This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2012) |

Oxy-fuel welding torch (commonly called oxyacetylene welding, oxy welding, or gas welding in the United States) and oxy-fuel cutting are processes that use fuel gases (or liquid fuels such as gasoline or petrol, diesel, biodiesel, kerosene, etc) and oxygen to weld or cut metals. French engineers Edmond Fouché and Charles Picard became the first to develop oxygen-acetylene welding in 1903.[1] Pure oxygen, instead of air, is used to increase the flame temperature to allow localized melting of the workpiece material (e.g. steel) in a room environment.

A common propane/air flame burns at about 2,250 K (1,980 °C; 3,590 °F),[2] a propane/oxygen flame burns at about 2,526 K (2,253 °C; 4,087 °F),[3] an oxyhydrogen flame burns at 3,073 K (2,800 °C; 5,072 °F) and an acetylene/oxygen flame burns at about 3,773 K (3,500 °C; 6,332 °F).[4]

During the early 20th century, before the development and availability of coated arc welding electrodes in the late 1920s that were capable of making sound welds in steel, oxy-acetylene welding was the only process capable of making welds of exceptionally high quality in virtually all metals in commercial use at the time. These included not only carbon steel but also alloy steels, cast iron, aluminium, and magnesium. In recent decades it has been superseded in almost all industrial uses by various arc welding methods offering greater speed and, in the case of gas tungsten arc welding, the capability of welding very reactive metals such as titanium.

Oxy-acetylene welding is still used for metal-based artwork and in smaller home-based shops, as well as situations where accessing electricity (e.g., via an extension cord or portable generator) would present difficulties. The oxy-acetylene (and other oxy-fuel gas mixtures) welding torch remains a mainstay heat source for manual brazing, as well as metal forming, preparation, and localized heat treating. In addition, oxy-fuel cutting is still widely used, both in heavy industry and light industrial and repair operations.

In oxy-fuel welding, a welding torch is used to weld metals. Welding metal results when two pieces are heated to a temperature that produces a shared pool of molten metal. The molten pool is generally supplied with additional metal called filler. Filler material selection depends upon the metals to be welded.

In oxy-fuel cutting, a torch is used to heat metal to its kindling temperature. A stream of oxygen is then trained on the metal, burning it into a metal oxide that flows out of the kerf as dross.[5]

Torches that do not mix fuel with oxygen (combining, instead, atmospheric air) are not considered oxy-fuel torches and can typically be identified by a single tank (oxy-fuel cutting requires two isolated supplies, fuel and oxygen). Most metals cannot be melted with a single-tank torch. Consequently, single-tank torches are typically suitable for soldering and brazing but not for welding.

Uses

editOxy-fuel torches are or have been used for:

- Heating metal: in automotive and other industries for the purposes of loosening seized fasteners.

- Neutral flame is used for joining and cutting of all ferrous and non-ferrous metals except brass.

- Depositing metal to build up a surface, as in hardfacing.

- Also, oxy-hydrogen flames are used:

- In stone working for "flaming" where the stone is heated and a top layer crackles and breaks. A steel circular brush is attached to an angle grinder and used to remove the first layer leaving behind a bumpy surface similar to hammered bronze.

- In the glass industry for "fire polishing".

- In jewelry production for "water welding" using a water torch (an oxyhydrogen torch whose gas supply is generated immediately by electrolysis of water).

- In automotive repair, removing a seized bolt.

- Formerly, to heat lumps of quicklime to obtain a bright white light called limelight, in theatres or optical ("magic") lanterns.

- Formerly, in platinum works, as platinum is fusible only in the oxyhydrogen flame[citation needed] and in an electric furnace.

In short, oxy-fuel equipment is quite versatile, not only because it is preferred for some sorts of iron or steel welding but also because it lends itself to brazing, braze-welding, metal heating (for annealing or tempering, bending or forming), rust, or scale removal, the loosening of corroded nuts and bolts, and is a ubiquitous means of cutting ferrous metals.

Apparatus

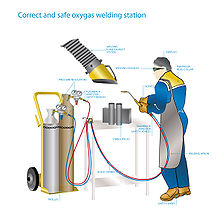

editThe apparatus used in gas welding consists basically of an oxygen source and a fuel gas source (usually contained in cylinders), two pressure regulators and two flexible hoses (one for each cylinder), and a torch. This sort of torch can also be used for soldering and brazing. The cylinders are often carried in a special wheeled trolley.

There have been examples of oxyhydrogen cutting sets with small (scuba-sized) gas cylinders worn on the user's back in a backpack harness, for rescue work, and similar.

There are also examples of both non-pressurized and pressurized liquid fuel cutting torches, usually using gasoline (petrol). These are used for their increased cutting power over gaseous fuel systems and also greater portability compared to systems requiring two high pressure tanks.

