Northamptonshire (/nɔːrˈθæmptənʃər, -ʃɪər/ nor-THAMP-tən-shər, -sheer;[4][5] abbreviated Northants.) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Leicestershire, Rutland and Lincolnshire to the north, Cambridgeshire to the east, Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire to the south and Warwickshire to the west. Northampton is the largest settlement and the county town.

Northamptonshire

Northants | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 52°18′N 0°48′W / 52.300°N 0.800°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Constituent country | England |

| Region | East Midlands |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| UK Parliament | 7 MPs |

| Police | Northamptonshire Police |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Lord Lieutenant | James Saunders Watson[1] |

| High Sheriff | Amy Louise Crawfurd[2] (2024/25) |

| Area | 2,364 km2 (913 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 24th of 48 |

| Population (2022)[3] | 792,421 |

| • Rank | 31st of 48 |

| Density | 335/km2 (870/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity |

|

| Unitary authorities | |

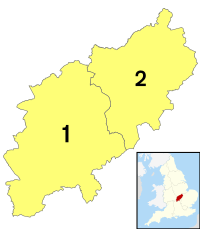

| Councils | West Northamptonshire Council North Northamptonshire Council |

| Districts | |

Districts of Northamptonshire Unitary: | |

The county has an area of 2,364 km2 (913 sq mi) and a population of 747,622. The latter is concentrated in the centre of the county, which contains the county's largest towns: Northampton (249,093), Corby (75,571), Kettering (63,150), and Wellingborough (56,564).[citation needed] The northeast and southwest are rural. The county contains two local government districts, North Northamptonshire and West Northamptonshire, which are both unitary authority areas. The historic county included the Soke of Peterborough.

The county is characterised by low, undulating hills, particularly to the west. They are the source of several rivers, including the Avon and Welland, which form much of the northern border; the Cherwell; and the Great Ouse. The River Nene is the principal river within the county, having its source in the southwest and flowing northeast past Northampton and Wellingborough. The highest point is Arbury Hill southwest of Daventry, at 225 m (738 ft).

There are Iron Age and Roman remains in the county, and in the seventh century it was settled by the Angles and Saxons, becoming part of Mercia. The county likely has its origin in the Danelaw as the area controlled from Northampton, which was one of the Five Boroughs. In the later Middle Ages and Early Modern Period the county was relatively settled, although Northampton was the location of engagements during the First and Second Barons' Wars and the Wars of the Roses, and during the First English Civil War Naseby was the site of a decisive battle which destroyed the main Royalist army. During the Industrial Revolution Northamptonshire became known for its footwear, and the contemporary county has a number of small industrial centres which specialise in engineering and food processing.[6][7]

History

editMuch of Northamptonshire's countryside appears to have remained somewhat intractable as regards early human occupation, resulting in an apparently sparse population and relatively few finds from the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic and Neolithic periods.[8] In about 500 BC the Iron Age was introduced into the area by a continental people in the form of the Hallstatt culture,[9] and over the next century a series of hill-forts were constructed at Arbury Camp, Rainsborough camp, Borough Hill, Castle Dykes, Guilsborough, Irthlingborough, and most notably of all, Hunsbury Hill. There are two more possible hill-forts at Arbury Hill (Badby) and Thenford.[9]

In the 1st century BC, most of what later became Northamptonshire became part of the territory of the Catuvellauni, a Belgic tribe, the Northamptonshire area forming their most northerly possession.[9] The Catuvellauni were in turn conquered by the Romans in 43 AD.[10]

The Roman road of Watling Street passed through the county, and an important Roman settlement, Lactodurum, stood on the site of modern-day Towcester. There were other Roman settlements at Northampton, Kettering and along the Nene Valley near Raunds. A large fort was built at Longthorpe.[9]

After the Romans left, the area eventually became part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia, and Northampton functioned as an administrative centre. The Mercians converted to Christianity in 654 AD with the death of the pagan king Penda.[11] From about 889 the area was conquered by the Danes (as at one point almost all of England was, except for Athelney marsh in Somerset) and became part of the Danelaw – with Watling Street serving as the boundary – until being recaptured by the English under the Wessex king Edward the Elder, son of Alfred the Great, in 917. Northamptonshire was conquered again in 940, this time by the Vikings of York, who devastated the area, only for the county to be retaken by the English in 942.[12] Consequently, it is one of the few counties in England to have both Saxon and Danish town-names and settlements.[citation needed]

The county was first recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (1011), as Hamtunscire: the scire (shire) of Hamtun (the homestead). The "North" was added to distinguish Northampton from the other important Hamtun further south: Southampton – though the origins of the two names are in fact different.[13]

Rockingham Castle was built for William the Conqueror[14] and was used as a Royal fortress until Elizabethan times. In 1460, during the Wars of the Roses, the Battle of Northampton took place and King Henry VI was captured.[15] The now-ruined Fotheringhay Castle was used to imprison Mary, Queen of Scots, before her execution.[16]

During the English Civil War, Northamptonshire strongly supported the Parliamentarian cause, and the Royalist forces suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Naseby in 1645 in the north of the county. King Charles I was imprisoned at Holdenby House in 1647.[17]

George Washington, the first President of the United States of America, was born into the Washington family who had migrated to America from Northamptonshire in 1656. George Washington's ancestor, Lawrence Washington, was Mayor of Northampton on several occasions and it was he who bought Sulgrave Manor from Henry VIII in 1539. It was George Washington's great-grandfather, John Washington, who emigrated in 1656 from Northamptonshire to Virginia. Before Washington's ancestors moved to Sulgrave, they lived in Warton, Lancashire.[18]

In the 18th and 19th centuries, parts of Northamptonshire and the surrounding area became industrialised. The local specialisation was shoemaking and the leather industry and became one of Britain's major centres for these crafts by the 19th century. In the north of the county a large ironstone quarrying industry developed from 1850.[19]

In 1823 Northamptonshire was said to "[enjoy] a very pure and wholesome air" because of its dryness and distance from the sea. Its livestock were celebrated: "Horned cattle, and other animals, are fed to extraordinary sizes: and many horses of the large black breed are reared."[20]

