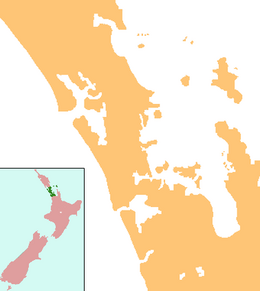

Motukorea or Browns Island is a small New Zealand island, in the Hauraki Gulf north of Musick Point, one of the best preserved volcanoes in the Auckland volcanic field. The age of eruption is about 25,000 years ago, when the Tāmaki Estuary and the Waitemata Harbour were forested river valleys.[1] Due to centuries of cultivation, little native bush remains except on the north-eastern cliffs, leaving the volcanic landforms easily visible. It exhibits the landforms from three styles of eruption. The island consists of one main scoria cone with a deep crater, a small remnant arc of the tuff ring forming the cliffs in the northeast, and the upper portions of lava flows. The area was dry land when the eruptions occurred, but much of the lava is now submerged beneath the sea. 36°49′50″S 174°53′41″E / 36.8306°S 174.8948°E

Motukorea (Māori) | |

|---|---|

View of Bucklands Beach, Motukorea (centre) and Rangitoto Island in the background. | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Hauraki Gulf |

| Coordinates | 36°49′50″S 174°53′41″E / 36.8306°S 174.8948°E |

| Highest elevation | 68 m (223 ft) |

| Administration | |

New Zealand | |

Geology

editMotukorea erupted approximately 24,500 years ago.[2] It began life with a series of wet explosive eruptions that cleared it of any debris and created a 1-kilometre shallow crater, as seen today. The ejected magma, together with large amounts of ash, accumulated around the crater to form a tuff ring. At the time of the eruption, the wind was probably blowing from a southwesterly direction, and a more substantial rim built up on the downward side. Interestingly, fossils of the now Australia-based Sydney mud cockle (Anadara trapezia) have been found amongst shell beds deposited from the volcano.[3]

After dry, fire-fountaining eruptions built the several scoria cones around the main crater, the sea rapidly eroded the tuff on the northern side of the island, and together with shell deposited the extensive flats on the south and west of the cone. A shallow reef extends 200m offshore.

During the Last Glacial Maximum, sea levels around Motukorea dropped to 100 metres lower than present day levels, meaning Motukorea was surrounded by a vast coastal plain where the Hauraki Gulf / Tīkapa Moana exists today, a part of the forested river valley of the Waitematā (now the Waitematā Harbour. Sea levels began to rise 7,000 years ago, after which Motukorea became an island separated from the rest of New Zealand.[4][3]

History

editMaori occupation

editThe history of Motukorea prior to European arrival is not well documented, and while many of the sources available speculate as to the origins of Ngāti Tamaterā mana whenua and their right to sell the island in 1840, few dispute it. Phillips makes mention of the Tainui canoe stopping at the island after leaving Wakatiwai on the Firth of Thames, before proceeding to Rangitoto where she met up with the Arawa canoe.[5]

In the intervening years, the general area came to be controlled by Ngāti Paoa and the lands to the west were controlled by Ngāti Whātua, but the island remained under the control of Ngāti Tamaterā. Opinion is divided as to why this may be, Phillips postulates that mana may have been vested in return for assistance in battle,[6] whereas Monin regards the occupation and sale of Motukorea as evidence of more widespread penetration of the inner Gulf by numerous Hauraki iwi and hapu.[7]

Motukorea's location at the mouth of the Tāmaki River was certainly important as it effectively controlled access up the river, and as a result Te Tō Waka (the Ōtāhuhu portage) and nearby Karetu portage through to the Manukau Harbour. The archaeological remains suggest Motukorea was intensively occupied in pre-European times, with people engaged in stone working industry, marine exploitation, gardening of the fertile volcanic soils, and establishing open and defended settlements. Three pā sites have been identified by Simmons.[citation needed] ‘Archaic’ type artifacts found on the island include worked moa bone, and one-piece fishhooks. Exotic stone resources including chert, basalt, argillite and obsidian from both local gulf island sources and as far afield as Coromandel Peninsula and Great Barrier Island.[8] The name Motukorea means "Oystercatcher Island".[3]

Brown & Campbell

editStarting from 1820, early European visitors included Richard Cruise, Samuel Marsden and John Butler, who both traded with Maori for produce. Dumont D’Urville visited the island in 1827 and reported it abandoned, probably on account of the musket wars.[9][10][11] Being already abandoned by Ngāti Tamaterā and located a considerable distance from where they were based in Coromandel, Te Kanini of Ngāti Tamaterā and the sub-chiefs Katikati and Ngatai were willing to sell Motukorea when William Brown and Logan Campbell indicated a desire to buy the island on 22 May 1840. Brown and Campbell settled on the western side of the island from 13 August 1840, making it one of the earliest European settlements in the Auckland area.[12] They built a raupo whare and ran pigs on the island, using it as a base from which they aspired to establish and supply the town of Auckland as soon as land was available on the isthmus.[13]

