A request that this article title be changed to Athletics (baseball) is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

The Athletics (often referred to as the A's) are an American professional baseball team based in West Sacramento, California.[4] The Athletics compete in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a member club of the American League (AL) West Division. The team will play its home games at Sutter Health Park in West Sacramento for the 2025–2027 seasons before its permanent move to Las Vegas.[5] While in West Sacramento, the team is being referred to as simply the "Athletics" and "A's", with no city name attached.[6] The franchise's nine World Series championships, fifteen pennants, and seventeen division titles are the second-most in the AL after the New York Yankees.

| Athletics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| |||||

| Major league affiliations | |||||

| |||||

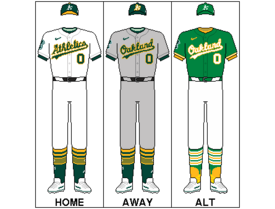

| Current uniform | |||||

| |||||

| Retired numbers | |||||

| Colors | |||||

| Name | |||||

| |||||

| Other nicknames | |||||

| |||||

| Ballpark | |||||

| |||||

| Major league titles | |||||

| World Series titles (9) | |||||

| AL Pennants (15) | |||||

| West Division titles (17) | |||||

| Wild card berths (4) | |||||

| Front office | |||||

| Principal owner(s) | John Fisher | ||||

| President | Dave Kaval | ||||

| General manager | David Forst | ||||

| Manager | Mark Kotsay | ||||

| Website | mlb.com/athletics | ||||

One of the AL's eight charter franchises, the team was founded in Philadelphia in 1901 as the Philadelphia Athletics. They won three World Series championships in 1910, 1911, and 1913, and back-to-back titles in 1929 and 1930. The team's owner and manager for its first 50 years was Connie Mack, and Hall of Fame players included Chief Bender, Frank "Home Run" Baker, Jimmie Foxx, and Lefty Grove. The team left Philadelphia for Kansas City in 1955 and became the Kansas City Athletics, before moving to Oakland, California, in 1968 and becoming the Oakland Athletics. The Athletics played their home games at the Oakland Coliseum from 1968 until 2024. Nicknamed the "Swingin' A's", under owner Charlie O. Finley they won three consecutive World Series in 1972, 1973, and 1974, led by players including Vida Blue, Catfish Hunter, Reggie Jackson, and Rollie Fingers. After being sold by Finley to Walter A. Haas Jr., the team won three consecutive pennants and the 1989 World Series behind the "Bash Brothers", Jose Canseco and Mark McGwire, as well as Hall of Famers Dennis Eckersley, Rickey Henderson and manager Tony La Russa. In 2002, the Athletics set the record for most consecutive wins in a season with twenty, an event that would go on to be the pioneering step in the application of sabermetrics in baseball.

From 1901 through the end of 2024, the franchise's overall win–loss record is 9,329–9,859–87 (.486). In Oakland, from 1968 to 2024, the Athletics had an overall win–loss record of 4,614–4,387 (.513).[7]

History

editThe history of the Athletics Major League Baseball franchise spans from 1901 to the present day, having begun in Philadelphia before moving to Kansas City in 1955 and then to its home in Oakland, California, in 1968. The A's made their Bay Area debut on Wednesday, April 17, 1968, with a 4–1 loss to the Baltimore Orioles at the Coliseum, in front of an opening-night crowd of 50,164.[8] With four locations, the A's have had the most home cities of any MLB team.[9]

Team name and "A" logo

editThe Athletics' name originated in the term "Athletic Club" for local gentlemen's clubs—dates to 1860 when an amateur baseball team, the Athletic (Club) of Philadelphia, was formed. The team later turned professional in 1875, becoming a charter member of the National League in 1876, but were expelled from the N.L. after one season. A later version of the Athletics played in the American Association from 1882 to 1891.[10]

The familiar blackletter "A" is one of the oldest sports logos still in use. An image in Harper's Weekly with the rival Brooklyn Atlantics shows that the "A" appeared on the original Athletics' uniform as early as 1866.[11]

Elephant mascot

editAfter New York Giants manager John McGraw told reporters that Philadelphia manufacturer Benjamin Shibe, who owned the controlling interest in the new team, had a "white elephant on his hands", team manager Connie Mack defiantly adopted the white elephant as the team mascot, and presented McGraw with a stuffed toy elephant at the start of the 1905 World Series.[12] McGraw and Mack had known each other for years, and McGraw accepted it graciously. By 1909, the A's were wearing an elephant logo on their sweaters, and in 1918 it turned up on the regular uniform jersey for the first time.[13]

In 1963, when the A's were located in Kansas City, then-owner Charlie Finley changed the team mascot from an elephant to a mule, the state animal of Missouri. This is rumored to have been done by Finley in order to appeal to fans from the region who were predominantly Democrats at the time. (The traditional Republican Party symbol is an elephant, while the Democratic Party's symbol is a donkey.)[14] Since 1988, the Athletics' 21st season in Oakland, an illustration of an elephant has adorned the left sleeve of the A's home and road uniforms. Beginning in the mid-1980s, the on-field costumed incarnation of the A's elephant mascot went by the name Harry Elephante, a play on the name of singer Harry Belafonte.[15] In 1997, he became Stomper, debuting Opening Night on April 2.[16][17]

Uniforms

editOver the seasons, the Athletics' uniforms have paid homage to their amateur forebears. Until 1954, when the uniforms had "Athletics" spelled out in script across the front, the team's name never appeared on either home or road uniforms. Furthermore, neither "Philadelphia" nor the letter "P" appeared on the uniform or cap. The Philadelphia uniform had only a script "A" on the left front, and likewise the cap usually had the same "A" on it. In the early days of the American League, the standings listed the club as "Athletic" rather than "Philadelphia", in keeping with the old tradition. Eventually, the city name came to be used for the team, as with the other major league clubs.

After buying the team in 1960, owner Charles O. Finley introduced road uniforms with "Kansas City" printed on them, with an interlocking "KC" on the cap. Upon moving to Oakland, the "A" cap emblem was restored, and in 1970 an "apostrophe-s" was added to the cap and uniform emblem to reflect that Finley was officially changing the team's name to the "A's".

While in Kansas City, Finley changed the team's colors from their traditional red, white and blue to what he termed "Kelly Green, Wedding Gown White and Fort Knox Gold". It was here that he began experimenting with dramatic uniforms to match these bright colors, such as gold sleeveless tops with green undershirts and gold pants. The uniform innovations increased after the team's move to Oakland, which came with the introduction of polyester pullover uniforms.

During their dynasty years in the 1970s, the A's had dozens of uniform combinations with jerseys and pants in all three team colors, and never wore the traditional gray on the road, instead wearing green or gold, which helped to contribute to their nickname of "The Swingin' A's". After the team's sale to the Haas family, the team changed its primary color to a more subdued forest green in 1982 and began a move back to more traditional uniforms.

