The parotid gland is a major salivary gland in many animals. In humans, the two parotid glands are present on either side of the mouth and in front of both ears. They are the largest of the salivary glands. Each parotid is wrapped around the mandibular ramus, and secretes serous saliva through the parotid duct into the mouth, to facilitate mastication and swallowing and to begin the digestion of starches. There are also two other types of salivary glands; they are submandibular and sublingual glands.[1] Sometimes accessory parotid glands are found close to the main parotid glands.[2]

| Parotid gland | |

|---|---|

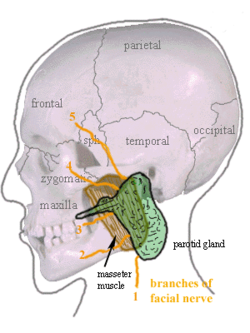

Location of the left parotid gland in humans (shown in green). | |

Image | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Salivary glands |

| System | Digestive system |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | glandula parotidea |

| MeSH | D010306 |

| TA98 | A05.1.02.003 |

| TA2 | 2800 |

| FMA | 59790 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Etymology

editThe word parotid literally means "beside the ear". From Greek παρωτίς (stem παρωτιδ-) : (gland) behind the ear < παρά - pará : in front, and οὖς - ous (stem ὠτ-, ōt-) : ear.

Structure

editThe parotid glands are a pair of mainly serous salivary glands located below and in front of each ear canal, draining their secretions into the vestibule of the mouth through the parotid duct.[3] Each gland lies behind the mandibular ramus and in front of the mastoid process of the temporal bone. The gland can be felt on either side, by feeling in front of each ear, along the cheek, and below the angle of the mandible.[4]

The parotid duct, a long excretory duct, emerges from the front of each gland, superficial to the masseter muscle. The duct pierces the buccinator muscle, then opens into the mouth on the inner surface of the cheek, usually opposite the maxillary second molar. The parotid papilla is a small elevation of tissue that marks the opening of the parotid duct on the inner surface of the cheek.[4]

The gland has four surfaces – superficial or lateral, superior, anteromedial, and posteromedial. The gland has three borders – anterior, medial, and posterior. The parotid gland has two ends – a superior end in the form of a small superior surface and an inferior end (apex).

A number of different structures pass through the gland. From lateral to medial, these are:

- Facial nerve

- Retromandibular vein

- External carotid artery

- Superficial temporal artery

- Branches of the great auricular nerve

- Maxillary artery

Sometimes accessory parotid glands are found as an anatomic variation. These are close to the main glands and consist of ectopic salivary gland tissue.[2]

Capsule of parotid gland

A capsule of the parotid gland is formed from the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia. It is supplied by the great auricular nerve. The fascia splits to enclose the gland. This splitting occurs between the angle of the mandible and the mastoid process. The superficial lamina (parotidomassetric fascia) is thick and is attached to the zygomatic arch. The deep lamina is thin and is attached to the styloid process, tympanic plate, and the ramus of the mandible. The part of the deep lamina extending between the styloid process and the mandible is thickened to form a stylomastoid ligament. The stylomandibular ligament separates the parotid gland from the superficial lobe of the submandibular gland. [citation needed]

Relations

edit- Superficial or lateral relations: The gland is situated deep to the skin, superficial fascia, superficial lamina of investing layer of deep cervical fascia, and great auricular nerve (anterior ramus of C2 and C3).

- Anteromedial relations: The gland is situated posterolaterally to the mandibular ramus, masseter, and medial pterygoid muscles. A part of the gland may extend between the ramus and medial pterygoid, as the pterygoid process. Branches of the facial nerve and parotid duct emerge through this surface.

- Posteromedial relations: The gland is situated anterolaterally to mastoid process of temporal bone with its attached sternocleidomastoid and digastric muscles, styloid process of temporal bone with its three attached muscles (stylohyoid, stylopharyngeus, and styloglossus) and carotid sheath with its contained neurovasculature (internal carotid artery, internal jugular vein, and 9th, 10th, 11th, and 12th cranial nerves).

- Medial relations: The parotid gland comes into contact with the superior pharyngeal constrictor muscle at the medial border, where the anteromedial and posteromedial surfaces meet. Hence, a need exists to examine the fauces in parotitis.

