Magical Mystery Tour is a record by the English rock band the Beatles that was released as a double EP in the United Kingdom and an LP in the United States. It includes the soundtrack to the 1967 television film of the same name. The EP was issued in the UK on 8 December 1967 on the Parlophone label, while the Capitol Records LP release in the US and Canada occurred on 27 November and features an additional five songs that were originally released as singles that year. In 1976, Parlophone released the eleven-track LP in the UK.

| Magical Mystery Tour | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

UK release | ||||

| EP and soundtrack by | ||||

| Released | 27 November 1967 (US LP) 8 December 1967 (UK EP) | |||

| Recorded |

| |||

| Studio | EMI and Chappell, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | ||||

| Producer | George Martin | |||

| The Beatles EPs chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Alternative cover | ||||

US release | ||||

| The Beatles North American chronology | ||||

| ||||

When recording their new songs, the Beatles continued the studio experimentation that had typified Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967) and the psychedelic sound they had pursued since Revolver (1966). The project was initiated by Paul McCartney in April 1967, but after the band recorded the song "Magical Mystery Tour", it lay dormant until the death of their manager, Brian Epstein, in late August. Recording then took place alongside filming and editing, and as the Beatles furthered their public association with Transcendental Meditation under teacher Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

The sessions have been characterised by some biographers as aimless and unfocused, with the band members overly indulging in sound experimentation and exerting greater control over production. McCartney contributed three of the soundtrack songs, including the widely covered "The Fool on the Hill", while John Lennon and George Harrison contributed "I Am the Walrus" and "Blue Jay Way", respectively. The sessions also produced "Hello, Goodbye", issued as a single accompanying the soundtrack record, and items of incidental music for the film, including "Flying". Further to the Beatles' desire to experiment with record formats and packaging, the EP and LP included a 24-page booklet containing song lyrics, colour photos from film production, and colour story illustrations by cartoonist Bob Gibson.

Despite the mixed reception of the Magical Mystery Tour film, the soundtrack was a critical and commercial success. In the UK, it topped the EPs chart compiled by Record Retailer and peaked at number 2 on the magazine's singles chart (later the UK Singles Chart) behind "Hello, Goodbye". The album topped Billboard's Top LPs listings for eight weeks and was nominated for the Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1969. With the international standardisation of the Beatles' catalogue in 1987, Magical Mystery Tour became the only Capitol-generated LP to supersede the band's intended format and form part of their core catalogue.

Background

editAfter the Beatles completed Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band in April 1967, Paul McCartney wanted to create a film that captured a psychedelic theme similar to that represented by author and LSD proponent Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters on the US West Coast.[5][6] Titled Magical Mystery Tour, it would combine Kesey's idea of a psychedelic bus ride with McCartney's memories of Liverpudlians holidaying on coach tours.[7] The film was to be unscripted: various "ordinary" people were to travel on a coach and have unspecified "magical" adventures.[8] The Beatles began recording music for the soundtrack in late April, but the film idea then lay dormant. Instead, the band continued recording songs for the United Artists animated film Yellow Submarine and, in the case of "All You Need Is Love", for their appearance on the Our World satellite broadcast on 25 June,[9] before travelling over the summer months and focusing on launching their company Apple.[10]

In late August, while the Beatles were attending a Transcendental Meditation seminar held by Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Wales, their manager Brian Epstein died of a prescription drug overdose.[9] During a band meeting on 1 September, McCartney suggested they proceed with Magical Mystery Tour,[11] which Epstein had given his approval to earlier in the year.[12] McCartney was keen to ensure the group had a point of focus after the loss of their manager.[13][14] His view was at odds with his bandmates' wishes, with George Harrison especially eager to pursue their introduction to meditation.[15] According to publicist Tony Barrow, McCartney envisaged Magical Mystery Tour as "open[ing] doors for him" personally and as a new career phase for the band in which he would be the "executive producer" of their films.[16][nb 1] John Lennon later complained that the project was typical of McCartney's "tendency" to want to work as soon as he had songs ready to record, yet he himself was unprepared and had to set about writing new material.[17]

Recording and production

editRecording history

editThe Beatles first recorded the film's title song, with sessions taking place at EMI Studios in London between 25 April and 3 May. An instrumental jam was recorded on 9 May for possible inclusion in the film, although it was never completed.[18] According to Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn, the Magical Mystery Tour sessions "began in earnest" on 5 September; filming started on 11 September, and the two activities became increasingly "intertwined" during October.[19] Most of the 16 September session was dedicated to taping a basic track for McCartney's "Your Mother Should Know", only for McCartney to then decide to return to the version he had previously discarded, from 22–23 August.[20] The latter sessions marked the Beatles' first in close to two months[21][22] and took place at a facility new to the band – Chappell Recording Studios in central London – since they were unable to book EMI at short notice.[19]

Many Beatles biographers characterise the group's post-Sgt. Pepper recording sessions of 1967 as aimless and undisciplined.[23] The Beatles' use of psychedelic drugs such as LSD was at its height during that summer[24] and, in author Ian MacDonald's view, this resulted in a lack of judgment in their recordings as the band embraced randomness and sonic experimentation.[23][nb 2] George Martin, the group's producer, chose to distance himself from their work at this time, saying that much of the Magical Mystery Tour recording was "disorganised chaos". Ken Scott, who became their senior recording engineer during the sessions, recalled, "the Beatles had taken over things so much that I was more their right-hand man than George Martin's".[26][nb 3]

Early, pre-overdub mixes of some of the film songs were prepared on 16 September,[28] before the Beatles performed the music sequences during a six-day shoot at RAF West Malling, a Royal Air Force base in Kent.[29] The recording sessions continued alongside editing of the film footage, which took place in an editing suite in Soho and was mostly overseen by McCartney.[30] The process led to a struggle between him and Lennon over the film's content.[31][nb 4] The Beatles also recorded "Hello, Goodbye" for release as a single accompanying the soundtrack record.[35] That his film song "I Am the Walrus" was relegated to the B-side of the single, in favour of McCartney's pop-oriented "Hello, Goodbye", was another source of rancour for Lennon.[36][37] He later recalled, "I began to submerge."[38]