The 2023 team wore home uniforms with "Athletics" spelled out in script writing and road uniforms with "Oakland" spelled out in script writing, with the cap logo consisting of the traditional "A" with "apostrophe-s". The home cap, which was also the team's road cap until 1992, is forest green with a gold bill and white lettering. This design was also the basis of their batting helmet, which is used both at home and on the road. The road cap, which initially debuted in 1993, is all-forest green. The first version had the white "A's" wordmark before it was changed to gold the following season. An all-forest green batting helmet was paired with this cap until 2008. In 2014, the "A's" wordmark returned to white but added gold trim.

From 1994 until 2013, the A's wore green alternate jerseys with the word "Athletics" in gold, for both road and home games.

During the 2000s, the Athletics introduced black as one of their colors. They began wearing a black alternate jersey with "Athletics" written in green. After a brief discontinuance, the A's brought back the black jersey, this time with "Athletics" written in white with gold highlights. The cap paired with this jersey is all-black, initially with the green and white-trimmed "A's" wordmark, before switching to a white and gold-trimmed "A's" wordmark. Commercially popular but rarely chosen as the alternate by players, the black uniform was retired in 2011 in favor of a gold alternate jersey.

The gold alternate has "A's" in green trimmed in white on the left chest. With the exception of several road games during the 2011 season, the Athletics' gold uniforms were used as the designated home alternates. A green version of their gold alternates was introduced for the 2014 season, serving as a replacement to the previous green alternates. The new green alternates featured the piping, "A's" and lettering in white with gold trim.

In 2018, as part of the franchise's 50th anniversary since the move to Oakland, the A's wore a kelly green alternate uniform with "Oakland" in white with gold trim, and was paired with an all-kelly green cap.[18] This set was later worn with an alternate kelly green helmet with gold visor. This uniform eventually supplanted the gold alternates by 2019, and in 2022, after the forest green alternate was retired, it became the team's only active alternate uniform.

The nickname "A's" has long been used interchangeably with "Athletics", dating to the team's early days when headline writers used it to shorten the name. From 1972 through 1980, the team name was officially "Oakland A's", although the Commissioner's Trophy, given out annually to the winner of baseball's World Series, still listed the team's name as the "Oakland Athletics" on the gold-plated pennant representing the Oakland franchise. According to Bill Libby's Book, Charlie O and the Angry A's, owner Charlie O. Finley banned the word "Athletics" from the club's name because he felt that name was too closely associated with former Philadelphia Athletics owner Connie Mack, and he wanted the name "Oakland A's" to become just as closely associated with him. The name also vaguely suggested the name of the old minor league Oakland Oaks, which were alternatively called the "Acorns". New owner Walter Haas restored the official name to "Athletics" in 1981, but retained the nickname "A's" for marketing. At first, the word "Athletics" was restored only to the club's logo, underneath the much larger stylized-"A" that had come to represent the team since the early days. By 1987, however, the word returned, in script lettering, to the front of the team's jerseys.

From 2025 to 2027, while the team temporarily plays its home games in West Sacramento, all of its uniforms would feature the "Athletics" wordmark.

Prior to the mid-2010s, the A's had a long-standing tradition of wearing white cleats team-wide (in line with the standard MLB practice that required all uniformed team members to wear a base cleat color), which dated to the Finley ownership. Since the mid-2010s, however, MLB has gradually relaxed its shoe color rules, and several A's players began wearing cleats in non-white colors, such as Jed Lowrie's green cleats.

Ballpark history and future

editThe Oakland Coliseum—originally the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum, and later named as Network Associates, McAfee, Overstock.com/O.co and RingCentral Coliseum—was built as a multi-purpose facility. Louisiana Superdome officials pursued negotiations with Athletics officials during the 1978–79 baseball offseason about moving the Athletics to their facility in New Orleans. The Athletics were unable to break their lease at the Coliseum, and remained in Oakland.[19]

After the Oakland Raiders football team moved to Los Angeles in 1982, many improvements were made to what was suddenly a baseball-only facility. The 1994 movie Angels in the Outfield was filmed in part at the Coliseum, filling in for Anaheim Stadium.

In 1995, the Raiders moved back to Oakland. The Coliseum was expanded to 63,026 seats. The bucolic view of the Oakland foothills that baseball spectators enjoyed was replaced with a jarring view of an outfield grandstand contemptuously referred to as "Mount Davis" after Raiders' owner Al Davis. Because construction was not finished by the start of the 1996 season, the Athletics were forced to play their first six-game homestand at 9,300-seat Cashman Field in Las Vegas, Nevada.[20]

Although official capacity was listed as 43,662 for baseball, seats were sometimes sold in Mount Davis, pushing actual capacity to nearly 60,000. The ready availability of tickets on game day made season tickets a tough sell, while crowds as high as 30,000 often seemed sparse in such a venue. On December 21, 2005, the Athletics announced that seats in the Coliseum's third deck would not be sold for the 2006 season, but would instead be covered with a tarp, and that tickets would no longer be sold in Mount Davis under any circumstances. That effectively reduced capacity to 34,077, making the Coliseum the lowest-capacity stadium in Major League Baseball. Beginning in 2008, sections 316–318 immediately behind home plate were the only third-deck sections open for A's games, which brought the total capacity to 35,067 until 2017, when new team president Dave Kaval took the tarps off of the upper deck, increasing capacity to 47,170. The Athletics were the last MLB team to share a stadium full-time with an NFL team, a situation that ended when the Raiders moved to Las Vegas in 2020.

The Athletics' spring training facility is Hohokam Stadium, in Mesa, Arizona. From 1982 to 2014, their spring training facility was Phoenix Municipal Stadium, in Phoenix, Arizona; they also spent time playing in Scottsdale, Arizona.[21][22]

Improvements to the Coliseum

editNew areas

editIn 2017, the team created an outdoor plaza in the space between the Coliseum and Oracle Arena. The grassy area is open to all ticketed fans, and it features food trucks, seating and games like corn hole for every Athletics home game.[23][24] The following year, the team introduced The Treehouse, a 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) area open to all fans with two full-service bars, standing-room and lounge seating, numerous televisions with pre-game and postgame entertainment. The A's Stomping Ground transformed part of the Eastside Club and the area near the right-field flag poles into a fun and interactive space for kids and families. The inside section features a stage and video wall for interactive events, a digital experience that lets youngsters race their favorite Athletics players, replica team dugouts, a simulated hitting and pitching machine, foosball, and a photo booth. The outside area includes play areas, a grassy seating area, drink rails for parents, and picnic tables, a miniature baseball field and spiderweb play area.[25]

Premium spaces

editThe team added three new premium spaces, including The Terrace, Lounge Seats, and the Coppola Theater Boxes, to the Coliseum for the 2019 season. The new premium seating options offer fans a high-end game-day experience with luxury amenities. The team also added two new group spaces – the Budweiser Hero Deck and Golden Road Landing – to the Coliseum.[26]