The facial nerve (CN VII) splits into its branches within the parotid gland, thus forming its parotid plexus. Nerves of this plexus then pass through the parotid gland without innervating the gland itself.[5]

Vasculature

editArterial supply

The external carotid artery and its terminal branches within the gland, namely, the superficial temporal and the maxillary artery, also the posterior auricular artery supply the parotid gland.[citation needed]

Venous drainage

Venous return is to the retromandibular veins.[citation needed]

Lymphatic drainage

The gland is mainly drained into the preauricular or parotid lymph nodes which ultimately drain to the deep cervical chain.[citation needed]

Nerve supply

editThe parotid gland receives both sensory and autonomic innervation.

Sympathetic

The cell bodies of the preganglionic sympathetic fibres that supply the gland usually lie in the lateral horns of upper thoracic spinal segments (T1-T3). [citation needed] Postganglionic sympathetic fibers from superior cervical ganglion reach the gland by passing along the external carotid artery and middle meningeal artery. They act to cause vasoconstriction.[6]: 359–360

Parasympathetic

Preganglionic parasympathetic fibers for the parotid gland arise in the brainstem in the inferior salivatory nucleus, and leave the brain in the glossopharyngeal nerve (CN IX), then pass in the tympanic nerve to the tympanic plexus, then from the tympanic plexus in the lesser petrosal nerve to the otic ganglion where they synapse. Postganglionic (post-synaptic) fibers from the ganglion then "hitch-hike" along the auriculotemporal nerve to reach the parotid gland.[7][8]: 255

Sensory

General sensory innervation to the parotid gland and its capsule is provided by the auriculotemporal nerve.[9]

Histology

editThe gland has a capsule of its own of dense connective tissue but is also provided with a false capsule by the investing layer of the deep cervical fascia. The fascia at the imaginary line between the angle of the mandible and the mastoid process splits into a superficial and a deep lamina to enclose the gland. The risorius is a small muscle embedded with this capsule substance.

The gland has short, striated ducts and long, intercalated ducts.[10] The intercalated ducts are also numerous and lined with cuboidal epithelial cells and have lumina larger than those of the acini. The striated ducts are also numerous and consist of simple columnar epithelium, having striations that represent the infolded basal cell membranes and mitochondria.[8]: 273

Though the parotid gland is the largest, it provides only 25% of the total salivary volume. The serous cell predominates in the parotid, making the gland secrete a mainly serous secretory product.[10]

The parotid gland also secretes salivary alpha-amylase (sAA), which is the first step in the decomposition of starches during mastication. It is the main exocrine gland to secrete this. It breaks down amylose (straight chain starch) and amylopectin (branched starch) by hydrolyzing alpha 1,4 bonds. Additionally, the alpha amylase has been suggested to prevent bacterial attachment to oral surfaces and to enable bacterial clearance from the mouth.[11]

Development

editThe parotid salivary glands appear early in the sixth week of the prenatal development and are the first major salivary glands formed. The epithelial buds of these glands are located on the inner part of the cheek, near the labial commissures of the primitive mouth (from ectodermal lining near angles of the stomodeum in the 1st/2nd pharyngeal arches; the stomodeum itself is created from the rupturing of the oropharyngeal membrane at about 26 days.[12]) These buds grow up posteriorly toward the otic placodes of the ears and branch to form solid cords with rounded terminal ends near the developing facial nerve. Later, at around 10 weeks of prenatal development, these cords are canalized and form ducts, with the largest becoming the parotid duct for the parotid gland. The rounded terminal ends of the cords form the acini of the glands. Secretion by the parotid glands via the parotid duct begins at about 18 weeks of gestation. Again, the supporting connective tissue of the gland develops from the surrounding mesenchyme.[10]

Clinical significance

editParotitis

editInflammation of one or both parotid glands is known as parotitis. The most common cause of parotitis is mumps. Widespread vaccination against mumps has markedly reduced the incidence of mumps parotitis. The pain of mumps is due to the swelling of the gland within its fibrous capsule.[3]

Apart from viral infection, other infections, such as bacterial, can cause parotitis (acute suppurative parotitis or chronic parotitis). These infections may cause blockage of the duct by salivary duct calculi or external compression. Parotid gland swellings can also be due to benign lymphoepithelial lesions[clarification needed] caused by Mikulicz disease and Sjögren syndrome. Swelling of the parotid gland may also indicate the eating disorder bulimia nervosa, creating the look of a heavy jaw line. With the inflammation of mumps or obstruction of the ducts, increased levels of the salivary alpha amylase secreted by the parotid gland can be detected in the blood stream.

