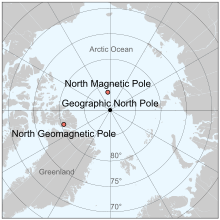

The north magnetic pole, also known as the magnetic north pole, is a point on the surface of Earth's Northern Hemisphere at which the planet's magnetic field points vertically downward (in other words, if a magnetic compass needle is allowed to rotate in three dimensions, it will point straight down). There is only one location where this occurs, near (but distinct from) the geographic north pole. The geomagnetic north pole is the northern antipodal pole of an ideal dipole model of the Earth's magnetic field, which is the most closely fitting model of Earth's actual magnetic field.

The north magnetic pole moves over time according to magnetic changes and flux lobe elongation[2] in the Earth's outer core.[3] In 2001, it was determined by the Geological Survey of Canada to lie west of Ellesmere Island in northern Canada at 81°18′N 110°48′W / 81.300°N 110.800°W.[4] It was situated at 83°06′N 117°48′W / 83.100°N 117.800°W in 2005. In 2009, while still situated within the Canadian Arctic at 84°54′N 131°00′W / 84.900°N 131.000°W,[5] it was moving toward Russia at between 55 and 60 km (34 and 37 mi) per year.[6] In 2013, the distance between the north magnetic pole and the geographic north pole was approximately 800 kilometres (500 mi).[7] As of 2021, the pole is projected to have moved beyond the Canadian Arctic to 86°24′00″N 156°47′10″E / 86.400°N 156.786°E.[8][5]

Its southern hemisphere counterpart is the south magnetic pole. Since Earth's magnetic field is not exactly symmetric, the north and south magnetic poles are not antipodal, meaning that a straight line drawn from one to the other does not pass through the geometric center of Earth.

Earth's north and south magnetic poles are also known as magnetic dip poles, with reference to the vertical "dip" of the magnetic field lines at those points.[9]

| Year | 1990 (definitive) | 2000 (definitive) | 2010 (definitive) | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North magnetic pole | 78°05′42″N 103°41′20″W / 78.095°N 103.689°W | 80°58′19″N 109°38′24″W / 80.972°N 109.640°W | 85°01′12″N 132°50′02″W / 85.020°N 132.834°W | 86°29′38″N 162°52′01″E / 86.494°N 162.867°E |

| South magnetic pole | 64°54′36″S 138°54′07″E / 64.910°S 138.902°E | 64°39′40″S 138°18′11″E / 64.661°S 138.303°E | 64°25′55″S 137°19′30″E / 64.432°S 137.325°E | 64°04′52″S 135°51′58″E / 64.081°S 135.866°E |

Polarity

editAll magnets have two poles, where lines of magnetic flux enter one pole and emerge from the other pole. By analogy with Earth's magnetic field, these are called the magnet's "north" and "south" poles. Before magnetism was well understood, the north-seeking pole of a magnet was defined to have the north designation, according to their use in early compasses. However, opposite poles attract, which means that as a physical magnet, the magnetic north pole of the Earth is actually on the southern hemisphere.[11][12] In other words, if we establish that true geographic north is north, then what we call the Earth's north magnetic pole is actually its south magnetic pole since it attracts the north magnetic pole of other magnets, such as compass needles.

The direction of magnetic field lines is defined such that the lines emerge from the magnet's north pole and enter into the magnet's south pole.

History

editEarly European navigators, cartographers and scientists believed that compass needles were attracted to a hypothetical "magnetic island" somewhere in the far north (see Rupes Nigra), or to Polaris, the pole star.[13] The idea that Earth itself acts as essentially a giant magnet was first proposed in 1600, by the English physician and natural philosopher William Gilbert. He was also the first to define the north magnetic pole as the point where Earth's magnetic field points vertically downwards. This is the current definition, though it would be a few hundred years before the nature of Earth's magnetic field was understood with modern accuracy and precision.[13]

