Mount Marcy (Mohawk: Tewawe'éstha) is the highest point in the U.S. state of New York, with an elevation of 5,343.1 feet (1,628.6 m). It is located in the town of Keene in Essex County. The mountain is in the heart of the High Peaks Wilderness Area in Adirondack Park. Like the surrounding Adirondack Mountains, Marcy was heavily affected by large glaciers during recent ice ages, which deposited boulders on the mountain slopes and carved valleys and depressions on the mountain. One such depression is today filled by Lake Tear of the Clouds, which is often cited as the highest source of the Hudson River. The majority of the mountain is covered by hardwood and spruce-fir forests, although the highest few hundred feet are above the tree line. The peak is dominated by rocky outcrops, lichens, and alpine plants. The mountain supports a diverse number of woodland mammals and birds.

| Mount Marcy | |

|---|---|

Mount Marcy (Photo taken from Mount Skylight, looking north) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,343 ft (1,629 m) NAVD 88[1] |

| Listing | |

| Coordinates | 44°06′46″N 73°55′25″W / 44.112734392°N 73.923725878°W[1] |

| Naming | |

| Etymology | Named for William L. Marcy |

| Native name | Tewawe'éstha (Mohawk) |

| Geography | |

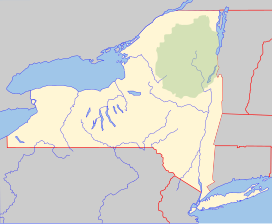

Location in Adirondack Park | |

| Location | Keene, Essex County, New York, U.S. |

| Parent range | Adirondack Mountains |

| Topo map | USGS Mount Marcy |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | August 5, 1837, by Ebenezer Emmons and party[a] |

| Easiest route | Hike (Van Hoevenberg Trail) |

Mount Marcy's stature and expansive views make it a popular destination for hikers, who crowd its summit in the summer months. Multiple approaches to the summit are available from the north and south, with the most popular route being the Van Hoevenberg Trail. The first recorded ascent of the mountain was made by a party led by Ebenezer Emmons[a] on August 5, 1837, who named it after New York governor William L. Marcy. One of the mountain's most notable ascents was made in 1901, when Theodore Roosevelt climbed it with his family, and learned during his descent that William McKinley was dying and he was to become President of the United States.

Name

editThe mountain is known as Tewawe'éstha in the Mohawk language.[4] The mountain was known as Wah-um-de-neg, meaning "always white", in the Missisquoi Abenaki Tribe.[5] Another Abenaki name for it and the surrounding mountains was Wawobadenik, meaning "white mountains".[6]

The contemporary name Mount Marcy was provided by Ebenezer Emmons following his ascent of the mountain in August 1837. The mountain is named after William L. Marcy, the 19th-century Governor of New York, who authorized the environmental survey that explored the area.[7] In September 1837, the area was visited by poet and author Charles Fenno Hoffman, who proposed the alternative name Tahawus, a Seneca term which has been translated as "cloud-splitter" or "he splits the sky". The alternative name became popular during the 19th century, and the nearby village at Lower Works was renamed Tahawus in 1847. Many New Yorkers advocated for it to become the official name. A misconception arose that this was an original indigenous name for the peak, although there is no documented use of it prior to Hoffman.[8][b]

Geography

editMount Marcy is the highest point in New York,[10] the highest peak in the Adirondack Mountains, and the highest of the Adirondack High Peaks,[11] with an elevation of 5,343.1 feet (1,628.6 m).[1] The mountain is located in the High Peaks Wilderness Area,[12] in the town of Keene in Essex County. Three shorter peaks are located on the flanks of Marcy: Gray Peak 0.6 miles (0.97 km) to the west, Little Marcy 0.8 miles (1.3 km) to the northeast, and an unnamed peak 1.2 miles (1.9 km) to the northwest.[13] Lake Tear of the Clouds, at the col between Mounts Marcy and Skylight, is often cited as the highest source of the Hudson River.[14][15] Between Mount Marcy and Mount Haystack lies Panther Gorge. A large rock slide on the southern slope of the mountain, now called the Old Slide, was incorporated into the first cut trail to the summit, which approached from Panther Gorge.[16]

Geology

editMount Marcy is composed of anorthosite rock formed approximately 1.1 billion years ago. During the Pleistocene Epoch, large glaciers formed across the Adirondack Mountains, carving new valleys and depositing erratic rocks across the mountains. The last glacial retreat of the Pleistocene occurred 12,000 years ago.[17] Numerous cirques were left on the mountain slopes by water as it repeatedly froze and thawed, including a depression on the northeast slope known as the snowbowl, and another on the south slope which has now been filled by Lake Tear of the Clouds. The mountain, along with the surrounding Adirondack region, is currently rising at a rate of 2-3 millimeters per year.[18]

