This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The planes of the Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying game constitute the multiverse in which the game takes place. Each plane is a universe with its own rules with regard to gravity, geography, magic and morality.[1] There have been various official cosmologies over the course of the different editions of the game; these cosmologies describe the structure of the standard Dungeons & Dragons multiverse.

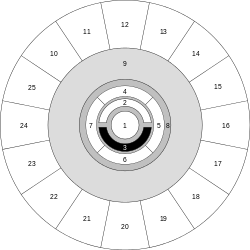

- Inner Planes: Material Plane (1), Positive (2) and Negative (3) Planes, Elemental Planes (4–7);

- Ethereal (8) and Astral (9) Planes;

- Outer Planes (10–25)

The concept of the Inner, Ethereal, Prime Material, Astral, and Outer Planes was introduced in the earliest versions of Dungeons & Dragons; at the time there were only four Inner Planes and no set number of Outer Planes. This later evolved into what became known as the Great Wheel cosmology.[2]: 86 The 4th Edition of the game shifted to the World Axis cosmology. The 5th Edition brought back a new version of the Great Wheel cosmology which includes aspects of World Axis model.[3]

In addition, some Dungeons & Dragons settings have cosmologies that are very different from the "standard" ones discussed here.[2]: 95 For example, the Eberron setting has only thirteen planes, all of which are unique to Eberron.[4]

Publication history

editThe cosmology of the planes was presented for the first time, as part of the Great Wheel of Planes, in Volume 1, Number 8 of The Dragon, released July 1977.[5] In the article "Planes: The Concepts of Spatial, Temporal and Physical Relationships in D&D", Gary Gygax mentions that there are 16 Outer Planes.[6] The "Basic edition" of D&D had a separate, though similar, cosmology from that of its contemporary AD&D game, which is a more open planar system that is less regulated than that of its counterpart.

The planes were further "refined in the Players Handbook (1978) and Deities & Demigods (1980)".[5] The appendix of the Player's Handbook included an abstract diagram of the planes, and mentioned the same 16 Outer Planes.[7] Shannon Appelcline, the author of Designers & Dragons, highlighted that throughout the early 1980s Dragon magazine would continue to detail "some of the planes in more depth", however, "there was no overarching plan for the planes of D&D other than a few increasingly old drawings".[5] The multiverse of the Basic D&D game was expanded with the D&D Immortals Rules (1986) set. The Astral Plane runs through and links the rest of the Multiverse. Plane can range in size from the tiniest Attoplane (1/3 inch long), to the Standard Plane (.085 light-years long), up to the Terraplane (851 billion light years long), with stars and planets scaled to match the size of the plane.[8]

Both Appelcline[5][9] and Curtis D. Carbonell, in his book the Dread Trident: Tabletop Role-Playing Games and the Modern Fantastic, highlighted that information on the planes and the shared cosmology was codified in the Manual of the Planes (1987) and Tales of the Outer Planes (1988).[2] Carbonell wrote that project leader and designer Jeff Grubb detailed "the schematization of the planes' requisite five area: the Prime Material, the Ethereal, the Astral, the Inner, and the Outer planes. This basic structure is still used in 5e, with some changes that provide minor rearrangements and clarifications [...]. Grubb's approach demonstrated a need to codify, while still remaining flexible, that has remained as a primary aim of the latest edition".[2]: 93

Carbonell also highlighted that the 1989 Spelljammer campaign setting added cosmology that "allowed travel between the different settings" such as Dragonlance, Greyhawk, and the Forgotten Realms.[2]: 97 However, campaign settings such as Dark Sun and Ravenloft were inaccessible in this cosmology.[2]: 97 Then in 1993, TSR wanted to do a series of books about the Outer Planes which Zeb Cook said led to the creation of the Planescape campaign setting released in 1994.[10] This campaign setting provided a framework to create adventures across the planes with the city of Sigil acting as a hometown and starting point for players.[11] Carbonell called this setting "the most complex example of the multiverse created during the varieties of 2e's AD&D settings" and wrote: "A more nuanced and sophisticated attempt at harmonization, Planescape provided an alternate way to travel between the planes than Spelljammer's science-fantasy-oriented approach".[2]: 98 The 3rd edition Manual of the Planes (2001) detailed both the inner and outer planes. Kevin Kulp, for DMs Guild, wrote that "the authors used an approach that said 'here's how it's been done in the past, and here are other ways you can do it,' which allowed the book to avoid setting planar mechanics in stone. Instead it gave DMs a modular approach by presenting Options, a flexible strategy that pleased both 1e and Planescape fans. Vast amounts of new ideas and new locations were presented, dovetailing nicely with canon from earlier editions".[12]

The 4th edition shifted the locations of the various planes to fit the new World Axis cosmology and added the Parallel Planes of the Feywild and the Shadowfell to the game; many of the changes were detailed in that edition's Manual of the Planes (2008).[3][13][14] However, the 5th edition Player's Handbook (2014) and Dungeon Master's Guide (2014) shifted most of the cosmology of the planes back to the Great Wheel model with some aspects of the World Axis model retained in the descriptions of the inner planes.[3][15][16]

Great Wheel cosmology

editThe cosmology outlined in the Great Wheel model contains sixteen Outer Planes which are arranged in a ring of sixteen planes with the Good-aligned planes (or Upper Planes) at the top, and the Evil-aligned planes (or Lower Planes) at the bottom. Depictions usually display the Lawful planes (or Planes of Law) to the left, and the Chaotic planes (or Planes of Chaos) to the right. Between all of these sit the Neutral planes, or the Planes of Conflict.[17][15][18] The center contains the Inner and Material Planes.[3]

One further plane sits in the center of the ring, the Outlands, being neutral in alignment. At the center of the Outlands is a Spire of infinite height; the city of Sigil floats above the Spire's pinnacle.[15][19]

Many Outer Planes were renamed in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition in the Planescape campaign setting, released in 1994. In the 3rd Edition Manual of the Planes (2001), the old and new names were combined, the Demiplane of Shadow was promoted to the Plane of Shadow, the Prime Material Plane was shortened to the Material Plane, and it was stated that each Material Plane is connected to its own unique Ethereal Plane.

