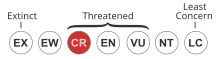

The giant pangasius, paroon shark, pangasid-catfish[1] or Chao Phraya giant catfish (Pangasius sanitwongsei) is a species of freshwater fish in the shark catfish family (Pangasiidae) of order Siluriformes, found in the Chao Phraya and Mekong basins in Indochina. Its populations have declined drastically, mainly due to overfishing, and it is now considered Critically Endangered.[1]

| Giant pangasius | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Berlin Aquarium, Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Siluriformes |

| Family: | Pangasiidae |

| Genus: | Pangasius |

| Species: | P. sanitwongsei

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pangasius sanitwongsei Smith, 1931

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

Etymology

editThe specific name sanitwongsei was chosen by H.M. Smith to honor M. R. Suwaphan Sanitwong (Thai: ม.ร.ว.สุวพรรณ สนิทวงศ์) for his support of fisheries in Thailand.[2]

Habitat

editThe species is native to the Mekong and Chao Phraya rivers that run through China, Cambodia, Thailand, Viet Nam, and the Lao People's Democratic Republic. It has been introduced to central Anatolia,[3] South Africa,[4] and Malaysia.[5]

The Pangasius sanitwongsei is tolerant of poor quality water,[4] mainly in brackish waters, and prefers to live in the bottom of deep depressions in freshwater rivers.[6][failed verification] The fish live in rivers but are experiencing endangerment due to dams being built, causing the fish to be trapped and unable to migrate.[7] There are currently two sub-populations of Paroon Shark separated by the Khone Falls which they do not migrate over.[8]

Physical characteristics

editThe giant pangasius is a ray-finned fish part of the family Pangasiidae commonly known as shark catfishes. They are recognized for having both dorsal and ventral long fins, which help stabilize the fish and keep it upright.[9] This adds to their bilateral symmetry corresponding to their developed swimming ability. Its skin is pigmented with dusky melanophores that help with camouflage in bottom waters. It has a wide, flat, whiskerless head. Its body is compressed and elongate, with a depressed head.[10] It has a continuous and uninterrupted single vomero-palatine teeth patch which is curved.[11] The anal fin has 26 rays and the pectoral spine is similar in size to the dorsal spine and also shows serrations.[10] It has a silver, curved underside and a dark brown back. Its dorsal, pectoral and pelvic fins are dark gray and the first soft ray is extended into a filament. Its dorsal, adipose, pectoral, and caudal fins are a dark grey to black coloring, with its anal fin and pelvic fins a white to grey coloring.[4] Full-grown adults can reach 300 centimetres (9.8 ft) SL in length and weigh up to 300 kg (660 lb).[12] More commonly the fish's length is around 2 meters.[6]

Development

editLittle is known of the reproduction of P. sanitwongsei, but the time of spawning happens in the months of April and May.[6] It is predicted that spawning happens in the rivers where they are found; they are not believed to be migrating from outside the river when getting ready to spawn.[13]

Eggs and sperm are usually released in a muddier area to prevent eggs from sticking to each other.[14] The number of eggs per each spawning is around 600 (with a diameter of 2–2.5mm) and the brood shows low genetic variation.[6] There is no parental care after spawning.[15]

Behavior

editThe giant pangasius is a benthopelagic and migratory species. Juveniles and adults feed on crustaceans and fishes. These fish typically spawn just prior to the monsoon season.[12] It is believed that the P. sanitwongsei prey on shrimp, crabs, and fish and hideout in deep areas in rivers.[6] The P. sanitwongsei have a seasonal migration but the fish does not leave the river during its migration, it only stays within the river during the seasonal migration.[16]

Food habits

editThe P. sanitwongsei is a carnivorous fish, whose prey consist of shrimp, crabs, and fish.[6] Since the fish lives on the bottom, it is also known to feed on larger animals' carcasses.[4] Due to it being both an apex predator and a bottom-dwelling fish, it limits the populations of smaller fish as many catfish species.

Longevity

editThis fish's lifespan isn't known, but it is known that it grows fast[4] and usually the trend is when it grows fast, it dies quickly.[citation needed] The possible reasoning for this could be the fact that there is over-fishing of the species.[3]

Ecosystem roles

editThe P. sanitwongsei's role in the ecosystem is the top predator, therefore inflicts top down control on the population. Top predators aid in the limitation of smaller organisms and in this case they prey on smaller fish keeping the smaller fish in check. Without these carnivorous predators, the smaller fish could overpopulate and throw the food chain into imbalance.[17] Due to overharvesting, the native fish population may increase since the P. sanitwongsei population is declining.[18]