Mumps

editMumps is seen to be a common cause of parotid gland swelling – 85% of cases occur in children younger than 15 years. The disease is highly contagious and spreads by airborne droplets from salivary, nasal, and urinary secretions.[13] Symptoms include oedema in the area, trismus as well as otalgia. The lesion tends to begin on one side of the face and eventually becomes bilateral.[13] The transmission of the paramyxovirus is by contact with the infected persons saliva.[13] Initial symptoms tend to be a headache and fever. Mumps is not fatal, however further complications can include swelling of the ovaries or the testes.[13] Diagnosis of mumps is confirmed through viral serology, management of the condition includes hydration and good oral hygiene of the patient[13] requiring excellent motivation. However, since the development of the mumps vaccine, given at the age of between 4–6 years, the incidence of this viral infection has greatly reduced. This vaccine has reduced the incidence by 99%.[13]

Fibrous reactions

editTuberculosis and syphilis can cause granuloma formation in the parotid glands.

Salivary stones

editSalivary stones mainly occur within the main confluence of the ducts and within the main parotid duct. The patient usually complains of intense pain when salivating and tends to avoid foods which produce this symptom. In addition, the parotid gland may become enlarged upon trying to eat. The pain can be reproduced in clinic by squirting lemon juice into the mouth. Surgery depends upon the site of the stone: if within the anterior aspect of the duct, a simple incision into the buccal mucosa with sphinterotomy[clarification needed] may allow removal; however, if situated more posteriorly[clarification needed] within the main duct, complete gland excision may be necessary.

Injury

editThe parotid salivary gland can also be pierced and the facial nerve temporarily traumatized when an inferior alveolar local anesthesia nerve block is incorrectly administered, causing transient facial paralysis.[4]

Cancer and tumours

editAbout 80% of tumors of the parotid gland are benign.[14] The most common of these include pleomorphic adenoma (70% of tumors,[14] of which 60% occur in females[14]) and Warthin tumor (i.e. adenolymphoma, which is more common in males than in females). Their importance is in relation to their anatomical position and tendency to grow over time. The tumorous growth can also change the consistency of the gland and cause facial pain on the involved side.[4]

Around 20% of parotid tumors are malignant, with the most common tumors being mucoepidermoid carcinoma and adenoid cystic carcinoma. Other malignant tumors of the parotid gland include acinic cell carcinoma, carcinoma expleomorphic adenoma, adenocarcinoma (arising from ductal epithelium of parotid gland), squamous cell carcinoma (arising from parenchyma of parotid gland), and undifferentiated carcinoma. Metastasis from other sites like phyllodes tumour of breast presenting as parotid swelling have also been described.[15] Critically, the relationship of the tumor to the branches of the facial nerve (CN VII) must be defined because resection may damage the nerves, resulting in paralysis of the muscles of facial expression.

Benign

editNeoplastic lesions of the parotid salivary gland can either be benign or malignant. Within the parotid gland, nearly 80% of tumours are benign.[17] Benign lesions tend to be painless, asymptomatic and slow-growing. The most common salivary gland neoplasms in children are hemangiomas, lymphatic malformations, and pleomorphic adenomas.[13] Diagnosis of benign lesions require a fine-needle-like aspiration biopsy.[13] With various benign lesions, most commonly the pleomorphic adenoma, there is a risk of developing malignancy over time.[13] As a result, these lesions are typically resected.

Pleomorphic adenoma is seen to be a common benign neoplasm of the salivary gland and has an overall incidence of 54–68%.[13] The Warthin tumour has a lower incidence of 6–10%; this tumour is associated with smoking and is more common in older men.[13] Benign lesions of the parotid gland have a significantly higher incidence than malignant lesions.