Other additions

editIn addition, the tarps on the upper deck were removed; a modern version of the beloved mechanical Harvey the Rabbit to deliver the first pitch ball was re-introduced, while the playing surface at the Coliseum was renamed "Rickey Henderson Field". The team held the first free game in MLB history for 46,028 fans on April 17, 2018, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Athletics first game in Oakland.[27] The team tried a new concept in season ticketing in the A's Access plan that involved "general admission access to every home game with a set number of reserved-seat upgrades allotted", which was meant to replace previous attempts at subscription-based services that they tried with Ballpark Pass and Treehouse Pass.[28] On July 21, 2018, the Athletics set a Coliseum record for the largest attendance with a crowd of 56,310 when the team hosted to the San Francisco Giants.[28][29]

Prior stadium proposals

editOakland

editSince the early 2000s, the A's have been in talks with Oakland and other Northern California cities about building a new baseball-only stadium. The team had said it wanted to remain in Oakland. A 2017 plan would have placed a new 35,000 seat A's stadium near Laney College and the Eastlake neighborhood on the site of the Peralta Community College District's administration buildings. The plan was announced by team president Dave Kaval in September 2017.[30] However, three months later, negotiations abruptly ended.[31] On November 28, 2018, the Athletics announced that the team had chosen to build its new 34,000-seat ballpark at the Howard Terminal site at the Port of Oakland. The team also announced its intent to purchase the Coliseum site and renovate it into a tech and housing hub, preserving Oakland Arena and reducing the Coliseum to a low-rise sports park as San Francisco did with Kezar Stadium.[32] In April 2023, the City of Oakland ended discussions with the Athletics organization after the announcement of a new ballpark in Las Vegas, amid widespread claims that the team was not negotiating in good faith and was using the proposed site in Oakland to leverage a better deal in Las Vegas instead of any real intention to stay within the city.[33]

Fremont

editOn November 7, 2006, the news media announced the Athletics would be leaving Oakland as early as 2010 for a new stadium in Fremont, confirmed the next day by the Fremont City Council. The plan was strongly supported by Fremont Mayor Bob Wasserman.[34] The team would have played in Cisco Field, a 32,000-seat, baseball-only facility.[35] The proposed ballpark would have been part of a larger "ballpark village" which would have included retail and residential development. On February 24, 2009, however, Lew Wolff released an open letter announcing the end of his efforts to relocate the A's to Fremont, citing "real and threatened" delays to the project.[36] The project faced opposition from some in the community who thought the relocation of the A's to Fremont would increase traffic problems in the city and decrease property values near the ballpark site.

San Jose

editIn 2009, the City of San Jose attempted to open negotiations with the team regarding a move to the city. Although land south of Diridon Station would be acquired by the city as a stadium site, the San Francisco Giants' claim on Santa Clara County as part of their home territory would have to be settled before any agreement could be made.[37]

By 2010, San Jose was "aggressively wooing" A's owner Lew Wolff, the city as the team's "best option", but Major League Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig said he would await a report on whether the team could move to the area, because of the Giants conflict.[38] In September 2010, 75 Silicon Valley CEOs drafted and signed a letter to Bud Selig urging a timely approval of the move to San Jose.[39] In May 2011, San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed sent a letter to Bud Selig asking the commissioner for a timetable of when he might decide whether the A's can pursue this new ballpark, but Selig did not respond.[40]

Selig addressed the San Jose issue via an online town hall forum held in July 2011, saying, "Well, the latest is, I have a small committee who has really assessed that whole situation, Oakland, San Francisco, and it is complex. You talk about complex situations; they have done a terrific job. I know there are some people who think it's taken too long and I understand that. I'm willing to accept that. But you make decisions like this; I've always said, you'd better be careful. Better to get it done right than to get it done fast. But we'll make a decision that's based on logic and reason at the proper time."[41]

On June 18, 2013, the City of San Jose filed suit against Selig, seeking the court's ruling that Major League Baseball may not prevent the Oakland A's from moving to San Jose.[42] Wolff criticized the lawsuit, stating he did not believe business disputes should be settled through legal action.[43]

Most of the city's claims were dismissed in October 2013, but a U.S. District Judge ruled that San Jose could move forward with its claim that MLB illegally interfered with a land agreement between the city and the A's. On January 15, 2015, a three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled unanimously that the claims were barred by baseball's antitrust exemption, established by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1922 and upheld in 1953 and 1972. San Jose Mayor Sam Liccardo commented that the city would seek a ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court.[44] On October 5, 2015, the United States Supreme Court rejected San Jose's case.[45]

Relocation to Las Vegas

editFollowing the California Golden Seals' relocation to Cleveland in 1976, the Golden State Warriors' move across the bay to San Francisco in 2019, and the Oakland Raiders' move to Las Vegas in 2020, the Athletics were left as the sole remaining professional sports team in Oakland. However, on April 20, 2023, the Athletics announced they had entered a land purchase agreement with Red Rock Resort located near Las Vegas to build a new ballpark on the Las Vegas Strip, finalizing their plans to relocate to the Las Vegas area.[46][47][48][49] On May 9, 2023, the Athletics switched their planned location in the Las Vegas area to the site of the Tropicana Las Vegas hotel and casino, which was subsequently demolished in October to construct a 33,000-seat partially retractable ballpark and a 1,500-room hotel and casino.[50][51][52] By June 15, 2023, Nevada governor Joe Lombardo signed an MLB stadium funding bill known as SB1 into law after the bill was approved by the Nevada Legislature, and the Athletics officially announced they would begin the relocation process.[53]

On November 16, 2023, the Athletics' move to Las Vegas was unanimously approved by MLB team owners.[54] According to the team, the new Las Vegas ballpark will not be completed until 2028. The lease to the Oakland Coliseum expired after the 2024 season. Before the scheduled move to Las Vegas in 2028, the team will play in West Sacramento, California at Sutter Health Park (home of the San Francisco Giants' Triple-A affiliate, the Sacramento River Cats) for the 2025–2027 seasons (with an option for the 2028 season if necessary).[55] While in West Sacramento the team will be referred to as simply the "A's" and "Athletics," with no city name attached.[6] The relocation will mark the first move by an MLB team since the Montreal Expos moved to Washington, D.C., becoming the Washington Nationals in 2005.

Rivalries

editSan Francisco Giants

editThe Bay Bridge Series is the name of a series of games played between (and the rivalry of) the A's and San Francisco Giants of the National League. The series takes its name from the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge which links the cities of Oakland and San Francisco. Although competitive, the regional rivalry between the A's and Giants is considered a friendly one with mostly mutual companionship between the fans, as opposed to White Sox–Cubs, or Yankees–Mets games where animosity runs high. Hats displaying both teams on the cap are sold from vendors at the games, and once in a while the teams both dress in original team uniforms from the early era of baseball. The series is also occasionally referred to as the "BART Series" for the Bay Area Rapid Transit system that links Oakland to San Francisco. However, the name "BART Series" has never been popular beyond a small selection of history books and national broadcasters and has fallen out of favor. Bay Area locals almost exclusively refer to the rivalry as the "Battle of the Bay".[56]

Originally, the term described a series of exhibition games played between the two clubs after the conclusion of spring training, immediately prior to the start of the regular season. It was first used to refer to the 1989 World Series in which the Athletics won their most recent championship and the first time the teams had met since they moved to the San Francisco Bay Area (and the first time they had met since the A's also defeated the Giants in the 1913 World Series). Today, it also refers to games played between the teams during the regular season since the commencement of interleague play in 1997. Through the 2021 regular season, the Athletics have won 71 games, and the Giants have won 65 contests.[57]

Through the 2021 season, the A's also have edges on the Giants in terms of overall postseason appearances (21–13), division titles (17–10) and World Series titles (4–3) since both teams moved to the Bay Area, even though the Giants franchise moved there a decade earlier than the A's did.