The cosmology is usually presented as a series of concentric circles, with alternating spatial and transitive planes; from the center outwards, they are ordered as follows: Inner, Ethereal, Material, Astral, Outer Planes, and the Far Realm. The Shadow Plane and the Dimension of Time, if they are included, are separate from the others, and usually represented as being connected to the Material Plane. Demiplanes, although most commonly connected to the Ethereal Plane, can be found attached to any plane. All planes, save the demiplanes, are infinite in extent.

Planes may border (be coterminous) or may be coexistent. In particular, the Ethereal and Shadow planes are coexistent with the Material Plane. In effect, the "boundary" between the two extends through all of space. Thus a ghost in Dungeons & Dragons, which is an ethereal creature, has a location on the Material Plane when it is near the border of the Material and Ethereal planes. It can "manifest" itself into the Material, and force attacks launched from the Material can hit it.[20][21][22]

Inner Planes

editThe Inner Planes are made up of elemental matter and forces. They consist of the Elemental Planes[1] of air, earth, fire and water, and the Energy Planes. Some descriptions also contain the Para-elemental (magma, ice, etc.) and Quasi-elemental planes (lightning, dust, etc.) linking them.[1] The energy planes are the Positive Material Plane and Negative Material Plane.

In his review of the Planescape Campaign Setting boxed set, Gene Alloway felt that the set would provide players with a good sense of "the sheer force of nature that drives all the Inner Planes. The Inner Planes don't have anything against you—they're hard on everyone."[23] Backstab magazine reviewers Lord Winfield and Kaneda found the Inner Planes among the places in the Planescape setting least visited by player characters, which do not lend themselves to a prolonged stay.[1][24]

While the 5th Edition returned to the Great Wheel model, the Inner Planes detailed in that edition "retain aspects" of the 4th Edition World Axis model: "The four elemental planes are back, but they remain tightly integrated with the material plane as its creative foundation. The paraelemental planes have also returned for the first time since Planescape, but they have more evocative names. The Plane of Ash is known as the Great Conflagration, the Plane of Ice is the Frostfell, the Plane of Magma is the Fountains of Creation, and the Plane of Ooze is the Swamp of Oblivion. Additionally, the Elemental Chaos is the churning realm within which the Inner Planes are held".[3] Screen Rant highlighted that the parts of the Inner Planes closest to the Material Plane will seem the most familiar to adventurers with features such as humanoid inhabitants and cities. However, the further adventurers venture "out into the Inner Planes, things become less familiar. Each plane starts to resemble its purest form, making it harder to travel without powerful magical spells that protect the party from the environment. If a traveler goes far enough, they will reach the Elemental Chaos, where the boundaries of the Inner Planes start to break down – and where some truly alien monsters exist".[25]

Material Planes

editThe Material Planes are worlds that balance between the philosophical forces of the Outer Planes and the physical forces of the Inner Planes—these are the standard worlds of fantasy RPG campaigns. The Prime Material Plane is where the more 'normal' worlds exist, many of which resemble Earth. The 2nd edition Dungeon Master's Guide states there are several Prime Material Planes, but several other 2nd edition products say there is only one Prime Material Plane rather than several.

Introduced in the Spelljammer setting, the Phlogiston is a part of the Material plane. It is a highly flammable gaseous medium in which crystal spheres holding various Prime Material solar systems float, traversable by Spelljammer ships.[26]

The Feywild and the Shadowfell, the Parallel Planes introduced in the 4th Edition World Axis model, were incorporated into the 5th Edition version of the Great Wheel model.[27][28] In 2015, D&D Creative Director Chris Perkins stated that 4th Edition sourcebooks on these planes were the best source of information for the 5th Edition.[28] The adventure module The Wild Beyond the Witchlight (2021) is the first in-depth 5th Edition exploration of the Feywild and builds on the description included in the 5th Edition Dungeon Master's Guide (2014).[29][30][31]

Outer Planes

editAlignment-based planes. The home of gods, dead souls, and raw philosophy and belief.

| Outer Planes | ||||

| Mount Celestia |

Bytopia | Elysium | Beastlands | Arborea |

| Arcadia | ↑Good↑ | Ysgard | ||

| Mechanus | ←Lawful | Outlands | Chaotic→ | Limbo |

| Acheron | ↓Evil↓ | Pandemonium | ||

| Nine Hells of Baator |

Gehenna | Hades | Carceri | Abyss |

Transitive planes

editThe transitive planes connect the other planes and generally contain little, if any, solid matter or native life.

Astral Plane

editThe Astral Plane is the plane of thought, memory, and psychic energy; it is where gods go when they die or are forgotten (or, most likely, both). It is a barren place with only rare bits of solid matter. The Astral Plane is unique in that it is infinitesimal instead of infinite; there is no space or time here, though both catch up with beings when they leave. The souls of the newly dead from the Prime Material Plane pass through here on their way to the afterlife or Outer Planes.

The most common feature of the Astral Plane is the silver cords of travelers using an astral projection spell. These cords are the lifelines that keep travelers of the plane from becoming lost, stretching all the way back to the traveler's point of origin.

A god-isle is the immense petrified remains of a dead god that float on the Astral Plane, where githyanki and others often mine them for minerals and build communities on their stony surfaces. Tu'narath, the capital city of the githyanki, is built on the petrified corpse of a dead god known only as "The One in the Void". God-isles often have unusual effects on those nearby, including causing strange dreams of things that happened to the god when it was alive. God-isles are also the only locations on the Astral Plane that are known to possess gravity or normal time flows.

