Moulin Rouge! (/ˌmuːlæ̃ ˈruːʒ/, French: [mulɛ̃ ʁuʒ][6]) is a 2001 jukebox musical romantic drama film directed, produced, and co-written by Baz Luhrmann. It follows a Scottish poet, Christian, who falls in love with the star of the Moulin Rouge, cabaret actress and courtesan, Satine. The film uses the musical setting of the Montmartre Quarter of Paris and is the final part of Luhrmann's Red Curtain Trilogy, following Strictly Ballroom (1992) and Romeo + Juliet (1996). A co-production of Australia and the United States, it features an ensemble cast starring Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor, with Jim Broadbent, Richard Roxburgh, John Leguizamo, Jacek Koman, and Caroline O'Connor in supporting roles.

| Moulin Rouge! | |

|---|---|

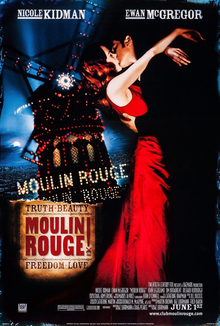

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Baz Luhrmann |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Donald M. McAlpine |

| Edited by | Jill Bilcock |

| Music by | Craig Armstrong |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century Fox |

Release dates | |

Running time | 128 minutes[3] |

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $50 million[5] |

| Box office | $179.2 million[5] |

Moulin Rouge! premiered at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival, where it competed for the Palme d'Or[7] and was released in theaters on 25 May 2001 in Australia and on 1 June 2001 in North America. The film was praised for Luhrmann's direction, the performances of the cast, its soundtrack, costume design, and production values. It was also a commercial success, grossing $179.2 million on a $50 million budget. At the 74th Academy Awards, the film received eight nominations, including Best Picture, and won two (Best Production Design and Best Costume Design). Later critical reception for Moulin Rouge! remained positive and has been considered by many to be one of the best films of all time, with it ranking 53rd in the BBC's 2016 poll of the 100 greatest films of the 21st century.[8][9] A stage musical adaptation premiered in 2018.

Plot

editIn 1900 in Paris, Christian, a young writer depressed about the recent death of the woman he loved, begins writing their story on his typewriter.

A year earlier in 1899, he arrives in the Montmartre district of Paris to join the Bohemian movement. He suddenly meets Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and his troupe of performers who are writing a play called Spectacular Spectacular. After Christian helps them complete the play, they go to the Moulin Rouge where they hope Christian's talents will impress Satine, the star performer and courtesan, who will in turn convince Harold Zidler, the proprietor of the Moulin Rouge, to let Christian write the show. However, Zidler plans to have the wealthy, powerful and unscrupulous Duke of Monroth sleep with Satine in exchange for potential financing to convert the club into a theater.

That night, Satine mistakes Christian for the Duke and attempts to seduce him by dancing with him before retiring to her private chamber with him to discuss things privately, but eventually Christian reveals his true identity. After the Duke interrupts them, Satine claims that the two of them and the Bohemians were rehearsing Spectacular Spectacular. Aided by Zidler, Christian and the Bohemians improvise a story for the Duke about a beautiful Indian courtesan who falls in love with a poor sitar player she mistook for an evil maharaja. Approving the story, the Duke agrees to invest, but only if Satine and the Moulin Rouge are turned over to him. Later, Satine claims not to be in love with Christian, but he eventually wears down her resolve and they kiss.

During construction at the Moulin Rouge, Christian and Satine's love deepens while the Duke becomes frustrated with all the time he thinks Satine is spending with Christian working on the play. To calm him, Zidler arranges for Satine to spend the night with the Duke and angrily tells her to end their affair. She misses the dinner when she falls unconscious, leading a doctor to diagnose a fatal case of consumption. She does try to end things by telling Christian that their relationship is endangering the production, but Christian writes a secret song to include in the show that affirms their unending, passionate love.

At the final rehearsal, Nini, a can-can dancer jealous of Satine's popularity, hints to the Duke that the play represents the relationship between him, Christian, and Satine. Enraged, the Duke demands that the show ends with the courtesan marrying the maharaja, instead of Christian's ending where she marries the sitar player. Satine promises to spend the night with him after which they will decide on the ending. Ultimately, she fails to seduce the Duke due to her feelings for Christian, and Le Chocolat, one of the cabaret dancers, saves her from the Duke's attempt to rape her. Christian decides that he and Satine should leave the show behind and run away to be together while the Duke vows to kill Christian.

Zidler finds Satine in her dressing room packing. He tells her that her illness is fatal, that the Duke is planning on murdering Christian, and that if she wants Christian to live, she must cut him off completely and be with the Duke. Mustering all her acting abilities, she complies, leaving Christian devastated.

