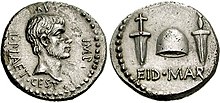

The gens Plaetoria was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. A number of Plaetorii appear in history during the first and second centuries BC, but none of this gens ever obtained the consulship. Several Plaetorii issued denarii from the late 70s into the 40s, of which one of the best known alludes to the assassination of Caesar on the Ides of March, since one of the Plaetorii was a partisan of Pompeius during the Civil War.[2]

Origin

editChase classifies the nomen Plaetorius among those gentilicia which were either of Roman origin, or which at least cannot be shown to have originated anywhere else, implying that the name is apparently of Latin derivation. Some scholars have suggested that the Plaetorii hailed from the ancient city of Tusculum in Latium.[3][4]

Praenomina

editThe main praenomina of the Plaetorii were Marcus, Gaius, and Lucius, the three most common names throughout Roman history.

Branches and cognomina

editThe only distinct family of the Plaetorii under the Republic bore the cognomen Cestianus, probably indicating that they were originally adopted from the Cestii, a family of Praeneste.[4] Their coins allude both to their name, depicting an athlete holding a cestus, and to a Praenestine origin, depicting Sors, the god of luck, associated with the renowned Praenestine oracle.[5][6]

Members

edit- This list includes abbreviated praenomina. For an explanation of this practice, see filiation.

- Marcus Plaetorius, tribune of the plebs in an uncertain year. He carried a plebiscite that established what attendants the praetor peregrinus might have. The office of praetor peregrinus was established in the late 240s BC.[7][8][9][10][11]

- Gaius Plaetorius,[i] one of the commissioners appointed to establish a colony at Croton in 194 BC.[12]

- Plaetorius, tribune of the plebs before 192 BC. Cicero mentions a lex Plaetoria[ii] that protected minors and young men from fraud. Since Plautus refers to such legislation, this law would seem to predate 191 BC.[13][14][15][16]

- Plaetorius, tribune of the plebs before 175 BC, carried a law under which an altar was dedicated to Verminus by Aulus Postumius Albinus, the consul of 180, when he was duumvir, and another altar found in the Largo Argentina.[17]

- Gaius Plaetorius, sent as one of three ambassadors to Gentius of Illyria to protest attacks on allies of Rome. He might be the same person as the Gaius Plaetorius who was appointed to establish a colony at Croton in 194.[18][19]

- Lucius Plaetorius, a senator mentioned in 129 BC.[20]

- Marcus Plaetorius, a senator put to death on Sulla's orders in 82 BC, along with Venuleius. Münzer distinguishes him from the Marcus Laetorius who accompanied Gaius Marius into exile in 88 BC, but the names Laetorius and Plaetorius often create textual difficulties.[21][22][23][24]

- Lucius Plaetorius L. f. (Cestianus?), quaestor circa 74–72 BC, or possibly as late as 66, when Cicero refers to him as a senator. Crawford dates his coinage to 74.[25][26]

- Marcus Plaetorius Cestianus, praetor circa 64 BC, and subsequently governor of Macedonia. He is probably the same Marcus Plaetorius who served under Publius Cornelius Lentulus Spinther in Cilicia in 55.[iii][27][28][29][30]

- Gaius Plaetorius, quaestor under Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus in Pontus in 48 BC.[31][32]

- Plaetorius Rustianus, a senator in 46 BC, was a leader among Pompeius' forces in Africa. He died at Hippo.[33][34]

- Lucius Plaetorius L. f. Cestianus, quaestor or proquaestor under Brutus in 42.[35]

- Aulus Plaetorius Nepos, a senator, was a friend of Hadrian, and one of those whom the emperor considered appointing to succeed him.[36]

Footnotes

edit- ^ Or Laetorius.

- ^ Plaetoria, Broughton contra RE, Supb. 7.398, which has Laetoria.

- ^ Cestianus is the most extensively documented of the Republican Plaetorii, but the dating of his offices is problematic. Crawford places his coinage as a triumvir monetalis in 69, but he was quaestor sometime before he prosecuted Fonteius in 69 BC (Cicero, Pro Fonteio, 1), and in the late Republic, a young man usually served as a moneyer before a quaestorship; see Syme, "The Sons of Crassus", in Latomus, vol. 39 (1980), pp. 403–408.</ref> Cestianus was curule aedile most likely in 67 (Cicero, Pro Cluentio, 126), when he also issued coinage. In 66, he was iudex for a quaestio de sicariis (Cicero, Pro Cluentio, 147, see also 126). Broughton conjectures the date of his praetorship based on assigning his service as a iudex to 66, and the gap that leaves room for his name on the Fasti of Macedonia. He succeeded Lucius Manlius Torquatus as governor of Macedonia in 63, and was followed by Gaius Antonius Hybrida in 62. He is called strategos (Greek στρατηγός) in an inscription from Delphi (SEG I. 165 Delphi). There is no evidence of his official position under Lentulus.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ P.G.P. Meyboom, The Nile Mosaic of Palestrina: Early Evidence of Egyptian Religion in Italy, Brill (1995), p. 161.