Part of Baldur's Gate II: Shadows of Amn takes place on the Astral Plane.[32]

Trenton Webb for Arcane magazine comments that A Guide to the Astral Plane "breathes life into what had hitherto been little more than a planar motorway. Essentially infinite and filled with few 'solid locations' or indigenous species, the Astral Plane should by rights be a dull place. Yet with some deft imaginative touches and sleight of logic, the guide transforms this dead zone into a wonderfully different 'world'." He adds that "By expanding the accepted 'physics' of the Astral plane and applying classic Planescape thinking, the Silver Void is made solid and comprehensible."[33]

Ethereal Plane

editThe Ethereal is often likened to an ocean, but rather than water it is a sea of boundless possibility. It consists of two parts: the Border Ethereal which connects to the Inner and Prime Material planes, and the Deep Ethereal plane which acts as the incubator to many potential demiplanes and other proto-magical realms. From a Border Ethereal plane a traveler can see a misty greyscale version of the plane from which they are traveling; however, each plane is only connected to its own Border Ethereal, which means inter-planar travel necessitates entering the Deep Ethereal and then exiting into the destination plane's own Border Ethereal plane. Many demiplanes, such as that which houses the Ravenloft setting, can be found in the Deep Ethereal plane; most demiplanes are born here, and many fade back into nothingness here. Unlike the Astral Plane, in which solid objects can exist (though are extremely rare) anything and everything that goes to the Ethereal Plane becomes Ethereal. There is also something here called the Ether Cyclone that connects the Ethereal plane to the Astral Plane.

In the 3rd Edition, each Material Plane is attached to its own unique Ethereal Plane; use of the Deep Ethereal connecting these Ethereal Planes together is an optional rule.

Plane of Shadow

editA fictional plane of existence in Dungeons & Dragons, under the standard planar cosmology.[34] A dimly lit dimension that is both conterminous to and coexistent with the Material Plane. It overlaps the Material Plane much as the Ethereal Plane does, so a planar traveler can use the Plane of Shadow to cover great distances quickly. The Plane of Shadow is also conterminous to other planes. With the right spell, a character can use the Plane of Shadow to visit other realities. It is magically morphic, and parts continually flow onto other planes. As a result, creating a precise map of the plane is next to impossible, despite the presence of landmarks. The Plane of Shadow is replaced by the Shadowfell in the 5th Edition.

In first edition AD&D, the Plane of Shadow was the largest Demi-Plane of the Ethereal Plane.[35]

Mirror planes

editMirror planes were introduced in the Third Edition Manual of the Planes as an optional group of transitive planes. They are small planes that each connect to a group of mirrors that can be located in any other planes throughout the multiverse. A mirror plane takes the form of a long, winding corridor with the mirrors it attaches to hanging like windows along the walls. Mirror planes allow quick travel between the various mirrors that are linked to each, but each plane contains a mirror version of any traveler that enters it. This mirror version has an opposite alignment and will seek to slay their real self to take their place. All mirrors connect to a mirror plane, though each mirror plane usually has only five to twenty mirrors connecting to it.

Temporal Plane

editThe Plane of Time was known as the Temporal Prime in the 1995 book Chronomancer. It is a plane where physical travel can result in time travel.

In 3rd edition products, some of the detail of Temporal Prime became incorporated into the "Temporal Energy Plane" mentioned in the 3rd edition Manual of the Planes. Dragon Magazine No. 353 associates it also with the "Demiplane of Time" that has appeared in various forms since 1st edition.

Demiplanes

editDemiplanes are minor planes, most of which are artificial. They are commonly created by demigods and extremely powerful wizards and psions. Naturally-occurring demiplanes are rare; most such demiplanes are actually fragments of other planes that have somehow split off from their parent plane. Demiplanes are often constructed to resemble the Material Plane, though a few—mostly those created by non-humans—are quite alien. Genesis, a 9th level arcane spell or psionic power, and the 9th-level arcane spell Demiplane Seed are among the few printed methods for a player character to create a demiplane.

Among the most notable of demiplanes is the Demiplane of Dread, the setting of Ravenloft.

Neth

editNeth, the Demiplane That Lives, was first presented in A Guide to the Ethereal Plane, a sourcebook for the Planescape setting of AD&D Second Edition. It is a living, sentient plane of finite size that has an immense curiosity. The only access Neth has to the rest of the multiverse is through a single metallic, peach-colored pool on the Astral Plane. Those who look into the pool from the Astral Plane might notice a huge eye flash into focus on its surface, which quickly fades. The only thing native to Neth is the plane itself. Neth creates humanoid subunits of itself called Neth's Children, sometimes for specific short-term purposes before reabsorbing them. At Neth's center is a thick knot of membrane at least a mile across where all the folds come together. This serves as Neth's brain. Other parts of the membrane also serve specific functions, which include areas where the membrane can be easily deformed for communication, encapsulation, and budding Neth's Children.

The Visage Wall is an area of Neth's membrane where Neth communicates with visitors. It contains thousands of head-shaped bumps that resemble the likenesses of those previously absorbed by Neth. Neth speaks to its visitors from about five or six of the heads simultaneously, questioning them to learn more of the outside universe. Sometimes, Neth will choose to encapsulate its visitors. Two folds of membrane will come together and ensnare and seal off the victims. Neth will then flood the compartment with either preservative or absorptive fluid. The preservative fluid will put the victim in temporal stasis, and the victim can be revived if the fluid is drained away. If the compartment is flooded with absorptive fluid, the victim will dissolve and be absorbed into Neth itself, including the victim's memories.

Gravity on Neth is the same strength as that on the material world; however, Neth chooses the direction of gravity's pull and may change it at will. Time is normal on Neth. Neth can move its interior membrane at will, creating or destroying fluid-filled spaces.

Other planes

editFar Realm

editThe Far Realm is an alien dimension of cosmic horror. It is the home plane for many aberrations and strange monsters.