Nine years later, the county was described as "a county enjoying the reputation of being one of the healthiest and pleasantest parts of England" although the towns were "of small importance" with the exceptions of Peterborough and Northampton. In summer, the county hosted "a great number of wealthy families... country seats and villas are to be seen at every step."[21] Northamptonshire is still referred to as the county of "spires and squires" because of the numbers of stately homes and ancient churches.[22]

Prior to 1901 the ancient hundreds were disused. Northamptonshire was administered as four major divisions: Northern, Eastern, Mid, and Southern.[23] During the 1930s, the town of Corby was established as a major centre of the steel industry. Much of Northamptonshire nevertheless remains rural.[citation needed]

Corby was designated a new town in 1950[24] and Northampton followed in 1968.[25] As of 2005[update] the government is encouraging development in the South Midlands area, including Northamptonshire.[26]

Peterborough

editThe city and Soke of Peterborough were part of the historic county of Northamptonshire; from the time that formal county boundaries were established by the Normans in the 11th century, to 1965. The Church of England Diocese of Peterborough that covers Northamptonshire is still centred at Peterborough Cathedral.[27] The city of Peterborough had its own courts of quarter sessions and, later, the Soke had its own county council, making it an autonomous district of Northamptonshire.

In 1965, the ancient Soke of Peterborough was abolished by the Local Government Boundary Commission; the city of Peterborough and the surrounding villages that were previously part of the Soke, were transferred to the newly created county of Huntingdon and Peterborough.[28]

The new county of Huntingdon and Peterborough was short lived; it was abolished in 1974. Upon its abolishment, the city of Peterborough and the other settlements that were once part of the former Soke, were transferred to the county of Cambridgeshire, instead of being transferred back to Northamptonshire. Additionally, the former historical county of Huntingdonshire, which had been abolished along with the Soke of Peterborough in 1965 to create the County of Huntingdon and Peterborough, was not reinstated as a Shire county in its own right in 1974. Instead, Huntingdonshire was transferred to and became a district of Cambridgeshire.

Since 1965, Northamptonshire has been one of the small number of English counties that does not contain a city.

Little Bowden

editIn 1879, a local government district was created covering the three parishes of Market Harborough and Great Bowden and Little Bowden.[29] When elected county councils were established in 1889, local government districts were placed entirely in one county, and thus the parish of Little Bowden, a neighbourhood of Market Harborough, was transferred from Northamptonshire to Leicestershire.[30]

Stamford

editUntil 1832 and 1835, Stamford Baron St Martin which forms the southern part of the town of Stamford in Lincolnshire was part of Northamptonshire as St Martin Without. It was later incorporated into the then Municipal Borough of Stamford under the then Parts of Kesteven.[31]

Geography

editNorthamptonshire is a landlocked county in the southern part of the East Midlands,[32] sometimes known as the South Midlands. The county contains the watershed between the River Severn and The Wash, and several important rivers have their sources in the north-west of the county, including the River Nene, which flows north-eastwards to The Wash, and the Warwickshire Avon, which flows south-west to the Severn. In 1830, it was boasted that "not a single brook, however insignificant, flows into it from any other district".[33] In the west of the county, the hills most commonly referred to as the Northamptonshire Uplands can be found, in this area, the highest point in the county, Arbury Hill, at 225 metres (738 ft), can be found, just to the south of Daventry.[34][35] The boundary with Lincolnshire is England's shortest ceremonial county boundary, at 20 yards (18 metres).[36]

There are several towns in the county, Northampton being the largest and most populous. At the time of the 2011 census a population of 691,952 lived in the county, with 212,069 living in Northampton. The table below shows all towns with over 10,000 inhabitants.

| Rank | Town | Population | Former Borough/District council |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Northampton | 249,093 (2021) | Northampton Borough Council |

| 2 | Corby | 75,571 (2021) | Corby Borough Council |

| 3 | Kettering | 63,150 (2021) | Kettering Borough Council |

| 4 | Wellingborough | 56,564 (2021) | Borough Council of Wellingborough |

| 5 | Rushden | 31,690 (2021) | East Northamptonshire District Council |

| 6 | Daventry | 28,123 (2021) | Daventry District Council |

| 7 | Brackley | 16,159 (2021) | South Northamptonshire District Council |

| 8 | Towcester | 11,524 (2021) | South Northamptonshire District Council |

As of 2010 there were 16 settlements in Northamptonshire with a town charter:

- Brackley, Burton Latimer, Corby, Daventry, Desborough, Higham Ferrers, Irthlingborough, Kettering, Northampton, Oundle, Raunds, Rothwell, Rushden, Towcester, Thrapston and Wellingborough.

Climate

editLike the rest of the British Isles, Northamptonshire has an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification). The table below shows the average weather for Northamptonshire from the Moulton weather station.

| Climate data for Moulton, Northants | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7 (45) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

19 (66) |

14 (57) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

14 (58) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

2 (36) |

4 (39) |

4 (39) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

10 (50) |

8 (46) |

5 (41) |

3 (37) |

7 (44) |

| Average precipitation cm (inches) | 4.51 (1.78) |

3.39 (1.33) |

2.87 (1.13) |

4.39 (1.73) |

3.49 (1.37) |

4.66 (1.83) |

4.21 (1.66) |

4.69 (1.85) |

5.49 (2.16) |

5.68 (2.24) |

4.8 (1.9) |

4.98 (1.96) |

53.16 (20.94) |

| Source: [37] | |||||||||||||

Governance

editLocal government

editBetween 1974 and 2021, Northamptonshire, like most English counties, was divided into a number of local authorities. The seven borough/district councils covered 15 towns and hundreds of villages. The county had a two-tier structure of local government and an elected county council based in Northampton, and was also divided into seven districts each with their own district or borough councils:[38]