- ^ Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, pp. 83, 86, 87, 408, 415, 418.

- ^ Chase, pp. 129–132.

- ^ a b Wiseman, New Men in the Roman Senate, p. 251.

- ^ McCartney, "Casting Puns on Ancient Monuments", p. 62.

- ^ Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, p. 418.

- ^ Censorinus, De Die Natali xxiv. 3.

- ^ Plautus, Epidicus, 25–27.

- ^ Varro, De Lingua Latina, vi. 5.

- ^ Gellius, iii. 2.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 472.

- ^ Livy, xxxiv. 45.

- ^ Cicero, De Officiis, iii. 61, De Natura Deorum, iii. 74.

- ^ lex Julia Municipalis.

- ^ Plautus, Pseudolus, 303 ff, Rudens, 1380–1382 ff.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 472.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 472.

- ^ Livy, xlii. 26

- ^ Broughton, vol. 1, p. 414.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 494 (Senatus consultum de Agro Pergameno, with Plattorius amended to Plaetorius).

- ^ Valerius Maximus, ix. 2. § 1.

- ^ Florus, ii. 9. § 26 (without praenomen).

- ^ Orosius, v. 21. § 8 (as P. Laetorius).

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 494; MRR3, p. 157.

- ^ Cicero, Pro Cluentio, 165.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 102; MRR3, p. 157.

- ^ Cicero, Epistulae Ad familiares, i. 8. § 1.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, pp. 128, 143, 150 (note 3), 161, 162; MRR3, p. 157.

- ^ Ronald Syme, reviewing Broughton's MRR in Classical Philology, vol. 50, No. 2 (1955), pp. 129–130, 132.

- ^ SEG, I. 165 Delphi.

- ^ Hirtius, De Bello Alexandrino, 34.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 274.

- ^ Hirtius, De Bello Africo, 96.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 494.

- ^ Broughton, MRR2, p. 360.

- ^ Aelius Spartianus, "The Life of Hadrian", 4, 23.

Bibliography

edit- Titus Maccius Plautus, Epidicus, Pseudolus, Rudens.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Natura Deorum, De Officiis, Pro Cluentio, Pro Fonteio.

- Aulus Hirtius (attributed), De Bello Alexandrino (On the Alexandrine War), De Bello Africo (On the African War).

- Marcus Terentius Varro, De Lingua Latina (On the Latin Language).

- Titus Livius (Livy), History of Rome.

- Valerius Maximus, Factorum ac Dictorum Memorabilium (Memorable Facts and Sayings).

- Lucius Annaeus Florus, Epitome de T. Livio Bellorum Omnium Annorum DCC (Epitome of Livy: All the Wars of Seven Hundred Years).

- Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae (Attic Nights).

- Censorinus, De Die Natali.

- Aelius Lampridius, Aelius Spartianus, Flavius Vopiscus, Julius Capitolinus, Trebellius Pollio, and Vulcatius Gallicanus, Historia Augusta (Augustan History).

- Paulus Orosius, Historiarum Adversum Paganos (History Against the Pagans).

- Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, William Smith, ed., Little, Brown and Company, Boston (1849).

- August Pauly, Georg Wissowa, et alii, Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft (Scientific Encyclopedia of the Knowledge of Classical Antiquities, abbreviated RE or PW), J. B. Metzler, Stuttgart (1894–1980).

- George Davis Chase, "The Origin of Roman Praenomina", in Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, vol. VIII (1897).

- Eugene S. McCartney, "Casting Puns on Ancient Monuments", in American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 23 (1919).

- J. J. E. Hondius, A. G. Woodhead, et alii, Supplemtentum Epigraphicum Graecum (abbreviated SEG), J. C. Glieben, Amsterdam, E. J. Brill, Leiden (1923–present).

- T. Robert S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, American Philological Association (1952–1986).

- T.P. Wiseman, New Men in the Roman Senate, 139 B.C.–A.D. 14, Oxford University Press (1971).

- Michael Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, Cambridge University Press (1974).