Not long after Brown and Campbell had taken up residence on the island, Ngāti Whātua chief Āpihai Te Kawau gifted it to Captain Hobson in order to entice him to select Auckland as the new capital for the colony.[14] A flagpole was to be erected on the summit and the island claimed for the Crown, but upon hearing what was transpiring, Brown and Campbell returned to their island and protested their right to occupy the island. The idea was abandoned, but Governor Hobson refused the application for a Crown grant made by Brown in August 1840. The official reason for the refusal was that Brown and Campbell's purchase was made after Sir George Gipps' 1840 proclamation forbidding direct land purchases from the Maori. It was not until Robert FitzRoy assumed the role of governor in 1843 that Brown and Campbell's fortunes changed. The grant was officially made on 22 October 1844.[15][16]

Campbell left the island in December 1840 to set up a trading business in the newly established settlement of Auckland,[17][18] while Brown remained on the island until February the following year to manage the pig farm, and likely to watch over their vested interest in the island. In 1856 both men left the colony for Great Britain, appointing a resident manager in charge of their affairs. Campbell eventually bought out Brown's share in their business, including Motukorea, in May 1873 for £40,000 when Brown refused to return from Britain to resume control of their affairs. This transaction was carried out via William Baker who appears to have acted as an intermediary, receiving Brown's share for two days while the transaction was being carried out. In 1877 Campbell proposed to transplant olive trees to Motukorea and 5000 seedlings were grown in a nursery on One Tree Hill for this purpose, but were never transplanted.[19] Campbell eventually sold the island to the Featherstone family in 1879, who built a larger house on the north-eastern side of the island which burnt down in 1915.[20] The derelict house was still on the island until the 1960s.

Devonport Steam Ferry Company

editIn 1906 the island was sold to the Alison family who operated the Devonport Steam Ferry Company, and during their ownership the hulks of 4 coal powered low draught paddle steamers were abandoned on the low western end of the island.[21][22] Browns Island is also significant in aviation history, with the Barnard brothers of Auckland carrying out what may have been New Zealand's first glider flights from the upper slopes of the cone in June 1909.[23] In the 1920s the Devonport Steam Ferry Company regularly brought picnickers to the island landing them on a substantial wooden wharf about 120 ft long on the north side of the island.[24] A 1922 survey plan shows a cottage in on the north western flat presumably built to replace the one that was lost in 1915.

Public ownership

editThe Auckland Metropolitan Drainage Board purchased the island in 1946 proposing to build a sewage treatment plant. Controversy surrounding the proposal forced the plan to be abandoned and the island was eventually purchased by Sir Ernest Davis, who presented it as a gift to the people of Auckland in July 1955.[25] Ernest Davis had been the chairperson of the Devonport Steam Ferry Company for 20 years which may further explain some of his affinity with Browns Island.[26] The Auckland City Council administered the island until 1968 when it became part of the Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park.[27] Management control was vested in the Department of Lands and Survey and in 1987 this was transferred to the Department of Conservation. After the demise of the Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park Board in July 1990, the Auckland City Council was again the designated administering body, and passed back the responsibility for management to the Department of Conservation.

In November 2016 a woman became stranded on the island. She was rescued after a fire she lit to attract attention started burning out of control.[28]

Features

editBrowns Island is part of the Hauraki Gulf Maritime Park. There are three pa sites on the island, with the largest occupying the slopes of the main scoria cone. The island's highest point is 68 metres (223 ft) above sea level.

The mineral motukoreaite was discovered in 1977 on the island and named for it.[29]

Other features include a collapsed Lava cave depression which can be seen on the northwestern flats of the island.

Access

editThe island is not served by ferries, so private boats and seaplanes are the only means of access.

There is no wharf or easy access to the island for larger vessels. For small craft the best landing is on the more sheltered northern side of the island where there is a 100 m (328 ft) long beach, backed by a steep cliff. Navigation is difficult as there is a 70 m (230 ft) long rock reef parallel to the beach. The reef is marked by a beacon. Inside the reef there are small isolated rocks but there is sufficient water between them for a small (up to 6 m or 19.7 ft) craft to move. A crew member should be placed in the bow to give instructions to the skipper.

Access to the rest of the island is via a steep, unformed path up the small headland at the north end of the beach. The path is only suited to fit, agile walkers. The flatter areas to the west have very large part submerged mussel beds which extend out 100 m (328 ft) from the shore preventing easy landing.