Northampton itself is the most populous civil parish in England, and (prior to 2021) was the most populous urban district in England not to be administered as a unitary authority (even though several smaller districts are unitary). During the 1990s local government reform, Northampton Borough Council petitioned strongly for unitary status, which led to fractured relations with the County Council.[citation needed]

The Soke of Peterborough is within the historic county of Northamptonshire, although it had had a separate county council since 1889 and separate courts of quarter sessions before then. The city of Peterborough has been a unitary authority since 1998, but it forms part of Cambridgeshire for ceremonial purposes.[39]

De facto bankruptcy of the county council

editIn early 2018, Northamptonshire County Council was declared technically insolvent and would be able to provide only the bare essential services.[40] According to The Guardian the problems were caused by "a reckless half-decade in which it refused to raise council tax to pay for the soaring costs of social care" and "partly due to past failings, the council is now having to make some drastic decisions to reduce services to a core offer." Some observers, such as Simon Edwards of the County Councils Network, added another perspective on the cause of the financial crisis, the United Kingdom government austerity programme: "It is clear that, partly due to past failings, the council is now having to make some drastic decisions to reduce services to a core offer. However, we can't ignore that some of the underlying causes of the challenges facing Northamptonshire, such as dramatic reductions to council budgets and severe demand for services, mean county authorities across the country face funding pressures of £3.2bn over the next two years."[41]

Structural changes

editIn early 2018, following the events above, Government-appointed commissioners took over control of the council's affairs. Consequently, the Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government commissioned an independent report which, in March 2018, proposed structural changes to local government in Northamptonshire. These changes, implemented on 1 April 2021, saw the existing county council and district councils abolished and two new unitary authorities created in their place.[42] One unitary authority, West Northamptonshire, consists of the former districts of Daventry, Northampton and South Northamptonshire; the other, North Northamptonshire, consists of the former East Northamptonshire district and the former boroughs of Corby, Kettering and Wellingborough.[43]

National representation

editNorthamptonshire returns seven Members of Parliament (MPs). As of 2024[update], five are currently from the Labour Party and two from the Conservative Party.[44] Several of the constituencies have been marginal in the past, including the Northampton seats, Wellingborough, Kettering, and Corby, which were all Labour seats before 2005. In the 2016 EU referendum, all of the Northamptonshire districts voted to Leave, most by a significant margin.

| Constituency | Member of Parliament | Political party |

|---|---|---|

| Corby & East Northamptonshire | Lee Barron | Labour |

| Daventry | Stuart Andrew | Conservative |

| Kettering | Rosie Wrighting | Labour |

| Northampton North | Lucy Rigby | Labour |

| Northampton South | Mike Reader | Labour |

| South Northamptonshire | Sarah Bool | Conservative |

| Wellingborough & Rushden | Gen Kitchen | Labour |

From 1993 until 2005, Northamptonshire County Council,[45] for which each of the 73 electoral divisions in the county elected a single councillor, had been held by the Labour Party; it had been under no overall control since 1981. The councils of the rural districts – Daventry, East Northamptonshire, and South Northamptonshire – were strongly Conservative, whereas the political composition of the urban districts was more mixed. At the 2003 local elections, Labour lost control of Kettering, Northampton, and Wellingborough, retaining only Corby. Elections for the entire County Council were held every four years – the last were held on 4 May 2017. The County Council used a leader and cabinet executive system and abolished its area committees in April 2006.

Economy

editHistorically, Northamptonshire's main industry was manufacturing of boots and shoes.[46] Many of the manufacturers closed down in the Thatcher era which in turn left many county people unemployed.[citation needed] Although R Griggs and Co Ltd, the manufacturer of Dr. Martens, still has its UK base in Wollaston near Wellingborough,[47] the shoe industry has deeply declined as manufacturing has moved away from England. There were over 2,000 shoemakers in the region in the mid 19th century, today the number is over 30 left.[48] Large employers include the breakfast cereal manufacturers Weetabix, in Burton Latimer, the Carlsberg brewery in Northampton, Avon Products, Nationwide Building Society, Siemens, Barclaycard, Saxby Bros Ltd and Golden Wonder.[49][50] In the west of the county is the Daventry International Railfreight Terminal;[51] which is a major rail freight terminal located on the West Coast Main Line near Rugby. Wellingborough also has a smaller railfreight depot[52] on Finedon Road, called Nelisons sidings.[53]

This is a chart of trend of the regional gross value added of Northamptonshire at current basic prices in millions of British Pounds Sterling (correct on 21 December 2005):[54]

| Year | Regional Gross Value Added[55] | Agriculture[56] | Industry[57] | Services[58] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 7,139 | 112 | 2,157 | 3,870 |

| 2000 | 9,743 | 79 | 3,035 | 6,630 |

| 2003 | 10,901 | 90 | 3,260 | 7,551 |

The region of Northamptonshire, Oxfordshire and the South Midlands has been described as "Motorsport Valley... a global hub" for the motor sport industry.[59][60] The Mercedes-AMG[61] and Aston Martin[62] Formula One teams have their bases at Brackley and Silverstone respectively, while Mercedes-Benz High Performance Engines[63] and, formerly, Cosworth,[64] are also in the county at Brixworth and Northampton respectively.

International motor racing takes place at Silverstone Circuit[65] and, formerly, Rockingham Motor Speedway;[66] Santa Pod Raceway is just over the border in Bedfordshire but has a Northamptonshire postcode.[67] A study commissioned by Northamptonshire Enterprise Ltd (NEL) reported that Northamptonshire's motorsport sites attract more than 2.1 million visitors per year who spend a total of more than £131 million within the county.[68]

Milton Keynes and South Midlands Growth area

editNorthamptonshire forms part of the Milton Keynes and South Midlands Growth area which also includes Milton Keynes, Aylesbury Vale and Bedfordshire. This area has been identified as an area which is due to have tens of thousands additional homes built between 2010 and 2020. In North Northamptonshire (Boroughs of Corby, Kettering, Wellingborough and East Northants), over 52,000 homes are planned or newly built and 47,000 new jobs are also planned.[69] In West Northamptonshire (boroughs of Northampton, Daventry and South Northants), over 48,000 homes are planned or newly built and 37,000 new jobs are planned.[70] To oversee the planned developments, two urban regeneration companies have been created: North Northants Development Company (NNDC)[69] and the West Northamptonshire Development Corporation.[70] The NNDC launched a controversial[71] campaign called North Londonshire to attract people from London to the county.[72] There is also a county-wide tourism campaign with the slogan Northamptonshire, Let yourself grow.[73]

Education

editSchools

editNorthamptonshire County Council previously operated a comprehensive system of state-funded secondary schools.[74] From May 2021 compulsory education in the county is administered by North Northamptonshire Council and West Northamptonshire Council. The county is home to private schools Oundle, Quinton House School, Wellingborough School, Spratton Hall School, Northampton High School.

