Pharnaces II of Pontus (‹See Tfd›Greek: Φαρνάκης; about 97–47 BC) was the king of the Bosporan Kingdom and Kingdom of Pontus until his death. He was a monarch of Persian and Greek ancestry. He was the youngest child born to King Mithridates VI of Pontus from his first wife, his sister Queen Laodice.[1] He was born and raised in the Kingdom of Pontus and was the namesake of his late double great grandfather Pharnaces I of Pontus. After his father was defeated by the Romans in the Third Mithridatic War (73–63 BC) and died in 63 BC, the Romans annexed the western part of Pontus, merged it with the former Kingdom of Bithynia and formed the Roman province of Bithynia and Pontus. The eastern part of Pontus remained under the rule of Pharnaces as a client kingdom until his death.

| Farnaces II | |

|---|---|

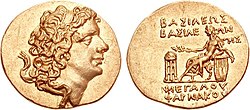

Gold stater of Pharnaces as Obv: head of Pharnakes diademed. Rev: Appolo seated behind tripus, legend: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΦΑΡΝΑΚΟΥ. | |

| King of Pontus | |

| Reign | 63–47 BC |

| Predecessor | Mithridates VI |

| Successor | Darius of Pontus |

| King of the Bosporus | |

| Reign | 63–47 BC |

| Predecessor | Mithridates I |

| Successor | Mithridates II |

| Born | c. 97 BC |

| Died | 47 BC |

| Issue | |

| Dynasty | Mithridatic |

| Father | Mithradates VI Eupator |

| Mother | Laodice (sister of Mithridates VI) |

Rebellion against his father

editPharnaces II was raised as his father's successor and treated with distinction. However, little is known of his youth from ancient writers and find him first mentioned after Mithridates VI was defeated by the Roman general Pompey during the Third Mithridatic War. Cassius Dio and Florus wrote that Mithridates planned to attack Italy by crossing Scythia and the River Danube, according to the former, or through Thrace, Macedonia and the rest of Greece, according to the latter.[2][3] Appian also wrote about a planned invasion of Italy, but did not mention any routes. The scale of the expedition put many of his soldiers off. Castor of Phanagoria and his city rebelled. Many of the castles he had occupied on the eastern shores of the Black sea also rebelled. This was followed by a rebellion by Pharnaces.[4]

Appian wrote that Pharnaces conspired against his father. The conspirators were captured and tortured. However, Mithridates was persuaded to spare Pharnaces. The latter feared his father's anger and knew that Mithridates’ soldiers were not keen on the expedition. He went to Roman deserters who were encamped near Mithridates to highlight the dangers of the expedition and to encourage them to desert his father. He sent other people to do the same in other camps. In the morning there was an uprising. Mithridates fled and Pharnaces was proclaimed king by the troops. Mithridates sent messengers to ask his son for permission to withdraw safely. When they did not return, he tried to poison himself. However, it did not have an effect on him because he was used to taking small portions of poison as a protection against poisoners. Thus, he got an officer to kill him. Pharnaces sent his body to Pompey together with an emissary who offered submission and hostages. Pharnaces asked to be allowed to rule his father's kingdom or the Cimmerian Bosporus. Pompey named him a friend and ally of the Romans. He gave him the Cimmerian Bosporus except for Phanagoria, which was to be independent as a reward for having been the first to rebel against Mithridates.[5]

Cassius Dio also gave an account of the rebellion of Pharnaces. He wrote that as Mithridates' position became weaker, some of his associates became disaffected and some of the soldiers mutinied. Mithridates suppressed this before it caused troubles and punished some people, including some of his sons, just of the basis of suspicions. Pharnaces was afraid of his father and plotted against him. He also hoped to receive his kingdom from the Romans if he defected. Mithridates sent some guards to arrest him, but he won them over. He then marched against his father who was in Panticapaeum. Mithridates sent some soldiers ahead to confront him, but these were also won over. Panticapaeum surrendered to Pharnaces and he had his father put to death. Mithridates took some poison, but this did not kill him as he was used to take large doses of poison as an antidote. He was weakened and did not manage to take his life. He died fighting some men who had reached him. Pharnaces had his body embalmed and sent it to Pompey as proof that he had killed him. He also offered him his surrender. Pompey granted Pharnaces the kingdom of Bosporus and ‘enrolled him as a friend and ally’ of Rome.[6]

In contrast with Appian and Cassius Dio, Festus wrote that "Pompey imposed a king, Aristarchus, on the [Cimmerian] Bosphorians and Colchians."[7]

Appian wrote that Pharnaces besieged Phanagoria and the towns neighboring the Bosporus. Short of food, the Phanagoreans had to come out and fight. They were defeated. Pharnaces did not harm them. He made friends with them, took hostages, and left. According to Appian, this was not long before he made his attacks in Anatolia.[8]

Invasions in Anatolia and defeat of Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus

editIn 49 BC, a civil war (Caesar's Civil War) broke out between Gaius Julius Caesar and the Roman senate whose forces were led by Pompey. Caesar defeated Pompey in Greece in 47 BC, went to Egypt and was besieged in Alexandria of Egypt. Pharnaces took advantage of this to invade part of Anatolia.

