This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

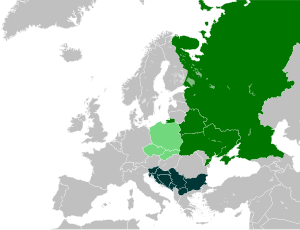

Pan-Slavism, a movement that took shape in the mid-19th century, is the political ideology concerned with promoting integrity and unity for the Slavic people. Its main impact occurred in the Balkans, where non-Slavic empires had ruled the South Slavs for centuries. These were mainly the Byzantine Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Venice.

Origins

editExtensive pan-Slavism began much like Pan-Germanism: both of these movements flourished from the sense of unity and nationalism experienced within ethnic groups after the French Revolution and the consequent Napoleonic Wars against traditional European monarchies. As in other Romantic nationalist movements, Slavic intellectuals and scholars in the developing fields of history, philology, and folklore actively encouraged Slavs' interest in their shared identity and ancestry. Pan-Slavism co-existed with the Southern Slavic drive towards independence.

Commonly used symbols of the Pan-Slavic movement were the Pan-Slavic colours (blue, white and red) and the Pan-Slavic anthem, Hey, Slavs.

The first pan-Slavists were the 16th-century Croatian writer Vinko Pribojević, the Dalmatian Aleksandar Komulović (1548–1608), the Croat Bartol Kašić (1575–1650), the Ragusan Ivan Gundulić (1589–1638) and the Croatian Catholic missionary Juraj Križanić (c. 1618 – 1683).[1][2][3] Scholars such as Tomasz Kamusella have attributed early manifestations of Pan-Slavic thought within the Habsburg monarchy to the Slovaks Adam Franz Kollár (1718–1783) and Pavel Jozef Šafárik (1795–1861).[4][5][need quotation to verify] The Pan-Slavism movement grew rapidly following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. In the aftermath of the wars, the leaders of Europe sought to restore the pre-war status quo. At the Congress of Vienna of 1814–1815, Austria's representative, Prince von Metternich, detected a threat to this status quo in the Austrian Empire through nationalists' demands for independence from the empire.[6] While Vienna's subjects included numerous ethnic groups (such as Germans, Italians, Romanians, Hungarians, etc.), the Slav proportion of the population (Poles, Ruthenians, Ukrainians, Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Serbs, Bosniaks and Croats) together formed a substantial—if not the largest—ethnic grouping.

First Pan-Slav Congress, Prague, 1848

editThe First Pan-Slav congress was held in Prague, Bohemia, in June 1848, during the revolutionary movement of 1848. The Czechs had refused to send representatives to the Frankfurt Assembly feeling that Slavs had a distinct interest from the Germans. The Austroslav, František Palacký, presided over the event. Most of the delegates were Czech and Slovak. Palacký called for the co-operation of the Habsburgs and had also endorsed the Habsburg monarchy as the political formation most likely to protect the peoples of central Europe. When the Germans asked him to declare himself in favour of their desire for national unity, he replied that he would not as this would weaken the Habsburg state: “Truly, if it were not that Austria had long existed, it would be necessary, in the interest of Europe, in the interest of humanity itself, to create it.”

The Pan-Slav congress met during the revolutionary turmoil of 1848. Young inhabitants of Prague had taken to the streets and in the confrontation, a stray bullet had killed the wife of Field Marshal Alfred I, Prince of Windisch-Grätz, the commander of the Austrian forces in Prague. Enraged, Windischgrätz seized the city, disbanded the congress, and established martial law throughout Bohemia.

Pan-Slavism in the Czech lands and Slovakia

editheritage" in 8 Slavic languages.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

The first Pan-Slavic convention was held in Prague on June 2 through 16, 1848.[8] The delegates at the Congress were specifically both anti-Austrian and anti-Russian. Still "the Right"—the moderately liberal wing of the Congress—under the leadership of František Palacký (1798–1876), a Czech historian and politician,[9] and Pavol Jozef Šafárik (1795–1861), a Slovak philologist, historian and archaeologist,[10] favored autonomy of the Slav lands within the framework of Austrian (Habsburg) monarchy.[11] In contrast "the Left"—the radical wing of the Congress—under the leadership of Karel Sabina (1813–1877), a Czech writer and journalist, Josef Václav Frič, a Czech nationalist, Karol Libelt (1817–1861), a Polish writer and politician, and others, pressed for a close alliance with the revolutionary-democratic movement going on in Germany and Hungary in 1848.[11]