The Far Realm's mix of horror, madness, and strange geometries was largely inspired by the work of American writer H. P. Lovecraft.[36][37] It is particularly inspired by Lovecraft stories like "Through the Gates of the Silver Key".[citation needed] It was created by Bruce Cordell, and introduced in the Second Edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons adventure module The Gates of Firestorm Peak (1996).[38][37] James Jacobs later called Cordell's work an "adventure with a distinctly Lovecraftian feel", noting that "Deep inside Firestorm Peak lies a portal to an insidious region beyond sanity and light known only as the Far Realm, and the unknowable but hostile entities of this hideous region prepare to pass through into the world."[36] The adventure featured a magical portal that produced creatures and energies from the Far Realm.[39]

In Third Edition, the Far Realm was incorporated into the Realm of Xoriat in the Eberron campaign setting.[37] In Fourth Edition, the Far Realms were included in the new cosmology design of Dungeons & Dragons.[38] In this edition, members of the Warlock class can forge a pact (called the Starpact) with the entities from or near the Far Realm to gain power.[40]: 32 The Far Realm's association with the new setting has been detailed in various supplements. The Far Realm contains an infinite number of layers, these layers range from inches thick to miles, and it is often possible to perceive multiple layers simultaneously. These layers can grow, spawn further layers, breathe and possibly die. The Far Realm is home to many powerful and unspeakable beings ripped from the nightmares of the darkest minds of the waking world, beings so unfathomable that their very existence is a perversion of reality itself. These beings are governed by lords of unimaginable power and knowledge completely alien. The Far Realm is a plane far outside the others and often not included in the standard cosmology. It is sometimes referred to simply as "Outside", because in many cosmologies it is literally outside reality as mortals understand it.

Plane of Dreams

editThe Plane of Dreams is a plane far outside the others and often not included in the standard cosmology. As its name suggests, all true dreams take place on the Plane of Dreams.[citation needed]

The World Axis cosmology

edit4th edition uses a simplified default cosmology with only six major planes, each of which has a corresponding creature origin. The Astral Sea, Elemental Chaos, Feywild and Shadowfell are covered extensively in the Manual of the Planes, while the Far Realm and Sigil are covered briefly.[41][42] Supplemental sourcebooks relating to the Elemental Chaos (The Plane Below) and the Astral Sea (The Plane Above) were released in 2009 and 2010, respectively. The Ethereal Plane has been removed entirely.

Fundamental Planes

editThe fundamental planes are two vast expanses from which the other planes were formed. It was the conflict between the inhabitants of each fundamental plane that constituted the Dawn War. The two Fundamental Planes are theoretically infinite; it is implied that if one departs the world of one campaign setting and sets out through either the Astral Sea or the Elemental Chaos, they will eventually reach the worlds of other campaign settings.

The Astral Sea

editThe Astral Sea corresponds to the Astral Plane of earlier editions. The Astral Dominions, counterparts to the Outer Planes of earlier editions, are planes which float within the Astral Sea. The majority of the gods dwell in Astral Dominions. The Astral Sea itself is spacially infinite, but the Astral Dominions are all finite. Creatures native to or connected with the Astral Sea (such as angels and devils) generally have the immortal origin. The plane is described in The Plane Above: Secrets of the Astral Sea, released in 2010. In the Forgotten Realms setting, the Astral Sea was formed from the collapse of the Outer Planes into the Astral Plane after Mystra's murder, while in Eberron, the Astral Sea is equated with Siberys, the Dragon Above.

- Astral Dominions in the Points of Light setting

- Arvandor, the Verdant Isles: A realm of nature, beauty and magic similar to the Feywild. Home to Corellon and (sometimes) Sehanine.

- Baator, the Nine Hells: A place of sin and tyranny, a world of continent-sized caverns. Home to Asmodeus.

- Celestia, the Radiant Throne: A great mountain that drifts in a world of silver mists. Home to Bahamut, Moradin and, sometimes, Kord.

- Chernoggar, the Iron Fortress: The rust-pitted iron castle, where mighty warriors fight and die endlessly. Home to Bane and Gruumsh.

- Hestavar, the Bright City: a luminous metropolis which floats above sandy beaches and crystal-clear lagoons, the center of astral civilization. Home to Erathis, Ioun and Pelor.

- Kalandurren, the Darkened Pillars: A dominion that plays host to demons. It belonged to the god Amoth before he was killed by the demon lords Orcus and Demogorgon.

- Pandemonium: The former dominion of Tharizdun. The tower of the lich god Vecna is said to be hidden within it.

- Shom, the White Desert: The former dominion of the mysterious God of the Word. Astral giants loyal to the goddess Erathis fight for control of it.

- Tytherion, the Endless Night: A dark, arid wilderness where serpents and dragons lurk. Home to Zehir and Tiamat.

The Elemental Chaos

editThe Elemental Chaos corresponds to the Inner Planes of earlier editions (excluding the Positive and Negative Energy Planes), also containing some aspects of Limbo. The Elemental Chaos contains Elemental Realms, which are themselves planes; the Abyss is one such realm. The only god who dwells in the Elemental Chaos is Lolth, who resides on the 66th layer of the Abyss. The Elemental Chaos is spacially infinite, the Elemental Realms are not. Creatures native to or connected with the Elemental Chaos (including demons) generally have the elemental origin. The plane is described in The Plane Below: Secrets of the Elemental Chaos, released in 2010. In the Forgotten Realms setting, the Elemental Chaos was formed from the collapse of the Inner Planes after Mystra's murder, while in Eberron, the Elemental Chaos is equated with Khyber, the Dragon Below.

- Locations within the Elemental Chaos

- The Abyss: A place of utter evil and corruption, the result of a mad god's attempt to control the whole cosmos. Lolth's home, the Demonweb Pits, can also be found here.