Regulator

editThe regulator ensures that pressure of the gas from the tanks matches the required pressure in the hose. The flow rate is then adjusted by the operator using needle valves on the torch. Accurate flow control with a needle valve relies on a constant inlet pressure.

Most regulators have two stages. The first stage is a fixed-pressure regulator, which releases gas from the cylinder at a constant intermediate pressure, despite the pressure in the cylinder falling as the gas in it is consumed. This is similar to the first stage of a scuba-diving regulator. The adjustable second stage of the regulator controls the pressure reduction from the intermediate pressure to the low outlet pressure. The regulator has two pressure gauges, one indicating cylinder pressure, the other indicating hose pressure. The adjustment knob of the regulator is sometimes roughly calibrated for pressure, but an accurate setting requires observation of the gauge.

Some simpler or cheaper oxygen-fuel regulators have only a single-stage regulator, or only a single gauge. A single-stage regulator will tend to allow a reduction in outlet pressure as the cylinder is emptied, requiring manual readjustment. For low-volume users, this is an acceptable simplification. Welding regulators, unlike simpler LPG heating regulators, retain their outlet (hose) pressure gauge and do not rely on the calibration of the adjustment knob. The cheaper single-stage regulators may sometimes omit the cylinder contents gauge, or replace the accurate dial gauge with a cheaper and less precise "rising button" gauge.

Gas hoses

editThe hoses are designed for use in welding and cutting metal. A double-hose or twinned design can be used, meaning that the oxygen and fuel hoses are joined. If separate hoses are used, they should be clipped together at intervals approximately 3 feet (1 m) apart, although that is not recommended for cutting applications, because beads of molten metal given off by the process can become lodged between the hoses where they are held together, and burn through, releasing the pressurized gas inside, which in the case of fuel gas usually ignites.

The hoses are color-coded for visual identification. The color of the hoses varies between countries. In the United States, the oxygen hose is green and the fuel hose is red.[6] In the UK and other countries, the oxygen hose is blue (black hoses may still be found on old equipment), and the acetylene (fuel) hose is red.[7] If liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) fuel, such as propane, is used, the fuel hose should be orange, indicating that it is compatible with LPG. LPG will damage an incompatible hose, including most acetylene hoses.

The threaded connectors on the hoses are handed to avoid accidental mis-connection: the thread on the oxygen hose is right-handed (as normal), while the fuel gas hose has a left-handed thread.[6] The left-handed threads also have an identifying groove cut into their nuts.

Gas-tight connections between the flexible hoses and rigid fittings are made by using crimped hose clips or ferrules, often referred to as 'O' clips, over barbed spigots. The use of worm-drive hose clips or Jubilee Clips is specifically forbidden in the UK and other countries.[8]

Non-return valve

editAcetylene is not just flammable; in certain conditions it is explosive. Although it has an upper flammability limit in air of 81%,[9] acetylene's explosive decomposition behaviour makes this irrelevant. If a detonation wave enters the acetylene tank, the tank will be blown apart by the decomposition. Ordinary check valves that normally prevent backflow cannot stop a detonation wave because they are not capable of closing before the wave passes around the gate. For that reason a flashback arrestor is needed. It is designed to operate before the detonation wave makes it from the hose side to the supply side.

Between the regulator and hose, and ideally between hose and torch on both oxygen and fuel lines, a flashback arrestor and/or non-return valve (check valve) should be installed to prevent flame or oxygen-fuel mixture being pushed back into either cylinder and damaging the equipment or causing a cylinder to explode.

European practice is to fit flashback arrestors at the regulator and check valves at the torch. US practice is to fit both at the regulator.

The flashback arrestor prevents shock waves from downstream coming back up the hoses and entering the cylinder, possibly rupturing it, as there are quantities of fuel/oxygen mixtures inside parts of the equipment (specifically within the mixer and blowpipe/nozzle) that may explode if the equipment is incorrectly shut down, and acetylene decomposes at excessive pressures or temperatures. In case the pressure wave has created a leak downstream of the flashback arrestor, it will remain switched off until someone resets it.

Check valve

editA check valve lets gas flow in one direction only. It is usually a chamber containing a ball that is pressed against one end by a spring. Gas flow one way pushes the ball out of the way, and a lack of flow or a reverse flow allows the spring to push the ball into the inlet, blocking it. Not to be confused with a flashback arrestor, a check valve is not designed to block a shock wave. The shock wave could occur while the ball is so far from the inlet that the wave will get past the ball before it can reach its off position.

Torch

editThe torch is the tool that the welder holds and manipulates to make the weld. It has a connection and valve for the fuel gas and a connection and valve for the oxygen, a handle for the welder to grasp, and a mixing chamber (set at an angle) where the fuel gas and oxygen mix, with a tip where the flame forms. Two basic types of torches are positive pressure type and low pressure or injector type.

