In New Zealand, agriculture is the largest sector of the tradable economy. The country exported NZ$46.4 billion worth of agricultural products (raw and manufactured) in the 12 months to June 2019, 79.6% of the country's total exported goods.[1] The agriculture, forestry and fisheries sector directly contributed $12.653 billion (or 5.1%) of the national GDP in the 12 months to September 2020,[2] and employed 143,000 people, 5.9% of New Zealand's workforce, as of the 2018 census.[3]

New Zealand is unique in being the only developed country to be totally exposed to the international markets since subsidies, tax concessions and price supports for the agricultural sector were removed in the 1980s.[4] However, as of 2017, the New Zealand Government still provides state investment in infrastructure which supports agriculture.[5]

Pastoral farming is the major land use, but a significant amount of land is also devoted to horticulture.

New Zealand is a member of the Cairns Group, which is seeking to have free trade in agricultural goods.[6]

History

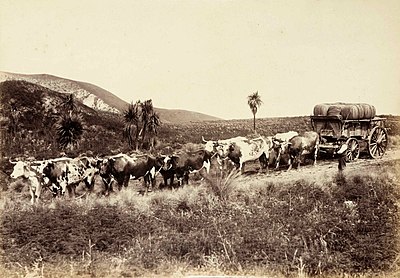

editFollowing their settlement of New Zealand in the 13th century, the Māori people developed economic systems involving hunting, foraging, and agriculture.[7] The Māori people valued land and especially horticulture, with many and various traditional Māori proverbs and legends emphasise the importance of gardening.[8] European and American explorers, missionaries and settlers introduced new animals and plants from 1769, and mass European settlement and land transfer led in the second half of the 19th century to an agricultural system featuring large Australian-style pastoral runs raising sheep. Immigrant land-hunger, innovations in refrigeration in the 1880s and the rise of dairying fostered the land reforms of John McKenzie in the 1890s, permitting an agricultural landscape of smaller family-based farms which became New Zealand's 20th-century agricultural norm (the oft-repeated cliché trumpets that agriculture/farming/farmers constitute "the backbone of the [New Zealand] economy") - challenged only in recent years by the growth in large-scale commercial industrial agriculture[9] and in lifestyle blocks.[10]

The Department of Agriculture controlled all meat-exporting slaughterhouses. By 1921 there were 32 abattoir inspectors and 86 inspectors of meat works. New Zealand mutton was marked as government inspected and pure.[11]

The government offered a number of subsidies during the 1970s to assist farmers after the United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community[12] and by the early 1980s government support provided some farmers with 40 percent of their income.[13] In 1984 the Labour government ended all farm subsidies under Rogernomics,[14] and by 1990 the agricultural industry became the most deregulated sector in New Zealand.[15] To stay competitive in the heavily subsidised European and US markets New Zealand farmers had to increase the efficiency of their operations.[16][17]

Pastoral farming

editIn Northland, the major form of pastoral farming is beef cattle. In the Waikato, Bay of Plenty, Taranaki and West Coast regions, dairy cattle predominate. Through the rest of New Zealand, sheep farming is the major rural activity, with beef cattle farming in the hills and high country, and dairying increasing in Canterbury, Otago and Southland.[18]

Dairy farming

editThere were 6.26 million dairy cattle in New Zealand as of June 2019.[19] For the 2019–20 season, 4.92 million cows were milked in 11,179 herds, producing 21.1 billion litres (4.6×109 imp gal; 5.6×109 US gal) of raw milk containing 1.9 million tonnes of milk solids (protein and milkfat).[20][21] Dairy farms covered an effective area of 17,304 km2 (6,681 sq mi), around 6.46% of New Zealand's total land area.[21]

The dairy cattle farming industry employed 39,264 people as of the 2018 census, 1.6% of New Zealand's workforce, making it the country's tenth-largest employment industry.[3] Around 56% of dairy farms in New Zealand are owner-operated as of 2015, while 29% are operated by sharemilkers and 14% are operated by contract milkers.[21] Herd-owning sharemilkers (formerly 50:50 sharemilkers) own their own herd, and are responsible for employing workers and the day-to-day operations of the farm, in return for receiving a percentage (typically 50%) of the milk income. Variable order sharemilkers do not own their own herd, and receive a lower percentage (typically 20-30%) of the milk income, while contract milkers are paid a fixed price per unit of milk.[22]

Dairy farming in New Zealand is primarily pasture-based. Dairy cattle primarily feed on grass, supplemented by silage, hay and other crops during winter and other times of slow pasture growth.[23] The dairy farming year in New Zealand typically runs from 1 June to 31 May. The first day of the new year, known as "Moving Day" or "Gypsy Day", sees a large-scale migration as sharemilkers and contract milkers take up new contracts and move herds and equipment between farms.[24][25] Calving typically takes place in late winter (July and August), and cows are milked for nine months before being dried off in late autumn (April and May).[26][23] Some farms employ winter milking, either wholly or partly, with calving in late summer and early autumn (February and March).[23]