On the opening night of the show, in front of a full audience, Christian denounces Satine and vows to give her to the Duke before walking off the stage, but Toulouse-Lautrec cries out from the rafters, "The greatest thing you'll ever learn is just to love and be loved in return." This spurs Satine to sing their secret song, causing Christian to change his mind. After Zidler and the company thwart several attempts by the Duke and his bodyguard to kill Christian, the show ends with Christian and Satine proclaiming their love as the Duke permanently storms out of the cabaret. The audience erupts in applause, but Satine collapses after the curtains close. Before dying, she tells Christian to write their story so she will always be with him.

In the present, the Moulin Rouge has closed down and is in disrepair; Zidler, the Duke, the Diamond Dogs, and the Bohemians are gone; and Christian finishes his and Satine's story, declaring their love will live forever.

Cast

edit- Nicole Kidman as Satine

- Ewan McGregor as Christian

- Jim Broadbent as Harold Zidler

- Richard Roxburgh as The Duke of Monroth

- John Leguizamo as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

- Jacek Koman as The Unconscious Argentinean[a]

- Caroline O'Connor as Nini Legs-In-the-Air

- Kerry Walker as Marie

- Lara Mulcahy as Môme Fromage

- Garry McDonald as The Doctor

- Matthew Whittet as Satie

- David Wenham as Audrey

- Kiruna Stamell as La Petite Princesse

- DeObia Oparei as Le Chocolat

- Kylie Minogue as The Green Fairy

- Ozzy Osbourne as the voice of The Green Fairy

- Peter Whitford as The Stage Manager

- Linal Haft as Warner

- Norman Kaye as Satine's Doctor

- Arthur Dignam as Christian's Father

- Carole Skinner as The Landlady

- Jonathan Hardy as The Man in the Moon

- Plácido Domingo as the voice of the Man in the Moon

- Keith Robinson as Le Pétomane

- Tara Morice as The Prostitute

- Sue-Ellen Shook as Baby Doll

- Kip Gamblin as Latin Dancer

Production

editWriting and inspiration

editMoulin Rouge! was influenced by an eclectic variety of comic and melodramatic musical sources, including the Hollywood musical, "vaudeville, cabaret culture, stage musicals, and operas." Its musical elements also allude to Luhrmann's earlier film Strictly Ballroom.[11]

Giacomo Puccini's opera La bohème, which Luhrmann directed at the Sydney Opera House in 1993, was a key source of the plot for Moulin Rouge!.[12] Further stylistic inspiration came from Luhrmann's encounter with Bollywood films during his visit to India while conducting research for his 1993 production of Benjamin Britten's opera A Midsummer Night's Dream.[13] According to Luhrmann:

. . . we went to this huge, ice cream picture palace to see a Bollywood movie. Here we were, with 2,000 Indians watching a film in Hindi, and there was the lowest possible comedy and then incredible drama and tragedy and then break out in songs. And it was three-and-a-half hours! We thought we had suddenly learnt Hindi, because we understood everything! We thought it was incredible. How involved the audience were. How uncool they were – how their coolness had been ripped aside and how they were united in this singular sharing of the story. The thrill of thinking, 'Could we ever do that in the West? Could we ever get past that cerebral cool and perceived cool.' It required this idea of comic-tragedy. Could you make those switches? Fine in Shakespeare – low comedy and then you die in five minutes. . . . In Moulin Rouge!, we went further. Our recognisable story, though Orphean in shape, is derived from Camille, La Boheme – whether you know those texts or not, you recognise those patterns and character types.[14]

In the DVD's audio commentary, Luhrmann revealed that he also drew from the Greek tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice. The filmmakers projected the Orpheus figure onto Christian by characterizing the latter as a musical genius whose talent surpassed that of everyone else in his world. The film's use of songs from the mid- to late 20th century in the 1899 setting makes Christian appear ahead of his time as a musician and writer. Moulin Rouge!′s plot also parallels that of the myth: "McGregor, as a poet who spouts deathless verse . . . , descends into a hellish underworld of prostitution and musical entertainment in order to retrieve Kidman, the singing courtesan who loves him but is enslaved to a diabolical duke. He rescues her but looks back and . . . cue Queen's 'The Show Must Go On.'"[15]

Commentators have also noted the similarities between the film's plot and those of the opera La Traviata[16] and Émile Zola's novel Nana.[17] Other cinematic elements appear to have been borrowed from the musical films Cabaret,[18] Folies Bergère de Paris, and Meet Me in St. Louis.[19]