The county's music and performing arts trust provides peripatetic music teaching to schools. It also supports 15 local Saturday morning music and performing arts centres around the county and provides a range of county-level music groups.

Colleges

editThere are seven colleges across the county, with the Tresham College of Further and Higher Education having four campuses in three towns: Corby, Kettering and Wellingborough.[75] Tresham, which was taken over by Bedford College in 2017 due to failed Ofsted inspections, provides further education and offers vocational courses and re-sit GCSEs.[76] It also offers Higher Education options in conjunction with several universities.[77] Other colleges in the county are: Fletton House, Knuston Hall, Moulton College, Northampton College, Northampton New College and The East Northamptonshire College.

University

editNorthamptonshire has one university, the University of Northampton. It has two campuses 2.5 miles (4.0 km) apart and 10,000 students.[78] It offers courses for needs and interests from foundation and undergraduate level to postgraduate, professional and doctoral qualifications. Subjects include traditional arts, humanities and sciences subjects, as well as entrepreneurship, product design and advertising.[79]

Healthcare

editHospitals

editThe main acute National Health Service hospitals in Northamptonshire Northampton General Hospital, which also operates Danetre Hospital in Daventry, and Kettering General Hospital. In the south-west of the county, the towns of Brackley, Towcester and surrounding villages are serviced by the Horton General Hospital in Banbury in neighbouring Oxfordshire for acute medical needs. A similar arrangement is in place for the town of Oundle and nearby villages, served by Peterborough City Hospital.

In February 2011 a new satellite out-patient centre opened at Nene Park, Irthlingborough to provide over 40,000 appointments a year, as well as a minor injury unit to serve Eastern Northamptonshire. This was opened to relieve pressure off Kettering General Hospital, and has also replaced the dated Rushden Memorial Clinic which provided at the time about 8,000 appointments a year, when open.[80]

Water contamination

editIn June 2008, Anglian Water found traces of Cryptosporidium in water supplies of Northamptonshire. The local reservoir at Pitsford was investigated and a European rabbit which had strayed into it,[81] causing the problem, was found. About 250,000 residents were affected;[82] by 14 July 2008, 13 cases of cryptosporidiosis attributed to water in Northampton had been reported.[83] Following the end of the investigation, Anglian Water lifted its boil notice for all affected areas on 4 July 2008.[84] Anglian Water revealed that it would pay up to £30 per household as compensation for customers hit by the water crisis.[85]

Transport

editThe gap in the hills at Watford Gap meant that many south-east to north-west routes passed through Northamptonshire. Watling Street, a Roman Road which is now part of the A5, passes through here, as did canals, railways and major roads in later years.

Roads

editMajor national roads, including the M1 motorway (London to Leeds) and the A14 (Rugby to Felixstowe), provide Northamptonshire with transport links both north–south and east–west. The A43 joins the M1 to the M40 motorway, passing through the south of the county to the junction west of Brackley, and the A45 links Northampton with Wellingborough and Peterborough.

The county road network (excluding trunk roads and motorways), managed by West Northamptonshire Council and North Northamptonshire Council, includes the A45 west of the M1 motorway, the A43 between Northampton and the county boundary near Stamford, the A361 between Kilsby and Banbury (Oxon) and all B, C and unclassified roads. Since 2009, these highways have been managed on behalf of the county council by MGWSP, a joint venture between May Gurney and WSP.

Rivers and canals

editTwo major canals – the Oxford and the Grand Union – join in the county at Braunston. Notable features include a flight of 17 locks on the Grand Union at Rothersthorpe, the canal museum at Stoke Bruerne and a tunnel at Blisworth which, at 2,813 metres (3,076 yd), is the third-longest navigable canal tunnel on the UK canal network.

A branch of the Grand Union Canal connects to the River Nene in Northampton and has been upgraded to a 'wide canal' in places and is known as the Nene Navigation. It is famous for its guillotine locks.

Railways

editTwo trunk railway routes, the Midland Main Line and the West Coast Main Line, cross the county. At its peak, Northamptonshire had 75 railway stations. It now has only six, at: Northampton and Long Buckby on the West Coast Main Line; Kettering, Wellingborough and Corby on the Midland Main Line; along with King's Sutton, only a few yards from the boundary with Oxfordshire on the Chiltern Main Line.

Before nationalisation of the railways in 1948 and the creation of British Railways, three of the Big Four railway companies operated in Northamptonshire: the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, London and North Eastern Railway and Great Western Railway. Only the Southern Railway was not represented. As of 2023, it is served by Chiltern Railways, East Midlands Railway, Avanti West Coast and West Midlands Trains.

- Corby rail history

Corby was described as the largest town in Britain without a railway station.[86] The railway running through the town from Kettering to Oakham in Rutland was previously used only by freight traffic and occasional diverted passenger trains that did not stop at the station. The line through Corby was once part of a main line to Nottingham through Melton Mowbray, but the stretch between Melton and Nottingham was closed in 1968. In the 1980s, an experimental passenger shuttle service ran between Corby and Kettering but was withdrawn a few years later.[87] On 23 February 2009, a new railway station opened, providing direct hourly access to London St Pancras. Following the opening of Corby Station, Rushden then became the largest town in the United Kingdom without a direct railway station. As of 2023, Corby is served by two regular EMR services per hour to London St Pancras International, branded as the Luton Airport Express and EMR Connect.