On March 24, 2018, the Oakland A's announced that for the Sunday, March 25, 2018, exhibition game against the San Francisco Giants, A's fans would be charged $30 for parking and Giants fans would be charged $50. However, the A's stated that Giants fans could receive $20 off if they shout "Go A's" at the parking gates.[58]

In 2018, the Athletics and Giants started battling for a "Bay Bridge" Trophy[59] made from steel taken from the old east span of the Bay Bridge, which was taken down after the new span was opened in 2013.[60][61] The A's won the inaugural season with the trophy, allowing them to place their logo atop its Bay Bridge stand.[62]

Los Angeles Angels

editThe A's have held a rivalry with the Los Angeles Angels since their relocation to California in 1968, and the charter membership of both teams in the AL West in 1969. The A's and Angels have often competed for the division title.[63] The peak of the rivalry was during the early part of the millennium as both teams were perennial contenders. During the 2002 season, the A's famous "Moneyball" tactics led them to a league record 20-game winning streak, knocking the Angels out of the first seed in the division. The A's finished 4 games ahead while the Angels secured the Wild Card berth.[64] Despite the 103-win season for Oakland, they lost to the underdog Minnesota Twins in the ALDS. The Angels beat the heavily favored New York Yankees, then beat the Twins, and then won the 2002 World Series. During the 2004 season, the teams were tied for wins headed into the final week of September with the last three games being played in Oakland against the Angels.[65] Both teams were battling to secure the division championship. Oakland lost two of the three games to the Angels, and they were eliminated from the playoff hunt. The Angels were swept in the playoffs by the eventual champion Boston Red Sox.[66] The Athletics lead the series 527–479, and the two teams have yet to meet in the postseason.

Philadelphia Phillies (historic)

editThe City Series was the name of baseball games played between the Philadelphia Athletics and the Philadelphia Phillies of the National League, that ran from 1903 through 1955. After the A's move to Kansas City in 1955, the City Series rivalry came to an end. Since the introduction of interleague play in 1997, the teams have since faced each other during the regular season (with the first games taking place in 2003) but the rivalry had effectively died in the intervening years since the A's left Philadelphia. In 2014, when the A's faced the Phillies in inter-league play at the Oakland Coliseum, the Athletics did not bother to mark the historical connection, going so far as to have a Connie Mack promotion the day before the series while the Texas Rangers were in Oakland.[67]

The first City Series was held in 1883 between the Phillies and the American Association Philadelphia Athletics.[68] When the Athletics first joined the American League, the two teams played each other in a spring and fall series. No City Series was held in 1901 and 1902 due to legal warring between the National League and American League.

Achievements

editAwards

edit- The Athletics give out an award named the Catfish Hunter Award since 2004 for the most inspirational Athletic.

Hall of Famers

edit| Oakland Athletics Hall of Famers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ford C. Frick Award recipients

edit| Oakland Athletics Ford C. Frick Award recipients | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Affiliation according to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum | |||||||||

|

Retired numbers

editThe Athletics have retired six numbers; additionally, Walter A. Haas, Jr., owner of the team from 1980 until his death in 1995, was honored by the retirement of the letter "A". Of the six players with retired numbers, five were retired for their play with the Athletics and one, 42, was universally retired by Major League Baseball when they honored the 50th anniversary of Jackie Robinson's breaking the color barrier. No A's player from the Philadelphia era has his number retired by the organization. Though Jackson and Hunter played small portions of their careers in Kansas City, no player that played the majority of his years in the Kansas City era has his number retired either. The A's have retired only the numbers of Hall-of-Famers who played large portions of their careers in Oakland. The Athletics have all of the numbers of the Hall-of-Fame players from the Philadelphia Athletics displayed at their stadium, as well as all of the years that the Philadelphia Athletics won World Championships (1910, 1911, 1913, 1929, and 1930). Dave Stewart was about to have his #34 jersey retired by the Athletics in 2020, but the ceremony was postponed until further notice, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Questions were raised if there would be a formal ceremony after no news about a reschedule happened in 2021 before it was announced in April 2022 that Stewart would have his jersey retired on September 11, 2022.[69][70] Stewart broke the A's tradition in that his number was a re-retirement, as well as his not being in the Hall of Fame.

|

Athletics Hall of Fame

editOn August 14, 2018, the team publicly announced the creation of a team Hall of Fame, complete with the first seven names to be inducted.[71] On September 5, the Athletics held a ceremony to induct seven members into the inaugural class. Each member was honored with an unveiling of a painting in their likeness and a bright green jacket. Hunter, who died in 1999, was represented by his widow, while Finley, who died in 1996, was represented by his son. If the team ever gets a new stadium, a physical site will be designated for the Hall of Fame, as the Coliseum does not have enough space for a full-fledged exhibit.[72] In August 2021, it was announced that players Sal Bando, Eric Chavez, Joe Rudi, director of player development Keith Lieppman, and clubhouse manager Steve "Vuc" Vucinich would be part of the class of 2022; in November 2021, Ray Fosse, who had died the previous month, was posthumously inducted into the Hall of Fame.[73][74] The 2023 class was inducted in August.[75] On August 17, 2024, the Hall of Fame will see the induction of Jose Canseco, Terry Steinbach, Miguel Tejada, Dick Williams, Bill King, and Eddie Joost.[76]

| Bold | Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame |

|---|---|

†

|

Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame as an Athletic |

| Bold | Recipient of the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award |

| Athletics Hall of Fame | ||||

| Year | No. | Player | Position | Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 43 | Dennis Eckersley† | P | 1987–1995 |

| 32, 38, 34 | Rollie Fingers† | P | 1968–1976 | |

| 39, 35, 22, 24 | Rickey Henderson† | LF | 1979–1984 1989–1993 1994–1995 1998 | |