During this time, the band's commitment to the Maharishi's teachings remained strong.[39] Barrow later wrote that Lennon, Harrison and Ringo Starr were "itching" to travel to India and study with their teacher, but they agreed to postpone the trip and complete the film's soundtrack and editing.[40] Harrison and Lennon promoted Transcendental Meditation with two appearances on David Frost's TV show The Frost Programme, and Harrison and Starr visited the Maharishi in Copenhagen. All four band members attended the 17 October memorial service for Epstein, held at the New London Synagogue on Abbey Road, close to EMI Studios, and the 18 October world premiere of How I Won the War, a film in which Lennon had a starring role.[41] Recording for Magical Mystery Tour was completed on 7 November.[42] That day, the title song was given a new barker-style introduction by McCartney (replacing Lennon's effort, which was nevertheless retained in the version used in the film)[43] and an overdub of traffic sounds.[42]

Three pieces of incidental music were recorded but omitted from the soundtrack record.[44] In the case of "Shirley's Wild Accordion", the scene was cut from the film.[45] Featuring an accordion score by arranger Mike Leander, it was performed by Shirley Evans with percussion contributions from Starr and McCartney,[35] and recorded at De Lane Lea Studios in October.[46] "Jessie's Dream" was taped privately by the Beatles and copyrighted to McCartney–Starkey–Harrison–Lennon,[35] while the third item was a brief Mellotron piece used to orchestrate the line "The magic is beginning to work" in the film.[44][nb 5]

Production techniques and sounds

editThey half knew what they wanted and half didn't know, not until they'd tried everything. The only specific thought they seemed to have in their mind was to be different.[49]

– EMI engineer Ken Scott on the band's approach to recording Magical Mystery Tour

In their new songs, the Beatles continued the studio experimentation that had typified Sgt. Pepper[50] and the psychedelic sound they had introduced in 1966 with Revolver.[51] Author Mark Hertsgaard highlights "I Am the Walrus" as the fulfilment of the band's "guiding principle" during the sessions – namely to experiment and be "different".[49] To satisfy Lennon's request that his voice should sound like "it came from the moon", the engineers gave him a low-quality microphone to sing into and saturated the signal from the preamp microphone.[52] In addition to the song's string and horn arrangement, Martin wrote a score for the sixteen backing vocalists (the Mike Sammes Singers), in which their laughter, exaggerated vocalising and other noises evoked the LSD-inspired mood that Lennon sought for the piece.[53] The orchestral arrangement and the vocal score were recorded on a separate four-track tape, which Martin and Scott then manually synchronised with the tape containing the band's performance.[52] The track was completed with Lennon overdubbing live radio signals found at random, finally settling on a BBC Third Programme broadcast of Shakespeare's The Tragedy of King Lear.[35]

According to musicologist Thomas MacFarlane, Magical Mystery Tour shows the Beatles once more "focusing on colour and texture as important compositional elements" and exploring the "aesthetic possibilities" of studio technology.[54] "Blue Jay Way" features extensive use of three studio techniques employed by the Beatles over 1966–67:[55] flanging, an audio delay effect;[56] sound-signal rotation via a Leslie speaker;[57] and (in the stereo mix only) reversed tapes.[58] In the case of the latter technique, a recording of the completed track was played backwards and faded in at key points during the performance,[59] creating an effect whereby the backing vocals appear to answer each line of Harrison's lead vocal in the verses.[58] Due to the limits of multitracking, the process of feeding in reversed sounds was carried out live during the final mixing session.[59][nb 6] A tape loop of decelerated guitar sounds was used on "The Fool on the Hill"[61] to create a swooshing bird-like effect towards the end of that song.[62] Lennon and Starr prepared seven minutes' worth of tape loops as a coda to "Flying", but this was discarded,[63][64] leaving the track to end with a 30-second burst of Mellotron sounds.[57]

Although he recognises Sgt. Pepper as the highpoint of the Beatles' application of sound "colorisation", musicologist Walter Everett says that the band introduced some effective "new touches" during this period. He highlights the slow guitar tremolo on "Flying", the combination of female and male vocal chorus, cello glissandi and found sounds on "I Am the Walrus", and the interplay between the lead vocal and violas on "Hello, Goodbye".[65] In MacFarlane's description, the songs reflect the Beatles' growing interest in stereo mixes, as "remarkable sonic qualities" are revealed in the placement of sounds across the stereo image, making for a more active listening experience.[66]

Songs

editSoundtrack

editMagical Mystery Tour included six tracks, a number that posed a challenge for the Beatles and their UK record company, EMI, as there were too few for an LP album but too many for an EP.[67] One idea considered was to issue an EP that played at 33⅓ rpm, but this would have caused a loss of audio fidelity that was deemed unacceptable. The solution chosen was to issue the music in the innovative format of a double EP.[68] It was the first example of a double EP in Britain.[68][69]

According to music journalist Rob Chapman, each of the new tracks "represents a distinct facet of the group's psychedelic vision". He gives these as, in order of the EP's sequencing: celebration, nostalgia, absurdity, innocence, bliss and dislocation.[70] Musicologist Russell Reising says that the songs variously further the Beatles' exploration of the thematic links between a psychedelic trip and travelling, and address the relationship between travel and time.[71] Ethnomusicologist David Reck comments that despite the Beatles' association with Eastern culture at the time, through their championing of the Maharishi, just two of the EP's songs directly reflect this interest.[72]

"Magical Mystery Tour"

edit"Magical Mystery Tour" was written as the main theme song shortly after McCartney conceived the idea for the film.[73] In Hunter Davies' contemporary account of the 25 April session, McCartney arrived with the chord structure but only the opening refrain ("Roll up / Roll up for the mystery tour"), necessitating a brainstorming discussion the following day to complete the lyrics.[74] Like "Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band", the song serves to welcome the audience to the event and uses a trumpet fanfare.[75][76]

"Your Mother Should Know"

edit"Your Mother Should Know" is a song in the music hall style[58] similar to McCartney's "When I'm Sixty-Four" from Sgt. Pepper.[77] Its lyrical premise centres on the history of hit songs across generations.[78] He originally offered it for the Our World broadcast, but the Beatles favoured Lennon's "All You Need Is Love" for its social significance.[79] McCartney later said he wrote the song as a production number for Magical Mystery Tour,[80] where it provides the film's closing, Busby Berkeley–style dance sequence.[81] In author Doyle Greene's view, the lyrics advocate generational understanding in the manner of "She's Leaving Home" but, unlike in the latter song, to the point of "maternal authority and youth compliance", and contrast sharply with the confrontational message of the EP's next track.[82][nb 7]