Welding torch

editA welding torch head is used to weld metals. It can be identified by having only one or two pipes running to the nozzle, no oxygen-blast trigger, and two valve knobs at the bottom of the handle letting the operator adjust the oxygen and fuel flow respectively.

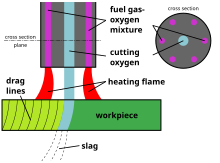

Cutting torch

editA cutting torch head is used to cut materials. It is similar to a welding torch, but can be identified by the oxygen blast trigger or lever.

When cutting, the metal is first heated by the flame until it is cherry red. Once this temperature is attained, oxygen is supplied to the heated parts by pressing the oxygen-blast trigger. This oxygen reacts with the metal, producing more heat and forming an oxide which is then blasted out of the cut. It is the heat that continues the cutting process. The cutting torch only heats the metal to start the process; further heat is provided by the burning metal.

The melting point of the iron oxide is around half that of the metal being cut. As the metal burns, it immediately turns to liquid iron oxide and flows away from the cutting zone. However, some of the iron oxide remains on the workpiece, forming a hard "slag" which can be removed by gentle tapping and/or grinding.

Rose bud torch

editA rose bud torch is used to heat metals for bending, straightening, etc. where a large area needs to be heated. It is so-called because the flame at the end looks like a rose bud. A welding torch can also be used to heat small areas such as rusted nuts and bolts.

Injector torch

editA typical oxy-fuel torch, called an equal-pressure torch, merely mixes the two gases. In an injector torch, high-pressure oxygen comes out of a small nozzle inside the torch head which drags the fuel gas along with it, using the Venturi effect.

Fuels

editOxy-fuel processes may use a variety of fuel gases (or combustible liquids), the most common being acetylene. Other gases that may be used are propylene, liquified petroleum gas (LPG), propane, natural gas, hydrogen, and MAPP gas. Liquid fuel cutting systems use such fuels as Gasoline (Petrol) Diesel, Kerosene and possibly some aviation fuels.

Acetylene

editAcetylene is the primary fuel for oxy-fuel welding and is the fuel of choice for repair work and general cutting and welding. Acetylene gas is shipped in special cylinders designed to keep the gas dissolved. The cylinders are packed with porous materials (e.g. kapok fibre, diatomaceous earth, or (formerly) asbestos), then filled to around 50% capacity with acetone, as acetylene is soluble in acetone. This method is necessary because above 207 kilopascals (30 pounds per square inch) (absolute pressure), acetylene is unstable and may explode.

There is about 1,700 kPa (247 psi) pressure in the tank when full. When combined with oxygen, acetyline burns at 3,200 to 3,500 degrees Celsius (5,790 to 6,330 degrees Fahrenheit), the highest among commonly used gaseous fuels. As a fuel, acetylene's primary disadvantage in comparison to other fuels is its high price.

As acetylene is unstable at a pressure roughly equivalent to 33 ft (10 m) underwater, water-submerged cutting and welding is reserved for hydrogen rather than acetylene.

Gasoline

editThis section contains promotional content. (March 2022) |

Tests[citation needed] showed that an oxy-gasoline torch can cut steel plate up to 0.5 in (13 mm) thick at the same rate as oxy-acetylene. In plate thicknesses greater than 0.5 in (13 mm) the cutting rate was better than that of oxy-acetylene; at 4.5 in (110 mm) it was three times faster.[10] Additionally the liquid fuel vapour is about 4x the density of a gaseous fuel. A high velocity cutting flame is produced by the huge volume expansion while the liquid transitions to a vapour so the cutting flame can cut across voids (air space between plates).

Oxy-gasoline torches can also cut through paint, dirt, rust and other contaminating surface materials coating old steel. This system provides almost 100% oxidation during cutting, leaving almost no molten steel in the slag to prevent "sticking" together cut material. Operating cost for a gasoline torch is typically 75-90% less than using propane or Acetylene.

The gasoline can be fed either from a pressurized tank (whose pressure can be hand-pumped or fed from a gas cylinder) or a non-pressurized tank, with the fuel being drawn into the torch by a venturi action created by the pressurized oxygen flow.[10] Another low cost approach commonly used by jewelry makers in Asia is using air bubbled through a gasoline container by a foot-operated air pump, and burning the fuel-air mixture in a specialized welding torch.

