In classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex (also spelled Œdipus complex) refers to a son's sexual attitude towards his mother and concomitant hostility toward his father, first formed during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. A daughter's attitude of desire for her father and hostility toward her mother is referred to as the feminine Oedipus complex.[1] The general concept was considered by Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), although the term itself was introduced in his paper A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men (1910).[2][3]

Freud's ideas of castration anxiety and penis envy refer to the differences of the sexes in their experience of the Oedipus complex.[4] The complex is thought to persist into adulthood as an unconscious psychic structure which can assist in social adaptation but also be the cause of neurosis. According to sexual difference, a positive Oedipus complex refers to the child's sexual desire for the opposite-sex parent and aversion to the same-sex parent, while a negative Oedipus complex refers to the desire for the same-sex parent and aversion to the opposite-sex parent.[3][5][6] Freud considered that the child's identification with the same-sex parent is the socially acceptable outcome of the complex. Failure to move on from the compulsion to satisfy a basic desire and to reconcile with the same-sex parent leads to neurosis.

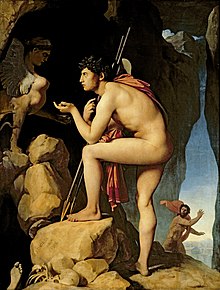

The theory is named for the mythological figure Oedipus, an ancient Theban king who discovers he has unknowingly murdered his father and married his mother, whose depiction in Sophocles' Oedipus Rex had a profound influence on Freud. Freud rejected the term Electra complex,[7] introduced by Carl Jung in 1913[8] as a proposed equivalent complex among young girls.[7]

Some critics have argued that Freud, by abandoning his earlier seduction theory (which attributed neurosis to childhood sexual abuse) and replacing it with the theory of the Oedipus complex, instigated a cover-up for sexual abuse of children. Some scholars and psychologists have criticized the theory for being incapable of applying to same-sex parents, and as being incompatible with the widespread aversion to incest.

Background

editOedipus refers to a 5th-century BC Greek mythological character Oedipus, who unknowingly kills his father, Laius, and marries his mother, Jocasta. A play based on the myth, Oedipus Rex, was written by Sophocles, c. 429 BC.

Modern productions of Sophocles' play were staged in Paris and Vienna in the 19th century and were phenomenally successful in the 1880s and 1890s. The Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) attended. In his book The Interpretation of Dreams, first published in 1899, he proposes that an Oedipal desire is a universal psychological phenomenon innate (phylogenetic) to human beings, and the cause of much unconscious guilt.

Freud believed that the Oedipal sentiment has been inherited through the millions of years it took for humans to evolve from apes.[10] His view of its universality was based on his clinical observation of neurotic or normal children, his analysis of his own response to Oedipus Rex, and on the fact that the play was effective on both ancient and modern audiences. Freud describes the Oedipus myth's timeless appeal thus:

His destiny moves us only because it might have been ours — because the Oracle laid the same curse upon us before our birth as upon him. It is the fate of all of us, perhaps, to direct our first sexual impulse towards our mother and our first hatred and our first murderous wish against our father. Our dreams convince us that this is so.[11]

Freud also claims that the play Hamlet "has its roots in the same soil as Oedipus Rex", and that the differences between the two plays are revealing:

In [Oedipus Rex] the child's wishful fantasy that underlies it is brought into the open and realized as it would be in a dream. In Hamlet it remains repressed; and—just as in the case of a neurosis—we only learn of its existence from its inhibiting consequences.[12][13]

However, in The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud makes it clear that the "primordial urges and fears" that are his concern and the basis of the Oedipal complex are inherent in the myths the play is based on, not primarily in the play itself, which Freud refers to as a "further modification of the legend" that originates in a "misconceived secondary revision of the material, which has sought to exploit it for theological purposes".[14][15][16]

Before the idea of the Oedipus complex, Freud believed that childhood sexual trauma was the cause of neurosis. This idea, sometimes called Freud's seduction theory, was deemphasized in favor of the Oedipus complex around 1897.[17]

Timeline

edit- 1896. Freud publishes The Aetiology of Hysteria. The paper was criticized for theorizing that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse.

- 1897–1909. After his father's death in 1896, and having seen the play Oedipus Rex, by Sophocles, Freud begins using the term "Oedipus". As Freud wrote in an 1897 letter, "I found in myself a constant love for my mother, and jealousy of my father. I now consider this to be a universal event in early childhood."[18]

- 1909–1914. Proposes that Oedipal desire is the "nuclear complex" of all neuroses; first usage of "Oedipus complex" in 1910.