The character of Satine was based on the French can-can dancer Jane Avril.[20] The character of Harold Zidler shares his last name with Charles Zidler, one of the owners of the real Moulin Rouge. Satie was loosely based on the French composers Erik Satie and Maurice Ravel. Môme Fromage, Le Pétomane, and Le Chocolat share their names with performers at the actual cabaret. Marlene Dietrich, Greta Garbo and Rita Hayworth were cited as inspirations for the film's "look."[19]

Development

editLeonardo DiCaprio, who worked with Luhrmann on Romeo + Juliet, auditioned for the role of Christian.[21] Ethan Hawke also read for the role.[22] Luhrmann also considered younger actors for the role, including Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal, before Ewan McGregor won the part. Courtney Love auditioned for the role of Satine and gave approval for "Smells Like Teen Spirit" to be used in the film.[23]

Filming

editProduction began on 9 November 1999 and was completed on 13 May 2000,[24][25] with a budget of $50 million.[5] It was shot on the sound stages at Fox Studios in Sydney.[26] Filming generally went smoothly, but Kidman broke her ribs twice when she was lifted into the air during the dance sequences. She also suffered from a torn knee cartilage resulting from a fall during the "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend" production song.[19] Kidman later stated in an interview with Graham Norton that she broke a rib while getting into a corset by tightening it as much as possible to achieve an 18-inch waist, and that she fell down the stairs while dancing in heels.[27] The production overran its shooting schedule and had to be out of the sound stages to make way for Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones (which also starred McGregor). This necessitated the filming of some pick-up shots in Madrid.[28][29]

In the liner notes to the film's Special Edition DVD, Luhrmann writes that "[the] whole stylistic premise has been to decode what the Moulin Rouge was to the audiences of 1899 and express that same thrill and excitement in a way to which contemporary movie-goers can relate."[30] Both Roger Ebert and The New York Times compared the film's editing and cinematography to that of a music video and noted its visual homage to early Technicolor films.[31][18]

Music

editMarsha Kinder describes Moulin Rouge! as a "brilliant," "celebratory," and "humorous" musical and aural pastiche due to its use of diverse songs.[32] Moulin Rouge! takes well-known popular music, mostly drawn from the MTV Generation, and juxtaposes it into a tale set in a turn-of-the-century Paris cabaret.[30] Kinder holds that keeping borrowed lyrics and melodies intact "makes it almost impossible for spectators to miss the poaching [of songs] (even if they cannot name the particular source)."[33]

The film uses so much popular music that it took Luhrmann two and a half years to secure the rights to all of the songs.[34] Some of the songs sampled include "Chamma Chamma" from the Hindi movie China Gate, Queen's "The Show Must Go On" (arranged in operatic format), David Bowie's rendition of Nat King Cole's "Nature Boy", "Lady Marmalade" by Labelle (in the Christina Aguilera/P!nk/Mýa/Lil' Kim cover commissioned for the film), Madonna's "Material Girl" and "Like a Virgin", Elton John's "Your Song", the titular number of The Sound of Music, "Roxanne" by The Police (in a tango format using the composition "Tanguera" by Mariano Mores), and "Smells Like Teen Spirit" by Nirvana.

Luhrmann had intended to incorporate songs by The Rolling Stones and Cat Stevens into the film, but could not obtain the necessary rights from these artists. When Stevens denied consent for the use of "Father and Son" due to religious objections to the film's content, "Nature Boy" was chosen as its replacement.[19]

Release and reception

editOriginally set for release on Christmas 2000, 20th Century Fox eventually moved the release of Moulin Rouge! to Summer 2001 to allow Luhrmann more time in post-production.[35][36] Moulin Rouge! premiered at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival on May 9, 2001, as the festival's opening title.[1]

Moulin Rouge! opened in the United States at two theaters in New York and Los Angeles on May 18, 2001.[1] It grossed US$167,540 on its opening weekend.[5][2] The film then expanded to a national release on June 1, 2001.[1] It generated $14.2 million, ranking in fourth place behind Pearl Harbor, Shrek and The Animal.[37] In the United Kingdom, Moulin Rouge! was the country's number one film for two weeks before being displaced by A.I. Artificial Intelligence.[38] During its fifth weekend, it reclaimed the number one spot.[39] The film remained so until it was dethroned by American Pie 2 in its sixth weekend.[40] Moulin Rouge! has grossed $57,386,369 in the United States and Canada and another $121,813,167 internationally[2] (including $26 million in the United Kingdom[41] and $3,878,504 in Australia[42]).