Expeditions and measurements

editFirst observations

editThe first group to reach the north magnetic pole was led by James Clark Ross, who found it at Cape Adelaide on the Boothia Peninsula on June 1, 1831, while serving on the second arctic expedition of his uncle, Sir John Ross. Roald Amundsen found the north magnetic pole in a slightly different location in 1903. The third observation was by Canadian government scientists Paul Serson and Jack Clark, of the Dominion Astrophysical Observatory, who found the pole at Allen Lake on Prince of Wales Island in 1947.[14]

Project Polaris

editAt the start of the Cold War, the United States Department of War recognized a need for a comprehensive survey of the North American Arctic and asked the United States Army to undertake the task. An assignment was made in 1946 for the Army Air Forces' recently formed Strategic Air Command to explore the entire Arctic Ocean area. The exploration was conducted by the 46th (later re-designated the 72nd) Photo Reconnaissance Squadron and reported on as a classified Top Secret mission named Project Nanook. This project in turn was divided into many separate, but identically classified, projects, one of which was Project Polaris, which was a radar, photographic (trimetrogon, or three-angle, cameras) and visual study of the entire Canadian Archipelago. A Canadian officer observer was assigned to accompany each flight.

Frank O. Klein, the director of the project, noticed that the fluxgate compass did not behave as erratically as expected—it oscillated no more than 1 to 2 degrees over much of the region—and began to study northern terrestrial magnetism.[15][16] With the cooperation of many of his squadron teammates in obtaining many hundreds of statistical readings, startling results were revealed: The center of the north magnetic dip pole was on Prince of Wales Island some 400 km (250 mi) NNW of the positions determined by Amundsen and Ross, and the dip pole was not a point but occupied an elliptical region with foci about 400 km (250 mi) apart on Boothia Peninsula and Bathurst Island. Klein called the two foci local poles, for their importance to navigation in emergencies when using a "homing" procedure.[clarification needed] About three months after Klein's findings were officially reported, a Canadian ground expedition was sent into the Archipelago to locate the position of the magnetic pole. R. Glenn Madill, Chief of Terrestrial Magnetism, Department of Mines and Resources, Canada, wrote to Lt. Klein on 21 July 1948:

… we agree on one point and that is the presence of what we can call the main magnetic pole on northwestern Prince of Wales Island. I have accepted as a purely preliminary value the position latitude 73°N and longitude 100°W. Your value of 73°15'N and 99°45’W is in excellent agreement, and I suggest that you use your value by all means.

— R. Glenn Madill[15]

(The positions were less than 30 km (20 mi) apart.)

Modern (post-1996)

editThe Canadian government has made several measurements since, which show that the north magnetic pole is moving continually northwestward. In 2001, an expedition located the pole at 81°18′N 110°48′W / 81.300°N 110.800°W.

In 2007, the latest survey found the pole at 83°57′00″N 120°43′12″W / 83.95000°N 120.72000°W.[17] During the 20th century it moved 1,100 km (680 mi), and since 1970 its rate of motion has accelerated from 9 to 52 km (5.6 to 32.3 mi) per year (2001–2007 average; see also polar drift). Members of the 2007 expedition to locate the magnetic north pole wrote that such expeditions have become logistically difficult, as the pole moves farther away from inhabited locations. They expect that in the future, the magnetic pole position will be obtained from satellite data instead of ground surveys.[17]

This general movement is in addition to a daily or diurnal variation in which the north magnetic pole describes a rough ellipse, with a maximum deviation of 80 km (50 mi) from its mean position.[18] This effect is due to disturbances of the geomagnetic field by charged particles from the Sun.

As of early 2019, the magnetic north pole is moving from Canada towards Siberia at a rate of approximately 55 km (34 mi) per year.[19]

The NOAA gives the 2024 location of the magnetic north pole as 86 degrees North, 142 degrees East. By 2025, it will have drifted to 138 degrees East (same latitude).[20]

Exploration

editThe first team of novices to reach the magnetic north pole did so in 1996, led by David Hempleman-Adams. It included the first British woman Sue Stockdale and first Swedish woman to reach the Pole.[21][22][23] The team also successfully tracked the location of the Magnetic North Pole on behalf of the University of Ottawa, and certified its location by magnetometer and theodolite at 78°35′42″N 104°11′54″W / 78.59500°N 104.19833°W.[24][25]

The Polar Race was a biannual competition that ran from 2003 until 2011. It took place between the community of Resolute, on the shores of Resolute Bay, Nunavut, in northern Canada and the 1996 location of the north magnetic pole at 78°35′42″N 104°11′54″W / 78.59500°N 104.19833°W, also in northern Canada.