History

editThe earliest recorded ascent of Mount Marcy was on August 5, 1837, by a large party led by state geologist Ebenezer Emmons measuring the highest peaks in the region.[19][20][a] Interest in recreational climbs of the mountain increased after 1849, when mountain guide Orson Schofield Phelps moved to the area. Phelps would ascend the mountain over 100 times and cut the first two trails to the peak.[23]

Surveying teams led by Verplanck Colvin made several important ascents of Mount Marcy in the 1870s. Colvin's team measured the mountain's elevation by leveling in 1875,[24] and a signal tower was erected at the summit in 1877.[25] After observing the effects of deforestation during his travels in the Adirondacks, Colvin proposed the creation of a park in the mountains.[26] Most of the Adirondack region, including Mount Marcy, had been sold to private landowners shortly after the American Revolution. In 1922, the state of New York acquired the land containing the summit to add to the state forest preserve.[27]

Vice President Theodore Roosevelt was on a vacation in the Adirondacks when President William McKinley was shot by an assassin on September 6, 1901. Roosevelt rushed to Buffalo to see the president, but believed he would recover and resumed his trip.[28] On September 13, when it became clear McKinley was dying, Roosevelt was staying at Tahawus, and spent the morning ascending Mount Marcy with his family. A messenger had to be dispatched to deliver the news and reached the party at Lake Tear of the Clouds during their descent.[29] They hiked back to their lodge, where Roosevelt hired a stage coach to take him to the North Creek train station. There, Roosevelt was informed that McKinley had died, and the new president took the train to Buffalo to be sworn in.[30] The route from Long Lake to North Creek has been designated as the Roosevelt-Marcy Trail.[31]

Marcy's popularity as a hiking destination has steadily increased in recent decades, conflicting with the goal of keeping the mountain and the surrounding area as wilderness. The number of registered visitors at trailheads in the High Peaks Wilderness increased from 57,016 in 1988 to 139,663 in 1998, prompting the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation to formulate the High Peaks Unit Management Plan in March 1999.[32][33] A 2021 study by Otak observed significant crowds on the summit of the mountain on popular summer days.[34]

Routes

editThe shortest and most frequently used route up the mountain is from the northwest on the Van Hoevenberg Trail. The trail starts at the Adirondak Loj near Heart Lake and proceeds 7.4 miles (11.9 km) to the summit. Marcy Dam is located on the route 2.3 miles (3.7 km) from the trailhead along with campsites. This route involves a gain of 3,166 feet (965 m) in elevation from the trailhead to summit. Portions of the trail can be used for alpine skiing in the winter.[35]

A second ascent route approaches from the northeast, via the Phelps Trail in Johns Brook Valley, which merges with the Van Hoevenberg Trail shortly before the peak. Beginning at the Garden parking lot in Keene Valley, this route is 9.1 miles (14.6 km) to the summit. The Johns Brook Lodge, the closest lodging to the mountain, is located 3.5 miles (5.6 km) from the trailhead. This route involves a gain of 3,821 feet (1,165 m) in elevation.[36] The mountain can also be ascended at the end of the Great Range Trail, which begins at the Rooster Comb trailhead in Keene Valley. This route is much more challenging and crosses the summits of the Great Range before merging with the Van Hoevenberg Trail, for a total distance of 14.5 miles (23.3 km) one way and 9,000 feet (2,700 m) of cumulative elevation gain.[37]

A lengthier southern approach can be made from the Upper Works trailhead via the Calamity Brook Trail. The route passes Lake Colden and Lake Tear of the Clouds on the way to the summit, and can also be used for skiing in the winter. This approach is 10.3 miles (16.6 km) to the summit and there several campsites along the route.[38] Less commonly, a southern approach can be made from the Elk Lake parking lot on the Elk Lake-Marcy Trail. This trail crosses private land and is closed during the big-game hunting season. The route is 11.0 miles (17.7 km) to the summit and involves a gain of 4,200 feet (1,300 m) of elevation.[39] A lean-to is available for camping at Panther Gorge, located 8.7 miles (14.0 km) from the trailhead. The two southern routes meet at the Four Corners intersection at the col between Mounts Marcy and Skylight, from which both peaks can be accessed.[39]

On clear days, 43 of the other 45 High Peaks are visible from the peak of Marcy.[20] Lake Champlain can be seen to the east,[40] and Mount Royal in Quebec can be seen to the north, 65 miles (105 km) away.[20]

Climate

editMount Marcy has a warm-summer humid continental climate (Dfb) as defined by the Köppen climate classification system, closely bordering on subarctic.

| Climate data for Mount Marcy, 1991–2020 normals (elevation 4,642 ft (1,415 m)), 1981–2018 extremes (elevation 3,825 ft (1,166 m)) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 54.3 (12.4) |