Malignant

editMalignant salivary gland lesions are rare. However, when a tumour extends to the submandibular, sublingual and the minor salivary glands, they tend to be malignant.[13] Distinguishing a malignant lesion from a benign one may be difficult as they both present as painless lesions.[13] A biopsy is crucial in aiding diagnosis. There are common signs that can highlight the presence of a malignant lesion. These include facial nerve weakness, rapid increase of the size of the lump as well as ulceration of the mucosa of the skin.[13]

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma is a common malignant tumour of the salivary glands and has a low incidence of 4–13%.[13] Adenoid cystic carcinoma is also a common malignant salivary gland lesion and has an incidence of 4–8%. This carcinoma tends to invade nerves and can re-occur post-treatment.[13]

Polycystic parotid disease

editA developmental polycystic disease of the salivary gland is seen to be extremely rare and is seen to be independent of recurrent parotitis.[18] The cause is thought to be a defect in the interactions between activin, follistatin and TGF-β, leading to a developmental disorder of glandular tissue.[18]

Surgery

editSurgical treatment of parotid gland tumors is sometimes difficult because of the anatomical relations of the facial nerve parotid lodge, as well as the increased potential for postoperative relapse. Thus, detection of early stages of a parotid tumor is extremely important in terms of postoperative prognosis.[14] Operative technique is laborious, because of relapses and incomplete previous treatment made in other border specialties.[14] Surgical techniques in parotid surgery have evolved in the last years with the use of neuromonitoring of the facial nerve and have become safer and less invasive.[19]

After surgical removal of the parotid gland (parotidectomy), the auriculotemporal nerve is liable to damage and upon recovery it fuses with sweat glands. This can cause sweating on the cheek on the side of the face of the affected gland. This condition is known as Frey's syndrome.[20]

Infections

editBacterial infections

editAcute bacterial parotitis

editCommonly caused by a retrograde bacterial infection as a result of illness, sepsis, trauma, surgery, reduced salivary flow due to medications, diabetes, malnutrition and dehydration. Classically symptoms of painful swelling in the parotid region when eating seen. Management is based upon antibacterials, rehydration combined with gentle massage to encourage salivary flow.[21]

Chronic bacterial parotitis

editA latent infection despite clinical resolution of the disease resulting in impaired function. Histologically glandular duct dilation, abscess formation and atrophy may be seen. Parotid secretions are viscous. Disease course shows pain and swelling, waxing and waning. Radiographic screening should be undertaken to rule out sialolith. Management with palliative care with parotidectomy as a last resort.[21]

Viral infections

editMumps

editAcute non-suppurative disease that often occurs in epidemics. Prevented by MMR vaccine. Caused by paramyxovirus that is transmitted by infected saliva and urine. A prodromal period of 24–28 hours is experienced, followed by rapid and painful swelling of the parotid gland. Treatment is supportive (bedrest, hydration) as spontaneous resolution occurs within 5–10 days.[21]

HIV / AIDS

editDiffuse gland enlargement is seen, and may affect patients throughout all stages of the infection. Lymphoepithelial cysts[22] seen via imaging help aid diagnosis. Pathogenic process occurs due to circulating CD8 lymphocytes within the salivary gland. Medical management via use of antiretrovirals, excellent oral hygiene measures and sialogogues.[21]

Autoimmune related

editSystemic lupus erythematosus

editMost commonly seen in fourth and fifth decades in women, and can affect any salivary gland. Presentation is a slowly enlarging gland, with diagnosis made by identification of the underlying systemic disorder and measurements of salivary chemical levels. Sodium and chloride ion levels will be elevated two or three times normal levels. Treatment is by addressing the underlying systemic condition.[21]

Sarcoidosis

editSarcoidosis is a chronic systemic disease characterised by the production of non-caseating granulomas of unknown aetiology. It can affect any organ of the body, depressing cellular immunity and enhancing humoral immunity.

Salivary gland involvement primarily involves both parotid glands, causing enlargement and swelling. Salivary gland biopsy with histopathologic examination is needed to make the distinction between whether Sjoren's syndrome or sarcoidosis is the cause of this.[21]

Sjogren's syndrome

editSalivary gland enlargement occurs in up to 30% of patients with Sjogren's syndrome, with the parotid gland being most often enlarged, and bilateral parotid gland enlargement seen in 25–60% of patients. However, the parotid glands have a longer-lasting secretory capacity in Sjogren's syndrome patient and therefore are the last glands to manifest hyposalivation in the disease. Histopathology shows clustering of lymphocytic infiltrates and epimyoepithelial islands.[21]

Mycobacterial infection

editThe most common head and neck manifestation of tuberculosis mycobacterial disease is infection of cervical lymph nodes. The infection is thought to originate in the tonsils or gingiva, ascending to the parotid gland. Two clinical forms; acute and chronic lesions. Acute lesions have diffuse glandular edema, easily confused with acute sialdentitis or abscess. The chronic lesions occur as slow growing masses mimicking tumors.[21]

Examination of the salivary gland

editHistory and examination

editA patient with parotid swelling may complain of swelling, pain, xerostomia, bad taste and sometimes sialorrhoea.[23]

The most common presenting symptom of neoplasms (both benign and malignant) is an asymptomatic swelling. Pain is more common in patients with parotid cancer (10–29% feel pain) than those with benign neoplasms (only 2.5–4%),[23] but pain itself it not diagnostic of malignancy.