- 1914–1918. Considers paternal and maternal incest.

- 1919–1926. Complete Oedipus complex; identification and bisexuality are conceptually evident in later works.

- 1926–1931. Applies the Oedipal theory to religion and custom.

- 1931–1938. Investigates the "feminine Oedipus attitude" and "negative Oedipus complex"; later the "Electra complex".[19]

The Oedipus complex

editOriginal formulation

editFreud's original examples of the Oedipus complex are applied only to boys or men; he never fully clarified his views on the nature of the complex in girls.[20] He described the complex as a young boy's hatred or desire to eliminate his father and to have sex with his mother.

Freud introduced the term "Oedipus complex" in a 1910 article titled A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men.[20][2] It appears in a section of this paper describing what happens after a boy first becomes aware of prostitution:

When after this he can no longer maintain the doubt which makes his parents an exception to the universal and odious norms of sexual activity, he tells himself with cynical logic that the difference between his mother and a whore is not after all so very great, since basically they do the same thing. The enlightening information he has received has in fact awakened the memory-traces of the impressions and wishes of his early infancy, and these have led to a reactivation in him of certain mental impulses. He begins to desire his mother herself in the sense with which he has recently become acquainted, and to hate his father anew as a rival who stands in the way of this wish; he comes, as we say, under the dominance of the Oedipus complex. He does not forgive his mother for having granted the favour of sexual intercourse not to himself but to his father, and he regards it as an act of unfaithfulness.[21]

Freud and others eventually extended this idea and embedded it in a larger body of theory.

Later theory

editIn classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex occurs during the phallic stage of psychosexual development (age 3–6 years), although it can manifest at an earlier age.[22][23]

In the phallic stage, a boy's decisive psychosexual experience is the Oedipus complex—his son–father competition for possession of his mother. It is in this third stage of psychosexual development that the child's genitalia is his or her primary erogenous zone; thus, when children become aware of their bodies, the bodies of other children, and the bodies of their parents, they gratify physical curiosity by undressing and exploring themselves, each other, and their genitals, so learning the anatomic differences between male and female and the gender differences between boy and girl.

Despite the mother being the parent who primarily gratifies the child's desires, the child begins forming a discrete sexual identity—"boy", "girl"—that alters the dynamics of the parent and child relationship; the parents become objects of infantile libidinal energy. The boy directs his libido (sexual desire) toward his mother and directs jealousy and emotional rivalry against his father. The boy's desire for his mother is concomitant with a desire for the death of his father and even an impulse to instigate that death. These desires manifest in the realm of the id, governed by the pleasure principle, but the pragmatic ego, governed by the reality principle, knows that the father is an impossible rival to overcome and the impulse is repressed. The boy's ambivalence about his father's place in the family, is manifested as fear of castration by the physically superior father; the fear is an irrational, subconscious manifestation of the infantile id.[24]

In both sexes, defense mechanisms provide transitory resolutions of the conflict between the drives of the id and the drives of the ego. Repression, the blocking of unacceptable ideas and impulses from the conscious mind, is the first defence mechanism, but its action does not resolve the id–ego conflict; it merely confines the impulse in the unconscious, where it continues to exert pressure in the direction of consciousness. The second defense mechanism is identification, in which the child adapts by incorporating, into his or her (super)ego, the personality characteristics of the same-sex parent. In the case of the boy, this diminishes his castration anxiety, because his likeness to his father protects him from the consequences of their rivalry. The little girl's anxiety is diminished in her identification with the mother, who understands that neither of them possesses a penis, and thus are not antagonists.[25]

The satisfactory resolution of the Oedipus complex is considered important in developing the male infantile super-ego. By identifying with the father, the boy internalizes social morality, thereby potentially becoming a voluntary, self-regulating follower of societal rules, rather than merely reflexively complying out of fear of punishment. Unresolved son–father competition for the psychosexual possession of the mother might result in a phallic stage fixation that leads to the boy becoming an aggressive, over-ambitious, and vain man.[26]