The closest mainland boat ramps are at Bucklands Beach or Half Moon Bay Marina.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Hayward, Bruce (2019). Volcanoes of Auckland: A Field Guide. Auckland University Press. p. 65.

- ^ Hopkins, Jenni L.; Smid, Elaine R.; Eccles, Jennifer D.; Hayes, Josh L.; Hayward, Bruce W.; McGee, Lucy E.; van Wijk, Kasper; Wilson, Thomas M.; Cronin, Shane J.; Leonard, Graham S.; Lindsay, Jan M.; Németh, Karoly; Smith, Ian E. M. (3 July 2021). "Auckland Volcanic Field magmatism, volcanism, and hazard: a review". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 64 (2–3): 213–234. doi:10.1080/00288306.2020.1736102. hdl:2292/51323.

- ^ a b c Cameron, Ewen; Hayward, Bruce; Murdoch, Graeme (2008). A Field Guide to Auckland: Exploring the Region's Natural and Historical Heritage (Revised ed.). Random House New Zealand. pp. 279–280. ISBN 978-1-86962-1513.

- ^ "Estuary origins". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Phillips, F. L. (1989). Nga Tohu a Tainui. Landmarks of Tainui: Historic Places of the Tainui People. Volume 2. Tohu Publishers.

- ^ Phillips 1989:3

- ^ Monin 1996:42

- ^ Frederickson 1991

- ^ Cruise 1824:200-204

- ^ Elder 1932:312-313

- ^ Wright 1950:156-7

- ^ Campbell 1881:229-253

- ^ Campbell 1881:239ff

- ^ Campbell 1881:300ff

- ^ Monin 1996:42-3

- ^ Deeds CT 364/284

- ^ Campbell 1881:330

- ^ Stone 1982:88

- ^ Stone 1987:117

- ^ Rickard 1985:11

- ^ Maffey 1972

- ^ Auckland.R Wolfe.p234. Random House.2002. Auckland.

- ^ Brassey 1996:3

- ^ Auckland. p234.

- ^ Bush 1980

- ^ Bush, Graham W. A. "Davis, Ernest Hyam 1872-1962". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- ^ NZ Gazette 20/6/1968 No.38 p.1035

- ^ "Woman stranded on island lit fires, police say". Radio New Zealand. Retrieved 6 September 2020.

- ^ "Motukoreaite". Mindat. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

References

edit- Bercusson, L. 1999 The Hauraki Gulf: From Bream Head to Cape Colville", Shoal Bay Press

- Brassey, R. 1996. Motukorea (Browns Island) unpublished MS

- Bush, G. 1980. The Brown's Island Drainage Controversy. Dunmore Press, Palmerston North

- Campbell, J.L. 1881. Poenamo: Sketches of the Early Days of New Zealand, Romance and Reality of Antipodean Life in the Infancy of a New Colony. Williams and Norgate, London. pp. 229–253, 300-308

- Cruise, R.A. 1823. Journal of a Ten Month's Residence in New Zealand. Longmans, London

- Elder, J. R. (ed) The Letters and Journals of Samuel Marsden 1765-1830. Otago University Council, Dunedin

- Frederickson, C. 1991. Description of a lithic assemblage from Motukorea (Brown's Island). Archaeology in New Zealand 34(2):91-104

- Homer, L., Moore, P. and L. Kermode. 2000. Lava and Strata: A guide to the volcanoes and rock formations of Auckland, Landscape Publications and the Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences (pages 28–29)

- Maffey, N.A.. 1972. Auckland Maritime Society Excursion to Brown's Island – 2 December 1972. MS in Auckland Public Library

- Monin, P, 1996. ‘The Islands Lying Between Slipper Island in the South-East, Great Barrier Island in the North and Tiritiri–Matangi in the North-West’, report commissioned by the Waitangi Tribunal

- Phillips, F.L. 1989. Nga Tohu a Tainui. Landmarks of Tainui: Historic Places of the Tainui People. Volume 2. Tohu Publishers, Otorohanga

- Rickard, V. 1985. Motukorea Archaeological Survey. Unpublished report to the Department of Lands and Survey, Auckland. Archaeological and Historical Reports No.11

- Stone, R.C.J. 1982. Young Logan Campbell. Auckland University Press, Auckland

- Wright, O. 1950. New Zealand 1826-27. Wellington

- Volcanoes of Auckland: A Field Guide. Hayward, B.W.; Auckland University Press, 2019, 335 pp. ISBN 0-582-71784-1.

External links

edit- Browns Island (Motukorea), Department of Conservation (includes link to map)

- Aerial photo, GNS Science.

- Details of motukoreaite

- Photographs of Brown's Island held in Auckland Libraries' heritage collections.