Episodic swelling of major salivary glands accompanied by pain and related to salivary stimuli suggests duct obstruction.

Also need to assess the facial nerve. The facial nerve passes through the parotid so may be affected if there is a change in the parotid gland. Facial nerve paralysis in a previously untreated patient usually indicates that a tumour is malignant.[23]

Physical examination

editThe superficial location of the salivary glands allows palpation and visual inspection. The inspection must be systematic, both intraorally and extraorally, so no area is missed.

For extraoral examination the patients head should be inclined forwards in order to maximally expose the parotid and submandibular glands. A normal parotid gland is barely palpable and a normal sublingual gland is not palpable.[23]

Intra-oral examination should include observations for asymmetry, discolouration, pulsation and obstructions in the duct orifices. Swelling of the deep lobe of the parotid gland may be seen intra-orally, and may also displace the tonsil. The minor salivary glands should be examined. The labial, buccal and posterior palatal mucosa should be dried with an air blower or tissue and pressed to assess the flow of saliva.[23]

Salivary testing

editSalivary stimulation

- This can be done by palpating the parotid gland, thus stimulating it. Assess to see whether there is saliva flowing from the parotid papilla.

- Sialograms can identify changes in salivary gland architecture and are useful in the evaluation of major gland swellings

- It involves the instillation of a radio-opaque fluid into the major gland ductal system. This outlines the major and minor ductal systems, and also gives an outline of the glandular tissue

- For example, sialadenitis creates an appearance known as “pruning of the tree”[24] on a sialogram, where there are less branches visible from the duct system. Also, a space occupying lesion that occurs within or adjacent to a salivary gland can displace the normal anatomy of the gland. This may create an appearance known as “ball in hand”[24] on a sialogram, where the ducts are curved around the mass of the lesion.

Sialochemistry

- The composition of saliva changes in disease states, and analysis of saliva for enzymes, electrolytes, hormones, drugs and immunisation status can be performed.

Radioisotope scintigraphy

- Gives an objective measure of isotope uptake and excretion using a gamma scintillation camera. After about 20 minutes, a salivary stimulant will be given to promote salivary flow through the gland.[25] They are used to assess patients with persistent symptoms of dry mouth and also to evaluate salivary gland swelling due to infection, inflammation or obstruction.[26]

Further tests

edit- Imagining techniques

- Ultrasounds, CT Scans or MRIs can aid with disease localisation

- Sialoendoscopy

- A camera is inserted into the duct of a salivary gland to assess blockages

- Biopsy

- This can be done by fine needle aspiration biopsy, which provides an opportunity to obtain information about the histology of a salivary tumour prior to initiation of treatment.[23]

Additional images

edit-

Parotid gland (incorrect muscle name)

-

Mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve (fifth cranial nerve)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Submandibular Gland: Location, Function and Complications".

- ^ a b Ibrahim, Dalia. "Accessory parotid gland | Radiology Reference Article". Radiopaedia.

- ^ a b Jacobs S (2008). "Chapter 7: Head and Neck". Human Anatomy. Elsevier. p. 193. doi:10.1016/B978-0-443-10373-5.50010-5. ISBN 978-0-443-10373-5.

- ^ a b c d Fehrenbach MJ, Herring SW (2012). Illustrated anatomy of the head and neck (4th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4377-2419-6.

- ^ McGurk, Simon (2013-09-11). "Moore: Clinically Oriented Anatomy – Eighth international edition Moore: Clinically Oriented Anatomy – Eighth international edition". Nursing Standard. 28 (2): 1939. doi:10.7748/ns2013.09.28.2.28.s36. ISSN 0029-6570.

- ^ Sinnatamby, Chummy S. (2011). Last's Anatomy (12th ed.). Elsevier Australia. ISBN 978-0-7295-3752-0.

- ^ Spratt JD, Abrahams PH, Boon JM, Hutchings RT (2008). McMinn's Clinical Atlas of Human Anatomy (6th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Mosby. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-8089-2318-3.