| 27 | Catfish Hunter | P | 1965–1974 | |

| 9, 44 | Reggie Jackson | RF | 1967–1975 1987 | |

| 34, 35 | Dave Stewart | P | 1986–1992 1995 | |

| — | Charlie Finley | Owner General Manager |

1960–1981 | |

| 2019 | 10, 11, 22, 29, 42 | Tony La Russa | IF Manager |

1963 1968–1971 1986–1995 |

| 14, 17, 21, 28, 35 | Vida Blue | P | 1969–1977 | |

| 19 | Bert "Campy" Campaneris | SS | 1964–1976 | |

| 25 | Mark McGwire | 1B | 1986–1997 | |

| — | Walter A. Haas, Jr. | Owner | 1981–1995 | |

| — | Walter A. Haas, Jr. | Owner | 1981–1995 | |

| 2021 | — | Connie Mack† | Manager Owner |

1901–1950 1901–1954 |

| — | Eddie Collins | 2B | 1906–1914 1927–1930 | |

| — | Frank "Home Run" Baker† | 3B | 1908–1914 | |

| — | Charles "Chief" Bender† | P | 1903–1914 | |

| 2 | Mickey Cochrane | C | 1925–1933 | |

| 2, 3 | Jimmie Foxx | 1B | 1925–1935 | |

| 10 | Lefty Grove | P | 1925–1933 | |

| — | Eddie Plank† | P | 1901–1914 | |

| 6, 7, 28, 32 | Al Simmons† | LF Coach |

1924–1932 1940–1941, 1944 1940–1945 | |

| — | Rube Waddell† | P | 1902–1907 | |

| 2022 | 30, 3 | Eric Chavez | 3B | 1998–2010 |

| 6 | Sal Bando | 3B | 1966–1976 | |

| 15, 45, 8, 36, 26 | Joe Rudi | LF / 1B | 1967–1976 1982 | |

| 10 | Ray Fosse | C Broadcaster |

1973–1975 1986–2021 | |

| — | Keith Lieppman | Director of Player Development | 1971–present | |

| — | Steve Vucinich | Clubhouse manager | 1966–present | |

| 2023 | 16 | Jason Giambi | LF / 1B | 1995–2001 2009 |

| 26, 7, 4 | Bob Johnson | LF | 1933–1942 | |

| 5, 4 | Carney Lansford | 3B | 1983–1992 | |

| 24, 38, 18 | Gene Tenace | C / 1B | 1969–1976 | |

| — | Roy Steele | Public address announcer | 1968–2005 2007–2008 | |

| 2024 | 33 | Jose Canseco | RF / DH | 1985–1992 1997 |

| 1 | Eddie Joost | SS Manager |

1947–1954 1954 | |

| 36 | Terry Steinbach | C | 1986–1996 | |

| 4 | Miguel Tejada | SS | 1997–2003 | |

| 23 | Dick Williams† | LF / 3B Manager |

1959–1960 1971–1973 | |

| — | Bill King | Broadcaster | 1981–2005 | |

Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

edit17 members of the Athletics organization have been honored with induction into the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame.

| Athletics in the Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame | ||||

| No. | Player | Position | Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | Dusty Baker | OF | 1985–1986 | |

| 14, 17, 21, 28, 35 | Vida Blue | P | 1969–1977 | |

| 19 | Bert "Campy" Campaneris | SS | 1964–1976 | |

| 12 | Orlando Cepeda | 1B | 1972 | Elected mainly on his performance with San Francisco Giants |

| 4, 6, 10, 14 | Sam Chapman | CF | 1938–1941 1945–1951 |

Born and raised in Tiburon, California |

| 43 | Dennis Eckersley | P | 1987–1995 | Grew up in Fremont, California |

| 32, 34, 38 | Rollie Fingers | P | 1968–1976 | |

| — | Walter A. Haas, Jr. | Owner | 1981–1995 | Grew up in San Francisco, California, attended UC Berkeley |

| 24 | Rickey Henderson | LF | 1979–1984 1989–1993 1994–1995 1998 |

Raised in Oakland, California |

| 27 | Catfish Hunter | P | 1965–1974 | |

| 9, 31, 44 | Reggie Jackson | RF | 1968–1975 1987 |

|

| 1 | Eddie Joost | SS Manager |

1947–1954 1954 |

Born and raised in San Francisco, California |

| 10, 11, 22, 29, 42 | Tony La Russa | IF Manager |

1963 1968–1971 1986–1995 |

|

| 1, 4 | Billy Martin | 2B Manager |

1957 1980–1982 |

Elected mainly on his performance with New York Yankees, Born in Berkeley, California |

| 44 | Willie McCovey | 1B | 1976 | Elected mainly on his performance with San Francisco Giants |

| 8 | Joe Morgan | 2B | 1984 | Elected mainly on his performance with Cincinnati Reds, raised in Oakland, California |

| 19 | Dave Righetti | P | 1994 | Born and raised in San Jose, California |

| 34 | Dave Stewart | P | 1986–1992 1995 |

Born and raised in Oakland, California |

Philadelphia Baseball Wall of Fame

editThe Athletics have all of the numbers of the Hall-of-Fame players from the Philadelphia Athletics displayed at their stadium, as well as all of the years that the Philadelphia Athletics won World Championships (1910, 1911, 1913, 1929, and 1930).

Also, from 1978 to 2003 (except 1983), the Philadelphia Phillies inducted one former Athletic (and one former Phillie) each year into the Philadelphia Baseball Wall of Fame at the then-existing Veterans Stadium. 25 Athletics have been honored. In March 2004, after Veterans Stadium was replaced by the new Citizens Bank Park, the Athletics' plaques were relocated to the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society in Hatboro, Pennsylvania,[77][78][79] and a single plaque listing all of the A's inductees was attached to a statue of Connie Mack that is located across the street from Citizens Bank Park.[80][81]

| Year | Year inducted |

|---|---|

| Bold | Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame |

†

|

Member of the Baseball Hall of Fame as a member of the A's |

| Bold | Recipient of the Hall of Fame's Ford C. Frick Award |

| Philadelphia Baseball Wall of Fame | ||||

| No. | Player | Position | Tenure | Inducted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | Frank "Home Run" Baker† | 3B | 1908–1914 | 1993 |

| — | Charles "Chief" Bender† | P | 1903–1914 | 1991 |

| 4, 6, 10, 14 | Sam Chapman | CF | 1938–1951 | 1999 |

| 2 | Mickey Cochrane | C | 1925–1933 | 1982 |

| — | Eddie Collins | 2B | 1906–1914 1927–1930 |

1987 |

| — | Jack Coombs | P | 1906–1914 | 1992 |

| 5 | Jimmy Dykes | 3B/2B Coach Manager |

1918–1932 1940–1950 1951–1953 |

1984 |

| 11 | George Earnshaw | P | 1928–1933 | 2000 |

| 5, 8 | Ferris Fain | 1B | 1947–1952 | 1997 |

| 2, 3, 4 | Jimmie Foxx | 1B | 1925–1935 | 1979 |

| 10 | Lefty Grove | P | 1925–1933 | 1980 |

| 4, 7, 26 | "Indian Bob" Johnson | LF | 1933–1942 | 1989 |

| 1 | Eddie Joost | SS Manager |

1947–1954 1954 |

1995 |

| — | Connie Mack† | Manager Owner |

1901–1950 1901–1954 |

1978 |

| 9, 27 | Bing Miller | RF | 1922–1926 1928–1934 |

1998 |

| 1, 2, 9, 19 | Wally Moses | RF | 1935–1941 1949–1951 |

1988 |

| — | Rube Oldring | CF | 1906–1916 1918 |

2003 |

| — | Eddie Plank† | P | 1901–1914 | 1985 |

| 14 | Eddie Rommel | P | 1920–1932 | 1996 |

| 21, 30 | Bobby Shantz | P | 1949–1954 | 1994 |

| 6, 7, 28, 32 | Al Simmons† | LF Coach |

1924–1932 1940–1941, 1944 1940–1945 |

1981 |

| 10, 15, 21, 35, 38 | Elmer Valo | RF | 1940–1954 | 1990 |

| — | Rube Waddell† | P | 1902–1907 | 1986 |

| 12 | Rube Walberg | P | 1923–1933 | 2002 |

| 6, 19, 30 | Gus Zernial | LF | 1951–1954 | 2001 |

Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame

edit| Athletics in the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name | Position | Tenure | Inducted | Notes |