- The City of Brass: The efreeti capital and a major hub of planar trade and travel,[43] the "infamous", "fabled", and "ominous" "geometrical City of Brass" was featured on the cover of the 1st edition Advanced Dungeons & Dragons Dungeon Master's Guide (1979) and "finally laid out in detail" for the Al-Qadim setting in 1993, both depictions by David Sutherland.[44]

- The Keening Delve

- The Ninth Bastion

- Zerthadlun

Parallel Planes

editThe World

editThe equivalent to the Prime Material Plane or Material Plane of earlier editions. This plane lacks a formal name and is most often referred to as the World,[14] although titles such as the Middle World and the First Work were also presented in Manual of the Planes. Creatures native to the world generally have the natural origin. The gods Avandra, Melora and Torog have their homes in the World. The god Vecna wanders the whole cosmos (Sehanine is prone to doing this as well). In the Forgotten Realms setting, the world is named Toril (there is another, inaccessible world called Abeir), while in Eberron, the world is equated with Eberron, the Dragon Between.

The Feywild

editOne of the two parallel planes, the Feywild is a more extreme and magical reflection of the world with some thematic links to the Positive Energy Plane and the Plane of Faerie of earlier editions and settings. Creatures native to or connected with the Feywild (such as elves and gnomes) generally have the fey origin. According to the 4th edition Manual of the Planes, this plane has some sort of unspecified connection to Arvandor, and is suspected that the Dominion of Corellon can be reached by here. Important locales within the Feywild are known as Fey Demesnes.[45] Additional details on the Feywild were included in the 4th edition supplement Heroes of the Feywild (2011) which added storytelling and mechanics themed around the Feywild.[46][47] The Feywild was next explored in-depth in the 5th adventure module The Wild Beyond the Witchlight (2021) and the corresponding Domains of Delight (2021) supplement (an official PDF by Wizards of the Coast released on the Dungeon Masters Guild).[30][48] The 5th edition added the concept of Domains of Delight similar to Ravenloft's Domains of Dread; each domain is ruled by an Archfey who can shape their region via their will.[49] Chris Perkins, Dungeons & Dragons Principal Story Designer, explained that "the Feywild is described in the fifth edition Dungeon Master’s Guide, which builds on material from earlier editions. The Wild Beyond the Witchlight used the DMG’s description as a starting point and expanded from there. The concept of archfey – powerful Fey creatures who carve out domains for themselves – dates back to earlier editions, but this is the first time we’ve given these domains a name".[31]

In the Forgotten Realms setting, the Feywild is also known as the Plane of Faerie and has come into alignment with Toril after countless millennia of drifting away, while in Eberron, the Feywild is equated with Thelanis, formerly known as the Faerie Court.

SyFy Wire highlighted that "traditionally, the Feywild is an alternate plane of existence that mirrors and overlaps the material world. It's a place of perpetual twilight that's full of both enticing beauty and terrible dangers. Time works differently inside the Feywild, and those who leave may find what they thought was a brief venture instead lasted years — assuming they're even able to leave at all. In short, it's a good place for a magical and eerie adventure".[30]

- Locations within the Feywild

- Astrazalian, the City of Starlight

- Brokenstone Vale

- Cendriane

- The Feydark (Underdark of the Feywild)

- Harrowhame

- The Isle of Dread

- Mag Tureah

- Maze of Fathaghn

- Mithrendain, the Autumn City

- The Murkendraw

- Nachtur, the Goblin Kingdom

- Senaliesse

- Shinaelestra, the Fading City

- Vor Thomil

The Shadowfell

editThe Shadowfell is a type of underworld, and the thematic successor to the Negative Energy Plane and Plane of Shadow from earlier editions. The Raven Queen makes her home here rather than the Astral Sea. It also incorporates the Domains of Dread, areas created by the shadows cast by great tragedies in the world. CBR highlighted that "if the Feywild is the Prime Material's dream reflection, the Shadowfell is a mirror of its darkness, drawing from the shadows and gloom in a way that makes it impossible to forget that, where there is light and life, there is also darkness and decay. [...] Home to numerous species, the most prominent entities who dwell in the Shadowfell are mysterious undead beings called shadows. Shadow dragons and shadow mastiffs can also be found there, along with a host of dark, terrifying creatures like wraiths, spectres, darkweavers and shadow demons. There are also a number of humanoid natives, including gnomes, humans, halflings and beings known as Shadar-Kai".[50]

The plane is described in the boxed set The Shadowfell: Gloomwrought and Beyond, released in 2011. In the Forgotten Realms setting, the Shadowfell was formed from what was left of the Plane of Shadow after Mystra's murder, while in Eberron, the Shadowfell is equated with Dolurrh, the realm of the dead.

- Locations within the Shadowfell

- Gloomwrought, the City of Midnight

- Letherna, Realm of the Raven Queen

- The House of Black Lanterns

- Moil, the City That Waits

- Nightwyrm Fortress

- The Plain of Sighing Stones

- The Shadowdark (Underdark of the Shadowfell)

Demiplanes

editDemiplanes are relatively small planes which are not part of larger planes. The most prominent demiplane is Sigil, the City of Doors, which is largely unchanged from earlier editions.

Anomalous planes

editAnomalous planes are planes which do not fit into other categories. The most prominent of these planes are the Realm of Dreams, which can be reached via the Astral Sea, and the Far Realm, which breaks through into the remote parts of the Astral and the world.

The Far Realm

editAn anomalous plane, the Far Realm is a bizarre, maddening plane said to be composed of thin layers filled with strange liquids – at least, that is what the most coherent descriptions say, for though some escape the Far Realm with their lives, most do not do so with their sanity. Visitors to the Far Realm can only exist in one layer at a time, but large Far Realm natives can exist in multiple layers at once. Creatures native to or connected with the Far Realm generally have the aberrant origin. The Far Realm was originally sealed off from reality by a crystalline structure known as the Living Gate, which lay at the top of the Astral Sea. The Living Gate awoke and opened during the Dawn War between the gods and primordials, and was destroyed in the same war, thus enabling freer transit between the planes than should be allowed. Classic creatures such as aboleths, beholders, and mind flayers originate in the Far Realm. Distant stars have been driven mad by proximity to the Far Realm, resulting in the abominations known as starspawn. Natural humanoids tainted by the Far Realm are known as foulspawn. The Far Realm is occasionally referred to as "Outside", because it seems to exist outside of reality as defined by the world, the fundamental planes and the parallel planes.