- Closed lines and stations

Railway services in Northamptonshire were reduced by the Beeching cuts in the 1960s.[88] Closure of the line connecting Northampton to Peterborough by way of Wellingborough, Thrapston, and Oundle left eastern Northamptonshire devoid of railways. Part of this route was reopened in 1977 as the Nene Valley Railway. A section of one of the closed lines, the Northampton to Market Harborough line, is now the Northampton & Lamport heritage railway, while the route as a whole forms a part of the National Cycle Network, as the Brampton Valley Way.

As early as 1897, Northamptonshire would have had its own Channel Tunnel rail link with the creation of the Great Central Railway, which was intended to connect to a tunnel under the English Channel. Although the complete project never came to fruition, the rail link through Northamptonshire was constructed, and had stations at Charwelton, Woodford Halse, Helmdon and Brackley. It became part of the London and North Eastern Railway in 1923 (and of British Railways in 1948) before its closure in 1966.[citation needed]

- Future

In June 2009, the Association of Train Operating Companies (ATOC) recommended opening a new station on the former Irchester railway station site for Rushden, Higham Ferrers and Irchester, called Rushden Parkway.[89]

The Rushden Historical Transport Society, operators of the Rushden, Higham and Wellingborough Railway, would like to see the railway fully reopen between Wellingborough and Higham Ferrers.

The route of the planned High Speed 2 railway line (between London and Birmingham) will go through the southern part of the county but without any stations.[citation needed]

Buses

editMost buses are operated by Stagecoach Midlands. Some town area routes have been named the Corby Star, Connect Kettering, Connect Wellingborough and Daventry Dart; the last three of these routes have route designations that include a letter (such as A, D1, W1, W2). Stagecoach's X4 route provides interurban links across the county, running between Northampton, Wellingborough, Kettering, Corby, Oundle and Peterborough. Uno and Centrebus also run services within the county,

Airports

editSywell Aerodrome, on the edge of Sywell village, has three grass runways and one concrete all-weather runway. It is, however, only 1000 metres long and therefore cannot be served by passenger jets.[90]

Northamptonshire is served predominantly by London Luton Airport in neighbouring Bedfordshire, which can be directly accessed by train every 30 minutes from Corby, Kettering and Wellingborough. London Stansted Airport in neighbouring is around 40 miles away and can be accessed by car but does not feature a direct rail connection from anywhere in the county.

Further afield, Northamptonshire is also within reach of Birmingham Airport and East Midlands Airport, both of which are around 45 miles away and can be accessed by direct trains from various stations within the county.

Media

editNewspapers

editThe two main newspapers in the county are the Northamptonshire Evening Telegraph and the Northampton Chronicle & Echo.[citation needed]

Television

editMost of Northamptonshire is served by BBC East and ITV Anglia which both are based in Norwich. A small part of the north of the county is covered by BBC East Midlands and ITV Central while a small part of southwest of the county primarily Brackley and the surrounding villages is covered by BBC South and ITV Meridian.

Radio

editBBC Radio Northampton, broadcasts on two FM frequencies: 104.2 MHz for the south and west of the county (including Northampton and surrounding area) and 103.6 MHz for the north of the county (including Kettering, Wellingborough and Corby). BBC Radio Northampton is situated on Abington Street, Northampton. These services are broadcast from the Moulton Park & Geddington transmitters. Some southern parts of the county (including Brackley) is served by BBC Radio Oxford broadcasting on 95.2 MHz.

There are three commercial radio stations in the county. The former Kettering and Corby Broadcasting Company (KCBC) station was called Connect Radio (97.2 and 107.4 MHz FM), following a merger with the Wellingborough-based station of the same name. It is now part of Smooth East Midlands. While both Heart East (96.6 MHz FM) and AM station Gold (1557 kHz) air very little local content as they form part of a national network. National digital radio is also available in Northamptonshire, though coverage is limited.[citation needed]

Corby is served by its own dedicated station, Corby Radio (96.3 FM), based in the town and focused on local content.[91]

Sport

editRugby union

editRugby Union is the most popular spectator sport in Northamptonshire[92], and it remains a major amateur sport with over 20 local clubs competing in the East Midlands RFU league system.

Northampton Saints

editThe county's most popular sports team by attendance, Northampton Saints, compete in the Gallagher Premiership and European Rugby Champions Cup, and are based at the 15,249 capacity [93] Franklin's Gardens.

During the 2023/24 Season, Northampton Saints finished the Premiership season top of the table, securing them a Home Semi-Final against the reigning Gallagher Premiership Champions Saracens, with Saints winning and becoming Finalists for the first time since winning the league in 2014. Saints played Bath Rugby at Twickenham Stadium in the Final on 8 June 2024. Northampton Saints won the Match beating Bath Rugby 25-21 and becoming the Gallagher Premiership Champions for the second time. Over 35,000 fans of the 82,000 capacity crowd traveled from Northamptonshire to watch the final in London.

To date, Saints have won seven major titles. They were European Champions in 2000, and English Champions in 2014 and 2024. They have also won the secondary European Rugby Challenge Cup twice, in 2009 and 2014, the Anglo-Welsh Cup in 2010, and the inaugural Premiership Rugby Cup in 2019.

Finally, the Saints have won the Second Division title three times; in 1990, 1996 and 2008.

Their biggest rivals are Leicester Tigers. The East Midlands Derby is one of the fiercest rivalries in English rugby union.[94][95]

Association football

editNorthamptonshire has twenty four football clubs operating in the top ten levels of the English football league system. The sport in the area is administered by the Northamptonshire Football Association, which is affiliated with the United Counties League, the Northamptonshire Combination Football League, the Northampton Town Football League, as well as the Peterborough and District Football League in neighbouring Cambridgeshire. Only two clubs in Northamptonshire to have competed in The Football League are Northampton Town and the defunct Rushden & Diamonds.