Economic importance

editThis fish is important to many locals that reside in the regions where the rivers run through as this is an important food source. Many fishing villages rely on the organisms that reside in the river to provide food for their family as well as a source of income as they can sell them at markets. Due to this fish's large known range, it can show us migratory pathways and spawning habits and areas that should be protected, and other areas that can be harvested.[6] This species of fish is also important to fisheries as it can grow to large sizes, even in captivity, and build an economy that relies heavily on fish and other water species. This was a significant reason why it was introduced to rivers in South Africa.[4]

These fishes are also valuable asset in the pet trade. They are considered exotic organisms as they are not commonly found in aquariums and are not domesticated. This introduced species in South African rivers can also be a case of release from aquariums once they could no longer be contained due to their high energy need and large size.[4]

Relationship to humans

editFishing of this species used to be accompanied by religious ceremonies and rites. It is often mentioned in textbooks, news media, and popular press. This fish is a popular food fish and marketed fresh.[12] They were introduced to Malaysia for both food and as an ornamental fish.

These fish sometimes appear in the aquarium fish hobby. Most specimens do not reach their full size without an extremely large aquarium or pond. There is even a "balloon" form of this fish where the fish has an unusually short and stocky body.[19]

In addition to fishing for religious purposes, they are also hunted for sport as they are the largest of their kind. They are considered trophy fish and are hunted for prestige and fame. The downside is that these individuals are the most fecund and mature which leads to a decrease in population if too many are harvested at one time. This further makes them a topic of conservation as they play key roles in their ecosystem.[20]

Threats & Conservation Solutions

editThis fish is highly protected and has a high conservation value and is banned from being fished through all seasons.[21] The fish is being threatened by overharvesting, damming of rivers, and pollution. Their population continues to decline as there are not many legislations and enforcement toward this species. A common threat to these large organisms is dams and segmentation of the Mekong River. The Paroon shark travels upstream to spawn and resides downstream. The construction of dams leads to segmentation of the natural habitat.[22] Even though the bodies of water are interconnected these fish are not capable of swimming through walls to get to their natural breeding sites.

Aside from being threatened by anthropogenic causes, the Giant Pangasius is considered an umbrella species in conservation. Protecting this species would provide protection for species that inhabit the same region. With this tactic, a whole ecosystem can be preserved. Due to this area being an area that is highly fished commercially and locally, certain regulations can be put in place to manage the size of the fish that can be caught allowing mature adults to reproduce with greater success. [23]

A known breeding practice, to try and help the population, is being practiced by the Thai government.[6] A halt on harvesting has been recommended until the P. sanitwongsei's population can rise to a safe level.[6] Even though these fish are grown in a safe fishery, this can reduce the genetic diversity between them making them more susceptible to disease as well as environmental stress.

Regulations and Restrictions

editTo control the amount of overharvesting (via fishing) that occurs certain size and catch limits can be put in place. In 1989, the Paroon shark was listed as a class II protected species by the government of Yunnan, China.[8] The issue is that the habitat of this species lies in multiple countries' domains including Cambodia, Lao People's Democratic Republic, Thailand, and Viet Nam. Restrictions in parts of the river that reside in China's territory, leave the other parts to be unprotected.

There are some groups in the Asian continent who have been trying to protect and conserve the wildlife in these regions including the Asian Species Action Partnership (ASAP), Species Survival Commission (SSC), World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).[24]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Jenkins, A.; Kullander, F.F. & Tan, H.H. (2009). "Pangasius sanitwongsei". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2009. IUCN: e.T15945A5324983. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009-2.RLTS.T15945A5324983.en.

- ^ ลักษณะทั่วไปของปลาเทพา (in Thai). Department of Fisheries of Thailand. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ^ a b Baran Yoğurtçuoğlu; Fitnat Ekmekçi (30 September 2018). "First record of the giant pangasius, Pangasius sanitwongsei (Actinopterygii: Siluriformes: Pangasiidae), from central Anatolia, Turkey". Acta Ichthyologica et Piscatoria. 48 (3): 241–244. doi:10.3750/AIEP/02407. ISSN 0137-1592. Wikidata Q124499874.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tuuli Mäkinen; Olaf L.F. Weyl; Kerry-Ann van der Walt; Ernst R. Swartz (October 2013). "First Record of an Introduction of the Giant Pangasius, Pangasius sanitwongsei Smith 1931, Into an African River". African Zoology. 48 (2): 388–391. doi:10.3377/004.048.0209. ISSN 1562-7020. S2CID 219293718. Wikidata Q56939142.

- ^ "Invasive fish species reared at abandoned mines moving into major rivers". Nst.com.my. 7 March 2021. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Zeb Hogan; Uthairat Na-Nakorn; Heng Kong (25 October 2008). "Threatened fishes of the world: Pangasius sanitwongsei Smith 1931 (Siluriformes: Pangasiidae)". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 84 (3): 305–306. doi:10.1007/S10641-008-9419-6. ISSN 0378-1909. Wikidata Q124499876.