Dairy farmers sell their milk to processors and are paid per kilogram of milk solids (kgMS). In the 2019–20 season, processors paid an average of $7.20 per kgMS (excluding GST), with the payout varying between $6.25 and $9.96 per kgMS depending on the processor.[21][27] Fonterra is the main processor of milk in New Zealand, processing 82 percent of all milk solids as of 2018. Other large dairy companies are Open Country Dairy (7.4%), Synlait and Westland Milk Products (3.4% each), Miraka (1.4%), Oceania Dairy (1.1%), and Tatua Co-operative Dairy Company (0.7%).[28]

Only 3% of dairy production is consumed domestically, with the rest exported.[23] New Zealand is the world's largest exporter of whole milk powder and butter, and the third-largest exporter (behind the European Union and the United States) of skim milk powder and cheese.[29]

Sheep farming

editThere were 26.82 million sheep in New Zealand as of June 2019.[19] The sheep population peaked at 70.3 million sheep in 1982 and has steadily declined ever since.[30]

In the 12 months to December 2020, 19.11 million lambs and 3.77 million adult sheep were processed, producing 362,250 tonnes of lamb and 97,300 tonnes of hogget and mutton.[31] 164,000 tonnes of clean wool was produced in 2006–7.[needs update] Around 95% of sheep meat and 90% of wool production is exported, with the rest consumed domestically.[23] In 2019, domestic consumption of lamb and mutton was 3.6 kg (7.9 lb) per capita.[32]

Beef farming

editThere were 3.89 million beef cattle in New Zealand as of June 2019.[19]

In the 12 months to December 2020, 1.59 million adult beef cattle and 1.15 million adult dairy cattle were processed, producing 698,380 tonnes of beef. In addition, 1.86 million calves and vealers were processed, producing 30,150 tonnes of veal.[31] Around 80% of beef and veal is exported, with the remaining 20% consumed domestically.[23] In 2019, domestic consumption of beef and veal was 11.6 kg (26 lb) per capita.[32]

Pig farming

editIn the first half of the 20th century, pigs were often farmed alongside dairy cattle. Most dairy processors collected cream only, so dairy farmers separated the whole milk into cream and skim milk and fed the pigs the skim milk. In the 1950s and 60s, improved technology saw dairy processors switch to collecting whole milk. Pig farming subsequently became specialised and the majority of farms moved to grain-producing areas such as Canterbury.[33][26]

There were 255,900 pigs in New Zealand in June 2019. Canterbury is by far the largest pig-farming region with 161,600 pigs, 63.1% of the national population.[19]

Pigs are usually kept indoors, either in gestation crates, farrowing crates, fattening pens, or group housing.[34]

In the 12 months to December 2020, 636,700 pigs were processed, producing 44,950 tonnes of meat.[31] In 2019, domestic consumption of pork, ham and bacon was 18.9 kg (42 lb) per capita.[32] Domestic production only meets around 45% of demand, with imported pork, ham and bacon, mainly from the European Union, North America and Australia, supplementing domestic supply. A small amount of meat is exported to supply nearby Pacific Island nations.[23]

Poultry farming

editThere were 3.87 million laying hens in New Zealand in June 2022, producing 1,100 million eggs annually.[35]

Before the 1960s, chicken meat was largely a by-product of the egg industry; chickens for sale were generally cockerels or spent hens. The introduction of broiler chickens in the 1960s saw the meat industry grow from 8,000 tonnes per year in 1962 to over 40,000 tonnes in the mid-1980s.[36] In the late 1990s, chicken overtook beef as the most-consumed meat in New Zealand.[23] In the 12 months to December 2020, 118.7 million chickens were raised for meat, producing 217,200 tonnes of chicken meat.[37]

Chickens account for over 98% of the country's poultry production, with turkeys and ducks accounting for the majority of the rest. Around 500,000 turkeys and 200,000 ducks are sold per year, with 90% of turkeys sold in the weeks preceding Christmas.[23]

In 2019, domestic consumption of chicken and other poultry was 41.1 kg (91 lb) per capita.[32] Most of the poultry meat produced in New Zealand is consumed domestically. Due to biosecurity restrictions, importing poultry meat and eggs into New Zealand is prohibited.[23]

Other pastoral farming

editDeer farming has increased dramatically from a herd of 150,000 in 1982 to 1.59 million in 2006, with 1,617 deer farms occupying 218,000 hectares of land in 2005.[38] $252 million of venison was exported in the year ending 30 September 2007. New Zealand is the largest exporter of farmed venison in the world.[39] In the 1970s and 80s there was a huge industry carrying out live deer recovery from forested areas of New Zealand. The deer are a pest animal that has a negative impact on the biodiversity of New Zealand. The deer-farm stock was bred from the recovered wild animals.[citation needed]

