St Edmund's College, Cambridge

St Edmund's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge[4] in England. Founded in 1896, it is the second-oldest of the three Cambridge colleges oriented to mature students, which accept only students reading for postgraduate degrees or for undergraduate degrees if aged 21 years or older.

| St Edmund's College | |

|---|---|

| University of Cambridge | |

St Edmund's College Chapel and the original Norfolk Building | |

Arms of St Edmund's College Arms: Arms of Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk (quarterly of four: Howard, Brotherton, Warenne, FitzAlan) with a canton of St Edmund of Abingdon (Or, a cross fleury gules between four Cornish choughs proper[1]) all within a bordure argent | |

| Scarf colours: blue, with two equally-spaced narrow stripes of Cambridge blue edged with white | |

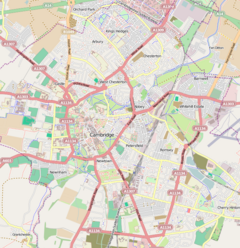

| Location | Mount Pleasant, Cambridge (map) |

| Full name | The Master, Fellows and Scholars of St Edmund’s College in the University of Cambridge |

| Latin name | Collegium Sancti Edmundi |

| Abbreviation | ED[2] |

| Motto | Per Revelationem et Rationem (Latin) |

| Founders | |

| Established | 1896 |

| Named after | Edmund of Abingdon |

| Previous names | St Edmund's House |

| Age restriction | 21 and older |

| Sister college | Green Templeton College, Oxford |

| Master | Chris Young |

| Undergraduates | 188 (2022-23) |

| Postgraduates | 528 (2022-23) |

| Endowment | £18.1m (2019)[3] |

| Visitor | Vincent Nichols, Archbishop of Westminster |

| Website | www |

| CR | www |

| Map | |

Named after St Edmund of Abingdon (1175–1240), who was the first known Oxford Master of Arts and Archbishop of Canterbury from 1234 to 1240, the college has Catholic roots. Its founders were Henry Fitzalan-Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, and Baron Anatole von Hügel (1854–1928), the first Catholic to take a Cambridge degree since the deposition of King James II in 1688.[5] The Visitor is the Archbishop of Westminster (at present Cardinal Vincent Nichols).[6]

The college is located on Mount Pleasant, northwest of the centre of Cambridge, near Lucy Cavendish College, Murray Edwards College and Fitzwilliam College. Its campus consists of a garden setting on the edge of what was Roman Cambridge, with housing for over 350 students.

Members of St Edmund's include cosmologist and Big Bang theorist Georges Lemaître, Norman St John-Stevas, Archbishop Eamon Martin, of Armagh, Bishop John Petit of Menevia, and Olympic medalists Simon Schürch (Gold), Thorsten Streppelhoff (Silver), Marc Weber (Silver), Stuart Welch (Silver) and Simon Amor (Silver). St Edmund's was the residential hall of the university's first Catholic students in 200 years – most of whom were studying for the priesthood – after the lifting of the papal prohibition on attendance at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in 1895 at the urging of a delegation to Pope Leo XIII led by Baron von Hügel.[7]

History

editFoundation

editSt Edmund's House was founded in 1896 by Henry Fitzalan-Howard, the 15th Duke of Norfolk, and Baron Anatole von Hügel as an institution providing board and lodging for Roman Catholic students at the University of Cambridge.

After Catholic Emancipation, in particular after the Universities Tests Act 1871, students who were Roman Catholics were admitted as members of Oxford and Cambridge universities. However, the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith decreed that it would be next to impossible for the ancient English universities to be frequented without mortal sin, stressing the dangers of an increasing atmosphere of liberalism and scepticism.[8] This decision was met with public outcry from the wealthy laity, who wished for their sons to attend Oxbridge colleges.[9] After a petition led by Anatole von Hügel, this ban was lifted in 1895 by Pope Leo XIII with the condition that a chaplain be appointed, a library with Catholic books be founded, and public lectures on philosophy, history and religion be established.[10][11] As a result, the Universities Catholic Education Board (later Oxford and Cambridge Catholic Education Board) was founded and Edmund Nolan was appointed Chaplain. The Duke of Norfolk purchased property in Cambridge and the Cambridge University Catholic Chaplaincy was established at St Edmund's House in November 1886.[10]