| — | Connie Mack | Manager Owner |

1901–1950 1901–1954 |

2004 | |

| 2, 3, 4 | Jimmie Foxx | 1B | 1925–1935 | 2004 | |

| 10 | Lefty Grove | P | 1925–1933 | 2005 | |

| 6, 7, 28, 32 | Al Simmons | LF Coach |

1924–1932 1940–1941, 1944 1940–1945 |

2006 | |

| 2 | Mickey Cochrane | C | 1925–1933 | 2007 | |

| — | Eddie Collins | 2B | 1906–1914 1927–1930 |

2009 | |

| 21, 30 | Bobby Shantz | P | 1949–1954 | 2010 | |

| 5 | Jimmy Dykes | 3B/2B Coach Manager |

1918–1932 1940–1950 1951–1953 |

2011 | Born in Philadelphia |

| — | Eddie Plank | P | 1901–1914 | 2012 | |

| — | Charles "Chief" Bender | P | 1903–1914 | 2014 | |

| — | Herb Pennock | P | 1912–1915 | 2014 | Elected mainly on his performance with New York Yankees |

| — | By Saam | Broadcaster | 1938–1954 | 2014 | |

| 4, 7, 26 | Bob Johnson | LF | 1933–1942 | 2017 | |

| — | Home Run Baker | 3B | 1908–1914 | 2019 | |

Team captains

edit- 6 Sal Bando, 3B, 1969–1976

Season-by-season records

editThe records of the Athletics' last ten seasons in Major League Baseball are listed below.

| Season | Wins | Losses | Win % | Place | Playoffs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 68 | 94 | .420 | 5th in AL West | |

| 2016 | 69 | 93 | .426 | 5th in AL West | |

| 2017 | 75 | 87 | .463 | 5th in AL West | |

| 2018 | 97 | 65 | .599 | 2nd in AL West | Lost ALWC vs. New York Yankees, 7–2 |

| 2019 | 97 | 65 | .599 | 2nd in AL West | Lost ALWC vs. Tampa Bay Rays, 5–1 |

| 2020 | 36 | 24 | .600 | 1st in AL West | Lost ALDS vs. Houston Astros, 3–1 |

| 2021 | 86 | 76 | .531 | 3rd in AL West | |

| 2022 | 60 | 102 | .370 | 5th in AL West | |

| 2023 | 50 | 112 | .309 | 5th in AL West | |

| 2024 | 69 | 93 | .426 | 4th in AL West | |

| 10-Year Record | 707 | 811 | .466 | — | — |

| All-Time Record | 9,329 | 9,859 | .486 | — | — |

Philadelphia

editKansas City

editOakland

edit- Oakland Coliseum (1968–2024)

- Cashman Field in Las Vegas, Nevada (April 1996 for six games due to renovations at Oakland Coliseum)

Roster

edit| 40-man roster | Non-roster invitees | Coaches/Other | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pitchers

|

Catchers

Infielders

Outfielders

Designated hitters

|

|

Manager Coaches

Restricted list 34 active, 0 inactive, 0 non-roster invitees 7-, 10-, or 15-day injured list | |||

Minor league affiliations

editThe Athletics farm system consists of six minor league affiliates.[82]

| Class | Team | League | Location | Ballpark | Affiliated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triple-A | Las Vegas Aviators | Pacific Coast League | Summerlin, Nevada | Las Vegas Ballpark | 2019 |

| Double-A | Midland RockHounds | Texas League | Midland, Texas | Momentum Bank Ballpark | 1999 |

| High-A | Lansing Lugnuts | Midwest League | Lansing, Michigan | Jackson Field | 2021 |

| Single-A | Stockton Ports | California League | Stockton, California | Banner Island Ballpark | 2005 |

| Rookie | ACL Athletics | Arizona Complex League | Mesa, Arizona | Fitch Park | 1988 |

| DSL Athletics | Dominican Summer League | Boca Chica, Santo Domingo | Juan Marichal Complex | 1989 |

Radio and television

editAs of the 2020 season, the Athletics have had 14 radio homes.[83] The Athletics' flagship radio station is KNEW and the team has a free live 24/7 exclusive A's station branded as A's Cast to stream the radio broadcast within the Athletics market and other A's programming via iHeartRadio.[84] Going into the 2020 season, the Athletics had a deal with TuneIn for A's Cast and no flagship radio station in the Bay Area but changed their plans due to the COVID-19 pandemic keeping fans from attending games.[85] The announcing team features Ken Korach and Vince Cotroneo.

Television coverage is exclusively on NBC Sports California. Some A's games air on an alternate feed of NBCS, called NBCS Plus, if the main channel shows a Sacramento Kings or San Jose Sharks game at the same time. On TV, Jenny Cavnar covers play-by-play, and Dallas Braden provides color commentary. Some games would feature Chris Caray on play-by-play; Caray is a fourth-generation baseball announcer that included great-grandfather Harry Caray, grandfather Skip Caray, and father Chip Caray.

In popular culture

editThe 2003 Michael Lewis book Moneyball chronicles the 2002 Oakland Athletics season, with a focus on Billy Beane's economic approach to managing the organization under significant financial constraints. Beginning in June 2003, the book remained on The New York Times Best Seller list for 18 consecutive weeks, peaking at number 2.[86][87] In 2011, Columbia Pictures released a film adaptation based on Lewis' book, which featured Brad Pitt playing the role of Beane. On September 19, 2011, the U.S. premiere of Moneyball was held at the Paramount Theatre in Oakland, which featured a green carpet for attendees to walk, rather than the traditional red carpet.[88]

The blog that spawned the full-fledged popular sports blog site SBNation was dedicated to the Oakland Athletics.[89][90]

Eric Shaun Lynch, a former member of The Howard Stern Show's Wack Pack who went by the name "Eric the Actor" (and previously, "Eric the Midget"), was a huge fan of the Athletics and would occasionally talk about them on Stern's show. Following his death in September 2014, the team broadcasters offered a tribute by using Lynch's signature sign off "bye for now" at the end of an Athletics game broadcast. During the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, when American baseball teams were using cutouts of fans to show solidarity in their absence, the Athletics placed a cutout of Lynch among other cutouts of the team's fans.