Goats are also farmed for meat, milk, and mohair, and to control weeds.[39]

Horticulture

editNew Zealand has around 125,200 hectares (309,000 acres) of horticultural land. Total horticultural exports in 2019 were valued at $6,200 million, of which $4,938 million (79.6%) come from three products: kiwifruit, wine, and apples.[40]

Fruit

editFruit growing occupies around 68,300 ha (169,000 acres) of land as of 2017. The largest crops by planted area are wine grapes (33,980 ha), kiwifruit (11,700 ha), apples (8,620 ha), avocadoes (3,980 ha), berries (2,320 ha), and stone fruit (2,140 ha).[40]

Wine grapes occupied 39,935 ha (98,680 acres) of land as of 2020, with the largest regions being Marlborough (27,808 ha), Hawke's Bay (5,034 ha), and Central Otago (1,930 ha). The largest varieties are sauvignon blanc (25,160 ha), pinot noir (5,642 ha), chardonnay (3,222 ha), pinot gris (2,593 ha) and merlot (1,087 ha).[41] Wine exports totalled $1,807 million in 2019.[40]

Kiwifruit is primarily grown in the Bay of Plenty, especially around Te Puke, but is also grown in small quantities in the Northland, Auckland, Gisborne and Tasman regions.[42] The fruit is picked in the autumn (March to May) and kept in coolstore until sold or exported. The New Zealand kiwifruit season runs from April to December; during the off-season, kiwifruit is imported to fulfil domestic demand.[43] There are around 2,750 kiwifruit growers, producing 157.7 million trays (567,720 tonnes) in the year to June 2019. Around 545,800 tonnes of kiwifruit was exported in the same period worth $2,302 million, making kiwifruit New Zealand's largest horticultural export by value.[40]

Apples are primarily grown in the Hawke's Bay and Tasman regions.[44] The two largest apple cultivars are Royal Gala and Braeburn, followed by Fuji, Scifresh (Jazz), Cripps Pink, Scired (Pacific Queen), and Scilate (Envy). All except Fuji and Cripps Pink were developed in New Zealand from cross-breeding or, in the case of Braeburn, a chance seedling.[40][45] Around 12% of apples are consumed domestically, 28% are processed domestically (mainly into juice), and 60% are exported.[44] Around 395,000 tonnes of apples, worth $829 million, were exported in the year to December 2019.[40]

Avocados are primarily grown in the subtropical areas of Northland and Bay of Plenty. Around 60% of the crop is exported, with $104.3 million worth of avocadoes being exported in the year to December 2019.[46][40]

Stone fruit, including peaches and nectarines, apricots, plums, and cherries, is primarily grown in Central Otago and Hawke's Bay. While apricots and cherries are exported, most stone fruit is consumed domestically.[47]

In 2019, fresh fruit exports totalled $3,392 million while processed fruit exports (excluding wine) totalled $138 million.[40]

Vegetables

editOutdoor vegetable growing occupies around 45,200 ha (112,000 acres) of land as of 2017, with Indoor vegetable growing occupying another 264 ha (650 acres). The largest crops by planted area are potatoes (9,450 ha), onions (6,010 ha), squash (5,790 ha), peas and beans (4,700 ha), sweet corn (3,870 ha), and brassicas (3,630 ha). The largest indoor crops are tomatoes (84 ha) and capsicums (61 ha).[40]

Auckland (namely Pukekohe), Manawatū-Whanganui (namely Ohakune and the Horowhenua district), and Canterbury are the major growing regions for potatoes, onions, brassicas (e.g. cabbage, broccoli and cauliflower), leafy vegetables (e.g. lettuce, silverbeet and spinach), and carrots and parsnips. Southland also grows a significant proportion of potatoes and carrots, and the Matamata area in Waikato and Hawke's Bay also grow a significant proportion of onions. Squash is mainly grown in Gisborne and Hawke's Bay. Sweet corn is mainly grown in Gisborne, Hawke's Bay, Marlborough and Canterbury. Kūmara (sweet potato) is almost exclusively grown in Northland.[48][49]

Due to their short shelf-life, most fresh vegetables are grown for domestic consumption and processing, with those exported mainly supplying nearby Pacific Island nations.[50] The largest vegetable exports are longer-life fresh vegetables such as onions and squash, along with processed vegetables such as french fries and potato chips, and frozen and canned peas, beans and sweet corn. In 2019, fresh vegetable exports totalled $304 million while processed vegetable exports totalled $396 million.[40]

Seeds and flowers

editSeeds and flowers are primarily grown in Canterbury, Auckland, Otago and Southland. In 2019, New Zealand exported $90 million of seeds, $43 million of bulbs and live plants, and $20 million of cut flowers.[40]