Moulin Rouge! received generally positive reviews from critics. Roger Ebert rated the film 3.5 stars out of 4, remarking that "the movie is all color and music, sound and motion, kinetic energy, broad strokes, operatic excess."[31] Newsweek praised McGregor's and Kidman's performances, stating that "both stars hurl themselves into the movie's reckless spirit, unafraid of looking foolish, adroitly attuned to Luhrmann's abrupt swings from farce to tragedy. (And both sing well.)"[43] The New York Times wrote that "the film is undeniably rousing, but there is not a single moment of organic excitement because Mr. Luhrmann is so busy splicing bits from other films" but conceded that "there's nothing else like it, and young audiences, especially girls, will feel as if they had found a movie that was calling them by name."[18] All Things Considered commented the film was "not gonna be for all tastes" and that "you either surrender to this sort of flamboyance or you experience it as overkill."[44][45]

Moulin Rouge! holds a rating of 66/100 at Metacritic based on 35 reviews.[46] At Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 75% "Fresh" approval rating based on 259 reviews, with an average score of 7.1/10. The website's critics' consensus reads: "A love-it-or-hate-it experience, Moulin Rouge is all style, all giddy, over-the-top spectacle. But it's also daring in its vision and wildly original."[47] In December 2001, the film was named the best film of the year by viewers of Film 2001.[48] Entertainment Weekly ranked it #6 on its list of the top ten movies of the decade, saying, "Baz Luhrmann's trippy pop culture pastiche from 2001 was an aesthetically arresting ode to poetry, passion, and Elton John. It was so good, we'll forgive him for Australia."[49][50] In 2008, Moulin Rouge! was ranked No. 211 on Empire's 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[51] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[52]

Home Theater Forum rated the DVD release of Moulin Rouge! as the best DVD of 2001.[53] Luhrmann had hand-picked the features and behind-the scenes footage for the two-disc DVD edition.[54]

Analysis

editPostmodern

editScholarly commentators have interpreted Moulin Rouge! as an exemplary postmodern film, citing its methods of aesthetic expression, symbolism, and ties to both fine art and pop culture as evidence.[55][56] The film's music also contributes to its postmodern aesthetic. Notably, Moulin Rouge! combines mid-to-late 20th Century melodies and lyrics with a narrative set in fin de siècle France.[33] The use of famous popular songs in a new, original context requires audiences to reinterpret their significance within the framework of the narrative and challenge the assumption that music's symbolism is static.[57][58]

Moulin Rouge! also makes ample use of other postmodern filmmaking techniques, including fragmentation and juxtaposition. As the film's protagonist, Christian is the primary source of Moulin Rouge!'s story line and many portions of the story are told from his point of view. However, the narrative is fragmented on several occasions when the film deviates from Christian's perspective or integrates a flashback. Moulin Rouge! also juxtaposes a play-within-a-film (Spectacular Spectacular) with the film's events themselves to draw parallels between the plot of the play and the characters' lives. This culminates in the "Come What May" sequence, which reveals the development of Christian and Satine's relationship alongside the progression of Spectacular Spectacular's rehearsals.[59]

Postmodernism is also evident in Moulin Rouge!'s homage to Western musicals, Bollywood masala films, and music videos, as well as Luhrmann's film Strictly Ballroom.[60]

Feminist critique

editIt has been argued that, despite the film's postmodern stylings, Moulin Rouge! is not a feminist text because the death of its female protagonist (Satine) serves as a plot device that upholds patriarchical perspectives in storytelling.[61]

Accolades

editMoulin Rouge! received eight Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture and Best Actress (Nicole Kidman), winning in two categories for Best Art Direction and Best Costume Design. It became the first musical film to receive a coveted Best Picture nomination since Beauty and the Beast (1991).[62] Despite the film's overwhelming success, Baz Luhrmann was notably excluded from the Best Director lineup; commenting on this during the Oscar ceremony, host Whoopi Goldberg remarked, "I guess Moulin Rouge! just directed itself."[63] Additionally, the only original tune in the film, "Come What May" was disqualified from the Best Original Song consideration because it was originally intended, although unused, for Luhrmann's previous film Romeo + Juliet and not written expressly for Moulin Rouge!.[64] It tied with The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring for leading twelve nominations at the 55th British Academy Film Awards and resulted in three wins, including Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Jim Broadbent).[65] The musical also led the 59th Golden Globe Awards, alongside the drama A Beautiful Mind, each receiving six nominations; it won three, including Best Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy.[66]

Other notable ceremonies where it received much recognition included the American Film Institute Awards, the Australian Film Institute Awards, and the Satellite Awards. Various prestigious award bodies, such as the National Board of Review and the PGA Awards named it the best film of the year.

