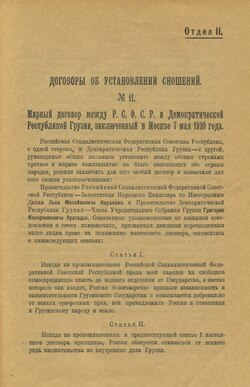

The Treaty of Moscow (Russian: Московский договор, Moskovskiy dogovor; Georgian: მოსკოვის ხელშეკრულება, moskovis khelshekruleba), signed between Soviet Russia (RSFSR) and the Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG) in Moscow on 7 May 1920, granted de jure recognition of Georgian independence in exchange for promising not to grant asylum on Georgian soil to troops of powers hostile to Bolshevik Russia.

| Peace Treaty between the R.S.F.S.R. and the Democratic Republic of Georgia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Peace treaty |

| Signed | 7 May 1920 |

| Location | Moscow |

| Effective | 7 May 1920 |

| Signatories |

|

| Parties |

|

Background

editThe Democratic Republic of Georgia, led by the Social Democratic Party, or Menshevik Party, declared its independence from Russia on 26 May 1918. It was not formally recognised by the Soviets at that time, but the Georgian government eventually managed to obtain de facto recognition from the White leaders and the Allies.

Following an abortive Bolshevik coup in Tbilisi and a failed attempt by the Red Army units to penetrate Georgia in early May 1920, Vladimir Lenin's government agreed to sign a treaty with Georgia and to recognise its independence de jure if the Mensheviks formally undertook not to grant shelter on Georgian territory to any force hostile to Soviet Russia. Many Georgian politicians, including Foreign Minister, Evgeni Gegechkori regarded that clause as an infringement of Georgia's sovereignty and supported the rejection of the Russian terms. However, Georgian Prime Minister Noe Zhordania was anxious above all to secure for Georgia international recognition and so agreed to then.

The treaty was finally signed in Moscow by Grigol Uratadze for Georgia and Lev Karakhan for Russia on 7 May 1920.

Provisions

editArticle 1 of the treaty of 7 May granted unconditional de jure recognition to Georgia by Russia:

Article I:

Proceeding from the right, proclaimed by the RSFSR, of all peoples to free self-determination up to and including separation from the State of which they constitute a part, Russia unreservedly recognizes the independence and sovereignty of the Georgian State and voluntarily renounces all the sovereign rights which had appertained to Russia with regard to the People and Territory of Georgia.[1]

Article 2 Russia promised to abstain from any interference in her internal affairs:

Article II: Proceeding from the principles proclaimed in Article I above of the present Treaty, Russia undertakes to refrain from any kind of interference in the affairs of Georgia.[2]

Article 3 established the frontier between the two countries, providing for the demilitarization, until 1 January 1922, of all mountain passes on the Russo-Georgian border:

Article III: The state frontier between Russia and Georgia, runs from the Black Sea, along the River Psou ... and continues along the northern frontier of the former Chernomorsk, Kutais, and Tiflis provinces to the Zakatalsk circuit and along the eastern boundary thereof up to the frontier of Armenia. The summits of all mountains along this boundary line shall be considered neutral until 1 January 1922. ... The exact determination of the state boundary between the two contracting parties shall be carried out by a special mixed boundary commission composed of an equal number of representatives of each party. The results of the work of this commission shall be confirmed by a special treaty.[1]

Article 4 defined Georgian territories and declared that Russia would recognize as belonging to Georgia any territory the latter might acquire by treaty from her neighbours.

Article 5 was a promise by Georgia to disarm and intern all military and naval units which pretended to be the government of Russia or of the states allied with her, as well as persons, organizations, and groups whose purpose it was to depose the Government of Russia or of her allies.

Article 10 was a promise by Georgia to undertake to exempt from punishment and further administrative or judicial prosecution all persons who had in the past been working in favour of the R.S.F.S.R. or the Communist Party.

Article 11 pledged both countries to respect one another’s flags and emblems.

Article 12 accorded most favoured nation treatment to the commerce of each country in the territory of the other.

Article 13 scheduled a commercial treaty for conclusion in the near future.[3]

Article 14 scheduled the establishment of diplomatic relations pending a special convention concerning the mutual status of their consuls.