Arable crops

editAlmost all hay and silage is consumed on the same farm as it is produced. Most supplementary feed crops are grown in the South Island, where the colder climate forces additional feeding of stock during winter.[citation needed]

Cereals

editCereal crops occupies around 124,000 hectares (310,000 acres) of land as of June 2019. The largest crops by planted area are barley (55,500 ha), wheat (45,000 ha), maize (16,700 ha) and oats (2,100 ha).[51]

The majority of wheat, barley and oats is grown in the South Island, namely the Canterbury, Southland and Otago regions. Canterbury alone grows approximately 80-90% of the country's wheat, 68% of its barley and 60% of its oats. In contrast, almost all of the country's maize is grown in the North Island.[52]

Wheat, barley and oats are grown both for human consumption, malting, and for stock feed. Maize is grown as animal feed or for silage.[53]

Forestry

editMilling of New Zealand's extensive native forests was one of the earliest industries in the settlement of the country. The long, straight hardwood from the kauri was ideal for ship masts and spars. As the new colony was established, timber was the most common building material, and vast areas of native forest were cleared. Rimu, tōtara, matai, and miro were the favoured timbers. The Monterrey Pine, Pinus radiata was introduced to New Zealand in the 1850s.[54] It thrived in the conditions, reaching maturity in 28 years, much faster than in its native California. It was found to grow well in the infertile acidic soil of the volcanic plateau, where attempts at agriculture had failed. The Government initiated planting of exotic forests in 1899 at Whakarewarewa, near Rotorua. This was to address growing timber shortages as slow-growing native forests were exhausted.[55] In the 1930s, vast areas of land were planted in Pinus radiata by relief workers. The largest tract was the 188,000-hectare Kāingaroa forest, the largest plantation forest in the world. As the major forests matured, processing industries such as the Kinleith Mill at Tokoroa and the Tasman Mill at Kawerau were established.

Plantation forests of various sizes can now be found in all regions of New Zealand except Central Otago and Fiordland. In 2006 their total area was 1.8 million hectares, with 89% in Pinus radiata and 5% in Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii)[56] Log harvesting in 2006 was 18.8 million m3, down from 22.5 million m3 in 2003. This is projected to rise as high as 30 million m3 as newer forests mature. The value of all forestry exports (logs, chips, sawn timber, panels and paper products) for the year ended 31 March 2006 was $NZ 3.62 billion. This is projected to rise to $4.65 billion by 2011. Australia accounts for just over 25% of export value, mostly paper products, followed by Japan, South Korea, China and the United States.[56] Within the New Zealand economy, forestry accounts for approximately 4% of national GDP. On the global stage, the New Zealand forestry industry is a relatively small contributor in terms of production, accounting for 1% of global wood supply for industrial purposes.[57][needs update]

Aquaculture

editAquaculture started in New Zealand in the late 1960s and is dominated by mussels, oysters and salmon. In 2007, aquaculture generated about NZ$360 million in sales on an area of 7,700 hectares with a total of $240 million earned in exports. In 2006, the aquaculture industry in New Zealand developed a strategy aimed at achieving a sustainable annual billion NZ dollar business by 2025. In 2007, the government reacted by offering more support to the growing industry.[needs update]

Beekeeping

editNew Zealand had 2,602 beekeepers at the end of 2007, who owned 313,399 hives. Total honey production was 9700 tonnes. Pollen, beeswax, and propolis are also produced. Beekeepers provide pollination services to horticulturalists, which generates more income than the products of bee culture. Approximately 20–25,000 queen bees, and 20 tonnes of packaged bees (which include worker bees and a queen) are exported live each year.[58]

Environmental issues

editBoth the original Māori people and the European colonists made huge changes to New Zealand over a relatively short time. Māori burned forest to flush out game and to encourage the growth of bracken fern, which was used as a food source, and practised agriculture using plants they brought from tropical Polynesia. The Europeans logged and burned off a third of the forest cover to convert land to pastoral farming.

In 1993, the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research summarised available data on the quality of water in rivers. They concluded that "lowland river reaches in agriculturally developed catchments are in poor condition" reflecting "agriculturally derived diffuse and point source waste inputs in isolation or in addition to urban or industrial waste inputs". The key contaminants identified in lowland rivers were dissolved inorganic nitrogen, dissolved reactive phosphorus and faecal contamination. Small streams in dairy farming areas were identified as being in very poor condition.[59] New Zealand's rivers and lakes are becoming increasingly nutrient enriched and degraded by nitrogen, animal faecal matter, and eroded sediment.[60] Many waterways are now unsafe for swimming. Fish and Game New Zealand launched a "dirty dairying" campaign to highlight the effect of intensive agriculture on waterways. Fonterra, the largest dairy company in New Zealand, in conjunction with government agencies responded with the Dairying and Clean Streams Accord. In 2009, the Crafar Farms group of dairy farms in the North Island became known as the 'poster boys for dirty dairying' after a string of prosecutions in the Environment Court for unlawful discharges of dairy effluent.[61][62]