American Film Institute recognition

Soundtrack

editMusical numbers

edit- "Nature Boy" – Toulouse

- "Complainte de la Butte/Children of the Revolution"

- "The Sound of Music" – Toulouse, Christian, and Satie

- "Green Fairy Medley" (The Sound of Music/Children of the Revolution/Nature Boy) – Christian, The Bohemians, and the Green Fairy

- "Zidler's Rap Medley" (Lady Marmalade/Zidler's Rap/Because We Can/Smells Like Teen Spirit) – Zidler, Moulin Rouge Dancers, Christian and Patrons

- "Sparkling Diamonds" (Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend/Material Girl) – Satine and Moulin Rouge Dancers

- "Rhythm of the Night" – Moulin Rouge Dancers

- "Sparkling Diamonds" (Reprise) – Satine

- "Meet Me in the Red Room"

- "Your Song" – Christian

- "Your Song" (Reprise) – Satine

- "The Pitch" - Spectacular Spectacular – Zidler, Christian, Satine, The Duke, and Bohemians

- "One Day I'll Fly Away" – Satine and Christian

- "Elephant Love Medley" – Christian and Satine

- "Górecki" – Satine

- "Like a Virgin" – Zidler, The Duke, and Chorus Boys

- "Come What May" – Christian, Satine, the Argentinean and Cast of Spectacular Spectacular

- "El Tango de Roxanne" – The Argentinean, Christian, Satine, The Duke, and Moulin Rouge Dancers

- "Fool to Believe" – Satine

- "One Day I'll Fly Away" (Reprise) – Satine and Zidler

- "The Show Must Go On" – Zidler, Satine, and Moulin Rouge Stagehands

- "Hindi Sad Diamonds" (Chamma Chamma/Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend) – Toulouse, Nini Legs-in-the-Air, Satine, and the Cast of Spectacular Spectacular

- "Come What May" (Reprise) – Satine and Christian

- "Coup d'État"/"Finale" (The Show Must Go On/Children of the Revolution/Your Song/One Day I'll Fly Away/Come What May) – Christian, Satine, and Cast of Spectacular Spectacular

- "Nature Boy" (Reprise) – Toulouse and Christian

Music sources

- "Nature Boy" – Nat King Cole, covered by David Bowie and remixed by Massive Attack for the soundtrack.

- "The Sound of Music" – Mary Martin (and later by Julie Andrews) (from the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical of the same name, featuring overdubbed theremin played by Bruce Woolley)

- "The Lonely Goatherd" – also from The Sound of Music (but heard as instrumental)

- "Lady Marmalade" – Labelle, covered for the film by Christina Aguilera, Lil' Kim, Mýa, Missy Elliott, and Pink.

- "Because We Can" – Fatboy Slim

- "Complainte de la Butte" – Georges Van Parys and Jean Renoir covered by Rufus Wainwright

- "Rhythm of the Night" – DeBarge

- "Material Girl" – Madonna

- "Smells Like Teen Spirit" – Nirvana

- "Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend" – Introduced by Carol Channing, made popular by Marilyn Monroe.

- "Diamond Dogs" – David Bowie covered for the film by Beck.

- "Galop Infernal (Can-can)" – Jacques Offenbach (tune for Spectacular, Spectacular)

- "One Day I'll Fly Away" – Randy Crawford

- "Children of the Revolution" – T.Rex (Covered by Bono, Gavin Friday, Violent Femmes, and Maurice Seezer)

- "Gorecki" – Lamb

- "Come What May" – Ewan McGregor and Nicole Kidman (written by David Baerwald)

- "Roxanne" – The Police (Title in film: "El Tango de Roxanne", combined with music "Tanguera" by Mariano Mores)

- "Tanguera" – Mariano Mores (Title in film: "El Tango de Roxanne", combined with music "Roxanne" by The Police)

- "The Show Must Go On" – Queen

- "Like a Virgin" – Madonna

- "Your Song" – Elton John

- "Chamma Chamma" – Alka Yagnik (Incorporated in the film song titled "Hindi Sad Diamonds"; originally performed by Alka Yagnik in the 1998 Hindi film China Gate, composed by Anu Malik).