Cassius Dio wrote that Pharnaces seized Colchis easily. He took advantage of the absence of Deiotarus, the king of Galatia and Lesser Armenia, to seize Lesser Armenia, part of Cappadocia, and some cities in the Roman province of Bithynia and Pontus which had formerly been part of the Kingdom of Pontus and had been assigned to the Bithynia district of that province. Caesar, who still had trouble in Egypt, sent Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus to take charge of the Roman legions in Roman province of Asia. Domitius added the forces of Deiotarus and Ariobarzanes III, the king of Cappadocia, to his forces. He advanced towards Pharnaces, who had seized Nicopolis, a city in Lesser Armenia. Pharnaces sent envoys to negotiate an armistice. Domitius rejected this, attacked, was defeated and withdrew back to Asia. Pharnaces then conquered the rest of Pontus. He seized the city of Amisus in Pontus, plundered it and killed all its men of military age. He next advanced towards Bithynia and the Roman province of Asia, but stopped because he learnt that Asander, whom he had left in charge back home in the Cimmerian Bosporus had revolted.[9]

Plutarch wrote that Pharnaces defeated Domitius, who withdrew from Pontus. He then occupied Bithynia and Cappadocia. After that he set his eyes on Lesser Armenia. He incited the princes and tetrarchs of that territory to revolt.[10] In his book on the Civil Wars, Appian only mentioned that Pharnaces seized the city of Amisus in Pontus, sold its inhabitants into slavery and made the boys eunuchs.[11] However, in his book on the Mithridatic Wars, he wrote that Pharnaces seized Sinope in Pontus and wanted to also take Amisus (further east in Pontus) and that it was for this reason that he made war on Domitius. However, the rebellion of Asander drew him away from Roman Asia.[12] Florus only mentioned Cappadocia and wrote that Pharnaces relied on Roman internal feuds rather that his valour to invade it.[13]

Cicero wrote that Deiotarus also supported Domitius financially and sent him money to Ephesus. He sent him money a third time by auctioning some of his property to raise it.[14]

The Alexandrine War[15] gives more details about the interactions between Domitius and Pharnaces. King Deiotarus went to see to Calvinus to beg him not to allow Lesser Armenia or Cappadocia, to be overrun by Pharnaces, otherwise he could not pay the money he had promised to Caesar. Domitius considered this money to be indispensable for the military expenses and felt that it would be shameful if the kingdoms of the Roman allies and friends were to be seized by Pharnaces. Thus, he sent envoys to Pharnaces to ask him to withdraw from Armenia and Cappadocia, believing that this would have greater impact than advancing on him with an army. He had sent two legions to Caesar for his war in Alexandria. He had at his disposal only one Roman legion, the 36th, and two legions provided by Deiotarus which were equipped and trained the Roman way. He had 1000 cavalry and received the same number of cavalry from Ariobarzanes II. A lieutenant was sent to Cilicia to gather auxiliary troops. A legion was also raised hastily and in an improvised manner in Pontus. These forces assembled at Comana on Pontus.

Pharnaces sent a reply in which he said that he had withdrawn from Cappadocia but had recovered Lesser Armenia which was his inheritance from his father and that, regarding this, he would wait for Caesar's reply and comply with what he decided. Domitius thought that he had withdrawn from Cappadocia out of necessity rather than his free will because he heard about the two legions sent to Caesar and thought that if they advanced towards Armenia, he could defend it better if he stayed in Lesser Armenia. Domitius insisted that Pharnaces should withdraw from Lesser Armenia, too, and marched towards Armenia through a wooded ridge which formed the border between Cappadocia and Armenia and extended into Lesser Armenia. This was higher ground in which he could not be attacked. He could also get supplies from Cappadocia from here. Pharnaces sent several embassies for peace talks, which were rejected. Domitius encamped near Nicopolis in Lesser Armenia. There was a narrow defile nearby. Pharnaces set up an ambush with selected infantrymen and all his cavalry. He got the local farmers to graze their cattle at various points in the gorge so that Domitius would not suspect an ambush and to encourage his troops to scatter to plunder the cattle. He also kept sending envoys for further deceit. However, this resulted in Domitius staying in his camp. Pharnaces was worried that his ambush might be discovered and recalled his troops to camp.