In 2004 the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment released a report on the environmental effects of farming in New Zealand.[63] It noted that the trend was towards an increasing pressure on New Zealand's natural capital. Between 1994 and 2002 the number of dairy cows increased by 34% and the land area used grew by just 12% resulting in a more intensive land use. In the same period synthetic fertiliser use across all sectors grew by 21% and urea use grew by 160%.[citation needed]

Almost half of the greenhouse gas emissions in New Zealand are due to the agricultural sector. A portion of this is due to methane from belching ruminants. An agricultural emissions research levy was proposed, quickly becoming known as the "Fart Tax".[64] The proposed levy encountered opposition from the farming sector and the National Party, resulting in plans for the levy being abandoned. The Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium was formed as an alternative to imposing the levy on farmers.

Organic farming

editOrganic farming practices began on a commercial scale in the 1980s and is now an increasing segment of the market with some of the larger companies such as Wattie's becoming involved.

Agricultural pests

editA number of plant and animal introductions into New Zealand has reduced the income from farming. Tight border controls to improve biosecurity have been put into place to ensure any new and unwanted pests and diseases do not enter the country. Monitoring is done around sea and airports to check for any incursions.

Animal pests

editThe common brushtail possum was introduced from Australia to establish a fur trade. It soon became one of New Zealand's most problematic invasive species because of the huge effect on the biodiversity of New Zealand, as well affecting agricultural production, as it is a vector for bovine tuberculosis. The disease is now endemic in possums across approximately 38 per cent of New Zealand (known as 'vector risk areas'). In these areas, nearly 70 per cent of new herd infections can be traced back to possums or ferrets. The Biosecurity Act 1993, which established a National Pest Management Strategy, is the legislation behind control of the disease in New Zealand. The Animal Health Board (AHB) operates a nationwide programme of cattle testing and possum control with the goal of eradicating M. bovis from wild vector species across 2.5 million hectares – or one quarter – of New Zealand's at-risk areas by 2026 and, eventually, eradicating the disease entirely.[65]

Possums are controlled through a combination of trapping, ground-baiting and, where other methods are impractical, aerial treatment with 1080 poison.[66]

From 1979 to 1984, possum control was stopped due to lack of funding. In spite of regular and frequent TB testing of cattle herds, the number of infected herds snowballed and continued to increase until 1994.[67] The area of New Zealand where there were TB wild animals expanded from about 10 to 40 per cent.

That possums are such effective transmitters of TB appears to be facilitated by their behaviour once they succumb to the disease. Terminally ill TB possums will show increasingly erratic behaviour, such as venturing out during the daytime to get enough food to eat, and seeking out buildings in which to keep warm. As a consequence they may wander onto paddocks, where they naturally attract the attention of inquisitive cattle and deer. This behaviour has been captured on video.[68]

The introduced Canada goose became prolific and began to adversely affect pastures and crops. In 2011 restrictions on hunting them were dropped to allow them to be culled.

Plant pests

editGorse was introduced as a hedgerow plant but has become the most expensive agricultural plant pest costing millions of dollars in efforts to control its spread over farmland.

Other serious pasture and crop land plant pests are nodding thistle (Carduus nutans), Californian thistle (Cirsium arvense), ragwort (Senecio jacobaea), broom (Cytisus scoparius), giant buttercup (Ranunculus acris), fat-hen (Chenopodium album), willow weed (Polygonum persicaria), and hawkweed (Hieracium species).[69]

Biosecurity

editBecause of its geographical isolation New Zealand is free of some pest and diseases that are problematic for agricultural production in other countries. With a high level of international trade and large numbers of inbound tourists biosecurity is of great importance since any new pest or diseases brought into the country could potentially have a huge effect on the economy of New Zealand.

There have been no outbreaks of foot-and-mouth disease in New Zealand. If an outbreak did occur there is potential for severe economic losses given that agricultural exports are a large segment of exports.[70] New Zealand has strict biosecurity[71] measures in place to prevent the introduction of unwanted pests and diseases.

In 2017, some cattle near Oamaru in the South Island were found to be Mycoplasma bovis positive, see 2017 Mycoplasma bovis outbreak.

Tenure review

editMany areas of the high country of the South Island were set up as large sheep and cattle stations in the late 19th century. Much of this land was leased from The Crown but after the passing of the Crown Pastoral Land Act 1998 the leases were reviewed. Environmentalists and academics raised concerns about the process saying that farmers were gaining an advantage and that conservation issues were not being resolved. Farmers were concerned that environmentalists and academics used the tenure review process to lock land up for conservation purposes without regard to the property rights of farmers or planning for how to manage that land in the future, and much land has been degraded by pests and weeds since it was retired from farming.

Policy, promotion and politics

editThe Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), the government agency responsible for the agricultural sector, has both policy and operational arms.