See also

edit- Oakland Athletics award winners and league leaders

- List of Oakland Athletics first-round draft picks

- List of Oakland Athletics managers

- List of Oakland Athletics no-hitters

- List of Oakland Athletics Opening Day starting pitchers

- List of Oakland Athletics owners and executives

- List of Oakland Athletics team records

Explanatory notes

editReferences

edit- ^ "About Stomper". Athletics.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved August 21, 2018.

- ^ Clair, Michael (March 17, 2017). "Why do the A's wear green? You can thank Charlie Finley". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Archived from the original on January 7, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

Before Finley came on board, the then-Kansas City A's wore baseball's standard blue-and-red combination. In 1963, that all changed as Finley outfitted the team in glorious gold (Finley said it was the same shade the United States Naval Academy used) and kelly green for the very first time.

- ^ Clair, Michael (February 27, 2021). "The best baseball caps ever, by team". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

How many big league teams do you know that wear green and yellow, the most fantastic color scheme in the world? Exactly: Only one.

- ^ Drellich, Evan. "A's Brand Transition Guidelines". X. Retrieved November 4, 2024.

- ^ Oakland A’s to play in Sacramento’s Sutter Health Park beginning in 2025 ahead of move to Las Vegas

- ^ a b Perry, Dayn (November 4, 2024). "A's officially drop Oakland from name, won't add Sacramento as future plans remain at a standstill". CBS Sports. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ "Oakland Athletics Team History & Encyclopedia". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ Boxscore from Baseball-Reference.com "Wednesday, April 17, 1968, 7:46PM, Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum"

- ^ "After MLB approves A's Las Vegas move, a look at the history of relocation". Sports. CBS News. Associated Press. November 16, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ Gallegos, Martin (December 1, 2021), "How they came to be called the A's", MLB, retrieved October 29, 2024

- ^ "r/ClassicBaseball - Amazing 1866 Harper's Weekly woodcut engraving of the Brooklyn Atlantics and Philadelphia Athletics, from the National Association Of Base Ball Players league". reddit. May 24, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ^ "Logos and Mascots". MLB.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2016.

- ^ Odell, John. "The Elephant in the Room". BaseballHall.org. National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ "The A's celebrate KC roots with green and gold uniforms — and a mule named Charlie O". www.sportingnews.com. June 25, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2019.

- ^ Hill, Angela (May 22, 2007). "Mascots you don't see on sports sidelines". East Bay Times.

- ^ "Stomper's Place". Oakland Athletics. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016.

- ^ "Stomper: The Oakland A's Mascot". MLB.com. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ "Oakland A's to wear kelly green alternate jersey for Friday home games". MLB.com (Press release). MLB Advanced Media. January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ United Press International (January 30, 1979). "Yankees, Twins still dickering". St. Petersburg Times. p. 7c. Retrieved June 19, 2009.

- ^ "Cashman Field | Las Vegas 51s Cashman Field". Web.minorleaguebaseball.com. Archived from the original on April 22, 2008. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Leavitt, Parker (October 24, 2014). "Mesa's Hohokam Stadium ready for Oakland A's". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ^ "Oakland Athletics Spring Training". springtrainingonline.com. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ "Championship Plaza | Oakland Athletics". MLB.com.

- ^ "Oakland Coliseum timeline: 50 years of triumph and heartbreak at A's stadium". San Francisco Chronicle. July 19, 2021. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ "A's Stomping Ground". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media, LP. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ "Oakland A's to add new premium seating options at the Coliseum". MLB.com. MLB Advanced Media, LP. Retrieved June 2, 2024.

- ^ Frijoles, Billy (April 18, 2018). "Free Game, Free Vibes". Athletics Nation. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Hall, Alex (November 9, 2018). "Oakland A's announce more new seating options at Coliseum". Athletics Nation. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ "Giants vs. Athletics - Game Recap - July 21, 2018". ESPN.

- ^ Ross, By Matier &. (September 13, 2017). "A's want to build new ballpark next to Laney College in Oakland". Sfgate.

- ^ "Proposed site for A's ballpark falls through". USA Today. AP. December 6, 2017.

- ^ "A's settle on a ballpark site and a futuristic stadium". The Mercury News. November 28, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2018.

- ^ Uebelacker, Erik (June 7, 2023). "U.S. Rep Accuses Oakland A's, MLB of Acting in Bad Faith". The Daily Beast.

- ^ Dennis, Rob (December 30, 2011). "Fremont mayor Bob Wasserman dead at 77". The Argus (Fremont). Retrieved January 21, 2012.

- ^ "A's, Cisco reach ballpark deal". USA Today. November 9, 2006. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ "Full text of A's letter to Fremont". February 24, 2009.

- ^ "Plans for A's stadium in San Jose moving forward". USA Today. San Jose, California. Associated Press. June 16, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ "How the A's ballpark plans stack up". San Jose Mercury News. Bay Area News Group. August 24, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Seipel, Tracy (September 8, 2010). "75 Silicon Valley leaders endorse A's move to San Jose". San Jose Mercury News. Bay Area News Group. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Calcaterra, Craig (June 30, 2011). "In case you forgot, the Athletics are still in franchise limbo". HardballTalk. NBC Sports. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Koehn, Josh (July 12, 2011). "Selig Talks About A's Move to San Jose". San Jose Inside. Sanjoseinside.com. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Cotchett, Pitre & McCarthy, LLP (June 18, 2013), City of San Jose; City of San Jose as Successor Agency to the Redevelopment Agency of the City of San Jose; and the Sand Jose Diridon Development Authority, Plaintiffs, v. Office of the Commissioner of Baseball, an unincorporated association doing business as Major League Baseball; and Allan Huber "Bud" Selig, Defendants (PDF), U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2013, retrieved May 5, 2018

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "San Jose sues MLB over A's vote". San Francisco, California: ESPN. Associated Press. June 19, 2013. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ "San Jose loses appeal over A's move". San Francisco, California: ESPN. Associated Press. January 15, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ Egelko, Bob (October 5, 2015). "U.S. Supreme Court rejects San Jose's bid to lure Oakland A's". SFGate. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved August 19, 2015.

- ^ Stutz, Howard; Mueller, Tabitha (April 19, 2023). "Sources: Lombardo, lawmakers on board with planned $1 billion Las Vegas baseball stadium". The Nevada Independent. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ "Oakland A's close in on move to Las Vegas after signing land deal for stadium". The Guardian. April 20, 2023. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ Dubow, Josh (April 20, 2023). "Oakland A's purchase land for new stadium in Las Vegas". SFGate. Associated Press. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ "Oakland A's agree to purchase land near Las Vegas Strip". KGO-TV. April 20, 2023. Retrieved April 20, 2023.