In its early days the college functioned predominantly as a lodging house, or hall of residence, for students who were matriculated at other colleges. Most of the students, at that time, were ordained Catholic priests who were reading various subjects offered by the University. The college was established in the buildings of Ayerst Hostel, which had been set up for non-collegiate students by the Anglican priest William Ayerst in 1884.[7] In 1896 Ayerst Hostel closed due to lack of funds, and the property was transferred to the Catholic Church.[12] The founding master of St Edmund's House was Edmund Nolan, then vice-rector of St Edmund's College, Ware.[7]

Collegiate Status

editAttempts to have St Edmund's House become a constituent college of the University of Cambridge were undertaken at various junctures, but were met in pre-ecumenical days by continuing opposition from the predominantly Protestant membership of the university’s governing Regent House. Among motives cited were that the college was not self-governing and its assets were held in trust by an external body, namely, the Catholic Church.[13]

The chapel was consecrated in 1916 by Cardinal Francis Bourne, Archbishop of Westminster.[14] A new dining hall was constructed in 1939 and the membership of the college increased steadily as it became a recognised House of Residence of the university, without college status.

In response to growing postgraduate student numbers in the early 1960s, the Regent House of the university established several Colleges primarily for postgraduate students, and St Edmund's House became one of the graduate Colleges in the University (the others being Wolfson College, Hughes Hall, Clare Hall and Darwin College). This spurred further progress regarding St Edmund's status within the University, and in 1965, the College was permitted to matriculate its own students and new fellows were elected. In 1975 St Edmund's acquired the status of an "Approved Foundation", and after the transfer of the College assets from the Catholic Church to the autonomous governing body comprising the Masters and Fellows of the College in 1986, the College changed its name from "St Edmund's House" to "St Edmund's College". It received university approval for full collegiate status in 1996, and this was confirmed by the grant of its royal charter in 1998.[15][16] The college now accepts students of all faiths and none.

Allegations of Misconduct

editNoah Carl racism controversy

editSt Edmund’s College faced backlash over its handling of Noah Carl's appointment, following revelations about his research promoting links between race, intelligence, and criminality. An investigation led to his dismissal, citing ethical and scholarly shortcomings. However, the college had failed to vet his background thoroughly and acted only under pressure from public protests.[17] The college dismissed Carl as there "There was a serious risk that Dr Carl’s appointment could lead, directly or indirectly, to the college being used as a platform to promote views that could incite racial or religious hatred, and bring the college into disrepute".[18] While the college maintained it upheld academic standards, its approach to the recruitment and eventual dismissal drew criticism for lack of transparency and effective oversight.[19]

Accusations of Hinduphobia

editIn March 2023, the college faced accusations of Hinduphobia after Hindu students were criticised for unintentionally colouring a statue during Holi. The CR president was forced by college fellows to issue an apology despite believing no harm was intended. The college was seen by many students to have overstepped their authority, by interfering with the CR’s independence, and to have alienated Hindu students at the college.[20]

Buildings and grounds

editNorfolk Building

editThe Norfolk Building is the oldest building on site, dating back to 1896 as the former Ayerst Hostel; it provided accommodation for Edmund Nolan, the first Master of St Edmund's, along with the first four students of the college.[21] Known for its clean Gothic revival style, the building underwent a three-phase extension scheme designed by Roderick Gradidge in 1989, and now houses amenities including the Combination Room, Dining Hall, Kitchens and a Porter's office.[22]

Chapel

editThe chapel is a Grade II listed building designed by the architect Benedict Williamson CSSP and was consecrated by Cardinal Francis Bourne, Archbishop of Westminster in 1916.[14] Notable for its simplicity and Gothic Revival architecture, the chapel is a Catholic foundation, although it is open to members of other Christian denominations.[23] In 2003, a stained-glass window depicting the ministry of Saint Boniface of Crediton (c. 675 - 754 AD), the apostle to Germany, was donated by Stephen Frowen and blessed by Cardinal Cormac Murphy-O'Connor, Archbishop of Westminster.[23]

A bronze sculpture of the college patron, St Edmund of Abingdon, is located at the front of the chapel, his left hand holding a Bible. The statue is the work of Rodney Munday, an alumnus of St Edmund Hall, Oxford, and was commissioned by the College in 2007.[23] The Chapel Schola and Choir perform in concerts in collaboration with St Edmund Hall, Oxford and St Edmund's College, Ware in commemoration of their Patron Saint.