Oedipal case study

editIn Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy (1909), the case study of the equinophobic boy "Little Hans", Freud claimed that the relation between Hans's fears—of horses and of his father—derived from external factors, the birth of a sister, and internal factors, the desire of the infantile id to replace his father as companion to his mother, and guilt for enjoying the masturbation normal to a boy of his age. Little Hans himself was unable to relate his fear of horses to his fear of his father. As the treating psychoanalyst, Freud noted that "Hans had to be told many things that he could not say himself" and that "he had to be presented with thoughts, which he had, so far, shown no signs of possessing".[27]

Feminine Oedipus attitude

editFreud applied the Oedipus complex to the psychosexual development of boys and girls, but later modified the female aspects of the theory as "feminine Oedipus attitude" and "negative Oedipus complex".[28] His student–collaborator Carl Jung, in his 1913 work The Theory of Psychoanalysis, proposed the Electra complex to describe a girl's daughter–mother competition for psychosexual possession of the father.[8][29]

In the phallic stage, the feminine Oedipus attitude is the little girl's decisive psychodynamic experience in forming a discrete sexual identity (ego). Whereas a boy develops castration anxiety, a girl develops penis envy, for she perceives that she has been castrated previously (and missing the penis), and so forms resentment towards her own kind as inferior, while simultaneously striving to claim her father's penis through bearing a male child of her own. Furthermore, after the phallic stage, the girl's psychosexual development includes transferring her primary erogenous zone from the infantile clitoris to the adult vagina.[30]

Freud considered a girl's negative Oedipus complex to be more emotionally intense than that of a boy, resulting, potentially, in a woman of submissive, insecure personality.[31]

Freudian theoretic revision

editCarl Gustav Jung

editIn response to Freud's proposal of the Oedipus complex, which was initially more focused on the little boy's experience of desire for the mother and jealous rivalry in relation of the father, student–collaborator Carl Jung proposed that girls experienced desire for the father and aggression towards the mother via what he called the Electra complex.[8] Electra was a Greek mythologic figure who plotted matricidal revenge with Orestes, her brother, against their mother Clytemnestra and their stepfather Aegisthus, for the murder of her father Agamemnon. Like Oedipus, the character is the subject of a play by Sophocles (Electra) from the 5th century BC.[32][33][34] Orthodox Jungian psychology uses the term "Oedipus complex" only to denote a boy's psychosexual development. Freud himself rejected the equivalence, arguing that at this stage of development it is only the male who experiences a simultaneous love for one parent and competitive hatred for the other. For Freud, the idea of the Electra complex assumes an analogous relation between boys and girls, in relation to their same and opposite sex parents, that does not actually exist. According to Freud, the Electra complex fails to take account of the differing effects of the castration complex, and the significance of the phallus, in the two sexes, and overlooks the girl's preoedipal attachment to the mother.[35]

Otto Rank

editIn classical Freudian psychology the super-ego, "the heir to the Oedipus complex", is formed as the infant boy internalizes the familial rules of his father. In contrast, in the early 1920s, using the term "pre-Oedipal", Otto Rank proposed that a boy's powerful mother was the source of the super-ego, in the course of normal psychosexual development. Rank's theoretic conflict with Freud excluded him from the Freudian inner circle; nonetheless, he later developed the psychodynamic Object relations theory in 1925.

Melanie Klein

editWhereas Freud proposed that the father (the paternal phallus) was central to infantile and adult psychosexual development, Melanie Klein concentrated on the early maternal relationship, proposing that Oedipal manifestations are perceptible in the first year of life, the oral stage. Her proposal was part of the "controversial discussions" (1942–44) at the British Psychoanalytical Association. The Kleinian psychologists proposed that "underlying the Oedipus complex, as Freud described it ... there is an earlier layer of more primitive relationships with the Oedipal couple".[36] She assigned "dangerous destructive tendencies not just to the father but also to the mother in her discussion of the child's projective fantasies".[37] Klein's concept of the depressive position, resulting from the infant's ambivalence toward the mother, lessened the central importance of the Oedipus complex in psychosexual development.[38][39]

Wilfred Bion

edit"For the post-Kleinian Bion, the myth of Oedipus concerns investigatory curiosity—the quest for knowledge—rather than sexual difference; the other main character in the Oedipal drama becomes Tiresias (the false hypothesis erected against anxiety about a new theory)".[40] As a result, "Bion regarded the central crime of Oedipus as his insistence on knowing the truth at all costs".[41]

Jacques Lacan

editJacques Lacan argued against removing the Oedipus complex from the center of psychosexual developmental experience. For him, the Oedipus complex "—in so far as we continue to recognize it as covering the whole field of our experience with its signification—may be said to mark the limits that our discipline assigns to subjectivity".[42] It is that which superimposes the kingdom of culture upon the person, marking his or her introduction to the symbolic order.