Elephant Love Medley

- "Love Is Like Oxygen" by Sweet – Andy Scott and Trevor Griffin

- "Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing" by The Four Aces – Sammy Fain and Paul Francis Webster

- "All You Need Is Love" by The Beatles – John Lennon and Paul McCartney

- "I Was Made for Lovin' You" by Kiss – Desmond Child, Paul Stanley, Vini Poncia

- "One More Night" by Phil Collins – Phil Collins

- "In the Name of Love" by U2 – U2

- "Don't Leave Me This Way" by Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes and later Thelma Houston – Kenneth Gamble, Leon Huff, and Cary Gilbert

- "Silly Love Songs" by Wings – Paul McCartney

- "Up Where We Belong" by Joe Cocker and Jennifer Warnes – Jack Nitzsche and Buffy Sainte-Marie

- "Heroes" by David Bowie – David Bowie

- "I Will Always Love You" by Dolly Parton and later Whitney Houston – Dolly Parton

- "Your Song" by Elton John – Elton John and Bernie Taupin

Jamie Allen contributes additional vocals to the "Elephant Love Medley".[79] "Love Is Like Oxygen" and "Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing" are only spoken dialogue; they are not actually sung in the medley.

"Your Song" is performed by Ewan McGregor and Alessandro Safina, who contributes additional lyrics in Italian.[79]

Two soundtrack albums were released, with the second coming after the first one's massive success. The first volume featured the smash hit single "Lady Marmalade", performed by Christina Aguilera, Lil' Kim, Mýa and Pink. The first soundtrack, Moulin Rouge! Music from Baz Luhrmann's Film, was released on 8 May 2001,[80] with the second, Moulin Rouge! Music from Baz Luhrmann's Film, Vol. 2, following on 26 February 2002.[81]

Stage adaptation

editAs early as November 2002, Luhrmann revealed that he intended to adapt Moulin Rouge! into a stage musical. A Las Vegas casino was the reputed site of the proposed show.[82] Luhrmann was said to have asked both Kidman and McGregor to reprise their starring roles in the potential stage version.[83]

In 2008, a stage adaptation entitled La Belle Bizarre du Moulin Rouge ("The Bizarre Beauty of the Moulin Rouge") toured Germany and produced a cast recording.[84]

In 2016, it was announced that Global Creatures was developing Moulin Rouge! into a stage musical. Alex Timbers was slated to direct the production, and John Logan was tapped to write the book.[85] Moulin Rouge!: The Musical, starring Aaron Tveit as Christian and Karen Olivo as Satine, premiered on 10 July 2018 at the Colonial Theatre in Boston.[86] The Broadway production opened at the Al Hirschfeld Theatre on 25 July 2019.[87] In February 2024, Boy George, Derek Klena, and Courtney Reed were playing the roles of Zidler, Christian, and Satine, respectively.[88]

In popular culture

editThe 2002 made-for-television movie, It's a Very Merry Muppet Christmas Movie, features a Christmas-themed parody entitled "Moulin Scrooge", in which various scenes and musical numbers are re-enacted by Muppets.[89] In Moulin Scrooge, Christian is played by Kermit the Frog, Satine (named Saltine) by Miss Piggy, Toulouse-Lautrec by Gonzo and Zidler by Fozzie Bear.[90]

The music video for Mr. Brightside was inspired by the film.[91]

In the 2017–18 figure skating season, at the 2018 Winter Olympics, Canadian skaters Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir performed two selections from Moulin Rouge!, interpreting the story of Christian and Satine through "The Show Must Go On", "El Tango de Roxanne", and "Come What May". Their performance won the gold medal in the team and the individual events.[92] At this event, Virtue and Moir became the most decorated skaters of all time.[93]

See also

edit- Moulin Rouge, 1928 film

- Moulin Rouge, 1952 film

Notes

edit- ^ Though this character does not spend his entire time on screen unconscious and instead displays symptoms that are more closely associated with narcolepsy, the film and its credits refer to this character as The Unconscious Argentinean.[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e Farache, Emily (21 March 2001). "'Moulin Rouge' Does Cannes-Cannes". E! Online. Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ^ a b c "Moulin Rouge (2001) [Summary]". The Numbers. 2021. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "MOULIN ROUGE". British Board of Film Classification. n.d. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Moulin Rouge!". bfi. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Moulin Rouge!". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ a b "Official Selection 2001: All the Selection". Festival De Cannes. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- ^ "The 21st century's 100 greatest films". BBC. 23 August 2016. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". Variety. 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge!". IMDb. Archived from the original on 24 April 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ Kinder, Marsha (Spring 2002). "Moulin Rouge". Film Quarterly. 55 (3): 52–53. doi:10.1525/fq.2002.55.3.52. ISSN 0015-1386.

- ^ Conner Bennett, Kathryn (2004). "The gender politics of death: Three formulations of La Bohème in contemporary cinema". Journal of Popular Film and Television. 32 (3): 114. doi:10.1080/01956051.2004.10662056. ISSN 1930-6458. S2CID 154025769.