"I Am the Walrus"

edit"I Am the Walrus" was Lennon's main contribution to the film and was primarily inspired by both his experiences with LSD and Lewis Carroll's poem "The Walrus and the Carpenter"[83] from Through the Looking Glass.[84] The impetus came from a fan letter Lennon received from a student at his former high school, Quarry Bank, in which he learned that an English literature teacher there was interpreting the Beatles' lyrics in a scholarly fashion. Amused by this, Lennon set out to write a lyric that would confound analysis from scholars and music journalists.[85] In addition to drawing on Carroll's imagery and Shakespeare's King Lear, he reworked a nursery rhyme from his school days,[86] and referenced Edgar Allan Poe[87] and (in the vocalised "googoogajoob"s) James Joyce.[62] Author Jonathan Gould describes "I Am the Walrus" as "the most overtly 'literary' song the Beatles would ever record",[88] while MacDonald deems it "[Lennon's] ultimate anti-institutional rant – a damn-you-England tirade that blasts education, art, culture, law, order, class, religion, and even sense itself".[87]

"The Fool on the Hill"

editMcCartney wrote the melody for "The Fool on the Hill" during the Sgt. Pepper sessions but the lyrics remained incomplete until September.[89] The song is about a solitary figure who is not understood by others, but is actually wise.[90] In Everett's interpretation, the fool's innocence leaves him adrift from and unwilling to engage with a judgmental society.[91] McCartney said the idea was inspired by the Dutch design collective the Fool, who derived their name from the tarot card of the same name, and possibly by the Maharishi.[92][nb 8] A piano ballad, its musical arrangement includes flutes and bass harmonicas,[94] and a recorder solo played by McCartney.[62] The song's sequence in Magical Mystery Tour involved a dedicated film shoot, featuring McCartney on a hillside overlooking Nice, in the South of France,[95] which added considerably to the film's production costs.[96]

"Flying"

edit"Flying" is an instrumental and the first Beatles track to be credited to all four members of the band. It was titled "Aerial Tour Instrumental" until late in the sessions[97] and appears in the film over footage of clouds[98] and outtakes from Stanley Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove.[99][nb 9] The track's musical structure is similar to a 12-bar blues[44] and set to what music historian Richie Unterberger terms a "rock–soul rhythm".[101] It consists of three rounds of the 12-bar pattern, led first by guitars, then Mellotron and organ, and finally a chanted vocal chorus.[44]

"Blue Jay Way"

edit"Blue Jay Way" was named after a street in the Hollywood Hills of Los Angeles where Harrison stayed in August 1967. The lyrics document his wait for music publicist Derek Taylor to find his way to Blue Jay Way through the fog-ridden hills, while Harrison struggled to stay awake after the flight from London to Los Angeles.[78] MacDonald describes the song as Harrison's "farewell to psychedelia", since his subsequent visit to Haight-Ashbury led to him seeking an alternative to hallucinogenic drugs and opened the way to the Beatles' embrace of Transcendental Meditation.[105] The composition marked a rare example of the Lydian mode being used in pop music[106] and, in Reck's view, incorporates scalar elements from the Carnatic raga Ranjani.[107][nb 10]

Singles

editBecause EPs were not popular in the US at the time, Capitol Records released the soundtrack as an LP by adding tracks from that year's non-album singles.[67][108] The first side contained the film soundtrack songs, although in a different order from the EP.[109] Side two contained both sides of the band's two singles released up to this point in 1967, along with "Hello, Goodbye", which was issued as a single backed by "I Am the Walrus". Three of the previously released tracks – "Penny Lane", "Baby, You're a Rich Man" and "All You Need Is Love" – were presented in duophonic (or "processed") stereo sound on Capitol's stereo version of the LP.[67]

The Beatles were displeased about this reconfiguration, since they believed that tracks released on a single should not then appear on a new album.[67][110] Lennon referred to the LP at a May 1968 press conference to promote Apple Corps in the US,[111] saying: "It's not an album, you see. It turned into an album over here, but it was just [meant to be] the music from the film."[112]

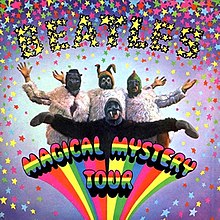

Artwork and packaging

editAs part of the unusual format, the Beatles decided to package the two EPs in a gatefold sleeve with a 24-page booklet.[68][114] The record's cover featured a photo of the Beatles in animal costumes, taken during the shoot for "I Am the Walrus", and marked the first time that the band members' faces were not visible on one of their EP or LP releases.[115] The booklet contained song lyrics, photographer John Kelly's colour stills from the filming,[116] and colour story illustrations in the comic strip style[68] by Beatles Book cartoonist Bob Gibson.[67] It was compiled by Barrow, with input from McCartney.[117][nb 11] Of the double-EP package, film studies academic Bob Neaverson later commented: "While it certainly solved the song quota problem, one suspects that it was also partly born of the Beatles' pioneering desire to experiment with conventional formats and packaging."[119] In line with the band's wishes, the packaging reinforced the idea that the release was a film soundtrack rather than a follow-up to Sgt. Pepper, which was still receiving critical plaudits and enjoying commercial success in late 1967.[120]

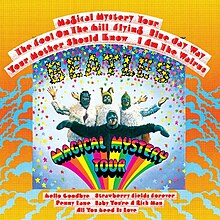

When preparing the US release, Capitol enlarged the photos and illustrations to LP size inside a gatefold album sleeve.[114] The cover design was done by John Van Hamersveld,[121] the head of Capitol's art department, working from the artwork sent from EMI in London.[122] He recalled that Capitol's vice-president of distribution was concerned about how to market a record where the Beatles' faces were hidden behind their costumes, since cover portraits had been key to the success of the group's US LPs. Van Hamersveld therefore augmented the "underground graphic" cover image with a design concept that highlighted the songs.[123]