Federated Farmers, a large and influential lobby group, represents farmers' interests. It has a voluntary membership which stands[when?] at over 26,000.

The Soil & Health Association of New Zealand, established in 1941, promotes organic food and farming.

The New Zealand Young Farmers, a national organisation formed in 1927 with regional clubs throughout the country, runs the annual Young Farmer Contest.

Irrigation New Zealand, a national body representing farmers who use irrigation as well as the irrigation industry, opposes water conservation orders.[72]

Foreign ownership

editAlmost 180,000 hectares of farming land was purchased or leased by foreign interests between 2010 and 2021. The United States is the biggest nation owning land in New Zealand, China is second.[73][74]

There is opposition to foreign ownership in New Zealand, The populist New Zealand First party is the largest party opposed to foreign ownership. In a 2011 Poll found that 82% believed foreign ownership of farms and agriculture land was a "bad thing". Only 10% believed it a "good thing" and 8% were unsure.[75]

Future of New Zealand agriculture

editThere are two main views on the immediate future of New Zealand agriculture. One is that, due to fast-rising consumer demand in India and China, the world is entering a golden age for commodities, and New Zealand is well placed to take advantage of this. The other view is that New Zealand will only gain limited rewards from this boom because of increasing production competition from developing countries. For New Zealand to remain competitive, farmers will either have to intensify production to remain commodity producers (increasing stock and fertiliser per hectare) or, instead, become producers of higher value, more customised products.[60]

AgResearch Ltd (New Zealand's largest Crown Research Institute) believes that new technologies will allow New Zealand farmers to double their output by 2020, while simultaneously reducing greenhouse-gas emissions and other detrimental environmental impacts associated with farming practices.[60]

Joint research by Healthier Lives and Our Land and Water examined agricultural scenarios aimed at optimising a healthy diet while minimising nitrate and phosphate water pollution. They suggested that New Zealand could meet its environmental goals by changing land use in parts of the country that would otherwise be unable to meet water-quality targets, for example as a result of agricultural contamination. This research was included in a Ministerial briefing to support a New Zealand National Food Strategy.[76]

Impact on New Zealand culture

editRural New Zealand has affected the culture of New Zealand.

Country Calendar is a factual television programme about farming methods and country life, and is watched by both rural and urban New Zealanders. The show first premièred on 6 March 1966, and is the country's longest-running locally-made television series.[77]

The gumboot, a waterproof boot commonly used by farmers and others, is a cultural icon with Taihape hosting an annual Gumboot Day. Fred Dagg, a comedy character created by John Clarke, was a stereotypical farmer wearing a black singlet, shorts and gumboots.

Number 8 wire is used for fencing and has become part of the cultural lexicon. It is used for all manner of tasks and it describes the do it yourself mentality of New Zealanders.

Agricultural and Pastoral shows

editA fixture in many rural towns, the annual Agricultural and Pastoral (A&P) show[78] organises competitions for the best livestock and farm produce. Carnivals, sideshows, equestrian events and craft competitions also take place in association with A&P shows.

See also

edit- Agricultural and Marketing Research and Development Trust

- Animal welfare in New Zealand

- Fishing industry in New Zealand

- Flax in New Zealand

- Kiwifruit industry in New Zealand

- Genetic engineering in New Zealand

- Pesticides in New Zealand

- Hump and hollow, a pasture improvement technique

- National Animal Identification and Tracing

- Station (New Zealand agriculture)

- Crafar Farms

- Animal Health Board

- Regulation of animal research in New Zealand

References

edit- ^ "New Zealand's primary sector exports reach a record $46.4 billion". Stuff. 16 September 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Gross domestic product: September 2020 quarter | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b "2018 Census totals by topic" (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet). Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ Brendan Hutching, ed. (2006). New Zealand Official Yearbook. Statistics New Zealand. p. 359. ISBN 978-1-86953-638-1.

- ^ "Background". Crown Irrigation Investments. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ "Agricultural trade negotiations". New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ^

Firth, Raymond (2012) [1929]. "The Maori and His Economic Resources". Primitive Economics of the New Zealand Maori (reprint ed.). Abingdon: Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 9781136505362. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

[...] separating tribes according as to whether their main livelihood was gained by agriculture, fishing, or the utilization of forest products. [...] In general the tribes of Auckland and the North, the Bay of Plenty, Tauranga and the remainder of the East Coast, Taranaki, Nelson, and the Kaiapohia district practised agriculture. The people of the West Coast and the larger part of the South Island, as also Taupo and the Urewera, gained their living chiefly from forest products, augmented largely in the case of Whanganui by eels. Another specific source of food was worked by the Arawa tribes, with whom fresh-water fish, crayfish and kakahi (mussels) from the lakes formed a substantial part of the provision stocks. The fern root was available to all tribes, and constituted a staple food-product, while the coastal people, especially to the east, drew a large portion of their sustenance from fish.