In Eberron, the Far Realm is equated with Xoriat, the Realm of Madness.

Other fictional interpretations

editWithin the context of the game, there are many theories of the organization of the planes.[2] For instance, in some lands it is believed that there are multiple Prime Material planes, rather than one containing all the worlds or planets. In these lands the Ethereal planes are believed to surround each Prime Material plane.

Additionally, other Dungeons & Dragons cosmologies were developed after Greyhawk for various other campaign settings, however, "they would be subsumed under 5e's umbrella concept of the multiverse".[2]: 95

Dark Sun cosmology

editOne of the hallmarks of the Dark Sun setting was Athas' cosmological isolation, something that broke with the rest of the canonical Dungeons & Dragon's universe.[51] Many of Dark Sun's AD&D contemporaries are accessible via planar travel or spelljamming, but Athas, with very few exceptions, is entirely cut off from the rest of the universe.[52]: 8–9 [53] While it retains its connections to the Inner Planes, access to the Transitive Planes and Outer Planes is nearly impossible. The reason for the cosmological isolation is never fully explained.

Eberron cosmology

editThe Eberron cosmology, used in the original Eberron campaign setting, contained thirteen Outer Planes in 3rd edition,[54] and gained at least two for 4th edition under the new cosmology. They exhibit traits similar to those of the standard D&D cosmology but also some (Irian, Mabar, Fernia, and Risia) appear more like Inner Planes. The cosmology was unique in that the Outer Planes orbited around Eberron through the Astral plane. As they orbited, their overlap with the material plane changed and access to those planes became easier or restricted.

Forgotten Realms cosmology

editThe Forgotten Realms cosmology was originally the same as that of a standard Dungeons & Dragons campaign. The cosmology for the 3rd edition of D&D was altered substantially so that it contained twenty-six Outer Planes, arranged in a tree-like structure around the central 'trunk' of the material plane of Toril. Unlike the Outer Planes of the standard D&D cosmology which were heavily alignment-based, the Outer Planes of the Forgotten Realms cosmology were faith-based.

The planes of the Forgotten Realms were retooled in the 4th Edition to match the new default cosmology, with many of the planes or realms being relocated to the Astral Sea, and a handful now located in the Elemental Chaos. Appelcline highlighted that the 4th Edition World Axis model "had actually originated with the Forgotten Realms, which was planning a view of the heavens as early as 2005 or 2006. It was then co-opted by the SCRAMJET world design team for D&D 4e".[13]

Fictional planar travel

editPortals, conduits and gates are all openings leading from one location to another; some lead to locations in the same plane, others to different planes entirely. Although the three terms are often used interchangeably, there are notable distinctions:

- Portals are bounded by pre-existing openings (usually doors and arches); the portal is destroyed when the opening is. Portals also require portal keys to open; a key is usually a physical object, but it can also be an action or a state of being. Naturally occurring portals will often appear at random (a common occurrence in the city of Sigil, "City of Doors", in the Planescape campaign setting); some portals only exist for a brief period of time, or shift from one location to another.

- Conduits are also naturally occurring, but they are natural phenomena, the planar equivalent of whirlpools and tornadoes. Conduits are only known to occur in the Astral and Ethereal Planes. A type of conduit known as a color pool is a common gateway from the Astral Plane to the Outer Planes. A vortex is a link from a Prime Material world to the Inner Planes, which begin in areas of intense concentration of some element (e.g., the heart of a volcano might be a vortex to the Plane of Fire). There also used to be living vortices which the sorcerer-monarchs of Athas have managed to maintain, like syphoning water through a hose, and use to empower their "priests," the Templars.

- Gates are portals that are not bounded by physical apertures; gates are rare, and usually appear as a result of magical spells and rare planar phenomena. Lastly, planar bleeding occurs when regions of two planes coexist; such phenomena are usually short-lived, and disastrous for their environments.

Planar pathways

editPlanar pathways are special landscape features appearing in multiple planes or layers of a plane. Travel along a planar pathway results in travel along the planes. Pathways are crucial tactically, because they are very stable compared to portals or gates, and do not require magic spells or portal keys. One notable planar pathway in the Planescape campaign setting is the River Styx, which flows across the Lower Planes and parts of the Astral Plane. Another is the River Oceanus, which flows through the Upper Planes.

River Oceanus

editThe first edition Manual of the Planes describes the River Oceanus as one of the features of the Outer Planes, which "links the planes of Elysium, Happy Hunting Grounds, and Olympus in much the same way that the Styx links the lower planes". The river disappears and reappears a number of times in different layers of the planes, but it seems to follow a course that begins in Thalasia, the third layer of Elysium, flows through the second and first layers of that plane, then across the topmost layer of the Happy Hunting Grounds, then into the topmost layer of Olympus to its final rest in the second layer of that plane, Ossa. The Oceanus is a more natural river than the Styx, and no harm comes to those who drink of it. The Oceanus does still pose all the normal dangers of a large river, and does not have the supernatural boatmen of the Styx.[55]: 84