Thus "a child learns what power independent of itself is as it goes through the Oedipus complex ... encountering the existence of a symbolic system independent of itself".[43] Moreover, Lacan's proposal that "the ternary relation of the Oedipus complex" liberates the "prisoner of the dual relationship" of the son–mother relationship proved useful to later psychoanalysts;[44] thus, for Bollas, the "achievement" of the Oedipus complex is that the "child comes to understand something about the oddity of possessing one's own mind ... discovers the multiplicity of points of view".[45] Likewise, for Ronald Britton, "if the link between the parents perceived in love and hate can be tolerated in the child's mind ... this provides us with a capacity for seeing us in interaction with others, and ... for reflecting on ourselves, whilst being ourselves".[46] As such, in The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (2000), Michael Parsons proposed that such a perspective permits viewing "the Oedipus complex as a life-long developmental challenge ... [with] new kinds of Oedipal configurations that belong to later life".[47]

In 1920, Sigmund Freud wrote that "with the progress of psychoanalytic studies the importance of the Oedipus complex has become, more and more, clearly evident; its recognition has become the shibboleth that distinguishes the adherents of psychoanalysis from its opponents";[48] thereby it remained a theoretic cornerstone of psychoanalysis until about 1930, when psychoanalysts began investigating the pre-Oedipal son–mother relationship within the theory of psychosexual development.[49][50] Janet Malcolm reports that by the late 20th century, to the object relations psychology "avant-garde, the events of the Oedipal period are pallid and inconsequential, in comparison with the cliff-hanging psychodramas of infancy. ... For Kohut, as for Winnicott and Balint, the Oedipus complex is an irrelevance in the treatment of severe pathology".[51] Nonetheless, ego psychology continued to maintain that "the Oedipal period—roughly three-and-a-half to six years—is like Lorenz standing in front of the chick, it is the most formative, significant, moulding experience of human life ... If you take a person's adult life—his love, his work, his hobbies, his ambitions—they all point back to the Oedipus complex".[52]

Criticism

editLack of empirical basis

editStudies conducted of children's attitudes to parents at the oedipal stage do not demonstrate the shifts in positive feelings that are predicted by the theory.[53] Case studies that Freud relied upon, such as the case of Little Hans, could not be verified through research or experimentation on a larger population.[54] Adolf Grünbaum argues that the type of evidence Freud and his followers used, the clinical productions of patients during analytic treatment, by their nature cannot provide cogent observational support for Freud's core hypotheses.[55]

Evolutionary psychologists Martin Daly and Margo Wilson, in their 1988 book Homicide, argue that the Oedipus complex theory yields few testable predictions. They find no evidence of the Oedipus complex in people. There is evidence of parent–child conflict but it is not for sexual possession of the opposite sex-parent.[56]

According to psychiatrist Jeffrey Lieberman, Freud and his followers resisted subjecting his theories, including the Oedipus theory, to scientific testing and verification.[57] Lieberman claims that investigations based in cognitive psychology either contradict or fail to support Freud's ideas.[57]

Cover for sexual abuse

editIn the 1970s, social worker Florence Rush wrote that Freud's seduction theory, which came early in his career, correctly attributed his patients' memories of childhood trauma to the patient's family, often the father, implying that widespread sexual abuse of children by parents was common in his society. According to Rush, the discovery of this abuse made Freud uncomfortable, so he abandoned the theory and invented the Oedipus complex to replace it. The Oedipus complex allowed him to attribute stories of childhood sexual abuse to the children themselves. Freud came to the conclusion that the stories were fantasies of hidden desires, rather than factual descriptions of trauma. Thus, Rush argues, Freud covered up illegal and immoral sexual abuse by undermining the perceptions of his patients, particularly his female patients.[58] Rush's theory became known as The Freudian Coverup.

A director of the Sigmund Freud Archives, Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, adopted the view that Freud's work was a cover-up for abuse after reading Freud's unpublished letters. In his book The Assault on Truth, Masson argues that Freud misattributed accounts of sexual abuse to fabrications and fantasies of children because, for personal reasons, he was unable to accept that the accounts were real. According to Masson, among Freud's reasons to suppress the abuse was that he did not want to be confronted by the father of a patient who was accused of committing abuse. Late in his career Freud sought to prevent colleague Sandor Ferenczi from delivering a paper that reasserted the seduction theory. Freud had hoped that his former student would abandon the theory as he himself had done, but Ferenczi delivered the paper in 1932.[59] Masson writes that, because the theory of the Oedipus complex became widely popular, psychoanalysts continue to do damage to their patients by doubting the reality of the patient's early memories of trauma.