Domitius set off for Nicopolis and encamped by the town. Pharnaces lined up for battle, but Domitius did not take this up and completed the fortification of his camp. Pharnaces intercepted dispatches from Caesar to Domitius and learnt that the latter was still in difficulty in Alexandria and was asking Domitius to send him reinforcements and to advance closer to Alexandria via Syria. Pharnaces thought that Domitius was about to withdraw. He dug two trenches on the path which would be easier to do battle. He placed his infantry between the trenches and the cavalry, which far outnumbered the Roman cavalry, on the flanks, outside the trenches. Domitius thought that it would not be safe to withdraw. He lined up for battle near his camp, posting the legions of Deioratus in the centre, the 36th on the right and the one from Pontus in a narrow line supported by the remaining cohorts.

In the battle the 36th attacked the enemy cavalry successfully and advanced close to the city walls, crossed the trench and attacked the enemy rear. The Pontic legion tried to go cross the trench to attack the enemy's exposed flank. However, while crossing, it was pinned down and overwhelmed. The legions of Deiotarus hardly offered any resistance. Pharnaces, having won in the centre and the right turned on the 36th and surrounded it. This legion formed a circle and, while fighting, it withdrew to a hill, losing only 250 men. Domitius retreated to Asia via Cappadocia. Pharnaces occupied Pontus, took many towns by storm, plundered the property of Roman and Pontic citizens and meted out harsh punishments on the youth. He boasted that he had recovered the kingdom of his father and thought that Caesar would be defeated in Alexandria.[16]

Defeat by Gaius Julius Caesar

editCassius Dio wrote that after escaping the siege of Alexandria and defeating Ptolemy XIII of Egypt, Caesar rushed to Armenia. Pharnaces, who was heading north to deal with the rebellion of Asander, turned back to meet Caesar. He was worried about the speed with which he was advancing. He sent envoys to Caesar to see if he could make terms with him, reminding him that he had never cooperated with Pompey. He hoped for a truce and that Caesar would proceed to deal with urgent matters in Italy and Africa, after which he could resume his war. Caesar suspected this and treated two embassies well, so that Pharnaces would hope for peace and he could attack him by surprise. However, he reproached Pharnaces when a third embassy arrived. On the same day he engaged in battle. There was confusion caused by the cavalry and scythe-bearing chariots of the enemy, but then Caesar won.[17]

According to Plutarch, Caesar learned about the defeat of Domitius by Pharnaces and that Pharnaces was taking advantage of this to occupy Bithynia and Cappadocia and hoped to gain Lesser Armenia by instigating revolts by the local princes and tetrarchs when he left Egypt and was crossing Asia. Caesar advanced against him with three legions. He defeated Pharnaces in the Battle of Zela (see Battle of Zela (47 BC)), annihilated his army and drove him out of Pontus.[10] Suetonius wrote that Caesar proceeded via Syria and defeated Pharnaces “in a single battle within five days after his arrival and four hours after getting sight of him.”[18] Frontinus wrote that Caesar drew up his battle line on a hill. This made victory easy as his men could throw darts at the enemy and put them to flight quickly.[19] Appian wrote that when Caesar was within 200 stades (c. 3 km, 1.9 miles), Pharnaces sent envoys to negotiate peace. They brought a golden crown and offered him Pharnaces’ daughter in marriage. Caesar walked in front of his army and talked to the envoys until he reached the camp of Pharnaces. He then said, "Why should I not take instant vengeance on this parricide?" He jumped on his horse and started the battle, killing many of the enemy, even though he had only 100 cavalry.[11]

Plutarch and Appian wrote that Caesar wrote the word ‘veni, vidi vici’. These are usually translated as ‘I came, I saw, I conquered.’ Plutarch said that Caesar wrote these words to announce “the swiftness and fierceness of this battle to one of his friends at Rome, Amantius”[10] Florus remarked that Caesar crushed Pharnaces “like a thunderbolt which in one and the same moment has come, has struck and has departed. Caesar's boast was no vain one when he said that the enemy was defeated before he was seen.”[13] Appian wrote that Caesar “exclaimed, "O fortunate Pompey, who was considered and named the Great for warring against such men as these in the time of Mithridates, the father of this man."[11] Suetonius wrote that after this victory Caesar often remarked “on Pompey's good luck in gaining his principal fame as a general by victories over such feeble foemen.”[18]