The book goes on to describe how Oceanus appears on specific Outer Planes. The first four layers of the plane of Elysium "are dominated by the River Oceanus, which begins in the fourth (outermost) layer of this plane and flows down to the innermost layer (the layer nearest the Astral). From there Oceanus meanders into the Happy Hunting Grounds and then into the innermost layer of Olympus." These three good planes are linked by the Oceanus in the same manner as the lower planes are linked by the River Styx. By contrast, the Oceanus is a slow, peaceful flow, navigable by mere mortals (though its peaceful flow is often broken by rapids, cascades, waterfalls, and occasional fallen trees). The river separates and recombines many times in its passage, so travelers often find themselves journeying down side channels that soon rejoin the main stream. A traveler on the Oceanus can usually reach another layer by traveling downstream (or upstream, for the flow doubles back several times).[55]: 90 The Egyptian goddess Isis holds sway over a large realm of the layer of Amoria, including several paths of the Oceanus. The god Seker and his moveable realm Ro Stau spend most of their times adjacent to Isis's realm on the Oceanus. The Sumerian moon god Nanna-Sin travels the Oceanus in a great barque that is shaped like a crescent moon; in passing he provides a moon-like radiance to all on the banks of the river.[55]: 91 Krigala is the first layer of the plane of the Happy Hunting Grounds, closest to the Astral, and through it the Oceanus flows in a relatively straight course (compared to its winding through Elysium) into Olympus.[55]: 91 Ossa, the second layer of the plane of Olympus, is the outflow of the river Oceanus. There are often reports of huge, funnel-like maelstroms that lead directly back to Thalasia in an unending circle.[55]: 93

River Styx

editThe first edition Monster Manual II mentions that the River Styx "links the topmost layers of the Lower Planes, and its branches can be found anywhere from the Nine Hells to the Abyss". The river is a deep, swift, and unfordable torrent. Creatures coming into contact with the waters of the Styx instantly forget their entire past lives. The safest passage is by the skiff of Charon, boatman of the Lower Planes. Charon may be summoned only on the banks of the Styx, and he will appear with a large black skiff, and if requested he will ferry travelers to the topmost layer of any Lower Plane for a price.[56]: 28 The charonadaemons are the servants of Charon, and pilot small skiffs along the Styx. Charonadaemons are normally found anywhere on the Styx and charge travelers a price to pilot their craft through the Astral and Ethereal planes as well as the Lower Planes.[56]: 29 The first edition Manual of the Planes describes the River Styx as a means to travel from one Outer Plane to another, noting that "it flows through many portals in the lower planes and provides a regularly-used highway through these planes."[55]: 77 The River Styx reappears in sourcebooks such as the Planescape Campaign Setting (1994),[57] Planes of Chaos (1994),[58] Planes of Law (1995),[59] and the 3rd Edition Manual of the Planes (2001).[60]

Yggdrasil

editThe first edition Manual of the Planes describes Yggdrasil as an astral landmark, noting that it is normally encountered by travelers from worlds that worship the Norse mythoi, but travelers from other Prime Material worlds can encounter the tree. It is a long-standing conduit from the Outer Planes to alternate prime worlds that was created by a group of deities and worshippers in the Prime Material plane. Yggdrasil is the "World Ash" that links several outer planes to the Prime Material plane, in the Norse mythos. It runs from Gladsheim, home of most of the Norse mythos, to Nifflheim, the center layer of the three Glooms of Hades and the dwelling place of the goddess of the same name. Roots and branches of Yggdrasil wind through most of the Prime worlds where these deities are recognized. The tree is a solid and permanent conduit that weathers the waxing and waning of faiths in the Prime Material and the fortunes of gods in the outer planes. The traveler is confronted with a huge tree rising from the mist of the Astral and disappearing far into the distance. The traveler can then climb the tree to the appropriate outer plane, descend to the reachable lower planes, or explore the alternate Prime worlds that the conduits touch upon. At the true terminus, the tree ends in a color pool similar to that of a fixed portal. The traveler can then pass into the outer plane as if moving into an alternate Prime Material or the Astral plane. Yggdrasil and Mount Olympus are the best-known of the permanent conduits that link the outer planes with the Prime and with other nonlinear outer planes.[55]: 72 Magical interplanar portals generally only appear in the top layer of the outer planes, although some free-standing portals that pass through the Astral, like the Yggdrasil, pierce the lower reaches of some planes.[55]: 77 The apertures that the Yggdrasil causes in the Prime worlds are fixed and limited to those places where the Norse gods are known.[55]: 95

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d Lord Winfield (September–October 1997). "Planescape – un bon plan". Backstab (in French). 5: 46–47. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Carbonell, Curtis D. (2019). Dread Trident: Tabletop Role-Playing Games and the Modern Fantastic. Liverpool. ISBN 978-1-78962-468-7. OCLC 1129971339.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e Appelcline, Shannon (April 23, 2015). "An Elementary Look at the Planes". Wizards of the Coast. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Gearing up for Eberron: The World of Eberron". Archived from the original on April 1, 2004.

- ^ a b c d Appelcline, Shannon. "Manual of the Planes (1e) | Product History". Dungeon Masters Guild. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Gygax, Gary (July 1977). "Planes: The Concepts of Spatial, Temporal and Physical Relationships in D&D". The Dragon. Vol. I, no. 8. TSR. p. 4.

- ^ Gygax, Gary (1978). Players Handbook (1st ed.). TSR. ISBN 0-935696-01-6.

- ^ Davis, Graeme (November 1986). "Open Box". White Dwarf (review) (83). Games Workshop: 2.

- ^ Appelcline, Shannon. "OP1 Tales of the Outer Planes (1e) | Product History". Dungeon Masters Guild. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Planescape Torment Preview". August 6, 2003. Archived from the original on August 6, 2003.

- ^ Perlini-Pfister, Fabian (2012). "Philosophers with Clubs: Negotiating Cosmology and Worldviews in Dungeons & Dragons". Religions in Play: Games, Rituals, and Virtual Worlds. Philippe Bornet. Zürich: Pano-Verlag. pp. 275–294. ISBN 978-3-290-22010-5. OCLC 779127134.

- ^ Kulp, Kevin. "Manual of the Planes (3e) | Product History". Dungeon Masters Guild. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Appelcline, Shannon. "Manual of the Planes (4e) | Product History". www.dmsguild.com. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b Faul, Matt (December 6, 2011). "Tabletop Review: Dungeons & Dragons – Player's Option: Heroes of the Feywild & Fury of the Feywild Fortune Cards". Diehard GameFAN. Retrieved September 9, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Dungeons & Dragons: A Guide to the Planes". CBR. April 5, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Says, Michael Christensen (February 17, 2015). "Planes Update". World Builder Blog.