Other Freud scholars argue that Masson and Rush have misrepresented the reasons and intention behind Freud's abandonment of the seduction theory and adoption of the theory of the Oedipus complex. According to Dr. Kurt R. Eissler, who replaced Masson as director of the Freud Archives, Freud did not in any sense reject the reality of childhood sexual trauma, but realized that actual abuse was not the universal cause of neurosis he had thought it to be.[59] New York psychiatrist Dr. Frank R. Hartmann said that "Freud realized he made a mistake in attributing all neurosis to repressed memories of actual abuse. He discovered a much broader theory which explained much more."[59] The historian Peter Gay, author of Freud: A Life for Our Time (1988), emphasizes that Freud continued to believe that some patients were sexually abused, but realized that there can be a difficulty in distinguishing between truth and fiction. Therefore, according to Gay, there was no sinister motive in changing his theory; Freud was a scientist seeking the facts and was entitled to change his views if new evidence was presented to him.[60]

Gender role assumptions

editMany scholars and psychologists observe that, because the theory of the Oedipus complex assigns distinct roles to a mother and father, it is a poor fit for families that do not use traditional gender roles.

As of November 2022 same-sex marriage is legal in 31 nations.[61] Same-sex couples start families through adoption or surrogacy. The pillars of the family structure are diversifying to include parents who are single or of the same sex as their partner along with the traditional heterosexual, married parents. These new family structures pose new questions for the psychoanalytic theories such as the Oedipus complex that require the presence of the mother and the father in the successful development of a child.[37]

Evidence suggests children who have been raised by parents of the same sex are not much different from children raised in a traditional family structure.[37] The classic theory of the Oedipal drama has fallen out of favor in today's society, according to a study by Drescher, having been criticized for its "negative implications" towards same sex parents.[37] Many psychoanalytic thinkers such as Chodorow and Corbett are working towards changing the Oedipus complex to eliminate "automatic associations among sex, gender, and the stereotypical psychological functions deriving from these categories" and make it applicable to today's modern society.[37] From its Freudian conception, psychoanalysis and its theories have always relied on traditional gender roles to draw itself out.

In the 1950s, psychologists distinguished different roles in parenting for the mother and father. The role of primary caregiver is assigned to the mother. Motherly love was considered to be unconditional. While the father is assigned the role of secondary caregiver, fatherly love is conditional, responsive to the child's tangible achievements.[37] The Oedipus complex is compromised in the context of modern family structures, as it requires the existence of the notions of masculinity and femininity.[62] When there is no father present there is no reason for a boy to have castration anxiety and thus resolve the complex.[37] Psychoanalysis presents non-heteronormative relationships a sort of perversion or fetish rather than a natural occurrence.[62] To some psychologists, this emphasis on gender norms can be a distraction in treating homosexual patients.[62]

The 1972 book Anti-Oedipus by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari is "a critique of psychoanalytic normativity and Oedipus" according to Didier Eribon.[63] Eribon criticizes the Oedipus complex described by Freud or Lacan as an "implausible ideological construct" which is an "inferiorization process of homosexuality".[64] According to psychologist Geva Shenkman, "To examine the application of concepts such as Oedipus complex and primal scene to male same-sex families, we must first eliminate the automatic associations among sex, gender, and the stereotypical psychological functions based on these categories."[37]

Postmodern psychoanalytic theories, which aim to reestablish psychoanalysis for modern times, suggest modifying or discarding the complex because it does not describe newer family structures. Shenkman suggests that a loose interpretation of the Oedipus complex in which the child seeks sexual satisfaction from any parent regardless of gender or sex, would be helpful: "From this perspective, any parental authority, or institution for that matter, may represent the taboo that gives rise to the complex". Psychoanalyst Melanie Klein proposed a theory which broke gender stereotypes but still kept traditional father-mother family structure. She assigned "dangerous destructive tendencies not just to the father but also to the mother in her discussion of the child's projective fantasies".[37]