- ^

Beamer, Kamanamaikalani; Tau, Te Maire; Vitousek, Peter M. (29 November 2022). "Mahinga kai no Tonganui (New Zealand): Making a Living in South Polynesia, 1250-1800". Islands and Cultures: How Pacific Islands Provide Paths toward Sustainability. Yale University Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780300268393. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

Canoe traditions about kumara, by far the main cultigen in New Zealand, are detailed but contradictory.

- ^

Neave, Mel; Mulligan, Martin (20 November 2014). "Food and agriculture". In Mulligan, Martin (ed.). An Introduction to Sustainability: Environmental, Social and Personal Perspectives. London: Routledge. p. 214. ISBN 9781134548750. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

[...] industrial agriculture is capital and input intensive. It is usually undertaken on a large spatial scale and is widely used in the developed world, including in North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand.

- ^

Markantoni, Marianna; Koster, Sierdjan; Strijker, Dirk (28 February 2014). "Side-activity entrepreneur: lifestyle or economically oriented?". In Karlsson, Charlie; Johansson, Börje; Stough, Roger R. (eds.). Agglomeration, Clusters and Entrepreneurship: Studies in Regional Economic Development. New Horizons in Regional Science Series. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 145. ISBN 9781783472635. Retrieved 3 March 2023.

[...] it is relevant to mention the term lifestyle block. The term was first introduced by real estate agents in the 1980s in New Zealand to describe rural smallholdings.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Nightingale, Tony (March 2009). "Government and agriculture – Subsidies and changing markets, 1946–1983". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ Pickford, John (October 2004). "New Zealand's hardy farm spirit". BBC news.

- ^ Edwards, Chris; DeHaven, Tad (March 2002). "Save the Farms – End the Subsidies". The Washington Post. Cato Institute.

- ^ Nightingale, Tony (June 2010). "Government and agriculture – Deregulation and environmental regulations, 1984 onwards". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ Arnold, Wayne (August 2007). "Surviving Without Subsidies". The New York Times.

- ^ St Clair, Tony (July 2002). "Farming without subsidies – a better way: Why New Zealand agriculture is a world leader". European Voice. Retrieved 22 January 2011.

- ^ New Zealand Official Yearbook, 2008, p 359

- ^ a b c d "Agricultural production statistics: June 2019 (final) | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "NZ dairy production hits record in 2020, despite lower cow numbers". NZ Herald. 26 November 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d "New Zealand Dairy Statistics 2019-20". www.dairynz.co.nz. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "Sharemilker". www.careers.govt.nz. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Livestock production in New Zealand. Kevin J. Stafford. Auckland, New Zealand. 2017. ISBN 978-0-9941363-1-2. OCLC 978284784.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "'Nervous excitedness' on dairy farm moving day". Stuff. 1 June 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ "Thousands of farmers on the move for annual Gypsy Day". TVNZ. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ a b Stringleman, Hugh; Scrimgeour, Frank (24 November 2008). "Dairying and dairy products - Pattern of milk production". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Dairy industry payout history". interest.co.nz. 18 October 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Fox, Andrea (3 October 2018). "Fonterra hold on raw milk market still 80 per cent despite predictions". NZ Herald. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Dairy market review - Emerging trends and outlook" (PDF). Food and Agriculture Organization. December 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Stringleman, Hugh; Peden, Robert (3 March 2015). "Changes from the 20th century - Sheep framing". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Livestock slaughtering statistics: December 2020 – Infoshare tables | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Agricultural output - Meat consumption - OECD Data". theOECD. Retrieved 7 March 2021.

- ^ Gillingham, Allan (24 November 2008). "Pigs and the pork industry - Pig farming". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Animal Welfare". NZ Pork Board. June 2010. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2010.

- ^ "Group: Agriculture - AGR -- Table: Variable by Total New Zealand (Annual-Jun) -- Infoshare". Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Burton, David (5 September 2013). "Food - Meat". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "Primary production – poultry: December 2020 quarter and year – Infoshare tables | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ New Zealand Official Yearbook, 2008, p 358

- ^ a b New Zealand Official Yearbook, 2008, pp 360–61

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Fresh Facts: New Zealand Horticulture" (PDF). Plant & Food Research. 2019. ISSN 1177-2190.