- ^ "Dungeons & Dragons Outer Planes & Afterlives Explained". ScreenRant. May 15, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "D&D: A Beginner's Guide To The Multiverse". TheGamer. August 22, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "D&D: 10 Outer Planes To Add To Your Next Campaign". CBR. June 20, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ "Monsters (G)". Archived from the original on September 16, 2003.

- ^ "Planes". Archived from the original on July 24, 2003.

- ^ "Spells (D-E)". Archived from the original on September 16, 2003.

- ^ Alloway, Gene (May 1994). "Feature Review: Planescape". White Wolf (43). White Wolf Publishing: 36–38.

- ^ Kaneda (May–June 1998). "Monstrous Compendium Planescape Appendix III". Backstab (in French). 9: 32. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ "Dungeons & Dragons Elemental Inner Planes Explained". ScreenRant. May 15, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Rolston, Ken (February 1990). "Role-playing Reviews". Dragon (#154). Lake Geneva, Wisconsin: TSR: 59–63.

- ^ Lucard, Alex (August 11, 2014). "Ten Things You Might Not Know About the Dungeons & Dragons Fifth Edition Player's Handbook (Dungeons & Dragons/D&D Next)". Diehard GameFAN. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Five Facts Critical Role Fans Need To Know About the Feywild". Nerdist. July 14, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Hall, Charlie (September 8, 2021). "Chonky fairies and sassy rabbitfolk are coming to Dungeons & Dragons". Polygon. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ a b c Grebey, James (June 7, 2021). "Dungeons & Dragons' next book is a wicked, whimsical exploration into the Feywild". SYFY WIRE. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Chris Perkins Interview: D&D's The Wild Beyond The Witchlight". ScreenRant. September 7, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ Cappellini, Matt (November 30, 2000). "Blockbusters Make Christmas Bright". The Beacon News. Aurora, Illinois. Archived from the original on June 29, 2014. Retrieved November 21, 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Webb, Trenton (January 1997). "Games Reviews". Arcane. No. 15. p. 68.

- ^ Grubb, Jeff, David Noonan, and Bruce Cordell. Manual of the Planes (Wizards of the Coast, 2001)

- ^ Jeff Grubb, Manual of the Planes (TSR, 1987).

- ^ a b Jacobs, James. "The Shadow Over D&D", Dragon No. 324 (Wizards of the Coast, October 2004).

- ^ a b c Cordell, Bruce R. "Enter the Far Realm", Dragon No. 330 (Wizards of the Coast, April 2005)

- ^ a b Shannon (2011). Designers & Dragons. Mongoose Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-907702-58-7.

- ^ Cordell, Bruce. The Gates of Firestorm Peak (TSR, 1996).

- ^ Heinsoo, Rob, Collins, Andy and Wyatt, James. Player's Handbook (Wizards of the Coast, 2008), ISBN 978-0-7869-4867-3.

- ^ a b "Manual of the Planes Excerpts: Types of Planes". Wizards of the Coast. November 17, 2008. Archived from the original on June 3, 2009.

- ^ "Manual of the Planes" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 2, 2009.

- ^ "The City of Brass". Archived from the original on December 3, 2008.

- ^ Witwer, Michael; Newman, Kyle; Peterson, Jonathan; Witwer, Sam; Manganiello, Joe (October 2018). Dungeons & Dragons Art & Arcana: a visual history. Ten Speed Press. pp. 85–87, 244–245. ISBN 9780399580949. OCLC 1033548473.

- ^ Manual of the Planes (2008)

- ^ "Tabletop Review: Dungeons & Dragons – Player's Option: Heroes of the Feywild & Fury of the Feywild Fortune Cards – Diehard GameFAN 2018". December 6, 2011.

- ^ "Black Gate » Articles » Join the Heroes of the Feywild". February 27, 2012.

- ^ "Dungeons & Dragons Releases Domains of Delight Supplement". ComicBook.com. September 21, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "Dungeons & Dragons' Feywild Now Has Domains Of Delight". ScreenRant. July 16, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2021.

- ^ "Dungeons & Dragons: Why the Shadowfell Is So Dangerous". CBR. April 5, 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- ^ Appelcline, Shannon. "An Elementary Look at the Planes". Wizards of the Coast. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2015.

- ^ Rea, Nicky. Defilers and Presrevers: Wizards of Athas. TSR, Inc., 1996.

- ^ Appelcline, Shannon. "Defilers and Preservers: The Wizards of Athas (2e)". dndclassics.com. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ excerpt from Chapter 5 of the Eberron Campaign Setting.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Grubb, Jeff. Manual of the Planes (TSR, 1987)

- ^ a b Gygax, Gary. Monster Manual II (TSR, 1983)

- ^ Cook, David "Zeb". Planescape Campaign Setting. (TSR, 1994)

- ^ Smith, Lester, and Wolfgang Baur. Planes of Chaos. (TSR, 1994)

- ^ McComb, Colin, and Wolfgang Baur. Planes of Law. (TSR, 1995)

- ^ Grubb, Jeff, David Noonan, and Bruce Cordell. Manual of the Planes (Wizards of the Coast, 2001)

- Cook, David (1989). Player's Handbook. TSR. ISBN 0-88038-716-5.

- Cordell, Bruce R; Gwendolyn F.M. Kestrel (2004). Planar Handbook. Wizards of the Coast. ISBN 0-7869-3429-8.

- Grubb, Jeff (1987). Manual of the Planes. TSR. ISBN 0-88038-399-2.

- Grubb, Jeff; Cordell, Bruce R.; Noonan, David (2001). Manual of the Planes. Wizards of the Coast. ISBN 0-7869-1850-0.

- Ward, James M; Kuntz, Robert J. (1980). Deities & Demigods. TSR. ISBN 0-935696-22-9.

External links

edit- Plane of existence, D&D Glossary