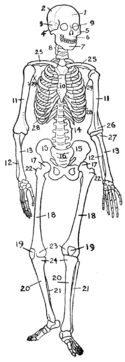

Osteology (from Greek ὀστέον (ostéon) 'bones' and λόγος (logos) 'study') is the scientific study of bones, practised by osteologists. A subdiscipline of anatomy, anthropology, and paleontology, osteology is the detailed study of the structure of bones, skeletal elements, teeth, microbone morphology, function, disease, pathology, the process of ossification from cartilaginous molds, and the resistance and hardness of bones (biophysics).[1]

Osteologists frequently work in the public and private sector as consultants for museums, scientists for research laboratories, scientists for medical investigations and/or for companies producing osteological reproductions in an academic context.

Osteology and osteologists should not be confused with the pseudoscientific practice of osteopathy and its practitioners, osteopaths.

Methods

editA typical analysis will include:

- an inventory of the skeletal elements present

- a dental inventory

- aging data, based upon epiphyseal fusion and dental eruption (for subadults) and deterioration of the pubic symphysis or sternal end of ribs (for adults)

- stature and other metric data

- ancestry

- non-metric traits

- pathology and/or cultural modifications

Applications

editOsteological approaches are frequently applied to investigations in disciplines such as vertebrate paleontology, zoology, forensic science, physical anthropology, and archaeology. It has been shown that osteological characters have greater consistency with molecular phylogenies than non-osteological (soft tissue) characters, implying that they may be more reliable in reconstructing evolutionary history.[2] Osteology has a place in research on topics including:

- Ancient warfare

- Activity patterns

- Criminal investigations

- Demography

- Developmental biology

- Diet

- Disease

- Genetics of early populations

- Fossil assemblages

- Health

- Human migration

- Identification of unknown remains

- Physique

- Social inequality

- War crimes

Human osteology and forensic anthropology

editExamination of human osteology is often used in forensic anthropology, which is usually used to identify age, death, sex, growth, and development of human remains and can be used in a biocultural context.

There are four factors leading to variation in skeletal anatomy: ontogeny (or growth), sexual dimorphism, geographic variation and individual, or idiosyncratic, variation.[3]

Osteology can also determine an individual's ancestry, race or ethnicity. Historically, humans were typically grouped into three outdated race groups: caucasoids, mongoloids and negroids. However, this classification system is growing less reliable due to interancestrial marriages increases and markers become less defined.[4] Determination of ancestry is controversial, but can give an understandable label to define the ancestry of an unidentified body or skeleton.[5]

Crossrail Project

editOne example of osteology and its various applications is illustrated by the Crossrail Project. An endeavor by the city of London to expand their railway system inadvertently uncovered 25 human skeletons at Charterhouse Square in 2013. Although archaeological excavation of the skeletons temporarily halted further advances in the railway system, they have given way to new, possibly revolutionary, discoveries in the field of archaeology.

These 25 skeletal remains, along with many more that were found in further searches, are believed to be from the mass graves dug to bury the millions of victims of the Black Death in the 14th century. Archaeologists and forensic scientists have used osteology to examine the condition of the skeletal remains, to help piece together the reason why the Black Death had such a detrimental effect on the European population. It was discovered that most of the population was in generally poor health to begin with. Through extensive analysis of the bones, it was discovered that many of the inhabitants of Great Britain were plagued with rickets, anemia, and malnutrition.[6] There has also been frequent evidence that much of the population had traces of broken bones from frequent fighting and hard labor.

This archaeological project has been named the Crossrail Project. Archaeologists will continue to excavate and search for remains to help uncover missing pieces of history. These advances in our understanding of the past will be improved by the study of other skeletons buried in the same area.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Blau, Soren (2014). "Osteology: Definition". Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer. p. 5641. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_127. ISBN 978-1-4419-0465-2.

- ^ Leah M Callender-Crowe; Robert S Sansom (2022). "Osteological characters of birds and reptiles are more congruent with molecular phylogenies than soft characters are". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 194 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa136.

- ^ White, Tim D.; Black, Michael T.; Folkens, Pieter A. (2011). Human Osteology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-092085-6.

- ^ "Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body: Education: Anthropological Views". www.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ "Forensic Anthropology and Race | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com.

- ^ McCoy, Terrence. "Everything you know about the Black Death is wrong". The Washington Post. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

References

edit- Bass, W. M. 2005. Human Osteology: A Laboratory and Field Manual. 5th Edition. Columbia: Missouri Archaeological Society.

- Buikstra, J. E. and Ubelaker, D. H. (eds.) 1994. Standards for Data Collection from Human Skeletal Remains. Arkansas Archeological Survey Research Series No. 44.

- Cox, M and Mays, S. (eds.) 2000. Human Osteology in Archaeology and Forensic Science. London: Greenwich Medical Media.

- F.F.A. Ijpma, H.J. ten Duis, T.M. van Guilik 2012." A cornerstone of orthopaedic education". Bones & Joint 360, Vol. 1, No. 6

- Ekezie, Jervas, PHD, "Bone, the Frame of Human Classification: The Core of Anthropology". Department of Anatomy, School of Basic Medical Sciences, Federal University of Technology, PMB 1526, Owerri, Nigeria. Volume 2: Issue 1.