Expansion

editSt Edmund's continues to expand and develop its buildings. In 2000, a new residential building housing 50 students was opened, named after Richard Laws, one of the former Masters. In 2006, two new residential buildings, including rooms for 70 students as well as apartments for couples, were opened; these were named after the former Master of the College, Sir Brian Heap, and the former Vice-Master, Geoffrey Cook.

In 2016, major plans were announced for the development of two new courts and several buildings. It was planned that brick buildings would form the perimeter of two new courts and a new multi-million pound student centre will frame the west side of the College. The expansion plans received planning consent from Cambridge City Council in June 2017, but building work never started.[24][circular reference]

Okinaga Tower

editCreated in 1993 by the bequest of the Teikyo Foundation, the Okinaga Tower is the college's tallest structure. Designed by architect Roderick Gradidge in 1989 it houses the Master's Lodge, as well as a suite with views of the city and was opened by Betty Boothroyd, Speaker of the House of Commons.[22]

Courts and other buildings

editThe Brian Heap, Richard Laws, Geoffrey Cook and the Luizo buildings were constructed to accommodate growing student numbers in the 2000s, with most buildings providing are student dormitories.

In 2019 the college constructed Mount Pleasant Halls, occupying the site of a substantial office block formerly on the site and giving St Edmund College a frontage to the main thoroughfare of Huntington Road.

The College Sporting Grounds is located west of the Richard Laws Building, and offers a full-sized football pitch for college sports and other outdoor activities.

The College Orchard is south of the Sporting Grounds, and consists of a small lawn with 5 apple trees, outdoor seating, and a barbecue pit for students.

White Cottage is a modest 18th-century brick farmhouse which pre-dates the college buildings on the site and is painted white, situated adjacent to Mount Pleasant Halls against which it appears an incongruous survival. White Cottage was the first home of the Von Hugel Institute, a Catholic Institute for Critical Enquiry working in the fields of Christianity and society. The Institute was founded in 1987 to preserve the Roman Catholic legacy of the College when control of the College itself was ceded to its autonomous Governing Body in 1985 in order to achieve university collegiate status.[25]

Bene't House is a detached Edwardian house, south-east of the Norfolk Old Wing. Named after St Benedict of Nursia (c.480 - 547 AD), it has since 2018 contained the facilities and offices for the Von Hugel Institute.[25]

Gallery

edit-

Mount Pleasant Halls front facade

-

Mount Pleasant Halls Court

-

Main gate

-

Sporting grounds and Brian Heap Building

-

Richard Laws Building

-

Geoffrey Cook Building

-

College orchards

-

Maisonettes, now used as offices

-

Norfolk Extension

-

Bene't House

-

College Chapel

Academic profile

editThe full spectrum of academic subjects is represented in the college. The fellowship of the college represents many academic disciplines, spread across arts, humanities, social sciences, natural sciences, medicine, and veterinary medicine.

The college has one research institute attached to it: the Von Hügel Institute founded in 1987 to carry out research on Catholic Social Teaching. Describing itself as a 'Catholic Institute for Critical Enquiry' it works in the fields of Christianity and society, and seeks to preserve the Roman Catholic legacy of St Edmund's College when control of the College itself was ceded to its autonomous Governing Body in 1985 in order to achieve university collegiate status.[25] The Von Hügel Institute is therefore a link to the Roman Catholic origins of the college.

The overall examination results of the college's comparatively few undergraduates tend to be in the middle among the Cambridge colleges, with St Edmund's ranking 21st on the Tompkins table in 2018.[26]

Student life

editThe college is younger than some of the more traditional colleges of the university. Despite this St Edmund's maintains many ancient Cambridge traditions including formal hall, albeit with modifications. Fellows at most Cambridge and Oxford colleges dine at a "high table" (separately from the students); however, St Edmund's has no such division, with undergraduates, postgraduates and fellows sitting together at dinners.[27] Unlike most mature and modern colleges, St Edmund's still requires students to wear their academic gowns during formal halls, ceremonies, and college occasions. St Edmund's retains several other dining traditions unusual for modern colleges, including a requirement to ask the master to leave the hall to use the bathroom, a banning of technological devices and newspapers, and a strict requirement to only speak English.[28] The St Edmund's undergraduate gown is fashioned from distinctive black cloth with close detailing around the neck and sleeves.