On 25 July 2007, the Top Gear: Polar Special was broadcast on BBC Two in the United Kingdom, in which Jeremy Clarkson, James May, and their support and camera team claimed to be the first people in history to reach the 1996 location of the north magnetic pole in northern Canada by car.[26][better source needed] Note that they did not reach the actual north magnetic pole, which at the time (2007) had moved several hundred kilometers further north from the 1996 position.[10][failed verification]

Magnetic north and magnetic declination

editHistorically, the magnetic compass was an important tool for navigation. While it has been widely replaced by Global Positioning Systems, many airplanes and ships still carry them, as do casual boaters and hikers.[27]

The direction in which a compass needle points is known as magnetic north. In general, this is not exactly the direction of the north magnetic pole (or of any other consistent location). Instead, the compass aligns itself to the local geomagnetic field, which varies in a complex manner over Earth's surface, as well as over time. The local angular difference between magnetic north and true north is called the magnetic declination. Most map coordinate systems are based on true north, and magnetic declination is often shown on map legends so that the direction of true north can be determined from north as indicated by a compass.[28]

In North America the line of zero declination (the agonic line) runs from the north magnetic pole down through Lake Superior and southward into the Gulf of Mexico (see figure). Along this line, true north is the same as magnetic north. West of the agonic line a compass will give a reading that is east of true north and by convention the magnetic declination is positive. Conversely, east of the agonic line a compass will point west of true north and the declination is negative.[29]

North geomagnetic pole

editAs a first-order approximation, Earth's magnetic field can be modeled as a simple dipole (like a bar magnet), tilted about 10° with respect to Earth's rotation axis (which defines the geographic north and geographic south poles) and centered at Earth's center. The north and south geomagnetic poles are the antipodal points where the axis of this theoretical dipole intersects Earth's surface. If Earth's magnetic field were a perfect dipole then the field lines would be vertical at the geomagnetic poles, and they would coincide with the magnetic poles. However, the approximation is imperfect, and so the magnetic and geomagnetic poles lie some distance apart.[30]

Like the north magnetic pole, the north geomagnetic pole attracts the north pole of a bar magnet and so is in a physical sense actually a magnetic south pole. It is the center of the region of the magnetosphere in which the Aurora Borealis can be seen. As of 2015 it was located at approximately 80°22′12″N 72°37′12″W / 80.37000°N 72.62000°W, over Ellesmere Island, Canada[30] but it is now drifting away from North America and toward Siberia.

Geomagnetic reversal

editOver the life of Earth, the orientation of Earth's magnetic field has reversed many times, with magnetic north becoming magnetic south and vice versa – an event known as a geomagnetic reversal. Evidence of geomagnetic reversals can be seen at mid-ocean ridges where tectonic plates move apart and the seabed is filled in with magma. As the magma seeps out of the mantle, cools, and solidifies into igneous rock, it is imprinted with a record of the direction of the magnetic field at the time that the magma cooled.[31]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Magnetic North, Geomagnetic and Magnetic Poles". wdc.kugi.kyoto-u.ac.jp. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ Livermore, Philip W.; Finlay, Christopher C.; Bayliff, Matthew (2020). "Recent north magnetic pole acceleration towards Siberia caused by flux lobe elongation". Nature Geoscience. 13 (5): 387–391. arXiv:2010.11033. Bibcode:2020NatGe..13..387L. doi:10.1038/s41561-020-0570-9. S2CID 218513160. Archived from the original on 14 June 2020. Alt URL

- ^ Merrill, Ronald T.; McElhinny, Michael W.; McFadden, Phillip L. (1996). "Chapter 8". The magnetic field of the earth: paleomagnetism, the core, and the deep mantle. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-491246-5.