- ^ Richard Stone (1 March 2010). "Ecology. Severe drought puts spotlight on Chinese dams". Science. 327 (5971): 1311. doi:10.1126/SCIENCE.327.5971.1311. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 20223955. Wikidata Q51176006.

- ^ a b "Giant Pangasius". Asian Species Action Partnership. 30 October 2015. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- ^ "Giant Pangasius - Encyclopedia of Life". www.eol.org. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ^ a b Hugh M. Smith (1931). "Descriptions of new genera and species of Siamese fishes" (PDF). Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 79 (2873): 1–48. doi:10.5479/SI.00963801.79-2873.1. ISSN 0096-3801. Wikidata Q29011707.

- ^ Arvind K. Dwivedi; Braj Kishor Gupta; Rajeev K. Singh; Vindhya Mohindra; Suresh Chandra; Suresh Easawarn; Joykrushna Jena; Kuldeep K. Lal (24 April 2017). "Cryptic diversity in the Indian clade of the catfish family Pangasiidae resolved by the description of a new species". Hydrobiologia. 797 (1): 351–370. doi:10.1007/S10750-017-3198-Z. ISSN 0018-8158. Wikidata Q60357243.

- ^ a b c Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Pangasius sanitwongsei". FishBase. February 2012 version.

- ^ Samorn Kwantong; Amrit N Bart (August 2003). "Effect of cryoprotectants, extenders and freezing rates on the fertilization rate of frozen striped catfish,<i>Pangasius hypophthalmus</i>(Sauvage), sperm". Aquaculture Research. 34 (10): 887–893. doi:10.1046/J.1365-2109.2003.00897.X. ISSN 1355-557X. Wikidata Q124499886.

- ^ Chanthasoo, Manat; Wiwatcharakoset, Suraphong; Lisanga, Sanga (1990). "Breeding of Chao Phaya giant catfish (Pangasius Sanitwongsei)". Warasan Kan Pramong. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Kednapat Sriphairoj; Uthairat Na-Nakorn; Sirawut Klinbunga (February 2018). "Species identification of non-hybrid and hybrid Pangasiid catfish using polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism". Agriculture and Natural Resources. 52 (1): 99–105. doi:10.1016/J.ANRES.2018.05.014. ISSN 2452-316X. Wikidata Q124499889.

- ^ Na-Nakorn, Uthairat; Sukmanomon, Srijanya; Poompuang, Supawadee; Saelim, Panya; Taniguchi, Nobuhiko; Nakajima, Masanishi. "Genetic diversity of the vulnerable Pangasius sanitwongsei using microsatellite DNA and 16S rRNA". AGRIS. Kasetsart University Fisheries Research Bulletin. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ CS Sherman; MR Heupel; SK Moore; A Chin; CA Simpfendorfer (27 March 2020). "When sharks are away, rays will play: effects of top predator removal in coral reef ecosystems". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 641: 145–157. doi:10.3354/MEPS13307. ISSN 0171-8630. Wikidata Q113392421.

- ^ Fengzhi He; Christiane Zarfl; Vanessa Bremerich; Alex Henshaw; William Darwall; Klement Tockner; Sonja C. Jähnig (21 February 2017). "Disappearing giants: a review of threats to freshwater megafauna". WIREs. Water. 4 (3): e1208. doi:10.1002/WAT2.1208. ISSN 2049-1948. Wikidata Q56703352.

- ^ ""Short body" อีกหนึ่งสีสันของปลาน้ำจืดไทย" (PDF). Fisheries.go.th. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ D.S. Shiffman; A.J. Gallagher; J. Wester; C.C. Macdonald; A.D. Thaler; S.J. Cooke; N. Hammerschlag (December 2014). "Trophy fishing for species threatened with extinction: A way forward building on a history of conservation". Marine Policy. 50: 318–322. doi:10.1016/J.MARPOL.2014.07.001. ISSN 0308-597X. Wikidata Q114663549.

- ^ U. Na‐Nakorn; S. Sukmanomon; M. Nakajima; N. Taniguchi; W. Kamonrat; S. Poompuang; T. T. T. Nguyen (6 September 2006). "MtDNA diversity of the critically endangered Mekong giant catfish (<i>Pangasianodon gigas</i> Chevey, 1913) and closely related species: implications for conservation". Animal Conservation. 9 (4): 483–494. doi:10.1111/J.1469-1795.2006.00064.X. ISSN 1367-9430. Wikidata Q124499899.

- ^ "Pangasius sanitwongsei (Paroon Shark) — Seriously Fish". Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- ^ JEAN‐MICHEL ROBERGE; PER ANGELSTAM (30 January 2004). "Usefulness of the Umbrella Species Concept as a Conservation Tool". Conservation Biology. 18 (1): 76–85. doi:10.1111/J.1523-1739.2004.00450.X. ISSN 0888-8892. Wikidata Q124499898.

- ^ "Partner zone". Asian Species Action Partnership. 25 October 2021. Retrieved 2023-04-13.