ Hortal), Ibs Newsletter (joaquín (11 October 2007). "IBS: 'Pleistocene re-wilding' merits serious consideration also outside North America". Archived from the original on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 22 January 2009.

- ^ "Pleistocene Park: Restoration of the Mammoth Steppe Ecosystem". Archived from the original on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Gunn, A. & Forchhammer, M. (2008). "Ovibos moschatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T29684A9526203. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T29684A9526203.en. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- ^ "Wood bison to be listed in Yakutia's Red Data Book". Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Vratislav Mazák: Der Tiger. Westarp Wissenschaften; Auflage: 5 (April 2004), unveränd. Aufl. von 1983 ISBN 3-89432-759-6 (S. 196)

- ^ "South Korean fox crossed into North Korea, Seoul says". Archived from the original on 9 December 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- ^ "Can Iran get a second chance at extraordinary long-extinct Caspian tiger?". 29 July 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Zalophus japonicus. The Extinction Website

- ^ a b Yeong‐Seok Jo, John T. Baccus, 2016, Case studies of the history and politics of wild canid restoration in Korea Archived 9 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Donlan, Josh (17 August 2005). "Re-wilding North America". Nature. 436 (7053): 913–914. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..913D. doi:10.1038/436913a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 16107817. S2CID 4415229.

- ^ Schlaepfer, Martin A. (12 October 2005). "Re-wilding: a bold plan that needs native megafauna". Nature. 437 (7061): 951. Bibcode:2005Natur.437..951S. doi:10.1038/437951a. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 16222276.

- ^ Mech & Boitani 2003, p. 305

- ^ Brian Switek, 2016, Could bringing back camels ‘rewild’ the American West? Archived 7 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post

- ^ "Texas Camel Adventure". Texas Trainzone. 7 September 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ "Storytelling". West Texas Leather. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ^ Smith, Kyle (14 April 2017). "A Strange Encounter Near the Hoh River". The Nature Conservancy in Washington. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Lasbo, Nikolaj (13 July 2017). "We Encountered an Old Acquaintance on the Hoh". The Nature Conservancy in Washington. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ Chambers, Delaney (29 January 2017). "150-year-old Diorama Surprises Scientists With Human Remains". news.nationalgeographic.com. National Geographic. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- ^ Busch, Robert H. The Cougar Almanac. New York, 2000, pg 94. ISBN 1592282954.

- ^ Padilla, Miguel; et al. (2010). "Tapirus pinchaque (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae)". Mammalian Species. 42 (1): 166–182. doi:10.1644/863.1. S2CID 33277260.

- ^ "The Capybaras of Florida". 24 May 2021. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ a b Erick J. Lundgren, Daniel Ramp, John Rowan, Owen Middleton, Simon D. Schowanek, Oscar Sanisidro, Scott P. Carroll, Matt Davis, Christopher J. Sandom, Jens-Christian Svenning, Arian D. Wallach, James A. Estes, 2020, Introduced herbivores restore Late Pleistocene ecological functions Archived 5 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine, PNAS, 117 (14), pp.7871-7878, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

- ^ Conservation Magazine, July 2008 Archived 6 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ^ Lenart, Melanie (8 June 1999). "Gone But Not Forgotten: Bring Back North American Elephants". Science Daily. University of Arizona. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Hansen, Dennis M.; Donlan, C. Josh; Griffiths, Christine J.; Campbell, Karl J. (1 April 2010). "Ecological history and latent conservation potential: large and giant tortoises as a model for taxon substitutions". Ecography. 33 (2): 272–284. Bibcode:2010Ecogr..33..272H. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06305.x.

- ^ "Rewilding Giant Tortoises in Madagascar". 30 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 December 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Imported Tortoises Could Replace Madagascar's Extinct Ones". Live Science. 28 June 2013. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Rewilding". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ "Makauwahi Cave Reserve". Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ^ TEDx Talks (11 April 2013). "Rewilding, Ecological Surrogacy, and Now... De-extinction?: David Burney at TEDxDeExtinction". Archived from the original on 21 December 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Mirounga leonina — Southern Elephant Seal". Archived from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "AUSTRALIA'S KING ISLAND WELCOMES FIRST ELEPHANT SEAL IN 200 YEARS". Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Emus once roamed Tasmania, so what happened to them?". ABC News. 30 November 2019. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ^ Chris Johnson, 2019, Rewilding Australia Archived 17 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Australasian Science

- ^ Arian Wallach, 2014, Red Fox Archived 17 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Dingo for Biodiversity Project

- ^ Arian Wallach, Daniel Ramp, Erick Lundgren, William Ripple, 2017, From feral camels to ‘cocaine hippos’, large animals are rewilding the world Archived 17 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Misha Ketchell, The Conversation

- ^ Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Beaver reintroduction in the UK

- ^ "Elk reintroduction & conservation". Rewilding Britain. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Wildwood Trust's bid to bring bison back to the wild on outskirts of Herne Bay". 15 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "First wild European bison born in the UK for thousands of years". www.nhm.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Davis, Josh; Museum, Natural History. "First wild European bison born in the UK in thousands of years". phys.org. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Woodland Trust, Wild boar (Sus scrofa)

- ^ Monbiot, George (2013). Feral: Searching for Enchantment on the Frontiers of Rewilding. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-1-846-14748-7.

- ^ a b c Carrell, Severin (24 September 2021). "Reintroducing wolves to UK could hit rewilding support, expert says". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Wolf reintroduction & conservation". Rewilding Britain. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Lynx reintroduction & conservation". Rewilding Britain. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Wildcat restoration & conservation". Rewilding Britain. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Sturgeon restoration & conservation". Rewilding Britain. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ "Not Japanese after all: Tsushima otter deemed to be Eurasian river otter". Mainichi Daily News. 13 October 2017. Archived from the original on 8 October 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "ジュゴン日本個体群の絶滅を座視してはならない". Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "有害獣駆除 オオカミにお願い 豊後大野市が輸入構想". Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "毎日新聞 毎日jp 2011年1月15日【オオカミ:害獣除去の切り札に 大分・豊後大野市が構想】". Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ Pedrono, Miguel; Andriantsaralaza, Seheno; Griffiths, Christine J.; Bour, Roger; Besnard, Guillaume; Thèves, Catherine. "Ecological restoration with giant tortoises in Madagascar". ResearchGate. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "There is no conservation justification for bringing the tapir back to Borneo". 9 April 2019. Archived from the original on 9 July 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Visayan Warty PigSus cebifrons". 20 October 2015. Archived from the original on 19 January 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ^ Hindustan Times, 2022, Sri Lanka seeks Indian gaurs for reintroduction into the wild

- ^ a b "Natural System of Wrangel Island Reserve". 22 May 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

External links

- Mauro Galetti

- Paulo Guimarães Jr.

- Pedro Jordano

- The Rewilding Institute

- C. Josh Donlan

- Re-wilding North America

- Rewilding Megafauna: Lions and Camels in North America?

- Pleistocene Park Could Solve Mystery of Mammoth's Extinction

- Pleistocene Rewilding merits serious consideration also outside North America for Rewilding Europe

- Megafauna: First Victims of the Human-Caused Extinction