Stretched theory

editAnouchka Grose understands the Oedipus complex as "a way of explaining how human beings are socialised ... learning to deal with disappointment".[65] Her summary of the complex is "You have to stop trying to be everything for your primary carer, and get on with being something for the rest of the world".[66] This post-Lacanian interpretation of the complex diverges considerably from its description in 19th century. Eribon writes that it "stretches the Oedipus complex to a point where it almost doesn't look like Freud's any more".[64]

Aversion to incest

editParent-child and sibling-sibling incestuous unions are almost universally forbidden.[67] An explanation for this incest taboo is that rather than instinctual sexual desire, there is instinctual sexual aversion against these unions (See Westermarck effect). Steven Pinker wrote that "The idea that boys want to sleep with their mothers strikes most men as the silliest thing they have ever heard. Obviously, it did not seem so to Freud, who wrote that as a boy he once had an erotic reaction to watching his mother dressing. Of note is that Amalia Nathansohn Freud was relatively young during Freud's childhood and thus of reproductive age, and Freud having a wet-nurse, may not have experienced the early intimacy that would have tipped off his perceptual system that Mrs. Freud was his mother."[68]

Historical mystique - Ethnocentrism

editBourdieu

editIn Esquisse pour une autoanalyse, Pierre Bourdieu argues that the success of the concept of Oedipus is inseparable from the prestige associated with ancient Greek culture and the relations of domination that are reinforced in the use of this myth. In other words, if Oedipus was Bantu or Baoulé, his story would probably not be viewed as a human universal. This remark recalls the historically and socially situated character of the founder of psychoanalysis.[69]

Malinowski

editSex and Repression in Savage Society is considered "a famous critique of psychoanalysis, arguing that the 'Oedipus complex' described by Freud is not universal."[70]

Sexism

editFeminist views on the Oedipus complex include criticism of the phallocentrism of the theory by philosopher Luce Irigaray among others. Irigaray charges that Freud's work assumes a masculine perspective, epitomized by the centrality of the penis (or lack of a penis for girls) in the Oedipus complex. She thinks that Freud's desire for a neat, symmetrical theory leads him to a contrived understanding of women as inverse men. She charges that he does not explore mother–daughter relationships and that he dogmatically assumes female sexuality will be a perfect mirror of male sexuality.[71]

References

edit- ^ "Oedipus complex". APA Dictionary of Psychology. American Psychological Association. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ a b Nagera, Humberto, ed. (2012) [1969]. "Oedipus complex (pp. 64ff.)". Basic Psychoanalytic Concepts on the Libido Theory. London: Karnac Books. ISBN 978-1-781-81098-9.

- ^ a b Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, Jean-Bertrand (1988) [1973]. "Oedipus complex (pp. 282ff.)". The Language of Psycho-analysis (reprint, revised ed.). London: Karnac Books. ISBN 978-0-946-43949-2.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (1989). Gay, Peter (ed.). The Freud Reader (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 664–665. ISBN 0393026868. OCLC 19125772.

- ^ Auchincloss, Elizabeth (2015). The Psychoanalytic Model of the Mind. American Psychiatric Publishing. p. 110.

- ^ Auchincloss, Elizabeth (2012). Psychoanalytic Terms and Concepts. American Psychoanalytic Association. p. 180.

- ^ a b Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, J.B. (1973). The language of psycho-analysis. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 152. ISBN 0393011054. OCLC 741058.

- ^ a b c Jung, C. G. (1915). The Theory of Psychoanalysis. Nervous and mental disease monograph series, no. 19. New York: Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Co. p. 69.

- ^ Peter Gay (1995) Freud: A Life for Our Time

- ^ Khan, Michael (2002). Basic Freud: Psychoanalytic Thought for the 21st Century. New York, NY: Basic Books. p. 60. ISBN 0-465-03715-1.

- ^ Sigmund Freud The Interpretation of Dreams Chapter V "The Material and Sources of Dreams" (New York: Avon Books) p. 296.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Basic Books. 978-0465019779 (2010) page 282.