In Gould's description, the LP cover "had the garish symmetry of a movie poster" through the combination of the Beatles' animal costumes, the "rainbow" film logo, and the song titles rendered in art-deco lettering "amid a border of op-art clouds".[124][nb 12] The artwork was later cited by proponents of the Paul is dead theory as evidence of McCartney's alleged demise in November 1966.[126] Clues included the appearance of a black walrus (Lennon in costume) on the front cover, which was thought to signify death in some areas of Scandinavia; McCartney wearing a black carnation in an image from the "Your Mother Should Know" film sequence; and, on another page from the booklet, McCartney seated behind a sign reading "I WaS".[127]

Release

editIn advance of the EP's release, Lennon promoted the soundtrack in an interview on the BBC Radio 1 show Where It's At.[128][129] Lennon discussed the studio effects used on the new songs, including "I Am the Walrus",[129] which received its only contemporary airing on BBC radio when disc jockey Kenny Everett played it as part of the interview broadcast on 25 November 1967.[128] According to author John Winn, because the lyrics included the word "knickers", the song "remained unofficially prohibited from BBC playlists for the time being".[130] "I Am the Walrus" was also banned from American airwaves.[128]

Magical Mystery Tour was issued in the UK on 8 December, the day after the opening of their Apple Boutique in central London, and just over two weeks before the film was broadcast by BBC Television.[131] It retailed at the sub-£1 price of 19s 6d (equivalent to £22 today).[67] It was their thirteenth British EP and only their second, after 1964's Long Tall Sally, to consist of entirely new recordings.[132] With the broadcast rights for North America assigned to NBC, the Capitol album was scheduled for a mid-December release.[133] The company instead issued the album on 27 November. In Britain only, the film was then screened on Boxing Day to an audience estimated at 15 million.[8] It was savaged by reviewers,[134][135] giving the Beatles their first public and critical failure.[136][137] As a result, the American broadcaster withdrew its bid for the local rights, and the film was not shown there at the time.[8][nb 13]

Any resentment or hostility that the watching audience might have felt towards the Boxing Day broadcast of Magical Mystery Tour was more than amply counterbalanced by the fact that for three weeks over the Christmas and new year period the "Hello, Goodbye" single and the Magical Mystery Tour EP were numbers one and two in the UK singles chart. You heard them everywhere and all the time, resplendent in tandem.[139]

– Music journalist Rob Chapman

In its first three weeks on sale in the US, Magical Mystery Tour set a record for the highest initial sales of any Capitol LP.[140] It was number 1 on Billboard's Top LPs listings for eight weeks at the start of 1968 and remained in the top 200 until 8 February 1969.[141][nb 14] It was nominated for a Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1969.[144]

In Britain, the EP peaked at number 2 on the national singles chart,[145] behind "Hello, Goodbye",[146][147] and became the Beatles' ninth release to top the national EPs chart compiled by Record Retailer.[148] In the UK singles listings compiled by Melody Maker magazine, it replaced "Hello, Goodbye" at number 1 for a week.[149] The EP sold over 500,000 copies there.[138] Walter Everett highlights its UK chart performance as a significant achievement, given that the EP's retail price far exceeded that of the singles with which it was competing at the time.[138] As an American import, the Capitol album release peaked on the Record Retailer LPs chart at number 31 in January 1968.[150] In the US, the album sold 1,936,063 copies by 31 December 1967 and 2,373,987 copies by the end of the decade.[151]

According to music historian Clinton Heylin, the release of Magical Mystery Tour and of the Rolling Stones' Their Satanic Majesties Request, which was the Stones' answer to Sgt. Pepper, inadvertently brought an end to psychedelic pop.[152] Music journalist John Harris cites the critical maligning of the film as the excuse the British authorities were looking for to begin targeting the Beatles, despite the band's status as MBE holders, for their wayward influence on youth.[153] Within the Beatles, McCartney's role as the group's de facto leader, a role he had assumed with Lennon's withdrawal before Sgt. Pepper,[154] was destabilised as individual creative agendas were increasingly pursued over 1968.[155]

In 1968, jazz musician Bud Shank released the album Magical Mystery, which included five of the EP's tracks and "Hello, Goodbye".[citation needed] "The Fool on the Hill" was highly popular among other artists, particularly cabaret performers,[156] and became one of the most covered Lennon–McCartney compositions.[102]

Critical reception

editContemporary reviews

editReviewing the EP a month before the film's screening, Nick Logan of the NME enthused that the Beatles were "at it again, stretching pop music to its limits". He continued: "The four musician-magicians take us by the hand and lead us happily tripping through the clouds, past Lucy in the sky with diamonds and the fool on the hill, into the sun-speckled glades along Blue Jay Way and into the world of Alice in Wonderland ... This is The Beatles out there in front and the rest of us in their wake."[157][158] Bob Dawbarn of Melody Maker described the EP as "six tracks which no other pop group in the world could begin to approach for originality combined with the popular touch".[116] In Record Mirror, Norman Jopling wrote that, whereas on Sgt. Pepper "the effects were chiefly sound and only the album cover was visual", on Magical Mystery Tour "the visual side ... has dominated the music", such that "Everything from fantasy, children's comics, acid (psychedelic) humour is included on the record and in the booklet."[159]

Among reviews of the American LP, Mike Jahn of Saturday Review hailed Magical Mystery Tour as the Beatles' best work yet, superior to Sgt. Pepper in emotion and depth, and "distinguished by its description of the Beatles' acquired Hindu philosophy and its subsequent application to everyday life".[160] Hit Parader said that "the beautiful Beatles do it again, widening the gap between them and 80 scillion other groups." Remarking on how the Beatles and their producer "present a supreme example of team work", the reviewer compared the album with Their Satanic Majesties Request and opined that "I Am the Walrus" and "Blue Jay Way" alone "accomplish what the Stones attempted".[161] Rolling Stone was launched in October 1967 with a cover photo of Lennon from How I Won the War;[162] in its fourth issue, the magazine's review of Magical Mystery Tour consisted of a single-sentence quote from him: "There are only about 100 people in the world who understand our music."[163][nb 15]