Caesar then sailed to Syria. There he received news of political trouble in Rome. His presence in Rome was urgent. Caesar wanted to quickly sort out affairs in Syria, Cilicia and Asia and deal with Pharnaces first. He visited the more important states in Syria to settle local disputes. He then sailed to Cilicia and summoned all the states of the province and settled local affairs. In Cappadocia he prevented disputes between Ariobarzanes II of Cappadocia and his brother Ariarathes by giving the latter part of Lesser Armenia as a vassal of the former. In Galatia, close to the border with Pontus, he ordered Deiotarus to provide a Galatian legion. This was a modest and inexperienced force. Besides this legion Caesar had the veteran 6th legion he had brought from Alexandria, which had lost many men in previous combats and was reduced to 1,000 men, and two legions which had fought with Domitius.

Caesar received envoys from Pharnaces who asked him not to start hostilities and said that Pharnaces would obey his instructions. Caesar replied that he would be fair if Pharnaces kept his promise and ordered him to withdraw from Pontus and make restitutions to Rome's allies and Roman citizens. He would accept his gifts (Pharnaces had sent him a golden crown) only after he had done what he was asked. Pharnaces promised to comply and, hoping that Caesar would trust him as he had to return to Rome in a hurry, he asked for a later date for his withdrawal and proposed agreements as a delaying tactic. Caesar understood this and decided to act swiftly and catch him by surprise.

Pharnaces was encamped near Zela, in Pontus, which was in a plain. Around the town there many hills and valleys. A very high hill, three miles from the town, was linked to it by paths on higher ground. Pharnaces had repaired the rampart of the camp his father had built when he posted his forces there during the Third Mithridatic War. Caesar encamped five miles away. He ordered his men to collect material for a rampant. The following night he left his camp with all his troops and occupied a spot nearer the enemy camp which was the place where Pharnaces’ father defeated a Roman army. This caught the enemy by surprise. Caesar got slaves to bring the material for the rampart, which the soldiers begun to build.

Pharnaces lined up all his forces in front of Caesar's camp, on the opposite side of the valley. In order not to delay the construction work, Caesar drew up only his first line in front of it. Pharnaces began to march down the steep ravine which was unsuitable for military action. He then placed his force in battle array and climbed the steep hillside. His foolhardiness was unexpected and caught Caesar unprepared. He recalled his men from their work and formed a battle line. They panicked because they were not in regular formation. Pharnaces' scythed chariots threw the men into confusion. However, the chariots were quickly overwhelmed by a mass of missiles. Then the enemy infantry engaged, and heavy fighting started. The 6th legion on the right wing pushed the enemy back down the slope. So did, but more slowly, the left wing and the centre. The uneven ground made this easier. Many of the enemy were trampled over by falling comrades and many were killed. The Romans seized the enemy camp and the entire force was killed or captured. Pharnaces escaped. This victory filled Caesar 'with incredible delight' because he brought a very serious war to an end quickly, won an easy victory and resolved a very difficult situation.[20]

Death

editAfter his defeat, Pharnaces fled to Sinope with 1,000 cavalry. Caesar, who was too busy to follow him, sent Domitius after him. Pharnaces surrendered Sinope. Domitius agreed to let him leave with his cavalrymen, but killed his horses. Pharnaces sailed to the Cimmerian Bosporus, intending to recover it from Asander. He collected a force of Scythians and Sarmatians, and captured Theodosia and Panticapaeum. In response, Asander attacked and defeated Pharnaces. He was defeated because he was short of horses and his men were not used to fighting on foot. Pharnaces was killed in this battle.[12] Strabo wrote that Asander then took possession of the Bosporus.[21] In response, Julius Caesar gave a tetrarchy in Galatia and the title of king to Mithridates of Pergamon. This Mithridates became Mithridates I of the Bosporus. Caesar also allowed him to wage war against Asander and conquer the Cimmerian Bosporus because he had shown cruelty to his friend Pharnaces.[17]

Pharnaces II was fifty years old at his death and had been the king of the Cimmerian Bosporus fifteen years.[12]

Coinage

editGold and silver coins have survived from his reign dating from 55 BC to 50 BC.[22] An example displays a portrait of Pharnaces II on the obverse. On the reverse, it displays Apollo semi-draped, seated on a lion-footed throne, holding a laurel branch over a tripod. Apollo's left elbow is resting on a cithara at his side. On top and between Apollo is inscribed his royal title in Greek: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΦΑΡΝΑΚΟΥ, which means of King of Kings Pharnaces the Great.