- ^ Lee, Janet W. (28 October 2020). "How a Bollywood film inspired Baz Luhrmann to bring 'Moulin Rouge' to Broadway". Yahoo! Entertainment. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Andrew, Geoff (7 September 2001). "Baz Luhrmann (I)". Guardian interviews at the BFI. The Guardian. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ Green, Jesse (13 May 2001). "How do you make a movie sing?". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ "La traviata in pop culture". Discover opera. English National Opera. n.d. Archived from the original on 30 September 2020. Retrieved 15 January 2021.

- ^ Magedanz, Stacy (2006). "Allusion as form: The Waste Land and Moulin Rouge!". Orbis Litterarum. 62 (2): 160. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0730.2006.00853.x. S2CID 170576709. Archived from the original on 9 August 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ a b c Mitchell, Elvis (18 May 2001). "An eyeful, an earful, an anachronism: Lautrec meets Lady Marmalade". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Moulin Rouge!". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. American Film Institute. n.d. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- ^ Levy, Paul (17 June 2011). "The artistry of Toulouse-Lautrec and his dancing muse Jane Avril". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 August 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ^ Gray, Tim (11 February 2014). "Leonardo DiCaprio unleashes a fearless 'Wolf' performance". Variety. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ^ "Ethan Hawke Recalls Losing Beloved Role to Ewan McGregor". Screen Rant. 16 September 2022.

- ^ Warner, Kara (2 May 2011). "'Moulin Rouge' could have starred Heath Ledger, Baz Luhrmann reveals". MTV News. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge!".

- ^ "Moulin Rouge! (2001) Filming & production". IMDb. n.d. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- ^ Yee, Hannah-Rose (6 May 2021). "How Moulin Rouge broke every rule of filmmaking—and became a cinematic icon". Vogue. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "Nicole Kidman: 'I broke my rib getting into corset for Moulin Rouge'". news.com.au. News Corp Australia. 28 November 2014. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Brod, Doug; Grisolia, Cynthia, eds. (27 April 2001). "May summer movie preview: Moulin Rouge". Entertainment Weekly. No. 593. p. 43. ISSN 1049-0434.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge". Entertainment Weekly. 17 March 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ a b Liner notes, Special Edition DVD

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (1 June 2001). "Moulin Rouge". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2013. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ Kinder 2002, pp. 52 & 54.

- ^ a b Kinder 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (18 May 2001). "Tripping the light". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

- ^ Fuson, Brian (5 October 2000). "No post haste: 'Moulin Rouge' pushed back". Hollywood Reporter. p. 4.

- ^ Snow, Shauna (5 October 2000). "Morning report: Entertainment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- ^ Linder, Brian (5 June 2001). "Weekend Box Office: Harbor Withstands Shrek Attack". Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "A.I. tops UK box office chart".

- ^ "Moulin Rouge regains UK box office crown".

- ^ "UK welcomes second helping of Pie".

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (25 December 2001). "Homegrown pix gain in Europe". Variety. Archived from the original on 3 May 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge (2001) [International]". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Ansen, David (27 May 2001). "Yes, 'Rouge' can, can can". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 10 April 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Review: Movie 'Moulin Rouge'". Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints. Gale. 18 May 2001.

- ^ "'Moulin Rouge'". All Things Considered. NPR. 18 May 2001. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge!". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge is viewers' favourite". BBC News. 20 December 2001. Archived from the original on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ^ Geier, Thom; Jensen, Jeff; Jordan, Tina; Lyons, Margaret; Markovitz, Adam; Nashawaty, Chris; Pastorek, Whitney; Rice, Lynette; Rottenberg, Josh; Schwartz, Missy; Slezak, Michael; Snierson, Dan; Stack, Tim; Stroup, Kate; Tucker, Ken; Vary, Adam B.; Vozick-Levinson, Simon; Ward, Kate (11 December 2009). "The 100 greatest movies, TV shows, albums, books, characters, scenes, episodes, songs, dresses, music videos, and trends that entertained us over the past 10 years". Entertainment Weekly. No. 1079/1080. pp. 74–84.

- ^ "100 greatest movies, TV shows, and more". Entertainment Weekly. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ "Empire's 500 greatest movies of all time". Cinema Realm. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "CinemaScore [Home page]". CinemaScore. Retrieved 21 May 2021.

- ^ Rivero, Enrique (27 December 2001). "HTF taps Moulin Rouge as year's best DVD". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on 5 January 2002. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Sherber, Anne (14 December 2001). "Moulin Rouge director shares experiences on DVD". hive4media.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2002. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Conner Bennett 2004, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Yang, Mina (November 2008). "Moulin Rouge! and the undoing of opera". Cambridge Opera Journal. 20 (3): 269. doi:10.1017/S095458670999005X. ISSN 1474-0621. S2CID 194085131.