Having been one of the few critics to review Sgt. Pepper unfavourably,[165] Richard Goldstein of The New York Times rued that the new songs furthered the gap between true rock values and studio effects, and that the band's "fascination with motif" was equally reflected in the elaborate packaging. Goldstein concluded: "Does it sound like heresy to say that the Beatles write material which is literate, courageous, genuine, but spotty? It shouldn't. They are inspired posers, but we must keep our heads on their music, not their incarnations."[166] Rex Reed of HiFi/Stereo Review wrote a scathing critique in which he derided the group's "farcical, stagnant, helpless bellowing" and "confused musical ideas". Reed said that exchanging drugs for meditation as their subject matter had left the Beatles "totally divorced from reality", and he especially ridiculed "I Am the Walrus" on an LP he deemed a "platter of phony, pretentious, overcooked tripe".[167] In his May 1968 column in Esquire, Robert Christgau considered three of the new songs to be "disappointing", among which "The Fool on the Hill" "may be the worst song the Beatles have ever recorded". Christgau still found it a valid album, "for all the singles, which are good music, after all; for the tender camp of 'Your Mother Should Know'; and especially for Harrison's hypnotic 'Blue Jay Way,' an adaptation of Oriental modes in which everything works, lyrics included".[168]

Retrospective assessments

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [169] |

| Blender | [170] |

| Consequence of Sound | A+[171] |

| The Daily Telegraph | [172] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | [173] |

| MusicHound Rock | 3/5[174] |

| Paste | 94/100[175] |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[176] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [177] |

| Sputnikmusic | 4.5/5[178] |

In his review for Blender, Paul Du Noyer writes: "They lost the plot with their dopey TV film, but 1967 was still their zenith as songwriters. For once, the U.S. release went better than the British original ... The result was simply the best set of Beatles tunes so far on a single disc."[170] AllMusic critic Richie Unterberger opines that the psychedelia is "even spacier in parts" than on Sgt. Pepper, but "there's no vague overall conceptual/thematic unity to the material, which has made Magical Mystery Tour suffer slightly in comparison. Still, the music is mostly great."[169] Scott Plagenhoef of Pitchfork describes the EP-exclusive tracks as "low key marvels".[176] He says that while the album lacks a progressive quality from the band's previous work, it "is quietly one of the most rewarding listens in the Beatles' career", and the mixed nature of the collection "matters little when the music itself is so incredible".[121]

Writing in The Rolling Stone Album Guide, Rob Sheffield says that the album is "a lot goopier than Sgt. Pepper, though lifted by the cheerful 'All You Need Is Love' and the ghostly 'Strawberry Fields Forever.' Her Majesty the Queen had the best comment: 'The Beatles are turning awfully funny, aren't they?'"[179] Neil McCormick of The Daily Telegraph writes that the combination of soundtrack and singles means the album lacks cohesion, but he still finds it an "intriguing psychedelic companion piece" to Sgt. Pepper and highlights "I Am the Walrus" as a "mad, surrealist epic ... in which Lennon takes the concept of lyrical and musical nonsense and just explodes it all over the speakers".[172] Reviewing for Mojo in 2002, Charles Shaar Murray said Magical Mystery Tour was the Beatles album he turned to most often following Harrison's death the previous year and that it evokes an era "when society still seemed to be opening up rather than closing down".[180] Given its experimental qualities, he deemed it "the other half of the double-album that Sgt. Pepper should have been".[181] Writing for Paste, Mark Kemp views Magical Mystery Tour as a work of "symphonic sprawl" that marks the culmination of a five-year period in which the Beatles led pop music's expansion into world music, psychedelia, avant-pop and electronica, while bringing the genre a bohemian audience for the first time. He says that while the album resembles a Sgt. Pepper "Part 2", it "breathes easier and includes stronger songs" and benefits from the lack of a "forced concept".[175]

Among Beatles biographers, Jonathan Gould says the album's resequencing of the EP songs heightens the project's "Pepper redux" quality, with its opening title track recalling "Sgt. Pepper" and "I Am the Walrus" providing the "weighty end" in the manner of "A Day in the Life". He similarly views "The Fool on the Hill" as the "Fixing a Hole"–style "cool, contemplative ballad", just as Harrison provides "another droning epic" and McCartney offers "another archaic number" in "Your Mother Should Know", which he finds a "halfhearted attempt at satiric nostalgia".[182] Chris Ingham, writing in The Rough Guide to the Beatles, says that the soundtrack's reputation suffers from its association with the film's failure, yet while three of the tracks are rightly overlooked, "The Fool on the Hill", "Blue Jay Way" and "I Am the Walrus" remain "essential Beatlemusic".[183]

Magical Mystery Tour was ranked at number 138 in Paul Gambaccini's 1978 book Critic's Choice: Top 200 Albums, based on submissions from a panel of 47 critics and broadcasters.[184][185] In 2000, it was voted 334th in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums.[186] In his book The Ambient Century, Mark Prendergast describes it as "the most psychedelic album The Beatles ever released" and, along with Revolver, an "essential purchase".[187] He ranks the album at number 27 in his list of "Twentieth-century Ambience – the Essential 100 Recordings".[188] In 2007, the album was included in Robert Christgau and David Fricke's "40 Essential Albums of 1967" for Rolling Stone. Christgau wrote in an accompanying essay: "Because it begins with the lame theme to their worst movie and the sappy 'Fool on the Hill,' few realize that this serves up three worthy obscurities forthwith – bet Beck knows the sour-and-sweet instrumental 'Flying' by heart. Then it A/Bs three fabulous singles."[189]

Release history

editIn 1968 and 1971, true-stereo mixes were created for "Penny Lane", "Baby, You're a Rich Man" and "All You Need Is Love",[67] which allowed the first true-stereo version of the Magical Mystery Tour LP to be issued in West Germany in 1971.[190] In the face of continued public demand for the imported Capitol album, EMI officially released the Magical Mystery Tour LP in the UK in November 1976,[191] although it used the Capitol fake-stereo masters of the same three singles tracks.[67] In 1981, the soundtrack EP was reissued in both mono and stereo as part of Parlophone's 15-disc box set The Beatles EP Collection.[192][193]

When standardising the Beatles' releases for the worldwide compact disc release in 1987, EMI issued Magical Mystery Tour as a full-length album in true stereo.[103] It was the only example of an American reconfigured release being favoured over the EMI version.[194] The inclusion of the 1967 singles on CD with this album meant that the Magical Mystery Tour CD would be of comparable length to the band's CDs of its original albums, and that the additional five tracks originally featured on the American LP would not need to be included on Past Masters, a two-volume compilation designed to accompany the initial CD album releases and provide all non-album tracks (mostly singles) on CD format.[195]