55.0 (12.8) |

70.5 (21.4) |

80.8 (27.1) |

82.8 (28.2) |

84.2 (29.0) |

85.4 (29.7) |

85.7 (29.8) |

84.6 (29.2) |

74.6 (23.7) |

62.9 (17.2) |

57.1 (13.9) |

85.7 (29.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 18.1 (−7.7) |

19.6 (−6.9) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

42.2 (5.7) |

54.5 (12.5) |

63.0 (17.2) |

67.2 (19.6) |

66.0 (18.9) |

60.5 (15.8) |

47.9 (8.8) |

32.6 (0.3) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

43.5 (6.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 10.1 (−12.2) |

11.5 (−11.4) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

32.4 (0.2) |

44.9 (7.2) |

54.1 (12.3) |

58.7 (14.8) |

57.4 (14.1) |

51.5 (10.8) |

39.4 (4.1) |

26.1 (−3.3) |

16.5 (−8.6) |

35.1 (1.7) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 2.1 (−16.6) |

3.4 (−15.9) |

11.2 (−11.6) |

22.7 (−5.2) |

35.4 (1.9) |

45.1 (7.3) |

50.1 (10.1) |

48.8 (9.3) |

42.5 (5.8) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

19.7 (−6.8) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

26.8 (−2.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −36.0 (−37.8) |

−32.0 (−35.6) |

−28.7 (−33.7) |

−3.5 (−19.7) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

22.4 (−5.3) |

31.9 (−0.1) |

29.6 (−1.3) |

20.3 (−6.5) |

10.5 (−11.9) |

−14.4 (−25.8) |

−29.7 (−34.3) |

−36.0 (−37.8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.20 (132) |

4.01 (102) |

5.40 (137) |

6.52 (166) |

7.01 (178) |

7.68 (195) |

7.38 (187) |

7.13 (181) |

6.68 (170) |

7.71 (196) |

6.30 (160) |

6.16 (156) |

77.18 (1,960) |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 6.2 (−14.3) |

6.7 (−14.1) |

12.6 (−10.8) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

46.1 (7.8) |

51.2 (10.7) |

50.7 (10.4) |

44.6 (7.0) |

32.3 (0.2) |

21.1 (−6.1) |

13.0 (−10.6) |

28.3 (−2.1) |

| Source: PRISM[41] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

editFlora

editThe lower slopes of Mount Marcy are covered by hardwood forests containing American beech, sugar maple, and yellow birch trees. The upper slopes contain balsam fir and red spruce. Above an elevation of 4,200 feet (1,300 m), only the balsam fir grows.[42] The cold and windy climate near the summit creates a krummholz zone with short, crooked trees and large areas of exposed rock where no plants can take root, although lichens will grow on the rocks.[43]

About 18 acres (7.3 hectares) near the summit is covered by alpine tundra vegetation where trees cannot grow,[44] a remnant of the tundra ecosystem which covered the entire region at the end of the last ice age and retreated uphill as the climate warmed.[42] This small ecosystem is primarily covered by sphagnum moss and is home to other alpine plants, including alpine bilberry, cottongrass, Labrador tea, Lapland rosebay, and leatherleaf. Botanist Edwin Ketchledge conducted an ecological study of the summits in the late 1960s and concluded the alpine plants were being destroyed by litter and trampling from hikers, after which habitat restoration projects were carried out in the 1970s. The Summit Steward program was established to educate hikers against wandering off the trails and to mark the trails to the summit with cairns.[44] A long term study between 1957 and 1981 found that away from the hiking trails and direct human impact, the alpine ecosystem was stable over long periods of time.[45]

Fauna

editA variety of birds can be found in the spruce-fir forests of the upper slopes, including black-backed woodpeckers, golden-crowned kinglets, and white-winged crossbills, as well as mammals such as pine martens, porcupines, and red squirrels.[46] Despite the harsh climate, the summit of Marcy is still home to many animals. Birds that frequent the alpine zone of the High Peaks include common ravens, dark-eyed juncos, white-throated sparrows, winter wrens, and several species of warbler.[47] Mammals that live in the alpine zone include American ermines, long-tailed shrews, and snowshoe hares. The alpine meadows support pollinating insects, and bees, butterflies, flies, and wasps can be found in the summer.[48] Several species of leafhopper have been identified, some of which are endemic to alpine environments.[49]

Gallery

edit-

Mount Marcy seen from Mount Haystack, looking across Panther Gorge

-

Summit of Mount Marcy seen from near Mount Skylight

-

Mount Marcy summit

-

A historical plaque at the peak

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c Other members of the party included his son Ebenezer Emmons Jr., scientist William Charles Redfield, assistant state geologist James Hall, artist Charles C. Ingham, state botanist John Torrey, businessman David Henderson, guides John Cheney and Harvey Holt, and three unknown guides.[21] Previous ascents may have been made by Indigenous Americans but have not been recorded.[22]