- ^ Oedipus as Evidence: The Theatrical Background to Freud's Oedipus Complex Archived 2013-04-18 at the Wayback Machine by Richard Armstrong, 1999

- ^ Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Basic Books. 978-0465019779 (2010) page 247

- ^ Fagles, Robert, "Introduction". Sophocles. The Three Theban Plays. Penguin Classics (1984) ISBN 978-0140444254. page 132

- ^ Dodds, E. R. "On Misunderstanding the Oedipus Rex". The Ancient Concept of Progress. Oxford Press. (1973) ISBN 978-0198143772. page 70

- ^ Birken, Lawrence (Winter 1988). "From Seduction Theory to Oedipus Complex: A Historical Analysis". New German Critique (43): 83–96. doi:10.2307/488399. JSTOR 488399.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund; Masson, J. Moussaieff; Fliess, Wilhelm (1985). The complete letters of Sigmund Freud to Wilhelm Fliess, 1887-1904. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 272. ISBN 9780674154209.

- ^ Bennett Simon, Rachel B. Blass "The development of vicissitudes of Freud's ideas on the Oedipus complex" in The Cambridge Companion to Freud (University of California Press 1991) p.000

- ^ a b Colman, Andrew M. (2014). "Oedipus complex". A Dictionary of Psychology (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199534067.001.0001. ISBN 9780191726828. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund. "A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men" (PDF). Contributions to the Psychology of Love: 170. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ Joseph Childers, Gary Hentzi eds. Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995)

- ^ Charles Rycroft A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (London, 2nd ed., 1995)

- ^ Allan Bullock, Stephen Trombley The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (London:Harper Collins 1999) pp. 607, 705

- ^ Allan Bullock, Stephen Trombley The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought (London:Harper Collins 1999) pp. 205, 107

- ^ Mcleod, Saul (January 16, 2024). "Freud's Psychosexual Theory And 5 Stages Of Human Development". Simply Psychology. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Frank Cioffi (2005) "Sigmund Freud" entry The Oxford Guide to Philosophy Oxford University Press:New York pp. 323–324

- ^ Freud, Sigmund. "Some Psychological Consequences of the Anatomical Distinction between the Sexes" (PDF). questionofexistence.com. International Journal of Psychoanalysis. Retrieved 10 July 2023.

- ^ "Freud, Sigmund (1856-1939)". credoreference.com. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Freud, Sigmund (1989). Gay, Peter (ed.). The Freud Reader (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. pp. 664–665, 674–676. ISBN 0393026868. OCLC 19125772.

- ^ Allan Bullock, Stephen Trombley The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought Harper Collins:London (1999) pp. 259, 705

- ^ Murphy, Bruce (1996). Benét's Reader's Encyclopedia Fourth edition, HarperCollins Publishers:New York p. 310

- ^ Bell, Robert E. (1991) Women of Classical Mythology: A Biographical Dictionary Oxford University Press:California pp.177–78

- ^ Hornblower, S., Spawforth, A. (1998) The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization pp. 254–55

- ^ Laplanche, Jean; Pontalis, J.B. (1974). The Language of Psychoanalysis. New York: Norton. p. 152.

- ^ Richard Appignanesi ed. Introducing Melanie Klein (Cambridge 2006) p. 173

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shenkman, Geva (March 23, 2015). "Classic psychoanalysis and male same-sex parents: A reexamination of basic concepts". Psychoanalytic Psychology. 33 (4): 585–598. doi:10.1037/a0038486.

- ^ Charles Rycroft A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (London, 2nd Edn, 1995)

- ^ Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995)

- ^ Mary Jacobus, The Poetics of Psychoanalysis (London 2005) p. 259

- ^ Michael Parsons The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (London 2000) p. 45

- ^ Jacques Lacan, Ecrits: A Selection (London 1997) p. 66

- ^ Ian Parker, Japan in Analysis (Basingstoke 2008) pp. 82–83

- ^ Jacques Lacan, Ecrits pp. 218, 182

- ^ Adam Phillips On Flirtation (London 1994) p. 159

- ^ Ivan Wood On a Darkling Plain: Journey into the Unconscious (Cambridge 2002) "Ronald Britton" entry p. 118

- ^ Michael Parsons The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (London 2000) p. 4

- ^ Freud, Sexuality pp. 149-50nn

- ^ Charles Rycroft A Critical Dictionary of Psychoanalysis (London, 2nd Ed., 1995)

- ^ Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995) p. 119

- ^ Janet Malcolm, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession (London 1988) pp. 35, 136

- ^ Janet Malcolm, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession (London 1988), "Aaron Green", pp. 158–59 [1]

- ^ Fonagy, Peter; Target, Mary (2006). Psychoanalytic Theories: Perspectives from Developmental Psychopathology. Whurr Publishers. ISBN 9781861562395. OCLC 749483878.