Marriage, issue and succession

editIn the early 1st century BC Mithridates VI made an alliance with the Sarmatian tribes,[23] and, probably through this alliance, Pharnaces (possibly sometime after 77 BC) married an unnamed Sarmatian noblewoman.[24] She may have been a princess, a relative of a ruling Sarmatian monarch or an influential aristocrat of some stature. His Sarmatian wife bore Pharnaces a son, Darius, a daughter, Dynamis, and a son, Arsaces. The names that Pharnaces II gave his children are a representation of his Persian and Greek heritage and ancestry. His sons were made Pontic kings for a time after his death, by Roman triumvir Mark Antony. His daughter and her family succeeded him as ruling monarchs of the Bosporan Kingdom. Pharnaces II through his daughter would have further descendants ruling the Bosporan Kingdom.

Pharnaces II in opera

editThe 18th-century librettist Antonio Maria Lucchini crafted a libretto based on incidents from the life of Pharnaces II that was originally set by Antonio Vivaldi in 1727 under the title Farnace. Based on the number of revivals of it that were staged, it must be counted as one of Vivaldi's most successful operas. A few later composers also set Lucchini's libretto, among them Josef Mysliveček, with Farnace of 1767. Pharnaces II also appears in Mitridate by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Mayor, The Poison King: the life and legend of Mithradates, Rome’s deadliest enemy p.xviii

- ^ Casius Dio, Roman History, 37.11

- ^ Florus, Epitome of Roman History, 1.40.16

- ^ Appian, The Mithridatic War, 108-109

- ^ Appian, The Mithridatic War, 110-11, 113-14

- ^ Casius Dio, Roman History, 37.12-14

- ^ Festus, summary of Roman history, 16

- ^ Appian, The Mithridatic Wars, 120

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History, 42.45-46

- ^ a b c Plutarch, The life of Caesar, 50

- ^ a b c Appian, The Civil Wars, 2.91

- ^ a b c Appian, The Mithridaric Wars, 120-21

- ^ a b Florus, The Epitome of Roman History, 2.61

- ^ Cicero, For King Deiotarius, 14

- ^ This book was attached to Julius Caesar's Commentaries of the Civil War, but was not written by him. It was probably written by Histius

- ^ Caesar, The Alexandrian War, 34-41

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History, 42.47

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Life of Julius Caesar, 35.2

- ^ Frontinus, Stratagems, 2.3

- ^ Julius Caesar, The Alexandrine War, 65-77

- ^ Strabo. Geography, 4.3

- ^ "Ira and Larry Goldberg World and Ancient Coin Auction : Coin Collecting News". Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- ^ "Livius.org, Articles on Ancient History: Sarmatians". Archived from the original on 2014-05-07. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- ^ Mayor, The Poison King: the life and legend of Mithradates, Rome’s deadliest enemy p.362

Sources

edit- Primary sources

- Appian, The Civil Wars, Penguin Classics, new edition, 1996;ISBN 978-0140445091

- Appian, The Foreign Wars, The Mithridatic Wars, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014; ISBN 978-1503114289

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, vol. 4, Books 41-45 (Loeb Classical Library), Loeb, 1989; ISBN 978-0674990739

- Julius Caesar, The Civil War: Together with the Alexandrian War, the African War, and the Spanish War, Penguin Classics, new impression edition, 1976;

- Mayor, A., The Poison King: the life and legend of Mithradates, Rome's deadliest enemy, Princeton University Press, 2009

- Secondary sources

- Gabelko. O.L., The Dynastic History of the Hellenistic Monarchies of Asia Minor According to Chronography of George Synkellos in Højte, J.M, (ed.), Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom, Black Sea Studies, Vol. 9, Aarhus University Press; ISBN 978-8779344433 [1]

- Smith, W (ed.) Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities: Pharnaces II, 1870

Further reading

edit- Coşkun, Altay (2019). "The Course of Pharnakes II's Pontic and Bosporan Campaigns in 48/47 B.C.". Phoenix. 73 (1/2): 86–113. doi:10.7834/phoenix.73.1-2.0086. hdl:10012/18088. JSTOR 10.7834/phoenix.73.1-2.0086. S2CID 239411551.

External links

edit- Livius.org, Articles on Ancient History: Sarmatians [2] Archived 2014-05-07 at the Wayback Machine