The album (along with the Beatles' entire UK studio album catalogue) was remastered and reissued on CD in 2009. Acknowledging the album's conception and first release, the CD incorporates the original Capitol LP label design. The remastered stereo CD features a mini-documentary about the album. Initial copies of the album accidentally list the mini-documentary to be one made for Let It Be. The mono album was reissued as part of The Beatles in Mono CD and LP box sets in 2009 and 2014 respectively. The packaging includes the 24-page booklet from the original, reduced in size in the case of the CD. In 2012 the stereo album was reissued on vinyl, using the 2009 remasters and the US track lineup and including the 24-page booklet.[citation needed]

The 2012 remastered Magical Mystery Tour DVD entered the Billboard Top Music Video chart at number 1. The CD album climbed to number 1 on the Billboard Catalog Albums chart, number 2 on the Billboard Soundtrack albums chart, and re-entered at number 57 on the Billboard 200 albums chart for the week ending 27 October 2012.[196]

Track listing

editAll tracks are written by Lennon–McCartney, except "Blue Jay Way" by George Harrison, and "Flying"[197] by Harrison–Lennon–McCartney–Starkey.[198]

Double EP

edit| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Magical Mystery Tour" | McCartney with Lennon | 2:48 |

| 2. | "Your Mother Should Know" | McCartney | 2:33 |

| Total length: | 5:21 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "I Am the Walrus" | Lennon | 4:35 |

| Total length: | 4:35 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "The Fool on the Hill" | McCartney | 3:00 |

| 2. | "Flying" | Instrumental | 2:16 |

| Total length: | 5:16 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Blue Jay Way" | Harrison | 3:50 |

| Total length: | 3:50 (19:02) | ||

LP

edit| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Magical Mystery Tour" | McCartney with Lennon | 2:48 |

| 2. | "The Fool on the Hill" | McCartney | 2:59 |

| 3. | "Flying" | Instrumental | 2:16 |

| 4. | "Blue Jay Way" | Harrison | 3:54 |

| 5. | "Your Mother Should Know" | McCartney | 2:33 |

| 6. | "I Am the Walrus" | Lennon | 4:35 |

| Total length: | 19:05 | ||

| No. | Title | Lead vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Hello, Goodbye" | McCartney | 3:24 |

| 2. | "Strawberry Fields Forever" | Lennon | 4:05 |

| 3. | "Penny Lane" | McCartney | 3:00 |

| 4. | "Baby, You're a Rich Man" | Lennon | 3:07 |

| 5. | "All You Need Is Love" | Lennon | 3:57 |

| Total length: | 17:33 (36:35) | ||

Personnel

editAccording to Mark Lewisohn[199] and Ian MacDonald,[200] except where noted:

The Beatles

- John Lennon – lead, harmony and backing vocals; wordless vocals on "Flying"; rhythm and acoustic guitars; piano, Mellotron, Hammond organ, electric piano, clavioline, harpsichord; bass harmonica, Jew's harp, banjo, percussion

- Paul McCartney – lead, harmony and backing vocals; wordless vocals on "Flying"; bass, acoustic and lead guitars; piano, Mellotron, harmonium; recorder, penny whistle, percussion

- George Harrison – harmony and backing vocals; lead vocals on "Blue Jay Way"; wordless vocals on "Flying"; lead, rhythm, acoustic and slide guitars; Hammond organ, bass harmonica, swarmandal, violin, percussion

- Ringo Starr – drums and percussion; backing vocals on "Hello, Goodbye"; wordless vocals on "Flying"

Additional musicians and production

- "Magical Mystery Tour" – Mal Evans and Neil Aspinall on percussion; David Mason, Elgar Howarth, Roy Copestake and John Wilbraham on trumpets

- "I Am the Walrus" – Sidney Sax, Jack Rothstein, Ralph Elman, Andrew McGee, Jack Greene, Louis Stevens, John Jezzard and Jack Richards on violins; Lionel Ross, Eldon Fox, Brian Martin and Terry Weil on cellos; Neill Sanders, Tony Tunstall and Morris Miller on horns; Mike Sammes Singers (Peggie Allen, Wendy Horan, Pat Whitmore, Jill Utting, June Day, Sylvia King, Irene King, G. Mallen, Fred Lucas, Mike Redway, John O'Neill, F. Dachtler, Allan Grant, D. Griffiths, J. Smith and J. Fraser) on backing vocals

- "The Fool on the Hill" – Christoper Taylor, Richard Taylor and Jack Ellory on flute

- "Blue Jay Way" – unidentified session musician on cello[201]

- "Hello, Goodbye" – Ken Essex and Leo Birnbaum on violas

- "Strawberry Fields Forever" – Mal Evans on percussion; Tony Fisher, Greg Bowen, Derek Watkins and Stanley Roderick on trumpets; John Hall, Derek Simpson, Peter Halling and Norman Jones on cellos

- "Penny Lane" – George Martin on piano; Ray Swinfield, P. Goody, Manny Winters and Dennis Walton on flutes; Leon Calvert, Freddy Clayton, Bert Courtley and Duncan Campbell on trumpets; Dick Morgan and Mike Winfield on English horns; Frank Clarke on double bass; David Mason on piccolo trumpet

- "Baby, You're a Rich Man" – Eddie Kramer on vibraphone

- "All You Need Is Love" – George Martin on piano; Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Marianne Faithfull, Keith Moon, Eric Clapton, Pattie Boyd Harrison, Jane Asher, Mike McGear, Graham Nash, Gary Leeds, Hunter Davies and others on backing vocals; Sidney Sax, Patrick Halling, Eric Bowie and John Ronayne on violins; Lionel Ross and Jack Holmes on cellos; Rex Morris and Don Honeywill on tenor saxophones; David Mason and Stanley Woods on trumpets and flugelhorn; Evan Watkins and Henry Spain on trombones; Jack Emblow on accordion[202]

- Geoff Emerick, Ken Scott – audio engineering

Charts

editOriginal release

Certificationsedit

† BPI certification awarded only for sales since 1994.[237] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Barrow also said that McCartney was concerned that if the others travelled to India to study with the Maharishi, it would mean the end of the Beatles.[15]

- ^ According to MacDonald, the Beatles' "native sharpness" began to re-emerge in late August, after their two-month holiday, but "never fully returned after Sgt. Pepper".[25]