- ^ a b Nanci A (2013). Ten Cate's Oral Histology: Development, Structure, and Function (8th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-07846-7.

- ^ "The Parotid Gland". TeachMeAntatomy.info. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Bath-Balogh M, Fehrenbach MJ (2011). Illustrated Dental Embryology, Histology, and Anatomy (3rd ed.). Elsevier. p. 135. ISBN 978-1-4377-1730-3.

- ^ Arhakis A, Karagiannis V, Kalfas S (2013). "Salivary alpha-amylase activity and salivary flow rate in young adults". The Open Dentistry Journal. 7: 7–15. doi:10.2174/1874210601307010007. PMC 3601341. PMID 23524385.

- ^ Moore P (2003). The Developing Human (7th ed.). Saunders. pp. 203, 220. ISBN 978-0-8089-2265-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wilson KF, Meier JD, Ward PD (June 2014). "Salivary gland disorders". American Family Physician. 89 (11): 882–88. PMID 25077394.

- ^ a b c d e Bucur A, Dincă O, Niță T, Totan C, Vlădan C (Mar 2011). "Parotid tumors: our experience". Rev. Chir. Oro-maxilo-fac. Implantol. 2 (1): 7–9. ISSN 2069-3850. Archived from the original on January 13, 2013.(webpage has a translation button)

- ^ Sivaram P, Rahul M, Jayan C, Sulfekar MS (2015). "Metastatic Malignant Phyllodes Tumour: An Interesting Presentation as a Parotid Swelling". New Indian Journal of Surgery. 6 (3): 75–77. doi:10.21088/nijs.0976.4747.6315.2. ISSN 0976-4747.

- ^ Steve C Lee (22 December 2022). "Salivary Gland Neoplasms". Medscape. Updated: Jan 13, 2021

- Image by Mikael Häggström, MD - ^ Mehanna H, McQueen A, Robinson M, Paleri V (October 2012). "Salivary gland swellings". BMJ. 345: e6794. doi:10.1136/bmj.e6794. PMID 23092898. S2CID 373247.

- ^ a b Iro H, Zenk J (2014-12-01). "Salivary gland diseases in children". GMS Current Topics in Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. 13: Doc06. doi:10.3205/cto000109. PMC 4273167. PMID 25587366.

- ^ Psychogios, Georgios; Bohr, Christopher; Constantinidis, Jannis; Canis, Martin; Vander Poorten, Vincent; Plzak, Jan; Knopf, Andreas; Betz, Christian; Guntinas-Lichius, Orlando; Zenk, Johannes (2020-08-04). "Review of surgical techniques and guide for decision making in the treatment of benign parotid tumors". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 278 (1): 15–29. doi:10.1007/s00405-020-06250-x. ISSN 0937-4477. PMID 32749609. S2CID 220965351.

- ^ Office of Rare Diseases Research (2011). "Frey's syndrome". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Carlson ER, Ord RA (2015). Salivary Gland Pathology: Diagnosis and Management (Second ed.). Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley/Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-93375-6. OCLC 904400135.

- ^ Sujatha D, Babitha K, Prasad RS, Pai A (November 2013). "Parotid lymphoepithelial cysts in human immunodeficiency virus: a review". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 127 (11): 1046–49. doi:10.1017/S0022215113002417. PMID 24169222. S2CID 33861207.

- ^ a b c d e f Anniko M, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Bonkowsky V, Bradley P, Iurato S, eds. (2010). Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-42940-1.

- ^ a b Schlieve T, Kolokythas A, Miloro M (2015). "Chapter 14: Salary Gland Infections". In Hupp JR, Ferneini EM (eds.). Head, Neck and Orofacial Infections: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-323-28946-7.

- ^ Kumar BS, Sathasivasubramanian SP (January 2012). "The role of salivary gland scintigraphy in detection of salivary gland dysfunction in type 2 diabetic patients". Indian Journal of Nuclear Medicine. 27 (1): 16–19. doi:10.4103/0972-3919.108832. PMC 3628255. PMID 23599592.

- ^ "Salivary gland function scan". Johns Hopkins Sjogrens Center. Retrieved 2018-03-25.

External links

edit- Illustration at yoursurgery.com

- lesson4 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- Salivary gland infections from Medline Plus

- Salivary gland cancer from American Cancer Society