The college has a long sporting tradition, including the St Edmund's College Boat Club, the St Edmund's College Hockey Club (SECHC) and the St Edmund's College Cricket Club (SECCC). SECHC (merged with St Catherine's College Hockey Club) won 2024 Cuppers and SECCC reached the 2023 Cuppers finals. In recent years members have competed in varsity teams representing Cambridge against Oxford University in a wide variety of sports, most notably, at The Boat Race, The Varsity Match,[29] the University Match (hockey) and The University Match (cricket).[30] Punts are available to students in the spring and summer months.

On 15 September 2017, a team of four rowers from the college broke the World record for the 'Longest Continual Row' in the male 20-29 small team category by over an hour.[31] The following year, on 13 April 2018, a team of ten rowers from the college went on to set the British and World record for "One Million Meters" on the indoor rowing machine in the male 20-29 large team category.[32][33]

People associated with the college

edit-

Catherine Arnold OBE, former Master of St Edmund's College and former British Ambassador to Mongolia

-

Chito Gascon, Chair of the Human Rights Commission of the Philippines

-

Mary McAleese, former President of Ireland

-

Martin Evans, biologist and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

Alumni

edit- Edward Acton, Vice-Chancellor of the University of East Anglia, historian and great-grandson of Lord Acton

- Joaquín Almunia, Spanish politician and member of the European Commission responsible for Economic and Monetary Affairs

- Simon Amor, rugby union coach, member of the England Sevens team at the 2002 Commonwealth Games

- Malcolm Baker, Robert G. Kirby Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, former Olympic rower

- Johan Bäverbrant, Swedish diplomat

- Aidan Bellenger, historian and former Benedictine monk

- Alexander Bird, Bertrand Russell Professor of Philosophy at the University of Cambridge

- William T. Cavanaugh, director of the Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural Theology, and professor of Catholic studies at DePaul University

- James Chau, Journalist, television presenter, and United Nations goodwill ambassador

- Christian Cormack, rowing cox

- Captain Sir George Sampson Elliston, Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Blackburn from 1931 to 1945

- Chito Gascon, Chair of the Human Rights Commission of the Philippines

- Alex Hughes, Archdeacon of Cambridge

- John M. Jumper, AI researcher and Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry in 2024

- Hilary Lofting, Australian novelist, travel writer, journalist and editor. Eldest brother of Hugh Lofting (author of The Story of Doctor Dolittle).

- Louise Lombard, actress[34]

- Greg Loveridge, former cricketer who played for New Zealand in 1996

- Eamon Martin, Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of All Ireland

- Rodrigo Rosenberg Marzano, Guatemalan attorney and human rights activist

- Alexander Masters, author, screenwriter, and worker with the homeless. Masters was portrayed by Benedict Cumberbatch in Stuart: A Life Backwards.

- Anna Mendelssohn, writer, poet, and political activist

- Robert Noel, Officer of Arms (herald) at the College of Arms

- Chris Oti, former rugby union player

- Richard Phelps (rower), rower who competed in the 1992 Summer Olympics

- Norman St John-Stevas, Baron St John of Fawsley, legal scholar, former master of Emmanuel College, and Leader of the House of Commons under Margaret Thatcher was a resident at St Edmund's House for his undergraduate studies in late 1940s and early 1950s. During his time he was the president of the Union Society

- Christopher Stearn, former first-class cricketer

- Thorsten Streppelhoff, Olympic Silver medalist and German M8+ rower at the 1996 Atlanta and 1992 Barcelona Games

- Tony Underwood, rugby union international

- David Wallace, scholar of medieval literature, Judith Rodin Professor of English at the University of Pennsylvania

- Patrick Walsh, Irish prelate of the Roman Catholic Church and from 1991 until 2008 he was the 31st bishop of Down & Connor

