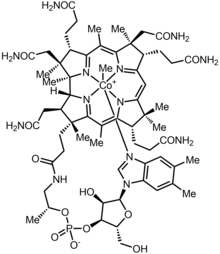

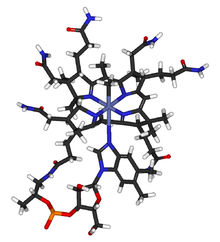

Methylcobalamin (mecobalamin, MeCbl, or MeB12) is a cobalamin, a form of vitamin B12. It differs from cyanocobalamin in that the cyano group at the cobalt is replaced with a methyl group.[1] Methylcobalamin features an octahedral cobalt(III) centre and can be obtained as bright red crystals.[2] From the perspective of coordination chemistry, methylcobalamin is notable as a rare example of a compound that contains metal–alkyl bonds. Nickel–methyl intermediates have been proposed for the final step of methanogenesis.

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Cobolmin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | International Drug Names |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, sublingual, injection. |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.033.200 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C63H91CoN13O14P |

| Molar mass | 1344.405 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Methylcobalamin is equivalent physiologically to vitamin B12,[3][non-primary source needed] and can be used to prevent or treat pathology arising from a lack of vitamin B12 intake (vitamin B12 deficiency).[medical citation needed][dubious – discuss]

Methylcobalamin is also used in the treatment of peripheral neuropathy, diabetic neuropathy, and as a preliminary treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[4]

Methylcobalamin that is ingested is not used directly as a cofactor, but is first converted by MMACHC into cob(II)alamin. Cob(II)alamin is then later converted into the other two forms, adenosylcobalamin and methylcobalamin for use as cofactors. That is, methylcobalamin is first dealkylated and then regenerated.[5][6][7]

The efficacy of methylcobalamin administration in treating vitamin B12 deficiency remains uncertain. While directly providing active cobalamin forms to deficient patients is an attractive approach promoted by the manufacturers of methylcobalamin products, it is not known whether methylcobalamin can reach its intracellular targets in its original, unmodified form to function effectively as ready coenzyme. It is also not known whether current level of evidence sufficient to recommend this relatively expensive strategy as an alternative to cyanocobalamin or hydroxocobalamin. There is currently insufficient evidence on comparative effectiveness and safety of various B12 vitamers (methylcobalamin, cyancobalamin, hydroxocobalamin, adenosylcobalamin).[8][9][10]

Production

editMethylcobalamin can be produced in the laboratory by reducing cyanocobalamin with sodium borohydride in alkaline solution, followed by the addition of methyl iodide.[2]

Functions

editThis vitamer, along with adenosylcobalamin, is one of two active coenzymes used by vitamin B12-dependent enzymes and is the specific vitamin B12 form used by 5-methyltetrahydrofolate-homocysteine methyltransferase (MTR), also known as methionine synthase.[citation needed]

Methylcobalamin participates in the Wood-Ljungdahl pathway, which is a pathway by which some organisms utilize carbon dioxide as their source of organic compounds. In this pathway, methylcobalamin provides the methyl group that couples to carbon monoxide (derived from CO2) to afford acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA is a derivative of acetic acid that is converted to more complex molecules as required by the organism.[11]

Methylcobalamin is produced by some bacteria.[citation needed] It plays an important role in the environment, where it is responsible for the biomethylation of certain heavy metals. For example, the highly toxic methylmercury is produced by the action of methylcobalamin.[12] In this role, methylcobalamin serves as a source of "CH3+".

A lack of cobalamin can lead to megaloblastic anemia and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord.[13]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ McDowell LR (2000). Vitamins in animal and human nutrition. Wiley. ISBN 978-0813826301. Retrieved 28 January 2018 – via Booksgoogle.com.

- ^ a b David D (January 1971). "Preparation of the Reduced Forms of Vitamin B12 and of Some Analogs of the Vitamin B12 Coenzyme Containing a Cobalt-Carbon Bond". In McCormick DB, Wright LD (eds.). Vitamins and Coenzymes. Methods in Enzymology. Vol. 18. Academic Press. pp. 34–54. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(71)18006-8. ISBN 9780121818821.

- ^ Sil A, Kumar H, Mondal RD, Anand SS, Ghosal A, Datta A, et al. (July 2018). "A randomized, open labeled study comparing the serum levels of cobalamin after three doses of 500 mcg vs. a single dose methylcobalamin of 1500 mcg in patients with peripheral neuropathy". The Korean Journal of Pain. 31 (3): 183–190. doi:10.3344/kjp.2018.31.3.183. PMC 6037815. PMID 30013732.[non-primary source needed]

- ^ "Eisai Submits New Drug Application for Mecobalamin Ultra-High Dose Preparation as Treatment for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Japan" (PDF). Eisai.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Kim J, Hannibal L, Gherasim C, Jacobsen DW, Banerjee R (November 2009). "A human vitamin B12 trafficking protein uses glutathione transferase activity for processing alkylcobalamins". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 284 (48): 33418–33424. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.057877. PMC 2785186. PMID 19801555.

- ^ Hannibal L, Kim J, Brasch NE, Wang S, Rosenblatt DS, Banerjee R, et al. (August 2009). "Processing of alkylcobalamins in mammalian cells: A role for the MMACHC (cblC) gene product". Molecular Genetics and Metabolism. 97 (4): 260–266. doi:10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.04.005. PMC 2709701. PMID 19447654.

- ^ Froese DS, Gravel RA (November 2010). "Genetic disorders of vitamin B₁₂ metabolism: eight complementation groups–eight genes". Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine. 12: e37. doi:10.1017/S1462399410001651. PMC 2995210. PMID 21114891.

- ^ Thakkar K, Billa G (January 2015). "Treatment of vitamin B12 deficiency – Methylcobalamine? Cyancobalamine? Hydroxocobalamin? – clearing the confusion". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 69 (1): 1–2. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2014.165. PMID 25117994.

- ^ Obeid R, Fedosov SN, Nexo E (28 March 2015). "Cobalamin coenzyme forms are not likely to be superior to cyano- and hydroxyl-cobalamin in prevention or treatment of cobalamin deficiency". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 59 (7): 1364–1372. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201500019. PMC 4692085. PMID 25820384.

- ^ Obeid R, Andrès E, Češka R, Hooshmand B, Guéant-Rodriguez R, Prada GI, et al. (10 April 2024). "Diagnosis, Treatment and Long-Term Management of Vitamin B12 Deficiency in Adults: A Delphi Expert Consensus". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 13 (8): 2176. doi:10.3390/jcm13082176. PMC 11050313. PMID 38673453.

- ^ Fontecilla-Camps JC, Amara P, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y, Volbeda A (August 2009). "Structure-function relationships of anaerobic gas-processing metalloenzymes". Nature. 460 (7257): 814–822. Bibcode:2009Natur.460..814F. doi:10.1038/nature08299. PMID 19675641. S2CID 4421420.

- ^ Schneider Z, Stroiński A (1987), Comprehensive B12: Chemistry, Biochemistry, Nutrition, Ecology, Medicine, Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3110082395

- ^ Bémeur C, Montgomery JA, Butterworth RF (2011). "Vitamins Deficiencies and Brain Function". In Blass JP (ed.). Neurochemical Mechanisms in Disease. Advances in Neurobiology. Vol. 1. pp. 103-124 (112). doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-7104-3_4. ISBN 978-1-4419-7103-6.