Article 15 entrusted the settlement of questions of public and private rights arising between citizens to special Russo-Georgian mixed commissions.[1]

Article 16 stated that the treaty would come into force from the moment it was signed and would not require ratification.[3]

Secret Supplement

editArticle 1 of the secret supplement stated:

“Georgia pledges itself to recognize the right of free existence and activity of the Communist party … and in particular its right to free meetings and publications (including organs of the press)."[4]

In no case could repressive measures be taken against private persons because they engaged in propaganda and agitation in favour of the Communist programme, nor against groups and organizations based upon it. This article actually curtailed Georgian sovereignty. For all practical purposes it annulled Article 2 of the Russo-Georgian treaty, in which Russia had promised not to interfere in the internal affairs of Georgia. Now Article 1 of the Secret Supplement by implication was giving Russia the right to interfere in favour of the Georgian Bolsheviks, whose freedom was guaranteed by treaty.[3]

Aftermath

edit1920s

editIn spite of brief Menshevik euphoria of the declared diplomatic success, public opinion in Georgia denounced the treaty as "veiled subjection of Georgia to Russia", as was reported by the British Chief Commissioner Sir Oliver Wardrop.[4] The government was subjected to harsh criticism over the concessions made to Moscow from the parliamentary opposition, particularly from the National Democratic Party. Nevertheless, the Treaty of Moscow had a short-term benefit to Tbilisi by encouraging the reluctant Allied Supreme Council and other governments to recognise Georgia de jure on 11 January 1921.[5]

The treaty did not resolve the conflict between Russia and Georgia. Although Soviet Russia had recognised Georgia's independence, the eventual overthrow of the Menshevik government was both intended and planned,[6] and the treaty was merely a delaying tactic on the part of the Bolsheviks,[7] who were then preoccupied with an uneasy war against Poland.[8]

According to the agreement, the Georgian government released most of the Bolsheviks from prison. They quickly established a nominally-autonomous Communist Party of Georgia, which, under the coordination of Caucasus Bureau of the Russian Communist Party, immediately activated their overt campaign against the Menshevik government and so were rearrested by energetic Interior Minister Noe Ramishvili. That caused protests from the newly-appointed Russian Ambassador Plenipotentiary Sergey Kirov, who exchanged fiery notes with Evgeni Gegechkori. The conflict, never finally resolved, was subsequently used in Soviet propaganda against the Menshevik government, which was accused by Moscow of harassing the communists, obstructing the passage of convoys passing through to Armenia and supporting an anti-Soviet rebellion in the North Caucasus. On the other hand, Georgia accused Russia of fomenting antigovernment riots in various regions of the country, especially among ethnic minorities such as Abkhazians and Ossetians, and of provoking border incidents along the frontier with Soviet Azerbaijan.

After nine months of fragile peace, in February 1921, the Soviet Red Army launched a final offensive against Georgia, under the pretext of supporting the rebellion of peasants and workers in the country, put an end to the Democratic Republic of Georgia, and established Soviet Georgia, which would last for the next seven decades.

1990s and 2000s

editAs Georgia was moving towards independence from the Soviet Union, the Georgian government, led by Zviad Gamsakhurdia, addressed the Russian President Boris Yeltsin and stating that "the only legitimate framework for relations" between Russia and Georgia could be the 1920 treaty. Moscow refused, and Georgia declared Soviet troops in Georgia an occupation force.[9]

Parallels have been drawn in modern Georgia between the Georgian–Russian diplomacy in 1920 and the 2000s. In response to indications by several senior Russian diplomats that Moscow wanted to see Georgia "a sovereign, neutral and friendly country", rather than a member of military alliances such as NATO, Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili said on 25 October 2007 that neutrality was not an option for Georgia because "Georgia signed an agreement on its neutrality in 1920 with Bolshevik Russia and after six months Georgia was occupied".[10]

References

edit- ^ a b c "Georgian Independence". Seventeen Moments in Soviet History. 2015-08-26. Retrieved 2021-11-13.

- ^ Beichman, A. (1991). The Long Pretense: Soviet Treaty Diplomacy from Lenin to Gorbachev, p. 165. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-88738-360-2.

- ^ a b c Kazemzadeh, Firuz (2008). The struggle for Transcaucasia (1917–1921) ([New] ed.). London: Anglo Caspian Press. ISBN 978-0-9560004-0-8. OCLC 303046844.

- ^ a b Lang, DM (1962). A Modern History of Georgia, p. 226. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- ^ Skinner, Peter (2014). Georgia: The Land Below the Caucasus. Narikala Publications. p. 469. ISBN 978-0-9914232-0-0.

- ^ Erickson, J., editor (2001). The Soviet High Command: A Military-Political History, 1918–1941, p. 123. Routledge (UK). ISBN 0-7146-5178-8.

- ^ Sicker, M. (2001). The Middle East in the Twentieth Century, p. 124. Martin Sicker. ISBN 0-275-96893-6.

- ^ Debo, R. (1992). Survival and Consolidation: The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918–1921, p. 182. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 0-7735-0828-7.

- ^ Toria, Malkhaz (2014). "The Soviet occupation of Georgia in 1921 and the Russian-Georgian war of August 2008: historical analogy as a memory project". In Jones, Stephen F. (ed.). The Making of Modern Georgia, 1918–2012: The First Georgian Republic and Its successors. Routledge. p. 318. ISBN 978-1317815938.

- ^ Saakashvili Rules Out Georgian Neutrality. Civil Georgia. 2007-10-25. Retrieved on 2008-06-15.

External links

edit- (in English) Full text of the Treaty. soviethistory.org