- Luke Walton, American Olympic rower

- Marc Weber, Olympic Silver medalist and German M8+ rower at the 1996 Summer Olympics

- Stuart Welch, Olympic Silver medalist and Australian M8+ rower at the 2000 Summer Olympics

Fellows

edit- Denis Alexander, Emeritus Fellow of St Edmund’s College and an Emeritus Director of the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion, Cambridge

- Allen Brent, scholar of early Christian history and literature

- Noah Carl, Sociologist and race-intellegence researcher, later dismissed for bringing the college into disrepute [35]

- Sir Martin Evans FRS FMedSci, Laureate of the 2007 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

- Andy Harter, computer scientist

- Sir Brian Heap, biologist who was the master of the college from 1996 until 2004. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society in 1989 and held the post vice-president and foreign secretary from 1996 to 2001

- Richard Edwin Hills, emeritus professor of Radio Astronomy at the University of Cambridge

- Kevin T. Kelly, Roman Catholic priest and moral theologian

- Edward Kessler, Founder President of The Woolf Institute and a leading thinker in interfaith relations, primarily Jewish-Christian-Muslim Relations

- Ilyas Khan, technologist and businessman

- Nicholas Lash, Roman Catholic theologian

- Georges Lemaître, cosmologist and Big Bang theorist, was a visiting academic at the college in 1923–24, while collaborating with Sir Arthur Eddington

- Helen Mason, theoretical physicist

- Josef W. Meri, American historian of Interfaith Relations in the Middle East in the College of Islamic Studies, Hamad Bin Khalifa University

- Simon Mitton, astronomer and author. Elected member of the Council of the Royal Astronomical Society.

- Mark Ranby, former New Zealand rugby union player

- Chris Rapley, scientist

- Somak Raychaudhury, Indian astrophysicist

- C. J. Ryan, priest and scholar of Italian studies

- Brian Stanley, historian

- Bob White, Professor of Geophysics in the Earth Sciences department at Cambridge University (since 1989) and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1994

Honorary Fellows

edit- Bruce Alberts, American biochemist and the Chancellor’s Leadership Chair in Biochemistry and Biophysics for Science and Education at the University of California, San Francisco

- Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh

- Betty Boothroyd, Member of Parliament (MP) from 1973 to 2000, Speaker of the House of Commons

- Alec Broers, Baron Broers, electrical engineer

- Colin Bundy, South African historian, former principal of Green Templeton College, Oxford and former director of SOAS University of London

- Derek Burke, academic who served as Vice-Chancellor of the University of East Anglia

- Francis Campbell, former UK Ambassador to the Holy See

- Janet Neel Cohen, Baroness Cohen of Pimlico, lawyer and crime fiction writer

- Edward Fitzalan-Howard, 18th Duke of Norfolk, peer who holds the hereditary office of Earl Marshal

- Alan Hopes, Roman Catholic prelate

- Denise Lievesley, formerly Chief Executive of the Information Centre for Health and Social Care, Director of Statistics at UNESCO

- Mary McAleese, former President of Ireland and patron of the Von Hugel Institute

- Bridget Ogilvie, Australian and British scientist

- Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, husband of Queen Elizabeth II

- Sir Tom Phillips, diplomat who served as Commandant of the Royal College of Defence Studies from 2014 to 2018

- Anthony Russell, Anglican bishop

- Amartya Sen, laureate of the 1998 Nobel Prize in Economics

- Peter Smith, Metropolitan Archbishop of Southwark (London)

- Crispin Tickell, diplomat, environmentalist, and academic

List of Masters of St Edmund's College

editSt Edmund's House

- 1897–1904: William Ormond Sutcliffe

- 1904–1909: Edmund Nolan

- 1909–1918: Thomas Leighton Williams

- 1918–1921: Joseph Louis Whitfield

- 1921–1929: John Francis McNulty

- 1929–1934: Cuthbert Leonard Waring

- 1934–1946: John Edward Petit

- 1946–1964: Raymond Corboy

- 1964–1976: Garrett Daniel Sweeney

- 1976–1985: John Coventry

- 1985–1996: Richard Laws

St Edmund's College

- 1996–2004: Brian Heap

- 2004–2014: Paul Luzio

- 2014–2019: Matthew Bullock

- 2019–2024: Catherine Arnold

- 2024–present: Chris Young

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Shown here erroneously as French martlets gules