Northampton Town F.C.

editThe only fully-professional English football league club in the county is Northampton Town, which attracts between 4,000 and 6,000 fans on an average game day and has been part of the Football League since 1920.[96] Their home ground is Sixfields Stadium which opened in 1994. The first match there took place on 15 October against Barnet Football Club. The stadium can hold up to 7,500 people, with provisions for disabled fans.[97]

Other clubs

editThe county also a number of semi-professional sides that compete in levels 6 to 8 of the football pyramid. These are Kettering Town, Brackley Town, AFC Rushden & Diamonds, and Corby Town F.C. Nineteen teams compete in the United Counties League (UCL), a league operating at levels 9 and 10 of the English League system, and which encompasses all of Northamptonshire and parts of neighbouring counties.

Cricket

editNorthamptonshire County Cricket Club is in Division Two of the County Championship; the team (also known as The Steelbacks) play their home games at the County Cricket Ground, Northampton. They finished as runners-up in the Championship on four occasions in the period before it split into two divisions.

In 2013 the club won the Friends Life t20, beating Surrey in the final. Appearing in their third final in four years, the Steelbacks beat Durham by four wickets at Edgbaston in 2016 to lift the Natwest t20 Blast trophy for the second time. The club also won the NatWest Trophy on two occasions, and the Benson & Hedges Cup once.

Motor sport

editSilverstone is a major motor racing circuit, most notably used for the British Grand Prix. There is also a dedicated radio station for the circuit which broadcasts on 87.7 FM or 1602 MW when events are taking place. However, part of the circuit is across the border in Buckinghamshire. Rockingham Speedway, located near Corby, was one of the largest motor sport venues in the United Kingdom with 52,000 seats until it was closed permanently in 2018 to make way for a logistics hub for the automotive industry, hosting its last race in November of that year.[98] It was a US-style elliptical racing circuit (the largest of its kind outside of the United States), and is used extensively for all kinds of motor racing events. The Santa Pod drag racing circuit, venue for the FIA European Drag Racing Championships, is just across the border in Bedfordshire but has a NN postcode.

Two Formula One teams are based in Northamptonshire, with Mercedes at Brackley and Aston Martin in Silverstone. Aston Martin also have a secondary facility in Brackley, while Mercedes build engines for themselves, Aston Martin, McLaren and Williams at Brixworth. Cosworth, the high-performance engineering company, is based in Northampton.

Swimming and diving

editThere are seven competitive swimming clubs in the county: Northampton Swimming Club, Wellingborough Amateur Swimming Club, Rushden Swimming Club, Kettering Amateur Swimming Club, Corby Amateur Swimming Club, Daventry Dolphins Swimming Club, and Nene Valley Swimming Club. There is also one diving club: Corby Steel Diving Club. The main pool in the county is Corby East Midlands International Pool, which has an 8-lane 50m swimming pool with a floor that can adjust in depth to provide a 25m pool. The pool is home to the Northamptonshire Amateur Association's County Championships as well as some of the Youth Midland Championships.[99][100]

Northamptonshire is home to 2016 paralympian Ellie Robinson. She was talent-spotted in July 2012 and developed at Northampton Swimming Club, and was selected to compete for Great Britain at the 2016 IPC Swimming European Championships. She won there three bronze medals, and one silver medal.[101]

Culture

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2010) |

Jane Austen set her 1814 novel Mansfield Park mostly in Northamptonshire.

Melrose Plant, a prominent secondary protagonist in the Richard Jury series of mystery novels by Martha Grimes, resides in Northamptonshire, and much of the action in the books takes place there.

Kinky Boots, the 2005 British-American film and subsequent stage musical adaptation, was based on the true story of a traditional Northamptonshire shoe factory which, to stay afloat, entered the market for fetish footwear.

Rock and pop bands originating in the area have included Bauhaus, Temples, The Departure, New Cassettes, Raging Speedhorn and Defenestration. Richard Coles, an English musician, partnered in the 1980s with Jimmy Somerville to create the band The Communards. They achieved three top ten hits and made the No. 1 in 1986 with a version of the song "Don't Leave Me This Way". In 2012, The University of Northampton awarded Coles an honorary doctorate. From 2011 to 2022 he was the vicar of Finedon in Northamptonshire.

Northampton is the birthplace of composer Malcolm Arnold (born 21 October 1921) and of actor Marc Warren (born 20 March 1967).

Places of interest

edit| Key | |

| Abbey/Priory/Cathedral | |

| Accessible open space | |

| Amusement/Theme Park | |

| Castle | |

| Country Park | |

| English Heritage | |

| Forestry Commission | |

| Heritage railway | |

| Historic House | |

| Places of Worship | |

| |

Museum (free/not free) |

| National Trust | |

| Theatre | |

| Zoo | |

|

- 78 Derngate (Charles Rennie Mackintosh designed house in Northampton)

- All Saints, Northampton

- Althorp

- Apethorpe Palace

- Bannaventa

- Barnwell Castle

- Barnwell Country Park

- Barnwell Manor (former home of the Dukes of Gloucester)

- Billing Aquadrome

- Borough Hill Daventry (Iron Age hill fort)

- Borough Hill Roman villa

- Boughton House (home of the Dukes of Buccleuch)

- Blisworth tunnel

- Brackley (historic market town)

- Brampton Valley Way (linear park on a disused railway line)

- Brixworth Church (notably complete Anglo Saxon church)

- Brixworth Country Park

- Burghley House (home of the Marquess of Exeter)

- Canons Ashby House

- Canons Ashby Priory

- Castle Ashby (home of the Marquess of Northampton)

- The Castle Theatre (Wellingborough)

- Coton Manor Garden

- Cottesbrooke Hall

- Daventry Country Park

- Deene Park (home of the Marquess of Ailesbury)

- Delapré Abbey

- Derngate and Royal Theatre (Northampton)

- Drayton House

- Earls Barton Church

- Easton Neston

- Fermyn Woods Country Park

- Fotheringhay Castle & Church

- Franklin's Gardens

- Geddington's Eleanor cross

- Holdenby House

- Holy Sepulchre, Northampton (Norman Round church)