A national rebirth in the Hungarian "Upper Land" (now Slovakia) awoke in a completely new light, both before the Slovak Uprising in 1848 and after. The driving force of this rebirth movement were Slovak writers and politicians who called themselves Štúrovci, the followers of Ľudovít Štúr. As the Slovak nobility was Magyarized and most Slovaks were merely farmers or priests, this movement failed to attract much attention. Nonetheless, the campaign was successful as brotherly cooperation between the Croats and the Slovaks brought its fruit throughout the war. Most of the battles between Slovaks and Hungarians however, did not turn out in favor for the Slovaks who were logistically supported by the Austrians, but not sufficiently. The shortage of manpower proved to be decisive as well.

During the war, the Slovak National Council brought its demands to the young Austrian Emperor, Franz Joseph I, who seemed to take a note of it and promised support for the Slovaks against the revolutionary radical Hungarians. However the moment the revolution was over, Slovak demands were forgotten. These demands included an autonomous land within the Austrian Empire called "Slovenský kraj" which would be eventually led by a Serbian prince. This act of ignorance from the Emperor convinced the Slovak and the Czech elite who proclaimed the concept of Austroslavism as dead.

Disgusted by the Emperor's policy, in 1849, Ľudovít Štúr, the person who codified the first largely used Slovak language, wrote a book he would name Slavdom and the World of the Future. This book served as a manifesto where he noted that Austroslavism was not the way to go anymore. He also wrote a sentence that often serves as a quote until this day: "Every nation has its time under God's sun, and the linden [a symbol of the Slavs] is blossoming, while the oak [a symbol of the Teutons] bloomed long ago."[12]

He expressed confidence in the Russian Empire however, as it was the only country of Slavs that was not dominated by anybody else, yet it was one of the most powerful nations in the world. He often symbolized Slavs as being a tree, with "minor" Slavic nations being branches while the trunk of the tree was Russian. His Pan-Slavic views were unleashed in this book, where he stated that the land of Slovaks should be annexed by the Tsar's empire and that eventually, the population could be not only Russified, but also converted into the rite of Orthodoxy, religion originally spread by Cyril and Methodius during the times of Great Moravia, which served as an opposition to the Catholic missionaries from the Franks. After the Hungarian invasion of Pannonia, Hungarians converted into Catholicism, which effectively influenced the Slavs living in Pannonia and in the land south of the Lechs.

However, the Russian Empire often claimed Pan-Slavism as a justification for its aggressive moves in the Balkan Peninsula of Europe against the Ottoman Empire, which conquered and held the land of Slavs for centuries. This eventually led to the Balkan campaign of the Russian Empire, which resulted in the entire Balkan being liberated from the Ottoman Empire, with the help and the initiative of the Russian Empire.[13] Pan-Slavism has some supporters among Czech and Slovak politicians, especially among the nationalistic and far-right ones, such as People's Party – Our Slovakia.

During World War I, captured Slavic soldiers were asked to fight against "oppression in the Austrian Empire". Consequently, some did. (see Czechoslovak Legions)

The creation of an independent Czechoslovakia made the old ideals of Pan-Slavism anachronistic. Relations with other Slavic states varied, sometimes being so tense it escalated into an armed conflict, such as with the Second Polish Republic where border clashes over Silesia resulted in a short hostile conflict, the Polish–Czechoslovak War. Even tensions between Czechs and Slovaks had appeared before and during World War II.

Pan-Slavism among South Slavs

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2017) |

Pan-Slavism in the south, largely advocated by Serbs, would often turn to Russia for support.[14] The Southern Slavic movement advocated the independence of the Slavic peoples in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Most Serbian intellectuals sought to unite all of the Southern, Balkan Slavs, whether Catholic (Croats, Slovenes), Muslim (Bosniaks, Pomaks), or Orthodox (Serbs, Macedonians, Bulgarians) as a "Southern-Slavic nation of three faiths".

Austria feared that Pan-Slavists would endanger the empire. In Austria-Hungary Southern Slavs were distributed among several entities: Slovenes in the Austrian part (Carniola, Styria, Carinthia, Gorizia and Gradisca, Trieste, Istria), Croats and Serbs in the Hungarian part within the autonomous Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia and in the Austrian part within the autonomous Kingdom of Dalmatia, and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, under direct control from Vienna. Owing to a different position within Austria-Hungary, several different goals were prominent among the Southern Slavs of Austria-Hungary. A strong alternative to Pan-Slavism was Austroslavism,[15] especially among the Croats and Slovenes. Because the Serbs were dispersed among several regions, and the fact that they had ties to the independent nation state of Kingdom of Serbia, they were among the strongest supporters of independence of South-Slavs from Austria-Hungary and uniting into a common state under Serbian monarchy.

When in 1863 the Association of Serbian Philology commemorated the death of Cyril a thousand years earlier, its president Dimitrije Matić talked of the creation of an "ethnically pure" Slavonic people, "With God’s help, there should be a whole Slavonic people with purely Slavonic faces and of purely Slavonic character."[16]

After World War I the creation of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, under Serbian royalty of the Karađorđević dynasty, united most Southern Slavic-speaking nations regardless of religion and cultural background. The only ones they did not unite with were the Bulgarians. Still, in the years after the Second World War, there were proposals to incorporate Bulgaria into a Greater Yugoslavia thus uniting all south Slavic-speaking nations into one state.[17] The idea was abandoned after the split between Josip Broz Tito and Joseph Stalin in 1948. This led to some bitter sentiment between the people of Yugoslavia and Bulgaria in the aftermath.

At the end of the Second World War, the Partisans' mixed heritage leader Josip Broz Tito became Yugoslav president, and the country become a socialist republic, with the motto of "Brotherhood and Unity" between its various Slavic peoples.

Pan-Slavism in Poland

editWith the exception of Russia, the Polish nation has the distinction among other Slavic peoples of having enjoyed independence as a part of various entities for several centuries prior to the advent of Pan-Slavism.

After 1795, Revolutionary and Napoleonic France had influenced many Poles who sought the reconstitution of their existing country—particularly since France was a mutual enemy of Austria, Prussia, and also Russia. Russia's Pan-Slavic rhetoric had alarmed the Poles. Pan-Slavism was not fully embraced among Poles after the early period. Poland did nevertheless express solidarity with those of its fellow Slavic nations that had suffered oppression and were seeking independence.

While Pan-Slavism as an ideology was inimical to Austro-Hungarian interests, Poles instead embraced the wide autonomy within the state and assumed a loyalist position towards the Habsburgs. Within the Austro-Hungarian polity, they were able to develop their national culture and preserve the Polish language, both of which were under threat in both German and Russian Empires. A Pan-Slavic federation was proposed, but on the condition that the Russian Empire would be excluded from such an entity. After Poland regained its independence (from Germany, Austria and Russia) in 1918, no internal faction considered Pan-Slavism as a serious alternative, viewing Pan-Slavism as Russification. During Poland's communist era, the USSR used Pan-Slavism as a propaganda tool to justify its control over the country. The issue of Pan-Slavism was not part of current mainstream politics and is widely seen as an ideology of Russian imperialism.

Pan-Slavism in Russia

editDuring the time of the Soviet Union, Bolshevik teachings viewed Pan-Slavism as a reactionary element associated to the Russian Empire.[18] As a result, Bolsheviks viewed it as contrary to their Marxist ideology. Pan-Slavists even faced persecution during the Stalinist repressions in the Soviet Union (see Slavists case). Nowadays, ultranationalist parties like the Russian National Unity party advocate for a Russian-dominated 'Slavic Union'.[citation needed]

Modern-day developments

editThe authentic idea of the unity of the Slavic people was all but gone after World War I when the maxim "Versailles and Trianon have put an end to all Slavisms".[19] During the Cold War, all Slavic peoples were in union under the dominance of the USSR, but pan-Slavism was rejected as reactionary to Communist ideals, and this unity was largely put to rest with the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, leading to the breakup of federal states such as Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia.[20][21] Varying relations between the Slavic countries exist nowadays; they range from mutual respect on equal footing and sympathy towards one another through traditional dislike and enmity, to indifference. No forms, other than culture and heritage oriented organizations, are currently considered forms of rapprochement among the countries with Slavic origins.[22] The political parties which include Pan-Slavism as part of their program usually live on the fringe of the political spectrum, or are part of controlled and systemic opposition in Belarus, Russia and occupied territories, as part of an irredentist pan-slavist campaign by Russia.[23][24]

A political concept of Euro-Slavism evolved from the idea that European integration will solve issues of Slavic peoples and promote peace, unity and cooperation on equal terms within the European Union.[25][26] The concept seeks to resist strong multicultural tendencies from Western Europe, the dominant position of Germany, opposes Slavophilia, and typically encourages democracy and democratic values. Many Euroslavists believe it is possible to unite Slavic communities without exclusion of Russia from the European cultural area,[27] but are also opposed to Russophilia and concepts of Slavs under Russian domination and irredentism.[25] It is considered a modern form of Austro-Slavist and Neo-Slavist movements.[28][29] Their origins date back to the middle of the 19th century, being first proposed by Czech liberal politician Karel Havlíček Borovský in 1846, when it was refined into a provisional political program by Czech politician František Palacký and completed by the first President of Czechoslovakia Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk in his work New Europe: Slavic Viewpoint.[30]

Contemporary views

editWhile Pan-Slavism remains popular in moderate and extremist political circles, its popularity subsided in the public. After the failure of Yugoslavism and Czechoslovakism, nationalism in Slavic nations now focus on self-definition and non-ethnic relations (like Hungary and Poland). The Russo-Ukrainian War had a divisive role,[31] and pro-Russian sentiment became less popular. Tensions also rose on the Ukrainian side, and for economic reasons Ukrainian grain exports had to be banned for a time in multiple Slavic countries such as Poland and Slovakia, after the protest of farmers in multiple European countries.[32][33]

Creation of pan-Slavic languages

editSimilarities of Slavic languages inspired many to create zonal auxiliary Pan-Slavic languages for all Slavic people to communicate with one another. Several such languages were constructed in the past, but many more were created in the Internet Age. The most prominent modern example is Interslavic.[34]

Popular culture

editPan-Slavic countries, organisations, and alliances appear in various works of fiction.

In the 2014 turn-based strategy 4X game Civilization: Beyond Earth there is a playable faction called the Slavic Federation – a science fiction vision of Eastern Europe and Western Asia, reformed into a powerful unified state with a focus on aerospace, technological research, and terrestrial engineering.[35][36] Its leader, a former cosmonaut named Vadim Kozlov voiced by Mateusz Pawluczuk, speaks a mixture of Russian and Ukrainian with a heavy Polish accent.[37][38] In the historical grand strategy games of Crusader Kings II and Europa Universalis IV, the player is able to unite Slavonic territories via political alliances and multi-ethnic kingdoms.[39] The real-time strategy games Ancestors Legacy and the HD edition of Age of Empires II feature fictionalised versions of the early Slavs that incorporate and fuse elements from different Slavic nations.[39]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ John M. Letiche and Basil Dmytryshyn: "Russian Statecraft: The Politika of Iurii Krizhanich", Oxford and New York, 1985

- ^ Ivo Banac: "The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins, History, Politics", Cornell University Press, 1988, pp. 71

- ^ The Eighteenth Century: A Current Bibliography. American Society for Eighteenth Century Studies. 1992. p. 162. ISBN 9780001610996.

... the work of some early "Panslavic" ideologues in the sixteenth (Pribojevic) and seventeenth (Gundulic, Komulovic, Kasic,...)

- ^

Kamusella, Tomasz (2008-12-16). "The Slovak Case: From Upper Hungary's Slavophone Populus to Slovak Nationalism and the Czechoslovak Nation". The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe (reprint ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 539. ISBN 9780230583474. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

Kollár's and Šafárik's vision appealed for cultural unity of all the Slavs and for political cooperation and eventual unity of the Slavic inhabitants of the Austrian Empire.

- ^ Robert John Weston Evans, Chapter "Nationality in East-Central Europe: Perception and Definition before 1848". Austria, Hungary, and the Habsburgs: Essays on Central Europe, c. 1683–1867. 2006.

- ^

Vick, Brian E. (2014). "Between Reaction and Reform". The Congress of Vienna: Power and Politics after Napoleon. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 275. ISBN 9780674745483. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

The willingness to work in part with national sentiments within the Habsburg framework [...] went to the top: to Stadion, but also to Metternich. Metternich's commitment could be seen in a small symbolic way in his Habsburg folk-dress costume theme ball, but also appeared in his plans for Austria's reacquired Italian and Polish provinces. Metternich did not favor a full federal remodelling of the Habsburg Empire, as some have suggested, but neither did he oppose concessions to a presumed national spirit as much as several critics of that interpretation have contended. [...] Metternich and the Austrians certainly believed that there was an Italian national spirit, one that they feared and opposed if it pointed to national independence and republicanism, and they did intend to combat it through a policy of 'parcelization,' that is, bolstering local identities as a means to damp the growth of national sentiment. [...] Metternich and Franz, for instance, hoped to appeal to 'the Lombard spirit' to counteract 'the so-called Italian spirit.'

- ^ Вилинбахов Г. В. Государственная геральдика в России: Теория и практика (in Russian)

- ^ See Note 134 on page 725 of the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 14 (International Publishers: New York, 1980).

- ^ See the biographical note on page 784 of the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 14.

- ^ See the biographical note at page 787 of the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 14

- ^ a b See Note 134 on page 725 of the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 14.

- ^ (Slovak: Každý národ má svoj čas pod Božím slnkom, a lipa kvitne až dub už dávno odkvitol.) Slovanstvo a svet budúcnosti. Bratislava 1993, s. 59.

- ^ Frederick Engels, "Germany and Pan-Slavism" contained in the Collected Works of Karl Marx and Frederick Engels: Volume 14, pp. 156-158.

- ^ Yavus, M. Hakan; Sluglett, Peter (2011). War and Diplomacy: The Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 and the Treaty of Berlin. Salt Lake City: University of Utah. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1607811503.

- ^ Magocsi, Robert; Pop, Ivan, eds. (2005), "Austro-Slavism", Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, p. 21

- ^ Association of Serbian Philology: Hiljadugodišnja 1863:4

- ^ Ramet, Sabrina P.; The three Yugoslavias: state-building and legitimation, 1918-2005; Indiana University Press, 2006 ISBN 0-253-34656-8

- ^ "Панславизм / Большая советская энциклопедия". www.gatchina3000.ru. Retrieved 2022-02-01.

- ^ Comparative Slavic Studies Volume 6, by Roman Jakobson

- ^ Ulam, Adam B. (1951). "The Background of the Soviet-Yugoslav Dispute". The Review of Politics. 13 (1): 39–63. doi:10.1017/S0034670500046878. JSTOR 1404636. S2CID 146474329. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "Former Yugoslavia 101: The Balkans Breakup". NPR. 18 February 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ Guins, George C. (1948). "The Degeneration of 'Pan-Slavism'". The American Journal of Economics and Sociology. 8 (1): 50–59. doi:10.1111/j.1536-7150.1948.tb00729.x. JSTOR 3483821. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ Levine, Louis (1914). "Pan-Slavism and European Politics" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly. 29 (4): 664–686. doi:10.2307/2142012. JSTOR 2142012. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- ^ "In other words, the Pan-Slavic resentment is not strange to the Russian Eurasianists, however, this is prevailingly limited to the post-Soviet space. Therein lies the difference between the Eurasians and the Russian radical nationalists in their contemporary attitude to Pan-Slavism. Radical nationalists are the only ones who follow up with the tradition and ideational message of the Central- and South-European Pan-Slavism of the tsarist Russia. Pan-Slavism serves as their tool for demonstrating decisive anti-Western attitudes and as an "historical" folklore employed in domestic-political battles, which sound so sweet to the Russian ear. The ideas of Pan-Slavism only find some echo with the part of some Serbian and partly Slovak nationalists" Alexander Duleba, "From Domination to Partnership - The perspectives of Russian-Central-East European Relations", Final Report to the NATO Research Fellowship Program, 1996-1998 [1]

- ^ a b Wagner, Lukas (2009), The EU's Russian Roulette (PDF), Tampere: University of Tampere, pp. 74–78, 85–90, retrieved 19 March 2017

- ^ Morávek, Štefan (2007). Patriotizmus a šovinizmus (PDF) (in Slovak). Bratislava: Government Office of the Slovak Republic. p. 97. ISBN 978-80-88707-99-8. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Lukeš, Igor (1996). Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-19-510266-5.