- ^ University of Cambridge (6 March 2019). "Notice by the Editor". Cambridge University Reporter. 149 (Special No 5): 1. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ "Accounts for the year ended 30 June 2019" (PDF). St Edmund's College, Cambridge. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Walker, Timea (21 January 2022). "St Edmund's College". www.undergraduate.study.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ lr387@cam.ac.uk (15 January 2014). "Baron Anatole von Hügel – Von Hügel Institute". www.vhi.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "St Edmund's College - University of Cambridge". www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ a b c lr387@cam.ac.uk (15 January 2014). "Baron Anatole von Hügel – Von Hügel Institute". www.vhi.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Evenett, H.O. Catholics and the Universities, 1850–1950.

- ^ The Letters and Diaries of John Henry Newman. Vol. 23. Oxford University Press. 1973.

- ^ a b Couve de Murville, M.N.L.; Jenkins, Philip (1983). Catholic Cambridge. Catholic Truth Society. ISBN 0-85183-494-9.

- ^ Evenett, H.O. (1946), "The Cambridge Prelude to 1895", The Dublin Review (437)

- ^ E Leedham-Green 1996 A concise history of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge University Press: 171-2.

- ^ Leader, Damian R. (April 1998). "A concise history of the University of Cambridge. By Elisabeth Leedham-Green. Pp. xiv+274 incl. endpapers, 45 plates and 5 figs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. £27.95 (cloth), £9.95 (paper). 0 521 43370 3; 0 521 43978 7". The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 49 (2): 329–380. doi:10.1017/s0022046997435832. ISSN 0022-0469.

- ^ a b "St Edmund's College - University of Cambridge". www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ "Development". www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ "St Edmund's College Cambridge - Royal Charter - 1998" (PDF). www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Bradbury, Rosie; Cook, Joe. "Controversial research fellow Noah Carl dismissed by St Edmund's". Varsity Online.

- ^ Adams, Richard (1 May 2019). "Cambridge college sacks researcher over links with far right". The Guardian.

- ^ Bradbury, Rosie; Cook, Joe. "Controversial research fellow Noah Carl dismissed by St Edmund's". Varsity Online.

- ^ Olsson, Erik. "Don't throw Holi paint on the Catholic Saint, Hindu students told". Varsity Online.

- ^ "St Edmund's College - Origins". www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b "St Edmund's College - Modern Day". www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b c "St Edmund's College - Chapel". www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ St Edmund's College, Cambridge

- ^ a b c lr387@cam.ac.uk (15 January 2014). "History – Von Hügel Institute". www.vhi.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Tompkins Table 2013: The Results". Cambridge.tab.co.uk. Archived from the original on 4 June 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ "Blue Book - Notes for Members" (PDF).

- ^ "Blue Book - Notes for Members" (PDF).

- ^ "Instagram".

- ^ "Hari Kukreja -".

- ^ "St Edmund's College rowers break world record".

- ^ "St Edmund's College - University of Cambridge".

- ^ "World 100,000 Meters".

- ^ Article in St Edmunds College Website

- ^ Adams, Richard (1 May 2019). "Cambridge college sacks researcher over links with far right". The Guardian.

Further reading

edit- Lubenow, W. C. (2008). "Roman Catholicism in the University of Cambridge: St Edmund's House in 1898". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 59 (4): 697–713. doi:10.1017/S0022046907002254.

- McClelland, V. Alan (1997). "St. Edmund's College, Ware and St. Edmund's College, Cambridge; Historical Connections and Early Tribulations". British Catholic History. 23 (3): 470–83. doi:10.1017/S0034193200005811. S2CID 163723108.

- Sweeney, Garret (1980). St Edmund's House, Cambridge: The First Eighty Years: A History. Cambridge: St Edmund's House. ISBN 978-0-95-071770-8.

- Walsh, Michael (1996). St Edmund's College, Cambridge, 1896–1996: A Commemorative History. Cambridge: St Edmund's College. ISBN 978-0-95-071771-5.