- Irchester Country Park

- Jurassic Way (long-distance footpath, Midshires Way section)

- Kelmarsh Hall

- Kirby Hall

- Knuston Hall

- Lamport Hall

- Lilford Hall

- Lyveden New Bield

- Nassington Prebendal Manor House

- Naseby Field

- Northampton & Lamport Railway

- Northampton Cathedral

- Northampton Guildhall

- Northampton Museum and Art Gallery

- Northamptonshire Ironstone Railway

- Oundle (historic market town)

- Piddington Roman Villa

- Pitsford Reservoir

- Raunds (historic market town)

- Raunds Church (home of the Raunds Wall Paintings and a 15th cent Mechanical Clock)

- Roadmender (live music venue)

- Rockingham Castle

- Rockingham Forest

- Rockingham Motor Speedway

- Rushden Hall

- Rushden, Higham and Wellingborough Railway

- Rushden Station Railway Museum

- Rushton Triangular Lodge

- St Peter’s, Northampton (notably complete and fine example of Norman architecture)

- Salcey Forest

- Silverstone Circuit

- Slapton Church (home of The Slapton Wall Paintings)

- Southwick Hall

- Stanwick Lakes

- Stoke Bruerne Canal Museum

- Sulgrave Manor (historic home of George Washington’s family, now run by the United States government)

- Summer Leys nature reserve

- Syresham

- Sywell Country Park

- Towcester Museum

- Watford Locks

- Wellingborough Museum

- Whittlewood Forest

- Wicksteed Park

Annual events

edit- Gretton Barn dance

- British Grand Prix at Silverstone

- Burghley Horse Trials

- Crick Boat Show

- Hollowell Steam Rally

- Northampton Balloon Festival

- Rothwell Fair

- Rushden Cavalcade

- St Crispin Street Fair

- Wellingborough Carnival

- World Conker Championships

- Buckby Feast

- Corby Highland Gathering

See also

edit- Custos Rotulorum of Northamptonshire - list of Keepers of the Rolls

- Grade I listed buildings in Northamptonshire

- High Sheriff of Northamptonshire

- History of Northamptonshire

- List of places in Northamptonshire

- Lord Lieutenant of Northamptonshire

- Northamptonshire (UK Parliament constituency) - historical list of MPs for the Northamptonshire constituency

- Northamptonshire Police

- Northamptonshire Police and Crime Commissioner

- Category:People from Northamptonshire

Notes

edit- ^ "No. 64463". The London Gazette. 17 July 2024. p. 13894.

- ^ "No. 64230". The London Gazette. 14 November 2024. p. 22966.

- ^ "Mid-2022 population estimates by Lieutenancy areas (as at 1997) for England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 24 June 2024. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ "Northamptonshire". collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "Northamptonshire". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ "Northamptonshire | England, UK History & Facts". Britannica. 13 June 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 768–770.

- ^ Greenall 1979, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Greenall 1979, p. 20.

- ^ BBC - History - Tribes of Britain. Retrieved 16 August 2009. Archived 25 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Greenall 1979, p. 29.

- ^ Wood, Michael (1986) The Domesday Quest p. 90, BBC Books, 1986 ISBN 0-563-52274-7.

- ^ Mills, A.D. (1998). A Dictionary of English Place-names. Second Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford. p256. ISBN 0-19-280074-4

- ^ "Rockingham Castle - Rockingham Castle, a home of history, Weddings, Corporate events and the Rockingham International Horse Trials". Rockinghamcastle.com. Archived from the original on 11 January 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ Stearns, Peter N., Langer. William L. The Encyclopedia of world history: ancient, medieval, and modern[permanent dead link]. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ Mott, Allan. BBC - Cambridgeshire - History: Mary Queen of Scots' last days Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Bbc.co.uk, Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ Edmonds. 1848. Notes on English history for the use of juvenile pupils. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ The Writings of George Washington: Life of Washington. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ GENUKI: Northamptonshire Genealogy: Bartholomew's Gazetteer of the British Isles, 1887 Archived 12 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Kellner.eclipse.co.uk, 11 August 2008. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Brookes, R., Whittaker, W.B. The General Gazetteer, or, Compendious geographical dictionary, in miniature. 1823. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Malte-Brun, C. Universal geography: or, A description of all parts of the world. 1832. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Andrews, R., Teller, M. The Rough Guide to Britain 2004. Rough Guides. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ University of Kentucky Genealogy Archives: Northamptonshire Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, accessed February 2019.

- ^ "English Partnerships - Corby". 23 June 2004. Archived from the original on 23 June 2004. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "English Partnerships - Northampton". 12 December 2004. Archived from the original on 12 December 2004. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "Northamptonshire Chamber :: Milton Keynes & South Midlands Growth Plan". 7 December 2009. Archived from the original on 7 December 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Peterborough Diocesan Registry". Peterboroughdiocesanregistry.co.uk. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ The Huntingdon and Peterborough Order 1964 (SI 1964/367), see Local Government Commission for England (1958–1967), Report and Proposals for the East Midlands General Review Area (Report No.3), 31 July 1961 and Report and Proposals for the Lincolnshire and East Anglia General Review Area (Report No.9), 7 May 1965

- ^ Annual Report of the Local Government Board. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1880. p. 501. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- ^ Local Government Act 1888

- ^ www.familysearch.org https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/Stamford_Baron_St._Martin,_Northamptonshire_Genealogy. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "Official information on visiting and holidaying in Northamptonshire". Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ UK Genealogy Archives: Transcript from Pigot & Co's Commercial Directory, 1830 Archived 2 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ Bathurst 2012, pp. 56–59.