- ^ Martin said the band's "undisciplined, sometimes self-indulgent" method of working during Magical Mystery Tour was preceded by the "anarchy" they had introduced to the recording of the Sgt. Pepper track "Lovely Rita". Then, an entire session was dedicated to overdubbing backing vocals, sundry noises and a paper-and-comb "orchestra".[27]

- ^ Harrison began working on the soundtrack to the psychedelic film Wonderwall in November 1967.[32][33] According to director Joe Massot, Harrison accepted the commission because Magical Mystery Tour was "Paul's project" and he welcomed the opportunity to have a free hand in creating a film soundtrack.[34]

- ^ The film also included "She Loves You", played on a fairground organ; an orchestral version of "All My Loving"; and "Death Cab for Cutie", performed by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band.[47] In addition, the coda of "Hello, Goodbye" played over the end credits.[48]

- ^ Described by Lewisohn as "quite problematical",[42] the process was not repeated for the mono mix of "Blue Jay Way".[59] Lewisohn adds that, like Lennon's "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "I Am the Walrus", the song "makes fascinating listening for anyone interested in what could be achieved in a 1967 recording studio".[60]

- ^ Greene adds that the sense of old-fashioned compliance in "Your Mother Should Know" is lessened in the film sequence for the song. He cites the entrance of a group of female RAF cadets, amid a crowd of formally dressed ballroom dancers, as an example of the scene having "a satirical undercurrent and [addressing] the fissures of late 1960s politics".[81]

- ^ In the recollection of Alistair Taylor, a former assistant of Epstein, the song originated after he and McCartney were walking on Primrose Hill in north London and a man appeared before them but suddenly vanished. According to Taylor, he and McCartney later discussed the existence of God, which led McCartney to write "The Fool on the Hill".[93]

- ^ Recorded three days before shooting on Magical Mystery Tour began, "Aerial Tour Instrumental" was originally intended to accompany a scene in which the Beatles' psychedelic coach took flight with the aid of special effects.[100]

- ^ Alternatively, Everett considers "Blue Jay Way" to be related to the Carnatic raga Kosalam and to Multani, a Hindustani raga.[58]

- ^ The EP credits read, "Book Edited by Tony Barrow", while Neil Aspinall and Mal Evans were listed as "Editorial Consultants (for Apple)".[118]

- ^ Van Hamersveld recalled working on the cover alongside his psychedelic poster for the first Pinnacle Shrine rock exposition.[125]

- ^ The film had been scheduled for broadcast in the US over the Easter weekend.[138]

- ^ Due to the alleged clues in its artwork, the album returned to the Billboard chart in late 1969, at the height of the "Paul is dead" rumours.[126][142] Among several records that exploited this phenomenon,[126] a group calling themselves the Mystery Tour issued the single "The Ballad of Paul".[143]

- ^ Lennon made the remark following the December 1965 TV special The Music of Lennon & McCartney, in reference to other artists covering their songs.[164]

References

edit- ^ Wolk, Douglas (27 November 2017). "'Magical Mystery Tour': Inside Beatles' Psychedelic Album Odyssey". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 30 August 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Williams, Stereo (26 November 2017). "The Beatles' 'Magical Mystery Tour' at 50". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ J. Faulk, Barry (23 May 2016). British Rock Modernism, 1967-1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock. Taylor & Francis. p. 75. ISBN 9781317171522. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Gallucci, Michael (January 2013). "45 Years Ago: The Beatles' 'Magical Mystery Tour' Tops the Charts". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, p. 254.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 439.

- ^ Stark 2005, p. 218.

- ^ a b c Schaffner 1978, p. 90.

- ^ a b Miles 2001, pp. 276–77.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 354.

- ^ Brown & Gaines 2002, pp. 252–53.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 263.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 230.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 439–40.

- ^ a b Stark 2005, p. 217.

- ^ Greene 2016, p. 38.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 263, 285.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 274.

- ^ a b Lewisohn 2005, p. 122.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 122, 126.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 117.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 179.

- ^ a b Harris, John (March 2007). "The Day the World Turned Day-Glo!". Mojo. p. 89.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 129.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 263–64.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 173.

- ^ Heylin 2007, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 126.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 79, 117.

- ^ Black 2002, pp. 137–38.

- ^ Frontani 2007, p. 161.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 283.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 151.

- ^ Harry 2003, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d Lewisohn 2005, p. 128.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 232.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 138, 144, 340.

- ^ Stark 2005, p. 220.

- ^ Reck 2008, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Barrow 1999.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 280–82.

- ^ a b c Lewisohn 2005, p. 130.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 176.

- ^ a b c d Everett 1999, p. 142.

- ^ Carr & Tyler 1978, p. 70.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 189.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 600–01.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 129.

- ^ a b Hertsgaard 1996, p. 167.

- ^ Prendergast 2003, p. 194.

- ^ Reising & LeBlanc 2009, pp. 94, 98–99.

- ^ a b Guesdon & Margotin 2013, p. 430.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, pp. 166–67.

- ^ MacFarlane 2008, p. 40.

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2013, p. 436.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 156–57.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, p. 122.

- ^ a b c d Everett 1999, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Guesdon & Margotin 2013, p. 437.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 123.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Everett 1999, p. 138.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 127.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 182.

- ^ Everett 2006, p. 88.

- ^ MacFarlane 2008, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lewisohn 2005, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d Neaverson 1997, p. 53.

- ^ Larkin 2006, p. 488.

- ^ Chapman 2015, p. 298.

- ^ Reising & LeBlanc 2009, pp. 102–03, 105–06.

- ^ Reck 2008, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 109–10.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 103.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 684.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, p. 121.

- ^ a b Gould 2007, p. 454.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 224.

- ^ Miles 1997, p. 355.

- ^ a b Greene 2016, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Greene 2016, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 721.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 443–45.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 133.

- ^ Courrier 2009, p. 191.

- ^ a b MacDonald 2005, p. 267.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 444.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 121.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 455.

- ^ Everett 1999, pp. 138, 139–40.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 343, 365–66.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 280–81.

- ^ Ingham 2006, pp. 200–01.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 282.

- ^ Brown & Gaines 2002, p. 254.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 123, 127.

- ^ Courrier 2009, p. 193.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 131.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 278.