- ^ "A's pivot to new site for Vegas baseball stadium, lowering public funding request". The Nevada Independent. May 9, 2023. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ Miller, Shannon (October 3, 2024). "Time to say goodbye to Tropicana Las Vegas, set for implosion this week". Las Vegas Weekly. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ Tisminezky, Ryan (September 24, 2024). "Tropicana Las Vegas receives implosion permit, asbestos abatement complete". KLAS. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ "Nevada governor signs A's stadium funding bill". KLAS. June 15, 2023. Archived from the original on September 21, 2023. Retrieved June 16, 2023.

- ^ Farkas, Brady (November 19, 2023). "An Interesting Nugget About the Oakland Athletics' Relocation to Las Vegas". Fastball. Retrieved November 23, 2023.

- ^ @Athletics (April 4, 2024). "Sutter Health Park in West Sacramento will host the A's for the 2025-27 seasons - ahead of the team's move to Vegas in 2028" (Tweet). Retrieved April 4, 2024 – via Twitter.

- ^ Cova, Ernesto (May 27, 2021). "15 biggest MLB rivalries of all time". bolavip.com. Retrieved January 13, 2022.

- ^ "Head-to-head record for Oakland Athletics against the listed opponents from 1997 to 2021". baseball-reference.com.

- ^ Goldberg, Ron (March 24, 2018). "Athletics Offer $20 Parking Discount to Giants Fans Who Yell 'Go A's' at Gates". Bleacher Report. Retrieved March 26, 2018.

- ^ "Athletics, Giants unveil Bay Bridge trophy". MLB.com.

- ^ "New Bay Bridge Opens Ahead of Schedule - NBC Bay Area". Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ "Last 2 Piers of the Old Bay Bridge Demolished". September 8, 2018.

- ^ "A's Take Bay Bridge Series with Another Walkoff Win over the Giants". July 22, 2018.

- ^ "Oakland A's, LA Angels: The Fight For The West". Bleacher Report.

- ^ Jenkins, Bruce. "A's-Angels rivalry 30 years in making / After decades, rivalry is heated". SFGate.

- ^ "Angels-Athletics is becoming a real rivalry". Los Angeles Times. August 29, 2014.

- ^ "A's vs. Angels: The Rivalry That Should Be (And Eventually Will)". September 10, 2012.

- ^ "2014 Promotional Schedule". Oakland Athletics. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 4, 2015.

- ^ Burgoyne, Tom (2004). Movin' on Up: Baseball and Philadelphia Then, Now, and Always. B B& A Publishers. p. 128. ISBN 0-9754419-3-0.

- ^ @Dsmoke34 (April 12, 2022). "@GlennRecon I have no idea what the A's are doing. At this point they can just retire the number with no celebratio…" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Miedema, Laurence (April 22, 2022). "A's Announce Date to Retire Former Ace Dave Stewart's No. 34". The Mercury News. Retrieved April 27, 2022.

- ^ "Oakland A's announce the Athletics Hall of Fame". August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Athletics Hall of Fame". MLB.com.

- ^ "A's announce five members of the Athletics Hall of Fame Class of 2022; fans can vote to help select final member". MLB.com.

- ^ "A's to Induct Ray Fosse into Athletics Hall of Fame in 2022". MLB.com.

- ^ "Giambi, Lansford among 5 to enter A's Hall of Fame Class in 2023". MLB.com.

- ^ "A's to Celebrate the Coliseum for the Remainder of 2024". April 5, 2024.

- ^ For photos of the A's Wall of Fame plaques, see Philadelphia A's Society Museum and Library Archived December 29, 2005, at the Wayback Machine webpage. Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society Archived September 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine official website. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Frank (February 22, 2011). "Demographics may doom the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2011.

- ^ For photos of the plaque, see Montella, Ernie (June 5, 2004). "Wall of Fame Day in Hatboro, Pennsylvania". Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Jordan, David M. "Vet Plaques Come to Hatboro". Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Oakland Athletics Minor League Affiliates". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved October 20, 2023.

- ^ "Oakland A's confirm split with radio flagship via Twitter". The Mercury News. October 13, 2018. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ San Francisco Chronicle [@sfchronicle] (July 30, 2020). "JUST IN: The Oakland A's - who had planned to provide streaming-only service for its audio broadcasts in the Bay Area - will partner with 960 AM radio station starting Friday. https://t.co/BE7zJ2pv6M" (Tweet). Retrieved December 31, 2020 – via Twitter.

- ^ "A's announce new radio partnerships for upcoming season". The Mercury News. February 15, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2019.

- ^ "The New York Times Best Seller List - June 22, 2003" (PDF). Hawes Publications. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ "The New York Times Best Seller List - September 23, 2003" (PDF). Hawes Publications. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ "Oakland shines for 'Moneyball' premiere". San Francisco Chronicle. September 20, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2014.

- ^ "The Evolution of Sports Blog Nation". Inc.com. August 20, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ "SB Nation United: What To Expect From The New Our Daily Bears". SBNation. September 20, 2012. Retrieved June 12, 2022.

Further reading

edit- Bergman, Ron. Mustache Gang: The Swaggering Tale of Oakland's A's. Dell Publishing Co., New York, 1973.

- Dickey, Glenn. Champions: The Story of the First Two Oakland A's Dynasties—and the Building of the Third. Triumph Books, Chicago, 2002. ISBN 1-57243-421-X

- Jordan, David M. The Athletics of Philadelphia: Connie Mack's White Elephants, 1901–1954. McFarland & Co., Jefferson NC, 1999. ISBN 0-7864-0620-8.

- Katz, Jeff. "The Kansas City A's & The Wrong Half of the Yankees." Maple Street Press, Hingham, Massachusetts, 2006. ISBN 978-0-9777436-5-0.

- Kuklick, Bruce. To Everything a Season: Shibe Park and Urban Philadelphia 1909–1976. Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1991. ISBN 0-691-04788-X.

- Lewis, Michael. Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game. W. W. Norton & Co., Inc., New York, 2003. ISBN 0-393-05765-8.

- Markusen, Bruce. Baseball's Last Dynasty: Charlie Finley's Oakland A's. Master Press, Indianapolis, 1998.

- Peterson, John E. The Kansas City Athletics: A Baseball History 1954–1967. McFarland & Co., Jefferson NC, 1999. ISBN 0-7864-1610-6.

- Slusser, Susan. 100 Things A's Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die. Triumph Books, Chicago, 2015. ISBN 978-1629370682.

External links

edit- Athletics official website

- Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society

- Oakland Athletics Franchise History Archived November 4, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Sports E-Cyclopedia

- Oakland A's prospect information

| Awards and achievements | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | World Series champions Philadelphia Athletics 1910–1911 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Philadelphia Athletics 1913 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Philadelphia Athletics 1929–1930 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Oakland Athletics 1972–1974 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | World Series champions Oakland Athletics 1989 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Philadelphia Athletics 1902 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Philadelphia Athletics 1905 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Philadelphia Athletics 1910–1911 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Philadelphia Athletics 1913–1914 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Philadelphia Athletics 1929–1931 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Oakland Athletics 1972–1974 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | American League champions Oakland Athletics 1988–1990 |

Succeeded by |