- ^ Russell Carson and Arthur C. Parker concluded that Hoffman had pulled the name Tahawus, along with other Seneca terms, from an 1827 book titled An Account of Sundry Missions Performed Among the Senecas and Munsees by Rev. Timothy Alden, President of Allegheny College, and applied them to various Adirondack locations.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b c "The NGS Data Sheet". National GeodeticSurvey's Integrated Database. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- ^ "Highest and Lowest Elevations". United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ "The Peaks – Adirondack 46ers". adk46er.org. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ Anania, Billie (August 11, 2020). "What Would It Look Like to Decolonize Cartography? A Volunteer Group Has Ideas". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on November 28, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2024. See map "Haudenosaunee Country in Mohawk" by Karonhí:io Delaronde and Jordan Engel.

- ^ Weber 2001, p. 43.

- ^ Prince, J. Dyneley (1900). "Some Forgotten Indian Place-Names in the Adirondacks". The Journal of American Folklore. 13 (49): 123–128. doi:10.2307/533802. JSTOR 533802. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- ^ Weber 2001, p. 36.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 40–44.

- ^ Carson 1927, pp. 57–60.

- ^ "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. April 29, 2005. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2009.

- ^ Goodwin 2004, p. 269.

- ^ "High Peaks Wilderness Complex". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Sasso, John Jr. (2018). "Rise of the Adirondack High Peaks: The Story of the Inception of the Adirondack Forty-Six by Robert Marshall, George Marshall, and Russell M.L. Carson". Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies. 22 (1): 96–100.

- ^ Weber 2001, p. 95.

- ^ Waterman 2003, p. 175.

- ^ Mackenzie, Kevin B. (2016). "Adirondack Landslides: History, Exposures, and Climbing". Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies. 21 (1): 167–183. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ Weber 2001, p. 14.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c Groom, Debra J. (August 19, 2012). "First reported trek up Mount Marcy occurred 175 years ago". The Post-Standard. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Weber 2001, p. 29.

- ^ Weber 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Waterman 2003, pp. 116, 118.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Weber 2001, p. 90.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 131–132.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 133–135.

- ^ "Roosevelt-Marcy Trail". New York State Department of Transportation. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- ^ Weber 2001, pp. 206–207.

- ^ "High Peaks Wilderness Complex Unit Management Plan" (PDF). New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. March 1999. p. 47. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2024. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "Adirondack High Peaks Wilderness Visitor Use Management Study Final Report" (PDF). adirondackcouncil.org. Otak. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 12, 2024. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ Goodwin 2004, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Goodwin 2004, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Goodwin 2004, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Goodwin 2004, pp. 220–224.

- ^ a b Goodwin 2004, pp. 211–214.

- ^ Youker, Darrin (August 15, 2004). "Peak Performance". The Post-Star. pp. A1, A5. Retrieved March 12, 2024.

- ^ "PRISM Climate Group, Oregon State University". Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Weber 2001, p. 15.

- ^ Slack 2006, pp. 33–35.

- ^ a b Weber 2001, pp. 202–205.

- ^ Ketchledge, E. H.; Leonard, R. E. (October 1984). "A 24—YEAR COMPARISON OF THE VEGETATION OF AN ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN SUMMIT". Rhodora. 86 (848): 439–444. JSTOR 23314079. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ^ Slack 2006, pp. 22–23, 29.

- ^ Slack 2006, p. 65.

- ^ Slack 2006, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Buys, John L. (1931). "Leafhoppers of Mt. Marcy and Mt. Macintyre, Essex Co., New York (Homoptera, Cicadellidæ)". Journal of the New York Entomological Society. 39 (2): 139–143. JSTOR 25004400. Retrieved March 19, 2024.

Bibliography

edit- Carson, Russell M. L. (1927). Peaks and People of the Adirondacks. Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 9781404751200.

- Goodwin, Tony, ed. (2004). Adirondack trails. High peaks region (13th ed.). Adirondack Mountain Club. ISBN 1931951055.

- Slack, Nancy (2006). Adirondack alpine summits : an ecological field guide. Lake George, New York: Adirondack Mountain Club. ISBN 9781931951180.

- Waterman, Laura (2003). Forest and crag : a history of hiking, trail blazing, and adventure in the Northeast mountains (First ed.). Boston: Appalachian Mountain Club Books. ISBN 0910146756.

- Weber, Sandra (2001). Mount Marcy : the high peak of New York. Fleischmanns, N.Y.: Purple Mountain Press. ISBN 1930098227.

External links

edit- "Mount Marcy". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- Backcountry information for trails to Mount Marcy

- Mount Marcy at lakeplacid.com

- Mount Marcy at Peakbagger.com

- Mount Marcy at summitpost.org