- ^ Wolpe, Joseph; Rachman, Stanley (1960). "Psychoanalytic "evidence": A critique based on Freud's case of little Hans". The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 131 (2): 135–148. doi:10.1097/00005053-196008000-00007. PMID 13786442. S2CID 6276699.

- ^ Carlini, Charles (December 19, 2012). "Testing Freud: Adolf Grünbaum On The Scientific Standing Of Psychoanalysis". Simply Charly.

- ^ Martin Daly, Margo Wilson Homicide (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1988).

- ^ a b The History of Psychiatry (interview with Dr. Jeffrey Lieberman)

- ^ Rush, Florence (1992). The Best-kept Secret Sexual Abuse of Children. Human Services Institute. pp. 83–92. ISBN 9780830639076.

- ^ a b c Blumenthal, Ralph (January 24, 1984). "Freud: secret documents reveal years of strife". The New York Times.

- ^ Gay, Peter (17 June 2006). Freud: A Life for Our Time. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-32861-5.

- ^ Navarre, Brianna. "Same-Sex Marriage Legalization by Country". US News. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Schwartz, David (Winter 1999). "Is a gay Oedipus a Trojan horse? Commentary on Lewes's 'A special Oedipal mechanism in the development of male homosexuality.'". Psychoanalytic Psychology. 16: 88–93. doi:10.1037/0736-9735.16.1.88.

- ^ Didier Eribon, "Échapper à la psychanalyse", Éditions Léo Scheer, 2005, p.14

- ^ a b Didier Eribon, Réflexions sur la question gay, Paris, Fayard, 1999. (ISBN 2213600988), p.129

- ^ Anouchka Grose No More Silly Love Songs (London, 2010) p. 123

- ^ Anouchka Grose No More Silly Love Songs (London, 2010) p. 124

- ^ The Tapestry of Culture An Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, Ninth Edition, Abraham Rosman, Paula G. Rubel, Maxine Weisgrau, 2009, AltaMira Press, page 101

- ^ Pinker, Steven (1997). How the mind works. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393045352. OCLC 36379708.

- ^ Pierre Bourdieu, "Esquisse pour une auto-analyse", raisons d'agir, 2004

- ^ Connell, R. W. (2002). Gender, p. 122. Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-7456-2716-8

- ^ "Psychoanalytic Feminism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. May 16, 2011. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

Further reading

edit- Britton, Ronald. "The missing link: parental sexuality in the Oedipus complex." In The gender conundrum, pp. 91–104. Routledge, 2003.

- Britton, Ronald, Michael Feldman, and Edna O’Shaughnessy. "The Oedipus complex today." London: Karnac (1989).

- Friedman, Richard C., and Jennifer I. Downey. "Biology and the oedipus complex." The Psychoanalytic Quarterly 64, no. 2 (1995): 234–264.

- Green, André. The Tragic Effect: The Oedipus Complex in Tragedy. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

- Klein, Melanie. "The Oedipus complex in the light of early anxieties (1945)." In The Oedipus complex today, pp. 11–82. Routledge, 2018.

- Loewald, Hans W. "The waning of the Oedipus complex." Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 27, no. 4 (1979): 751–775.

- M. Fear, Rhona. The Oedipus Complex: Solutions Or Resolutions?. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2018.

- Parsons, Anne. "Is the Oedipus complex universal." Psychological anthropology: A reader on self in culture 131 (2010).

- Rudnytsky, Peter L.. Freud and Oedipus. United States: Columbia University Press, 1987.

- Ullrich, Burkhard., Zepf, Siegfried., Seel, Dietmar., Zepf, Florian Daniel. Oedipus and the Oedipus Complex: A Revision. N.p.: Taylor & Francis, 2018.

- Simon, Bennett. "“Incest—see under oedipus complex”: The history of an error in psychoanalysis." Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 40, no. 4 (1992): 955-988.

- Smadja, Éric. The Oedipus Complex: Focus of the Psychoanalysis-Anthropology Debate. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis, 2017.

- The Oedipus Complex - A Selection of Classic Articles on Sigmund Freud's Psychoanalytical Theory. N.p.: Read Books, 2011.

- Weissberg, Liliane (ed.), Psychoanalysis, Fatherhood, and the Modern Family. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Günter Rebing: "Aber so arbeitet nun einmal das Genie". Wie der Ödipuskomplex erfunden wurde. In: Sinn und Form 73 (2021), Heft 6, pp. 837–843