- ^ Northamptonshire Genealogy: Bartholomew's Gazetteer of the British Isles, 1887 Archived 12 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ "Lincolnshire County Council". Thebythams.org.uk. 24 October 2005. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "Average weather for Northamptonshire (Moulton weather station)". Weather.msn.com. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- ^ Northamptonshire County Council: District and Borough Councils Archived 26 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine. 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ The Cambridgeshire (City of Peterborough) (Structural, Boundary and Electoral Changes) Order 1996 Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine (SI 1996/1878), see Local Government Commission for England (1992), Final Recommendations for the Future Local Government of Cambridgeshire, October 1994 and Final Recommendations on the Future Local Government of Basildon & Thurrock, Blackburn & Blackpool, Broxtowe, Gedling & Rushcliffe, Dartford & Gravesham, Gillingham & Rochester upon Medway, Exeter, Gloucester, Halton & Warrington, Huntingdonshire & Peterborough, Northampton, Norwich, Spelthorne and the Wrekin, December 1995

- ^ Johnston, Neil (2 August 2018). "'Bankrupt' Northamptonshire county council may cut to legal minimum". The Times. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

Hundreds of jobs are also at risk

- ^ Butler, Patrick (1 August 2018). "Northamptonshire's cash crisis driven by ideological folly, councillors told". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ "Northamptonshire County Council 'should be scrapped'". BBC News. 15 March 2018. Archived from the original on 19 March 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Northamptonshire County Council 'should be split up', finds damning report". ITV News. 15 March 2018. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Regional MPs & Local Authority Links". Northamptonshire Chamber. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Northamptonshire County Council website". Archived from the original on 31 May 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ GENUKI: Northamptonshire Genealogy: Bartholomew's Gazetteer of the British Isles Archived 12 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. 1887. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Kellysearch.co.uk: R Griggs & Co. Ltd Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Why Doc Martens Are So Expensive | So Expensive, 2 May 2020, retrieved 9 November 2022

- ^ "Northamptonshire Chamber :: Major Northamptonshire employers". 26 June 2010. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- ^ "Borough Council of Wellingborough - Document and File Downloads" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ "Dirft_holding". Archived from the original on 26 January 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- ^ FirstGBRf: FirstGBRf opens unique depot at Wellingborough Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. 12 June 2007. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ GB Railfreight: Locations, Wellingborough Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 11 November 2010

- ^ Regional Gross Value Added.Office for National Statistics Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. pp 240–253. 21 December 2005. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Components may not sum to totals due to rounding

- ^ includes hunting and forestry

- ^ includes energy and construction

- ^ includes financial intermediation services indirectly measured

- ^ Coe, N.M., Kelly, P.F, Wai-Chung Yeung, H. Economic geography: a contemporary introduction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2007. pp 141-143. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Russell Hotten. Motor racing battles to stay out of pits Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. TimesOnline. 27 March 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Official site of Mercedes GP Formula One Team: Contact us Archived 10 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Mercedes-gp.com, Retrieved 4 March 2010.

- ^ Force India F1 Team: Contact us Archived 1 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Forceindiaf1.com, Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Mercedes-Benz High Performance Engines Ltd: Contact Archived 23 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Mercedes-benz-hpe.com, Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Cosworth: Contact Archived 20 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Cosworth.com, Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Silverstone Official Website: Contact Numbers Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Getting to Rockingham Archived 3 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Rockingham.co.uk, Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Santa Pod Raceway: Contact/find us/postcode Archived 22 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Santapod.co.uk, Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ Motorsport to grow 30% in next decade Archived 21 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Northants Evening Telegraph. 25 June 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- ^ a b MSKM: North Northants Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Mksm.org.uk, Accessed 2 October 2010

- ^ a b MKSM: West Northants Archived 23 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Mksm.org.uk, Accessed 2 October 2010

- ^ Come to North Londonshire Archived 26 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Northants Evening Telegraph, Accessed 2 October 2010

- ^ North Londonshire: home page Archived 17 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 2 October 2010

- ^ Let yourself grow: home page Archived 11 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Letyourselfgrow.com, Accessed 2 October 2010

- ^ Northamptonshire County Council: Northamptonshire Schools Directory Archived 21 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ Tresham College: Our Campuses Archived 29 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ [1] Archived 1 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ Tresham College: Higher Education Archived 19 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ The University of Northampton: About Us Archived 23 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ The University of Northampton: Course finder Archived 18 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ "New £4.2m Irthlingborough outpatients clinic opens". BBC News. 7 February 2011. Archived from the original on 8 February 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- ^ Tite, Nick (14 July 2008). "Rabbit caused water contamination at Pitsford - Northants ET". Northants Evening Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ "Sickness bug found in tap water". BBC News. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ "BBC News". News at Ten, BBC One. BBC. 14 July 2008.

- ^ "Anglian Water" Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Press Release

- ^ "Water crisis: All clear for tap water - and up to £30 compensation! - Northampton Chronicle and Echo". Chronicle & Echo. 5 July 2008. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 22 August 2008.

- ^ Britten, Nick (23 February 2009). "Corby station". London: Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Network South East routes Archived 7 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "SMJR". Smjr.info. 19 September 2010. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ "Connecting Communities – Expanding Access to the Rail Network" (PDF). London: Association of Train Operating Companies. June 2009. p. 19. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "The Corby Radio Story". corbyradio.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ "Results". The Rugby Paper. No. 820. 2 June 2024. p. 28.

- ^ "A New Dawn". Northamptonsaints.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Northampton Saints v Leicester Tigers, Premiership semi-final: Gloves off for rugby's biggest grudge match". The Daily Telegraph. 15 May 2014. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "The 12 biggest rugby rivalries on the planet". Wales Online. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ "Northampton Town FC". Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "Sixfields Stadium - Northampton Town". Ntfc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ "Motorsport track closes after 17 years". 24 November 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "Northants ASA". northantsasa.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- ^ "Midland Championships". midlandchampionships.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- ^ "Ellie Robinson". Rio.paralympics.org.uk. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

References

edit- Bathurst, David (2012). Walking the county high points of England. Chichester: Summersdale, England. ISBN 978-1-84-953239-6.

- Greenall, R.L. (1979). A History of Northamptonshire. Bognor Regis, England: Phillimore & Co. Ltd. ISBN 1-86077-147-5..

External links

edit- Northamptonshire History Website Archived 10 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Former Northamptonshire County Council website, Archived 21 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine