Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (formerly Ocmulgee National Monument) in Macon, Georgia, United States preserves traces of over ten millennia of culture from the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. Its chief remains are major earthworks built before 1000 CE by the South Appalachian Mississippian culture (a regional variation of the Mississippian culture.)[4] These include the Great Temple and other ceremonial mounds, a burial mound, and defensive trenches. They represented highly skilled engineering techniques and soil knowledge, and the organization of many laborers. The site has evidence of "12,000 years of continuous human habitation."[5] The 3,336-acre (13.50 km2) park is located on the east bank of the Ocmulgee River. Macon, Georgia developed around the site after the United States built Fort Benjamin Hawkins nearby in 1806 to support trading with Native Americans.

| Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

The Great Temple Mound (right) and the Lesser Mound (left) | |

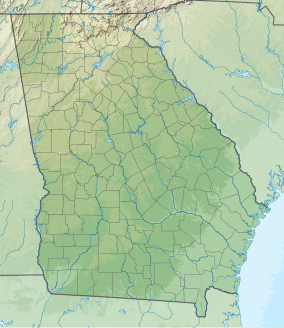

| Location | Macon, Georgia, USA |

| Coordinates | 32°50′12″N 83°36′30″W / 32.83667°N 83.60833°W |

| Area | 3,336 acres (13.50 km2)[1] |

| Established | December 23, 1936 |

| Visitors | 122,722 (in 2011)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000099[3] |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

For thousands of years, succeeding cultures of prehistoric indigenous peoples had settled on what is called the Macon Plateau at the Fall Line, where the rolling hills of the Piedmont met the Atlantic coastal plain. The monument designation included the Lamar Mounds and Village Site, located downriver about three miles (4.8 km) from Macon. The site was designated for federal protection by the National Park Service (NPS) in 1934, listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and redesignated in 2019 as a national historical park.

History

editMacon Plateau culture

editOcmulgee (/oʊkˈmʌlɡiː/) is a memorial to ancient indigenous peoples in Southeastern North America. The name comes from the Mikasuki Oki Molki, meaning 'Bubbling Water'.[6] From Ice Age hunters to the Muscogee Creek tribe of historic times, the site has evidence of 12,000 years of human habitation. The Macon plateau was inhabited during the Paleoindian, Archaic, and Woodland phases.

The major occupation was ca. 950–1150 CE during the Early Mississippian-culture phase. The people of this sophisticated, stratified culture built the complex, massive earthworks that expressed their religious and political system.[7] Archeologists call this society the Macon Plateau culture, a local expression of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture.[8] During this period, an elite society supported by skillful farmers developed a town. Leaders directed the complex construction of large, earthwork platform mounds, the central structures on the plateau.

Carrying earth by hand in bags, thousands of workers built the 55 ft (17 m)-high Great Temple Mound on a high bluff overlooking the floodplain of the Ocmulgee River. Magnetometer scans have revealed the platform mound had a spiraling staircase oriented toward the floodplain. The staircase is unique among any of the Mississippian-culture sites. Other earthworks include at least one burial mound.

The people built rectangular wooden buildings to house certain religious ceremonies on the top of the platform mounds. The mounds at Ocmulgee were unusual because they were constructed further from each other than was typical of other Mississippian complexes. Scholars believe this was to provide for public space and residences around the mounds.

Circular earth lodges were built to serve as places to conduct meetings and important ceremonies. Remains of one of the earth lodges were carbon dated to 1050 CE. This evidence was the basis for the reconstructed lodge which archeologists later built at the park center. The interior features a raised-earth platform, shaped like an eagle with a forked-eye motif. Molded seats on the platform were built for the leaders. The eagle was a symbol of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex, which the people shared with other Mississippian cultures.

Lamar Period

editAs the Mississippian culture declined at the ceremonial center, ca. 1350 a new culture coalesced among people who lived in the swamps downstream. The Late Mississippian period (1350–1600 CE),[9] also consisted of the Lamar Period, where natives built two mounds that have survived at that site, including a unique spiral mound. The Lamar period is composed of four distinct phases that lasted between the years 1375 and 1670. It is identified through unique ceramic design elements that were primarily produced during this period.[10] These four phases were the Duvall, Iron Horse, Dyar, and Bell phases.[10]

The people at Lamar had a village associated with the mounds. They protected it by a constructed defensive palisade of logs placed vertically. They built rectangular houses, with roofs made of thatch or sod and clay-plastered walls, which were located around the mounds.[11] This archeological site of a former settlement is now protected as the Lamar Mounds and Village Site.[12]

Lamar pottery was distinctive, stamped with complex designs like the pottery of the earlier Woodland peoples. It was unlike other pottery of the Macon Plateau culture. Many archaeologists believe the Lamar culture was related to the earlier Woodland inhabitants, who, after being displaced by the newer Mississippian culture migrants, developed a hybrid culture.[13] Late Woodland Period characteristics extended into the Mississippian Period of 800–1600 CE.[13]

Spanish contact

editIn 1540, the expedition of Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto recorded its travel through the chiefdom of Ichisi. Historians and archeologists believe this was likely what is now known as the Lamar site.[14] The Spaniards left a trail of destruction in their wake as they explored the present-day Southeastern U.S.[citation needed] in a failed search for precious metals. Their deadliest legacy of unintended consequences was likely related to the pigs they brought as food supply. Escaping pigs became feral, disrupting local habitat and spreading Eurasian infectious diseases. As the American Indians had no acquired immunity to these new diseases, they suffered high fatalities. The rate of deaths caused social dislocations and likely contributed to a collapse of the Mississippian cultures.[15]

In the aftermath of De Soto's expedition, the Mississippian cultures declined and disappeared. Hierarchical chiefdoms crumbled. They were replaced by loose confederacies of clans and the rise of historic regional tribes. The clans did not produce the agricultural surpluses of the previous society, which had supported the former population density and development of complex culture. Agriculture had enabled the development of hierarchy in the larger population. Its leaders planned and directed the corvée labor system that raised and maintained the great earthen mounds. The culture supported artisans as well.

Muscogee in the colonial era

editBy the late 18th century, the largest Native American confederacy in present-day Georgia and Alabama was the Muscogee confederacy (known during the colonial and federal periods as the Muscogee Creek tribe). They were among the Muskogean-speaking peoples of the Southeast.

They considered the ancient Mississippian mounds at Ocmulgee to be sacred and made pilgrimages there. According to Muscogee oral tradition, the mounds area was "the place where we first sat down", after their ancestors ended their migration journey from the West.[16]

In 1690, Scottish fur traders from Carolina built a trading post on Ochese Creek (Ocmulgee River), near the Macon Plateau mounds. Some Muscogee settled nearby, developing a village along the Ocmulgee River near the post, where they could easily acquire trade goods. They defied efforts by Spanish Florida authorities to bring them into the mission province of Apalachee.[17]

The traders referred to both the river and the peoples living along it as "Ochese Creek." Later usage shortened the term to Creek, which traders and colonists applied to all Muskogean-speaking peoples.[17] The Muscogee called their village near the trading-post Ocmulgee (bubbling waters) in the local Hitchiti language. Carolina European colonists called it Ocmulgee Town, and later named the river after it. .

The Muscogee traded pelts of white tailed deer and Native American slaves captured in traditional raids against other tribes. They received West Indian rum, European cloth, glass beads, hatchets, swords, and flintlock rifles from the colonial traders. Carolinian fur traders, who were men of capital, took Muscogee wives, often the daughters of chiefs. It was a practice common also among European fur traders in Canada; both the fur traders and Aboriginal Canadians saw such marriages as a way to increase the alliances among the elite of both cultures. The fur traders encouraged the Muscogee slaving raids against Spanish "Mission Indians." The English and Scots colonists were so few in number in the Carolina region that they depended on Native American alliances for security and survival.

In 1702, Carolina governor James Moore raised a militia of 50 colonists and 1,000 Yamasee and Ochese Creek warriors. From 1704 to 1706, they attacked and destroyed a significant number of Spanish missions in coastal Georgia and Florida. They captured numerous Indians who were referred to as Mission tribes: the Timucua and Apalachee. The colonists and some of their Indian allies sold their captives into slavery, with many being transported to Caribbean plantations. Together with extensive fatalities from epidemics of infectious diseases, the warfare caused Florida's indigenous population to fall from about 16,000 in 1685 to 3,700 by 1715.[18]

As Florida was depopulated, the English-allied tribes grew indebted to slave traders in Carolina. They paid other tribes to attack and enslave Native Americans, raids that were a catalyst for the Yamasee War in 1715. In an effort to drive the colonists out, the Ochese Creek joined the rebellion and burned the Ocmulgee trading post. In retaliation, the South Carolina authorities began arming the Cherokee, whose attacks forced the Ochese Creek to abandon the Ocmulgee and Oconee rivers, and move west to the Chattahoochee River. The Yamasee took refuge in Spanish Florida.

After the defeat of the Yamasee, former soldier James Oglethorpe established the colony of Georgia, founding the settlement of Savannah on the coast in 1733. Although various development schemes were attempted (silkworm cultivation, production of naval stores), the colony did not become profitable until after Georgia ended its prohibition of slavery. The founders had intended to provide a colony for hardworking yeomen laborers, but not enough people were willing to immigrate from England and bear its hard conditions. The colony began to import enslaved Africans as laborers and to develop the labor-intensive rice, cotton and indigo plantations in the 1750s in the Low Country and on the Sea Islands. These commodity crops, based on slave labor, generated the wealth of the planter class of Georgia and South Carolina.

Because of continuing conflicts with European colonists and other Muscogee groups, many Ochese Creek migrated from Georgia to Spanish Florida in the later 18th century. There they joined with earlier refugees of the Yamasee War, remnants of Mission Indians, and fugitive slaves, to form a new tribe which became known as the Seminole. They spoke mostly Muscogee.

Relations with the United States

editThe Ocmulgee mounds evoked awe in eighteenth-century travelers. The naturalist William Bartram journeyed through Ocmulgee in 1774 and 1776. He described the "wonderful remains of the power and grandeur of the ancients in this part of America."[19] Bartram was the first to record the Muscogee oral histories of the mounds' origins.

The Lower Creek of Georgia initially had good relations with the federal government of the United States, based on the diplomacy of both Benjamin Hawkins, President George Washington's Indian agent, and the Muscogee Principal Chief Alexander McGillivray. McGillivray was the son of Sehoy II, a Muscogee woman of the Wind Clan, and Lachlan McGillivray, a wealthy Scottish fur trader. He achieved influence both within the matrilineal tribe, because of the status of his mother's family, and among the Americans, because of his father's position and wealth. McGillivray secured U.S. recognition of Muscogee and Seminole sovereignty by the Treaty of New York (1790).

But, after the invention of the cotton gin in 1794 made cultivation of short-staple cotton more profitable, Georgians were eager to acquire Muscogee corn fields of the uplands area to develop as cotton plantations; they began to encroach on the native territory. Short-staple cotton could be grown here, whereas Low Country plantations had to use long-staple cotton.

Under government pressure in 1805, the Lower Creek ceded their lands east of the Ocmulgee River to the state of Georgia, but they refused to surrender the sacred mounds. They retained a 3-by-5-mile (4.8 km × 8.0 km) area on the east bank called the Ocmulgee Old Fields Reserve. It included both the mounds on the Macon Plateau and the Lamar mounds.

In 1806 the Jefferson administration ordered Fort Benjamin Hawkins to be built on a hill overlooking the mounds. The fort was of national and state military importance through 1821, used as a US Army command headquarters, and a supply depot for campaigns in the War of 1812 and later. Economically, it was important as a trading post, or United States factory, to regulate the Creek Nation's trade in deerskins. In addition, it served as a headquarters and mustering area for the Georgia state militia. It served as a point of contact among the Creek Nation, the US, and the state of Georgia military and political representatives.[20]

Tensions among the Upper Creek and Lower Creek towns increased with encroachment by European-American settlers in Georgia. Many among the Upper Creek wanted to revive traditional culture and religion, and a young group of men, the Red Sticks, formed around their prophets. The US and Georgia forces used the fort as a base during the Creek War of 1813–1814. At the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814, General Andrew Jackson defeated the Red Stick faction of the Upper Creek. Together with their own issues, the Red Sticks had been influenced by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and were seeking to drive the Americans out of their territory. The Lower Creek fought alongside the U.S. against the Red Sticks.

Led by Chief William McIntosh, the Lower Creek also allied with the United States in the First Seminole War in Florida. McIntosh's influence in the area was extended by his family ties to Georgia's planter elite through his wealthy Scots father of the same name. McIntosh was also connected to the McGillivray clan. A resident of Savannah, the senior McIntosh had strong ties to the British and had served as a Loyalist officer during the American Revolution. He tried to recruit the Lower Creek to fight for the British in the war. Remaining in the new United States after the war, he became a cotton planter.

In 1819, the Lower Creek gathered for the last time at Ocmulgee Old Fields. In 1821, Chief McIntosh agreed to the first Treaty of Indian Springs, by which the Lower Creek ceded their lands east of the Flint River, including Ocmulgee Old Fields, to the United States. In 1822 the state chartered Bibb County, and the following year the town of Macon was founded.

The Creek National Council struggled to end such land cessions by making them a capital offense. But in 1825, Chief McIntosh and his paternal cousin, Georgia Governor George Troup, negotiated an agreement with the US. McIntosh and several other Lower Creek chiefs signed the second Treaty of Indian Springs in 1825. McIntosh ceded the remaining Lower Creek lands to the United States, and the Senate ratified the treaty by one vote, despite its lacking the signature of Muscogee Principal Chief William McIntosh. Soon after that, the chief Menama and 200 warriors attacked McIntosh's plantation. They killed him and burned down his mansion in retaliation for his alienating the communal lands.

William McIntosh and a Muscogee delegation from the National Council went to Washington to protest the treaty to President John Quincy Adams. The US government and the Creek negotiated a new treaty, called the Treaty of New York (1826), but the Georgia state government proceeded with evicting Creek from lands under the 1825 treaty. It also passed laws dissolving tribal government and regulating residency on American Indian lands.

In 1828, Andrew Jackson was elected president. He supported Indian removal, signing legislation to that effect by Congress in 1830. Later he used US Army forces to remove the remnants of the Southeastern Indian tribes through the 1830s. The Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and most of the Seminole, known as the Five Civilized Tribes, were all removed from the Southeast to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Following Indian Removal, the Muscogee reorganized in the Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). In 1867 they founded a new capital, which they called Okmulgee in honor of their sacred mounds on the plateau of the Georgia fall line.[21]

National Historical Park

editDesignations

editWhile the mounds had been studied by some travelers, professional excavation under the evolving techniques of archeology did not begin until the 1930s, under the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt during the Great Depression. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) sponsored large-scale archaeological digs at the site between 1933 and 1942. Workers excavated portions of eight mounds, finding an array of significant archeological artifacts that revealed a wide trading network and complex, sophisticated culture.[22] On June 14, 1934, the park was authorized by Congress as a national monument and formally established on December 23, 1936, under the National Park Service.

As an historic unit of the Park Service, the national monument was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. In 1997, the NPS designated Ocmulgee Old Fields as a Traditional Cultural Property, the first such site named east of the Mississippi River.

The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act, signed March 12, 2019, redesignated it as a national historical park and increased its size by about 2,100 acres.[23] It has an NPS-owned area of 701 acres (2.84 km2). The expanded area will be conveyed to the Park Service following redevelopment.[24] 906 acres were transferred to the park on February 9, 2022, after negotiations headed by the Open Space Institute halted incompatible industrial development adjacent to the park; under the same deal, an additional 45 acres were transferred to the Ocmulgee Land Trust while wetlands restoration occurs, and will be transferred to the park at a later date.[25]

Facilities

editOcmulgee's visitor center includes an archaeology museum. It displays artifacts and interprets the successive cultures of the prehistoric Native Americans who inhabited this site for thousands of years. In addition, it interprets the historic Muscogee Creek tribe and the their diverse tribal towns who settled this region archaeologically and historically during the colonial era. The visitor center includes a short orientation film for the site. Its gift shop has a variety of craft goods, and books related to the park. In the early 1990s, the National Park Service renovated its facilities at the park.

The large park encompasses 702 acres (2.84 km2), and has 5+1⁄2 miles (8.9 km) of walking trails. Near the visitor center is a reconstructed ceremonial earthlodge, based on a 1,000-year-old structure excavated by archeologists. Visitors can reach the Great Temple Mound via a half-mile walk or the park road. Other surviving prehistoric features in the park include a burial mound, platform mounds, and earthwork trenches. The historic site of the English colonial trading post at Ocumulgee, when they were allied with the Muscogee, is also part of the park. It was discovered during archeological excavations in the 1930s.

The main section of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park is accessible from U.S. Route 80, off Interstate 16 (which passes through the southwest edge of the park). It is open daily except Christmas Day and New Year's Day.

The Lamar Mounds and Village Site is an isolated unit of the park, located in the swamps about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Macon. The Lamar Site is open on a limited basis.

Potential expansion and redesignation as a national park and preserve

editIn 2022, the NPS conducted a Special Resource Study on the Ocmulgee River Corridor,[26] which could have recommended expansion of the area as a national park and preserve.[27][28] The study area includes parts of Bond Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, Robins Air Force Base, and three Georgia state wildlife management areas.[29] The Muscogee Nation may be a partner in conservation management.[30]

In November 2023, the study's findings, which were sent to Congress, concluded that the Corridor proposal was unfeasible at the time due to estimated costs of acquisition, as well as opposition from landowners and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, but also assessed the Corridor as meeting criteria for "national significance and suitability" and recommended a scaled-down plan covering less land and operating as a public-private partnership (such as a National Heritage Area or National Historic Landmark designation) in association with the Muscogee Nation and other stakeholders.[31] Despite the study's findings and recommendations, Senators Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock and Representatives Sanford Bishop and Austin Scott, whose districts covered the Ocmulgee River watershed in question, announced their intent to support the intended expansion.[32][33]

Images

edit-

park entrance sign

-

Looking upward to the Great Temple Mound from the bluff above the Ocmulgee River

-

view from top of Great Temple Mound

-

The Great Temple Mound

-

Gator Sign at Ocmulgee Mounds National Historic Park

-

map on display at Fort Hawkins

Archaeology Museum

edit-

Pipes, necklaces, and a pottery vessel with a lid the shape of a human head, found at Ocmulgee

-

Col. James Moore's raiding party passes the Ocmulgee trading-post

-

Earth Lodge Display

-

detail of museum

Ocmulgee Earth Lodge

edit-

entrance to earth lodge

-

interior of earth lodge

-

interior of earth lodge

-

Earthlodge fireplace. Nearby were 47 molded seats where the high chiefs or priests sat on the eagle platform

Further reading

edit- Jennings, Matthew and Gordon Johnston. 2017. Ocmulgee National Monument. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Listing of acreage – December 31, 2020" (XLSX). Land Resource Division, National Park Service. (National Park Service Acreage Reports)

- ^ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved May 14, 2012.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ "Southeastern Prehistory:Mississippian and Late Prehistoric Period". National Park Service. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ^ "Ocmulgee National Monument", National Park Service, accessed 15 July 2011

- ^ "Ocmulgee". The River Basin Center. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ David J. Holly, "Macon Plateau", in Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia, p. 601

- ^ "Macons Mississippians". Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ "Timeline: Archaeological Periods". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Rogers, J. Daniel; Smith, Bruce D. (1995). Mississippian Communities and Households. University of Alabama Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780817384227.

- ^ Macon, Mailing Address: 1207 Emery Hwy; Us, GA 31217 Phone:752-8257 x222 Contact. "History & Culture - Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved July 24, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Ocmulgee National Monument", National Park Service

- ^ a b Pluckhahn, Thomas (February 19, 2003). "Woodland Period: Overview". New Georgia Encyclopedia.

- ^ "Hernando de Soto", National Park Service

- ^ Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations on the Americas Before Columbus, 2005, pp. 107-110

- ^ "Sacred Sites International Foundation - Ocmulgee Old Fields". Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- ^ a b "Notice of Inventory Completion for Native American Human Remains and Associated Funerary Objects ... Ocmulgee National Monument,", Federal Register Notice, National Park Service

- ^ Alan Taylor, American Colonies: The Settling of North America, New York: Penguin Books: 2001, p. 233

- ^ "Ocmulgee National Monument", Colonial History, National Park Service

- ^ Daniel T. Elliott, Fort Hawkins: 2005-2007 Field Seasons Archived 2011-10-01 at the Wayback Machine, The LAMAR Institute, Report 124, 2008, p. 1, accessed 16 July 2011

- ^ "Muscogee" Archived 2010-03-12 at the Wayback Machine, Oklahoma History and Culture

- ^ David Holly, "Macon Plateau", in Guy E. Gibbon, Ed., Archaeology of Prehistoric Native America: An Encyclopedia, New York: Routledge, 1998, p. 601

- ^ "Text - S.47 - John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act". United States Congress. March 12, 2019. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ Gambill, Rachel. "House demolitions part of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park expansion | Macon-Bibb County, Georgia". Retrieved March 22, 2021.

- ^ Macon, Mailing Address: 1207 Emery Hwy; Us, GA 31217 Phone: 478 752-8257 x222 Contact. "Acquisition More than Doubles the Size of Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park - Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "ParkPlanning - Ocmulgee River Corridor SRS". parkplanning.nps.gov. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Hall, Mary Helene. "Macon's Ocmulgee Mounds expected to become National Park, but roadblocks remain". Georgia Public Broadcasting. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Woods, Mark. "An old park in the middle of Georgia worthy of becoming new national park | Mark Woods". The Florida Times-Union. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ "Ocmulgee National Park & Preserve Initiative". Georgia Conservancy.

- ^ "The Muscogee get their say in national park plan for Georgia". Georgia Public Broadcasting. Associated Press. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ "National Park Service completes Special Resource Study for Ocmulgee River Corridor in Central Georgia - Office of Communications (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ "BISHOP, OSSOFF, WARNOCK, AND AUSTIN SCOTT ON LATEST OCMULGEE MOUNDS DEVELOPMENT | Congressman Sanford Bishop". bishop.house.gov. November 17, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ "National Park Service delivers roadmap for protecting Georgia's Ocmulgee River corridor". AP News. November 16, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- The National Parks: Index 2001–2003. Washington: U.S. Department of the Interior.

External links

edit- Official NPS website: Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park

- Virtual Tour of Ocmulgee

- Ocmulgee National Monument: 3 Mile Hiking Loop

- "Ocmulgee Mounds", New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Lamar Mounds coordinates: 32°48′45″N 83°35′34″W / 32.81250°N 83.59278°W

- Geographic data related to Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park at OpenStreetMap