- ^ Wei-Haas, Maya (4 February 2019). "Magnetic north just changed. Here's what that means". Science & Innovation. National Geographic. Archived from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ a b World Data Center for Geomagnetism, Kyoto. "Magnetic North, Geomagnetic and Magnetic Poles". Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ North Magnetic Pole Moving East Due to Core Flux, National Geographic, December 24, 2009

- ^ Petrovich Dubrov, Aleksandr (2013-11-11). The Geomagnetic Field and Life. Springer US. p. 12. ISBN 9781475716108.

- ^ NP.xy

- ^ "The Magnetic North Pole". Ocean bottom magnetology laboratory. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Archived from the original on 2013-08-19. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- ^ a b Nair, Manoj C. "Wandering of the Geomagnetic Poles | NCEI". ngdc.noaa.gov. Retrieved 2019-12-19.

- ^ Serway, Raymond A.; Chris Vuille (2006). Essentials of college physics. US: Cengage Learning. p. 493. ISBN 0-495-10619-4. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ Russell, Randy. "Earth's Magnetic Poles". Windows to the Universe. National Earth Science Teachers Association. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- ^ a b Early Concept of the North Magnetic Pole, Natural Resources Canada, retrieved June 2007

- ^ History of Expeditions to the North Magnetic Pole, Natural Resources Canada

- ^ a b White, Ken (1994). World in Peril: The Origin, Mission & Scientific Findings of the 46th / 72nd Reconnaissance Squadron (2nd revised ed.). K. W. White & Associates. ISBN 978-1883218102.

- ^ Wack, Fred John (1992). The Secret Explorers: Saga of the 46th/72nd Reconnaissance Squadrons. Seeger's Print.

- ^ a b L. R. Newitt, A. Chulliat, and J.-J. Orgeval, Location of the north magnetic pole in April 2007, Earth Planets Space, 61, 703–710, 2009

- ^ Geomagnetism – Daily Movement of the North Magnetic Pole, Natural Resources Canada

- ^ "Polar express: magnetic north pole moving 'pretty fast' towards Russia". Associated Press. 5 February 2019 – via theguardian.com.

- ^ "Wandering of the Geomagnetic Poles". NOAA. 10 March 2022.

- ^ Smith, Anna. "Scot of the Arctic; Sue conquers the North Pole". Daily Record. Archived from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ "North Pole party for 'Grand Slam' Briton". BBC News. 30 April 1998. Retrieved 12 June 2008.

- ^ Smith, Anna. "I have to do this not just for me … but for Scotland; Pole star: Sue's going where no Scotswoman has gone before". Daily Record. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ 1996 Certified Position of the Magnetic North Pole, Jock Wishart, Polar Race organiser

- ^ Wishart, Jock (13 July 2006). "Magnetic North Pole Location, 1996 in Ellef Ringnes Island, Canada". Virtualglobetrotting. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ "Polar Challenge". Top Gear. 25 July 2007. 0:22 minutes in. BBC Two. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ "Compass". National Geographic Society. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ "Magnetic declination". Natural Resources Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ USGS Education. "How To Use a Compass with a USGS Topographic Map". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Geomagnetism Frequently Asked Questions". National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 2018-04-28.

- ^ "Earth's Inconstant Magnetic Field – Science Mission Directorate". science.nasa.gov. 29 December 2003.

External links

edit- "Wandering of the geomagnetic poles". Geomagnetism. National Geophysical Data Center. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Geomagnetism". Natural Resources Canada. April 1, 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Map of pole's wandering

- "North Magnetic Pole could be leaving Canada". CNN.com. 20 March 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- "Magnetic pole drifting fast". BBC News. 12 December 2005. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- Nemiroff, R.; Bonnell, J., eds. (25 November 2002). "The Earth's magnetic field". Astronomy Picture of the Day. NASA. Retrieved 2012-04-19.