- ^ Conner Bennett 2004, p. 114.

- ^ Kinder 2002, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Conner Bennett 2004, p. 115.

- ^ Kinder 2002, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Conner Bennett 2004, p. 111.

- ^ "Oscar Honors "Moulin Rouge" and Boheme Designer Catherine Martin". Playbill. 24 March 2002. Archived from the original on 3 October 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Krygger, Cassidy (11 March 2020). "There's Something About Baz". Ponderings.

- ^ Bonin, Liane (20 December 2001). "Ewan and Nicole won't sing at the Oscars". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "'MOULIN ROUGE' AND 'LORD OF THE RINGS' LEAD BAFTA NOMINATIONS". HELLO!. 28 January 2002. Archived from the original on 21 August 2023. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "A Beautiful Mind, Moulin Rouge Lead Golden Globe Nominations". Fox News. 20 January 2002. Archived from the original on 23 June 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "The 74th Academy Awards (2002) Winners & Nominees". oscars.org. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. n.d. Archived from the original on 9 November 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "AACTA Awards [2001]". Australian Academy of Cinema and Television Arts. n.d. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Feiwell, Jill (24 February 2002). "Cuts above the rest". Variety. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "The 55th British Academy Film Awards (2002) Nominees and Winners". British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA). Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2023.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge!". www.goldenglobes.com. n.d. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "Complete List Of Grammy Nominees". CBS News. 4 January 2002. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "'Moulin Rouge' is NBR's top film of 2001". United Press International. 5 December 2001. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Welkos, Robert (4 March 2002). "Producers honor 'Moulin Rouge'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d "'Rouge' rocks kudos: Luhrmann tuner takes 8 golden satellites". Variety. 22 January 2002. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Berkshire, Geoff (18 December 2001). "'Moulin Rouge' in orbit, topping Satellite noms". Variety. Archived from the original on 10 January 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ "AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ a b Various artists (2001). Moulin Rouge! Music from Baz Luhrmann's Film (Booklet). Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation / Interscope Records.

- ^ Kohlenstein, Brad (n.d.). "Moulin Rouge [Original Motion Picture Soundtrack] [Review]". AllMusic. AllMusic, Netaktion LLC.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (n.d.). "Moulin Rouge, Vol. 2 [Review]". AllMusic. AllMusic, Netaktion LLC.

- ^ Jones, Kenneth (10 December 2002). "Stage version of Luhrmann's "Moulin Rouge" aimed at a casino". Playbill. Archived from the original on 9 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Gorgan, Elena (20 June 2006). "Moulin Rouge on the stage?". Softpedia. Archived from the original on 14 November 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ "La Belle Bizarre Du Moulin Rouge » German Tour Cast". n.d. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2011.

- ^ Lang, Brent (1 September 2016). "'Moulin Rouge!' being developed into a stage musical". Variety. Archived from the original on 2 September 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ Wontorek, Paul (10 July 2018). "Exclusive! Karen Olivo and Aaron Tveit are ready for the high romance, drama (and laughs!) of Moulin Rouge!: The Musical". broadway.com. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ward, Maria (26 July 2019). "Moulin Rouge! premieres on Broadway with a spectacularly splashy opening night". Vogue. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ "Moulin Rouge! The Musical". Moulin Rouge! The Musical. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Bricken, Rob (30 November 2022). "It's a Very Merry Muppet Christmas Movie Is the Maddest Muppet Special Ever". Gizmodo AU. Archived from the original on 15 December 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2023.

- ^ "Moulin Scrooge - It's a Very Merry Muppet Christmas Movie - TUNE" (video). YouTube. TUNE - Musical Momements. 14 December 2021.

- ^ Smith, Sophie (29 April 2020). "Watch The Killers Break Down The 'Mr Brightside' Video". uDiscover Music. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ Willman, Chris (24 February 2018). "Olympic figure skating revives 'Moulin Rouge' and Baz Luhrmann is loving it". Variety. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ Yahoo Sports Staff (19 February 2018). "Most decorated figure skaters in Olympic history". Yahoo! Sports. Archived from the original on 22 February 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

External links

edit- Official website

- Moulin Rouge! at IMDb

- Moulin Rouge! at AllMovie

- Moulin Rouge! at the TCM Movie Database

- Moulin Rouge! at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- Moulin Rouge! at Box Office Mojo

- Moulin Rouge! at Metacritic

- Moulin Rouge! at Rotten Tomatoes

- Moulin Rouge! Archived 26 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine at Oz Movies