- ^ "Vineyard Register Report 2019-2022" (PDF). New Zealand Winegrowers. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Hugh; Haggerty, Julia (24 November 2008). "Kiwifruit - Growing kiwifruit". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 7 February 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Campbell, Hugh; Haggerty, Julia (24 November 2008). "Kiwifruit - The production year". teara.govt.nz. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ a b Palmer, John (24 November 2008). "Apples and pears - Pipfruit in New Zealand". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Palmer, John (24 November 2008). "Apples and pears - Cultivars". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Scarrow, Sandy (24 November 2008). "Citrus, berries, exotic fruit and nuts - Avocados and persimmons". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Dawkins, Marie (24 November 2008). "Stone fruit and the summerfruit industry". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Wassilieff, Maggy (24 November 2008). "Market gardens and production nurseries - Major vegetable crops". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 19 May 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Wassilieff, Maggy (24 November 2008). "Market gardens and production nurseries - Other outdoor crops". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 19 May 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ "New Zealand domestic vegetable production: the growing story" (PDF). Horticulture New Zealand. 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ "Agricultural production statistics: June 2020 (provisional) | Stats NZ". www.stats.govt.nz. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ Zydenbos, Sue (24 November 2008). "Arable farming - Arable crops today". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ Zydenbos, Sue (24 November 2008). "Arable farming - Markets and processing". teara.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 8 April 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ New Zealand Official yearbook, 1990

- ^ McKinnon, Malcolm (20 December 2010). "Volcanic Plateau region". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- ^ a b "Situation and outlook for New Zealand agriculture and forestry". NZ Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. August 2007. Archived from the original on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ "The Forestry Industry in New Zealand". Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2009.

- ^ New Zealand Official Yearbook, 2008, p 370

- ^ Smith, CM; Vant, WN; Smith, DG; Cooper, AB; Wilcock, RL (April 1993). "Freshwater quality in New Zealand and the influence of agriculture". Consultancy Report No. MAF056. National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

- ^ a b c Oram, R. (2007). The RMA now and in the future, paper presented at the Beyond the RMA conference, Environmental Defence Society, Auckland, NZ, 30–31 May

- ^ Leaman, Aaron; Neems, Jeff (29 August 2009). "Acting 'too late' costs farmers $90k". Waikato Times. Fairfax Media Ltd. Retrieved 31 May 2010.

- ^ Kissun, Sudesh (25 September 2009). "Things could have been done better: Crafar". Rural News. Rural News Group Limited. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

The Reporoa farmer, used by environmental groups as a poster boy for dirty dairying, is unhappy with some things happening on his farms

- ^ PCE (October 2004). Growing for good: Intensive farming, sustainability and New Zealand's environment. Wellington: Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. Archived from the original on 14 October 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- ^ "Images: Farmers Fart Tax Protest at Parliament". scoop.co.nz. 4 September 2003. Retrieved 1 April 2009.

- ^ "TBfree New Zealand programme". Archived from the original on 30 January 2011.

- ^ "The use of 1080 for pest control – 3.1 Possums as reservoirs of bovine tuberculosis". 2011. Archived from the original on 19 December 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Future freedom from bovine TB, Graham Nugent (Landcare Research)". 2011. Archived from the original on 30 March 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ "Dr Paul Livingstone letter to the editor". Gisborne Herald. 26 May 2011. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- ^ Taylor, Rowan (1997). Ian Smith (ed.). The State of New Zealand's Environment 1997. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment. ISBN 0-478-09000-5.

- ^ Biosecurity New Zealand Archived 14 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine Foot and mouth disease

- ^ "For Quanmail email | MPI - Ministry for Primary Industries. A New Zealand Government Department".

- ^ Curtis, Andrew (6 October 2017). "Andrew Curtis: Water conservation orders dam up vital discussion". Stuff. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- ^ "US buying up our primary industries". Radio New Zealand. 12 July 2021.

- ^ "Who is buying up our farm land? The largest foreign owners of NZ soil". 24 September 2023.

- ^ "Kiwis against farms to foreigners - poll". 2 November 2011.

- ^ McDowell, Richard W.; Herzig, Alexander; van der Weerden, Tony J.; Cleghorn, Christine; Kaye-Blake, William (26 May 2024). "Growing for good: producing a healthy, low greenhouse gas and water quality footprint diet in Aotearoa, New Zealand". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 54 (3): 325–349. Bibcode:2024JRSNZ..54..325M. doi:10.1080/03036758.2022.2137532. ISSN 0303-6758. PMC 11459733. PMID 39439877.

- ^ "1966 - key events - The 1960s | NZHistory, New Zealand history online". nzhistory.govt.nz. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Royal Agricultural Society

Further reading

edit- A lasting Legacy – A 125-year history of New Zealand Farming since the first Frozen Meat Shipment, Ed. Colin Williscroft PMP, NZ Rural Press Limited, Auckland, 2007

External links

edit- Ministry for Primary Industries

- Statistics New Zealand – Primary production page

- MPI Biosecurity New Zealand

- Organics Aotearoa New Zealand

- Soil & Health Association of New Zealand

- Country-Wide magazine – In-depth information helping farmers make more money (based in New Zealand)

- The Deer Farmer – The Deer Farmer Business Independent: The world's premier deer farming journal (based in New Zealand)

- The Farmer in New Zealand (1941 Centennial publication)

- The TBfree New Zealand programme