Diesel

editDiesel is a new option in the liquid fuel cutting torch market. Diesel torches claim several advantages over gaseous fuels and gasoline. Diesel is inherently safer and more powerful than gasoline or gaseous fuel such as acetylene and propane, and will cut steel faster and cheaper than either of those gases. In addition, the liquid fuel vapor is about 5 times the density of a gaseous fuel, providing much greater "punch". A high velocity cutting flame is produced by the huge volume expansion when the liquid transitions to a vapor, so the cutting flame will easily cut across air voids between plates. A diesel/oxygen torch can cut through paint, dirt, rust and other surface contaminants on steel. This system provides almost 100% oxidation during cutting so it leaves virtually no molten steel in the slag, preventing the "sticking together" of the cut materials. The operating cost for a diesel torch is typically 75-90% less than using propane or acetylene. Growing use in the demolition or scrap industries

Hydrogen

editHydrogen has a clean flame and is good for use on aluminium. It can be used at a higher pressure than acetylene and is therefore useful for underwater welding and cutting. It is a good type of flame to use when heating large amounts of material. The flame temperature is high, about 2,000 °C for hydrogen gas in air at atmospheric pressure,[11] and up to 2800 °C when pre-mixed in a 2:1 ratio with pure oxygen (oxyhydrogen). Hydrogen is not used for welding steels and other ferrous materials, because it causes hydrogen embrittlement.

For some oxyhydrogen torches the oxygen and hydrogen are produced by electrolysis of water in an apparatus which is connected directly to the torch. Types of this sort of torch:

- The oxygen and the hydrogen are led off the electrolysis cell separately and are fed into the two gas connections of an ordinary oxy-gas torch. This happens in the water torch, which is sometimes used in small torches used in making jewelry and electronics.

- The mixed oxygen and hydrogen are drawn from the electrolysis cell and are led into a special torch designed to prevent flashback. See oxyhydrogen.

MPS and MAPP gas

editMethylacetylene-propadiene (MAPP) gas and LPG gas are similar fuels, because LPG gas is liquefied petroleum gas mixed with MPS. It has the storage and shipping characteristics of LPG and has a heat value a little lower than that of acetylene. Because it can be shipped in small containers for sale at retail stores, it is used by hobbyists and large industrial companies and shipyards because it does not polymerize at high pressures — above 15 psi or so (as acetylene does) and is therefore much less dangerous than acetylene.

Further, more of it can be stored in a single place at one time, as the increased compressibility allows for more gas to be put into a tank. MAPP gas can be used at much higher pressures than acetylene, sometimes up to 40 or 50 psi in high-volume oxy-fuel cutting torches which can cut up to 12-inch-thick (300 mm) steel. Other welding gases that develop comparable temperatures need special procedures for safe shipping and handling. MPS and MAPP are recommended for cutting applications in particular, rather than welding applications.

On 30 April 2008 the Petromont Varennes plant closed its methylacetylene/propadiene crackers. As it was the only North American plant making MAPP gas, many substitutes were introduced by companies that had repackaged the Dow and Varennes product(s) - most of these substitutes are propylene, see below.

Propylene and fuel gas

editPropylene is used in production welding and cutting. It cuts similarly to propane. When propylene is used, the torch rarely needs tip cleaning. There is often a substantial advantage to cutting with an injector torch (see the propane section) rather than an equal-pressure torch when using propylene. Quite a few North American suppliers have begun selling propylene under proprietary trademarks such as FG2 and Fuel-Max.

Butane, propane and butane/propane mixes

editButane, like propane, is a saturated hydrocarbon. Butane and propane do not react with each other and are regularly mixed. Butane boils at 0.6 °C. Propane is more volatile, with a boiling point of -42 °C. Vaporization is rapid at temperatures above the boiling points. The calorific (heat) values of the two are almost equal. Both are thus mixed to attain the vapor pressure that is required by the end user and depending on the ambient conditions. If the ambient temperature is very low, propane is preferred to achieve higher vapor pressure at the given temperature.[citation needed]

Propane does not burn as hot as acetylene in its inner cone, and so it is rarely used for welding.[12] Propane, however, has a very high number of BTUs per cubic foot in its outer cone, and so with the right torch (injector style) can make a faster and cleaner cut than acetylene, and is much more useful for heating and bending than acetylene.

The maximum neutral flame temperature of propane in oxygen is 2,822 °C (5,112 °F).[13]

Propane is cheaper than acetylene and easier to transport.[14]

Operating costs

editThis article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: obsolete and proprietary non matching information. (December 2022) |

The following is a comparison of operating costs in cutting 1⁄2 in (13 mm) plate. Costing is based on an average cost for oxygen and different fuels in May 2012.[obsolete source] The opex with Gasoline was 25% that of propane and 10% that of acetylene. Numbers will vary depending on source of oxygen or fuel and on the type of cutting and the cutting environment or situation.[15]

| Gasoline | Acetylene | Propane | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel consumption, litres per minute | 0.012 | 3.5 | 4.5 |

| Fuel consumption, litres per hour | 0.72 | 210 | 270 |

| Oxygen consumption, litres per minute | 23 | 30 | 58 |

| Millimetres cut per minute | 550 | 350 | 500 |

| Fuel cost per hour | $0.548 | $35.079 | $7.852 |

| Oxygen cost per hour | $7.80 | $10.17 | $19.67 |

| Total per hour | $8.347 | $45.252 | $27.52 |

| Metres cut per hour | 16.51 | 10.51 | 15.01 |

| Feet cut per hour | 54.16 | 34.47 | 49.24 |

| Cutting cost per foot | $0.15 | $1.31 | $0.56 |

| Cost to cut 100 ft | $15.41 | $131.30 | $55.89 |

The role of oxygen

editOxygen is not the fuel. It is the oxidizing agent, which chemically combines with the fuel to produce the heat for welding. This is called 'oxidation', but the more specific and more commonly used term in this context is 'combustion'. In the case of hydrogen, the product of combustion is simply water. For the other hydrocarbon fuels, water and carbon dioxide are produced. The heat is released because the molecules of the products of combustion have a lower energy state than the molecules of the fuel and oxygen. In oxy-fuel cutting, oxidation of the metal being cut (typically iron) produces nearly all of the heat required to "burn" through the workpiece.

Oxygen is usually produced elsewhere by distillation of liquefied air and shipped to the welding site in high-pressure vessels (commonly called "tanks" or "cylinders") at a pressure of about 21,000 kPa (3,000 lbf/in² = 200 atmospheres). It is also shipped as a liquid in Dewar type vessels (like a large Thermos jar) to places that use large amounts of oxygen.

It is also possible to separate oxygen from air by passing the air, under pressure, through a zeolite sieve that selectively adsorbs the nitrogen and lets the oxygen (and argon) pass. This gives a purity of oxygen of about 93%. This method works well for brazing, but higher-purity oxygen is necessary to produce a clean, slag-free kerf when cutting.

Types of flame

editThe welder can adjust the oxy-acetylene flame to be carburizing (aka reducing), neutral, or oxidizing. Adjustment is made by adding more or less oxygen to the acetylene flame. The neutral flame is the flame most generally used when welding or cutting. The welder uses the neutral flame as the starting point for all other flame adjustments because it is so easily defined. This flame is attained when welders, as they slowly open the oxygen valve on the torch body, first see only two flame zones. At that point, the acetylene is being completely burned in the welding oxygen and surrounding air.[5] The flame is chemically neutral.

The two parts of this flame are the light blue inner cone and the darker blue to colorless outer cone. The inner cone is where the acetylene and the oxygen combine. The tip of this inner cone is the hottest part of the flame. It is approximately 6,000 °F (3,320 °C) and provides enough heat to easily melt steel.[5] In the inner cone the acetylene breaks down and partly burns to hydrogen and carbon monoxide, which in the outer cone combine with more oxygen from the surrounding air and burn.

An excess of acetylene creates a reducing (sometimes called carbonizing) flame. This flame is characterized by three flame zones; the hot inner cone, a white-hot "acetylene feather", and the blue-colored outer cone. This is the type of flame observed when oxygen is first added to the burning acetylene. The feather is adjusted and made ever smaller by adding increasing amounts of oxygen to the flame. A welding feather is measured as 2X or 3X, with X being the length of the inner flame cone.

The unburned carbon insulates the flame and drops the temperature to approximately 5,000 °F (2,760 °C). The reducing flame is typically used for hardfacing operations or backhand pipe welding techniques. The feather is caused by incomplete combustion of the acetylene to cause an excess of carbon in the flame. Some of this carbon is dissolved by the molten metal to carbonize it. The carbonizing flame will tend to remove the oxygen from iron oxides which may be present, a fact which has caused the flame to be known as a "reducing flame".[5]

The oxidizing flame is the third possible flame adjustment. It occurs when the ratio of oxygen to acetylene required for a neutral flame has been changed to give an excess of oxygen. This flame type is observed when welders add more oxygen to the neutral flame. This flame is hotter than the other two flames because the combustible gases will not have to search so far to find the necessary amount of oxygen, nor heat up as much thermally inert carbon.[5] It is called an oxidizing flame because of its effect on metal. This flame adjustment is generally not preferred. The oxidizing flame creates undesirable oxides to the structural and mechanical detriment of most metals. In an oxidizing flame, the inner cone acquires a purplish tinge and gets pinched and smaller at the tip, and the sound of the flame gets harsh. A slightly oxidizing flame is used in braze-welding and bronze-surfacing while a more strongly oxidizing flame is used in fusion welding certain brasses and bronzes[5]

The size of the flame can be adjusted to a limited extent by the valves on the torch and by the regulator settings, but in the main it depends on the size of the orifice in the tip. In fact, the tip should be chosen first according to the job at hand, and then the regulators set accordingly.

Welding

editThe flame is applied to the base metal and held until a small puddle of molten metal is formed. The puddle is moved along the path where the weld bead is desired. Usually, more metal is added to the puddle as it is moved along by dipping metal from a welding rod or filler rod into the molten metal puddle. The metal puddle will travel towards where the metal is the hottest. This is accomplished through torch manipulation by the welder.

The amount of heat applied to the metal is a function of the welding tip size, the speed of travel, and the welding position. The flame size is determined by the welding tip size. The proper tip size is determined by the metal thickness and the joint design.

Welding gas pressures using oxy-acetylene are set in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations. The welder will modify the speed of welding travel to maintain a uniform bead width. Uniformity is a quality attribute indicating good workmanship. Trained welders are taught to keep the bead the same size at the beginning of the weld as at the end. If the bead gets too wide, the welder increases the speed of welding travel. If the bead gets too narrow or if the weld puddle is lost, the welder slows down the speed of travel. Welding in the vertical or overhead positions is typically slower than welding in the flat or horizontal positions.

The welder must add the filler rod to the molten puddle. The welder must also keep the filler metal in the hot outer flame zone when not adding it to the puddle to protect filler metal from oxidation. Do not let the welding flame burn off the filler metal. The metal will not wet into the base metal and will look like a series of cold dots on the base metal. There is very little strength in a cold weld. When the filler metal is properly added to the molten puddle, the resulting weld will be stronger than the original base metal.

Welding lead or 'lead burning' was much more common in the 19th century to make some pipe connections and tanks. Great skill is required, but it can be quickly learned.[16] In building construction today some lead flashing is welded but soldered copper flashing is much more common in America. In the automotive body repair industry before the 1980s, oxyacetylene gas torch welding was seldom used to weld sheet metal, since warping was a byproduct as well as excess heat. Automotive body repair methods at the time were crude and yielded improprieties until MIG welding became the industry standard. Since the 1970s, when high strength steel became the standard for automotive manufacturing, electric welding became the preferred method. After the 1980s, oxyacetylene torches fell out of use for sheet metal welding in the industrialized world.

Cutting

editFor cutting, the setup is a little different. A cutting torch has a 60- or 90-degree angled head with orifices placed around a central jet. The outer jets are for preheat flames of oxygen and acetylene. The central jet carries only oxygen for cutting. The use of several preheating flames rather than a single flame makes it possible to change the direction of the cut as desired without changing the position of the nozzle or the angle which the torch makes with the direction of the cut, as well as giving a better preheat balance.[5] Manufacturers have developed custom tips for Mapp, propane, and propylene gases to optimize the flames from these alternate fuel gases.

The flame is not intended to melt the metal, but to bring it to its ignition temperature.

The torch's trigger blows extra oxygen at higher pressures down the torch's third tube out of the central jet into the workpiece, causing the metal to burn and blowing the resulting molten oxide through to the other side. The ideal kerf is a narrow gap with a sharp edge on either side of the workpiece; overheating the workpiece and thus melting through it causes a rounded edge.

Cutting is initiated by heating the edge or leading face (as in cutting shapes such as round rod) of the steel to the ignition temperature (approximately bright cherry red heat) using the pre-heat jets only, then using the separate cutting oxygen valve to release the oxygen from the central jet.[5] The oxygen chemically combines with the iron in the ferrous material to oxidize the iron quickly into molten iron oxide, producing the cut. Initiating a cut in the middle of a workpiece is known as piercing.

It is worth noting several things at this point:

- The oxygen flow rate is critical; too little will make a slow ragged cut, while too much will waste oxygen and produce a wide concave cut. Oxygen lances and other custom made torches do not have a separate pressure control for the cutting oxygen, so the cutting oxygen pressure must be controlled using the oxygen regulator. The oxygen cutting pressure should match the cutting tip oxygen orifice. The tip manufacturer's equipment data should be reviewed for the proper cutting oxygen pressures for the specific cutting tip.[5]

- The oxidation of iron by this method is highly exothermic. Once it has started, steel can be cut at a surprising rate, far faster than if it were merely melted through. At this point, the pre-heat jets are there purely for assistance. The rise in temperature will be obvious by the intense glare from the ejected material, even through proper goggles. A thermal lance is a tool that also uses rapid oxidation of iron to cut through almost any material.

- Since the melted metal flows out of the workpiece, there must be room on the opposite side of the workpiece for the spray to exit. When possible, pieces of metal are cut on a grate that lets the melted metal fall freely to the ground. The same equipment can be used for oxyacetylene blowtorches and welding torches, by exchanging the part of the torch in front of the torch valves.

For a basic oxy-acetylene rig, the cutting speed in light steel section will usually be nearly twice as fast as a petrol-driven cut-off grinder. The advantages when cutting large sections are obvious: an oxy-fuel torch is light, small and quiet and needs very little effort to use, whereas an angle grinder is heavy and noisy and needs considerable operator exertion and may vibrate severely, leading to stiff hands and possible long-term vibration white finger. Oxy-acetylene torches can easily cut through ferrous materials in excess of 200 mm (7.9 in). Oxygen lances are used in scrapping operations and cut sections thicker than 200 mm. Cut-off grinders are useless for these kinds of application.

Robotic oxy-fuel cutters sometimes use a high-speed divergent nozzle. This uses an oxygen jet that opens slightly along its passage. This allows the compressed oxygen to expand as it leaves, forming a high-velocity jet that spreads less than a parallel-bore nozzle, allowing a cleaner cut. These are not used for cutting by hand since they need very accurate positioning above the work. Their ability to produce almost any shape from large steel plates gives them a secure future in shipbuilding and in many other industries.

Oxy-propane torches are usually used for cutting up scrap to save money, as LPG is far cheaper joule for joule than acetylene, although propane does not produce acetylene's very neat cut profile. Propane also finds a place in production, for cutting very large sections.

Oxy-acetylene can cut only low- to medium-carbon steels and wrought iron. High-carbon steels are difficult to cut because the melting point of the slag is closer to the melting point of the parent metal, so that the slag from the cutting action does not eject as sparks but rather mixes with the clean melt near the cut. This keeps the oxygen from reaching the clean metal and burning it. In the case of cast iron, graphite between the grains and the shape of the grains themselves interfere with the cutting action of the torch. Stainless steels cannot be cut either because the material does not burn readily.[17]

Safety

editOxyacetylene welding/cutting is generally considered not to be difficult, but there are a good number of subtle safety points that should be learned such as:

- More than 1/7 the capacity of the cylinder should not be used per hour. This causes the acetone inside the acetylene cylinder to come out of the cylinder and contaminate the hose and possibly the torch.

- Acetylene is dangerous above 1 atm (15 psi) pressure. It is unstable and explosively decomposes.

- Proper ventilation when welding will help to avoid large chemical exposure.

Eye protection

editProper protection such as welding goggles should be worn at all times, including to protect the eyes against glare and flying sparks. Special safety eyewear must be used—both to protect the welder and to provide a clear view through the yellow-orange flare given off by the incandescing flux. In the 1940s cobalt melters’ glasses were borrowed from steel foundries and were still available until the 1980s.

However, the lack of protection from impact, ultra-violet, infrared and blue light caused severe eyestrain and eye damage. Didymium eyewear, developed for glassblowers in the 1960s, was also borrowed—until many complained of eye problems from excessive infrared, blue light, and insufficient shading. Today very good eye protection can be found designed especially for gas-welding aluminum that cuts the sodium orange flare completely and provides the necessary protection from ultraviolet, infrared, blue light and impact, according to ANSI Z87-1989 safety standards for a Special Purpose Lens.[18]

Safety with cylinders

editFuel and oxygen tanks should be fastened securely and upright to a wall, post, or portable cart. An oxygen tank is especially dangerous because the gas is stored at a pressure of 21 MPa (3,000 psi; 210 atm)) when full. If the tank falls over and damages the valve, the tank can be jettisoned by the compressed oxygen escaping the cylinder at high speed. Tanks in this state are capable of breaking through a brick wall.[19] For this reason, an oxygen tank should never be moved around without its valve cap screwed in place.

On an oxyacetylene torch system there are three types of valves: the tank valve, the regulator valve, and the torch valve. Each gas in the system will have each of these three valves. The regulator converts the high pressure gas inside of the tanks to a low pressure stream suitable for welding. Acetylene cylinders must be maintained in an upright position to prevent the internal acetone and acetylene from separating in the filler material.[20]

Chemical exposure

editA less obvious hazard of welding is exposure to harmful chemicals. Exposure to certain metals, metal oxides, or carbon monoxide can often lead to severe medical conditions. Damaging chemicals can be produced from the fuel, from the work-piece, or from a protective coating on the work-piece. By increasing ventilation around the welding environment, exposure to harmful chemicals are significantly reduced from any source.

The most common fuel used in welding is acetylene, which has a two-stage reaction. The primary chemical reaction involves the acetylene disassociating in the presence of oxygen to produce heat, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen gas: C2H2 + O2 → 2CO + H2. A secondary reaction follows where the carbon monoxide and hydrogen combine with more oxygen to produce carbon dioxide and water vapor. When the secondary reaction does not burn all of the reactants from the primary reaction, the welding process can often produce large amounts of carbon monoxide. Carbon monoxide is also the byproduct of many other incomplete fuel reactions.

Almost every piece of metal is an alloy of one type or another. Copper, aluminum, and other base metals are occasionally alloyed with beryllium, which is a highly toxic metal. When a metal like this is welded or cut, high concentrations of toxic beryllium fumes are released. Long-term exposure to beryllium may result in shortness of breath, chronic cough, and significant weight loss, accompanied by fatigue and general weakness. Other alloying elements such as arsenic, manganese, silver, and aluminum can cause sickness to those who are exposed.

More common are the anti-rust coatings on many manufactured metal components. Zinc, cadmium, and fluorides are often used to protect irons and steels from oxidizing. Galvanized metals have a very heavy zinc coating. Exposure to zinc oxide fumes can lead to a sickness named "metal fume fever". This condition rarely lasts longer than 24 hours, but severe cases can be fatal.[21] Not unlike common influenza, fevers, chills, nausea, cough, and fatigue are common effects of high zinc oxide exposure.

Flashback

editFlashback is the condition of the flame propagating down the hoses of an oxy-fuel welding and cutting system. To prevent such a situation a flashback arrestor is usually employed.[22] The flame burns backwards into the hose, causing a popping or squealing noise. It can cause an explosion in the hose with the potential to injure or kill the operator. Using a lower pressure than recommended can cause a flashback.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Carlisle, Rodney (2004). Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries, p.365. John Wright & Songs, Inc., New Jersey. ISBN 0-471-24410-4.

- ^ Lide, David R. (2004-06-29). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 85th Edition. CRC Press. pp. 15–52. ISBN 9780849304859.

- ^ "Adiabatic Flame Temperature". www.engineeringtoolbox.com. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ Basic Mech Engg,3E Tnc Syllb. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. 2000-05-01. p. 106. ISBN 9780074636626.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The Oxy-Acetylene Handbook, Union Carbide Corp 1975

- ^ a b "Fundamentals of Professional Welding". 23 April 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-04-23.

- ^ "Safety in gas welding, cutting and similar processes" (PDF). HSE. p. 5.

- ^ "Portable Oxy-Fuel Gas Equipment" (PDF). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ^ "Special Hazards of Acetylene". US MSHA. Archived from the original on 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2012-01-07.

- ^ a b "Oxy-Gasoline Torch" (PDF). www.dndkm.org. Retrieved 2024-05-20.

- ^ William Augustus Tilden (January 1999). Chemical Discovery and Invention in the Twentieth Century. Adamant Media Corporation. p. 80. ISBN 0-543-91646-4.

- ^ Jeffus 1997, p. 742

- ^ "DH3 Lightweight Gas Cutting & Welding Torches". AES Industrial Supplies Limited. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ^ "Gas Cutting Torches". AES Industrial Supplies Limited. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ^ davco.biz, "DAVCO SUPACUT Oxy-Petrol/Gasoline Cutting Systems", Retrieved 2022-12-23

- ^ Davies, J. H.. Modern methods of welding as applied to workshop practice, describing various methods: oxy-acetylene welding, electric seam welding ... eye protection in welding operations [etc.] .... New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1922. Print. Chapter 2 Lead Burning, 6-12.

- ^ Miller 1916, p. 270

- ^ White, Kent (2008), Authentic Aluminum Gas Welding: The Method Revived, TM Technologies

- ^ "Air Cylinder Rocket." MythBusters Discovery Channel, October 18, 2006.

- ^ "Oxygen And Acetylene Use And Safety - AR Training" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2015-10-03.

- ^ "Zinc Metal Fume Fever : A Case Study : Blacksmithing How-to on anvilfire iForge". www.anvilfire.com.

- ^ Swift, P.; Murray, J. (2008). FCS Welding L2. Pearson South Africa. p. 286. ISBN 978-1-77025-226-4.

Bibliography

edit- Miller, Samuel Wylie (1916). Oxy-acetylene Welding. The Industrial Press.

- Jeffus, Larry F. (1997). Welding: Principles and Applications (4th, illustrated ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-8273-8240-4.

Further reading

edit- Althouse; Turnquist; Bowditch (1970). Modern Welding. Goodheart - Willcox. ISBN 9780870061097.

- The Welding Encyclopedia (ninth ed.). The Welding Engineer staff. 1938.

External links

edit- "Welding and Cutting with Oxyacetylene" Popular Mechanics, December 1935 pp. 948–953

- Using Oxy-Fuel Welding on Aircraft Aluminum Sheet

- More on oxyacetylene

- welding history at Welding.com

- An e-book about oxy-gas cutting and welding

- Oxy-fuel torch at Everything2.com

- Torch Brazing Information

- Video of how to weld lead sheet

- Working with lead sheet