- ^ Magcosi, Robert; Pop, Ivan, eds. (2002), "Austro-Slavism", Encyclopedia of Rusyn History and Culture, Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 21, ISBN 0-8020-3566-3

- ^ Mikulášek, Alexej (2014). "Ke koexistenci slovanských a židovských kultur" (in Czech). Union of Czech Writers. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Masaryk, Tomáš G. (2016). Nová Evropa: stanovisko slovanské (in Czech) (5 ed.). Prague: Ústav T.G. Masaryka. ISBN 978-80-86142-55-5.

- ^ "Russia's Invasion of Ukraine Is Just the Latest Expression of Pan-Slavic Authoritarianism | Mises Institute". mises.org. 2022-04-08. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ "Poland, Hungary, Slovakia impose own Ukraine grain bans as EU measure expires". POLITICO. 2023-09-16. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ "Farmers' protests: EU to cap some Ukrainian tariff-free imports". 2024-03-20. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ Katsikas, Sokratis K.; Zorkadis, Vasilios (2017). "4. The Interslavic Experiment". E-Democracy – Privacy-Preserving, Secure, Intelligent E-Government Services. Athens, Greece: Springer. p. 21. ISBN 978-3319711171.

- ^ Hajdasz, Alex (2016-11-13). "Best Sponsors in Beyond Earth & Rising Tide". celjaded.com. CelJaded. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ "Slavic Federation". ign.com. IGN. 2014-10-31. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

- ^ "Civilization: Beyond Earth (Video Game 2014) - Mateusz Pawluczuk as Vadim Petrovich Kozlov". imdb.com. IMDb. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ Goninon, Mark (2014-11-11). "Member Nations of Sponsor Factions in Civilization: Beyond Earth". choicestgames.com. Choicest Games. Retrieved 2023-03-26.

- ^ a b "Historical Eastern Europe in video games". youtube.com. Bamul Gaming. 2017-03-06. Retrieved 2023-03-25.

Further reading

edit- Kohn, Hans. Nationalism: Its meaning and history (van Nostrand, 1955).

- Kohn, Hans (1961). "The Impact of Pan-Slavism on Central Europe". The Review of Politics. 23 (3): 323–333. doi:10.1017/s0034670500008767. JSTOR 1405438. S2CID 145066436.

- Petrovich B.M. The Emergence of Russian Panslavism, 1856-1870 (Columbia University Press, 1956)

- Kostya S. Pan-Slavism (Danubian Press, 1981)

- Golub I., Bracewell C. The Slavic Idea of Juraj Krizanic, Harvard Ukrainian Studies 3-4 (1986).

- Tobolka Z. Der Panslavismus, Zeitschrift fur Politik, 6 (1913)

- Gasor A., Karl L., Troebst S. (eds.) Post-Panslavismus. Slavizitat, Slavische Idee und Antislavismus im 20. und 21. Jahrhundert (Wallstein Verlag, 2014)

- Agnew H. Origins of the Czech National Renascence (University of Pittsburgh Press, 1993)

- Carole R. The Slovenes and Yugoslavism, 1890-1914 (Columbia University Press, 1977)

- Abbott G. European and Muscovite: Ivan Kireevsky and the origins of Slavophilism (Cambridge University Press, 1972)

- Djokic D. (ed.) Yugoslavism. Histories of a Failed Idea, 1918-1992 (Hurst and Company, 2003)

- Snyder, Louis L. Encyclopedia of Nationalism (1990) pp 309–315.

- Vyšný, Paul. Neo-Slavism and the Czechs, 1898-1914 (Cambridge University Press, 1977).

- Yiǧit Gülseven, Aslı (26 October 2016). "Rethinking Russian pan-Slavism in the Ottoman Balkans: N.P. Ignatiev and the Slavic Benevolent Committee (1856–77)". Middle Eastern Studies. 53 (3): 332–348. doi:10.1080/00263206.2016.1243532. hdl:11693/37207. ISSN 0026-3206. S2CID 220378577.

- "Pan-Slavism" in Columbia Encyclopedia

- Osmańczyk, Edmund Jan (2003). "Pan-Slavism". Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: N to S. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1762–. ISBN 9780415939232. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas Valentine (2006). A History of Russia (6th ed.). US: Oxford University Press. p. 450. ISBN 978-0-19-512179-7. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Grigorieva, Anna A. (2010). "Pan-Slavism in Central and Southeastern Europe" (PDF). Journal of Siberian Federal University. Humanities & Social Sciences. 3 (1): 13–21. Retrieved 22 September 2018.