- ^ Unterberger 2006, p. 180.

- ^ a b Schaffner 1978, p. 91.

- ^ a b Miles 2001, p. 286.

- ^ Courrier 2009, p. 194.

- ^ MacDonald, Ian (2002). "The Psychedelic Experience". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days That Shook the World (The Psychedelic Beatles – April 1, 1965 to December 26, 1967). London: Emap. pp. 35–36.

- ^ Everett 1999, p. 340.

- ^ Reck 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Miles 2001, pp. 285–86.

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2013, p. 422.

- ^ Greene 2016, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Winn 2009, pp. 164–65.

- ^ Spangler, Jay. "John Lennon & Paul McCartney: Apple Press Conference 5/14/1968". Beatles Interviews Database. Archived from the original on 24 June 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 1053.

- ^ a b Schaffner 1978, p. 92.

- ^ Shaar Murray 2002, pp. 130–31.

- ^ a b Shaar Murray 2002, p. 130.

- ^ Black 2002, p. 138.

- ^ Magical Mystery Tour (EP booklet). The Beatles. Parlophone/NEMS Enterprises. 1967. p. 1.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link) - ^ Neaverson 1997, p. 54.

- ^ Gould 2007, p. 452.

- ^ a b Womack 2014, p. 598.

- ^ Kubernik 2014, pp. 127–28.

- ^ Kubernik 2014, pp. 128–29.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 452–53.

- ^ Kubernik 2014, pp. 129–30.

- ^ a b c Schaffner 1978, p. 127.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 597–98.

- ^ a b c Miles 2001, p. 284.

- ^ a b Winn 2009, pp. 138–39.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 138.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 285.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 602.

- ^ Billboard staff (25 November 1967). "Beatles' 13th Cap. LP Due Mid-December". Billboard. p. 6. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ Hertsgaard 1996, p. 229.

- ^ Neaverson 1997, p. 71.

- ^ Miles 1997, pp. 368–69.

- ^ Frontani 2007, pp. 161–62.

- ^ a b c Everett 1999, p. 132.

- ^ Chapman 2015, p. 303.

- ^ Harry 2000, p. 699.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 359.

- ^ Spitz 2005, p. 844.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 281.

- ^ "Grammy Awards 1969". Awards and Shows. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, p. 97.

- ^ "Official Singles Chart Top 50: 10 January 1968 – 16 January 1968". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 46.

- ^ a b Bagirov 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 338.

- ^ Datablog (9 September 2009). "The Beatles: Every album and single, with its chart position". theguardian.com. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Kronemyer, David (29 April 2009). "How Many Records did the Beatles actually sell?". Deconstructing Pop Culture. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- ^ Heylin 2007, p. 245.

- ^ Harris, John (2003). "Cruel Britannia". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days of Revolution (The Beatles' Final Years – Jan 1, 1968 to Sept 27, 1970). London: Emap. p. 44.

- ^ Doggett 2011, p. 32.

- ^ Greene 2016, p. 42.

- ^ Ingham 2006, p. 48.

- ^ Logan, Nick (25 November 1967). "Sky-High with Beatles". NME. p. 14.

- ^ Sutherland, Steve, ed. (2003). NME Originals: Lennon. London: IPC Ignite!. p. 51.

- ^ Jopling, Norman (1 December 1967). "Magical Mystery Beatles". Record Mirror. p. 1.

- ^ Jahn, Mike (December 1967). "The Beatles: Magical Mystery Tour". Saturday Review. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Staff writer (April 1968). "Platter Chatter: Albums from The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Jefferson Airplane, Cream and Kaleidoscope". Hit Parader. Available at Rock's Backpages Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine (subscription required).

- ^ Frontani 2007, p. 208.

- ^ "Album Reviews". Rolling Stone. 20 January 1968. p. 21. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- ^ Miles 2001, p. 220.

- ^ Schaffner 1978, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (31 December 1967). "Are the Beatles Waning?". The New York Times. p. 62. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Reed, Rex (March 1968). "Entertainment (The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour)" (PDF). HiFi/Stereo Review. p. 117. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (May 1968). "Columns: Dylan-Beatles-Stones-Donovan-Who, Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield, John Fred, California". robertchristgau.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ a b Unterberger, Richie. "The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ a b Du Noyer, Paul (2004). "The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour". Blender. Archived from the original on 4 May 2006. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- ^ Caffrey, Dan (23 September 2009). "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour (Remastered)". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ a b McCormick, Neil (7 September 2009). "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour, review". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ Larkin 2006, p. 489.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 88. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- ^ a b Kemp, Mark (8 September 2009). "The Beatles: The Long and Winding Repertoire". Paste. pp. 58–59. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- ^ a b Plagenhoef, Scott (9 September 2009). "The Beatles Magical Mystery Tour". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- ^ Brackett & Hoard 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Med57 (14 April 2005). "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". Sputnikmusic. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Brackett & Hoard 2004, p. 53.

- ^ Shaar Murray 2002, pp. 128, 130.

- ^ Shaar Murray 2002, p. 128.

- ^ Gould 2007, pp. 453, 454.

- ^ Ingham 2006, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Heylin 2007, p. 265.

- ^ Leopold, Todd (7 March 2007). "A Really Infuriating Top 200 List" Archived 22 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine.The Marquee at CNN.com. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 134. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Prendergast 2003, p. 196.

- ^ Prendergast 2003, p. 478.

- ^ Christgau, Robert; Fricke, David (12 July 2007). "The 40 Essential Albums of 1967". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ "Magical Mystery Tour Reconsidered ... In True Stereo » Rock Town Hall". 16 August 2007. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ^ Carr & Tyler 1978, p. 121.

- ^ Womack 2014, pp. 107–08.

- ^ Bagirov 2008, p. 110.

- ^ Heylin 2007, p. 276.

- ^ Blackard, Cap (27 September 2009). "Album Review: the Beatles – Past Masters [Remastered] « Consequence of Sound". Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Billboard magazine, week ending 27 October 2012.

- ^ Castleman & Podrazik 1976, p. 63.

- ^ Womack 2014, p. 278.

- ^ Lewisohn 2005, pp. 88–93, 110–11, 116–30.

- ^ MacDonald 2005, pp. 212–23, 253–59, 261–73.

- ^ Winn 2009, p. 131.

- ^ Guesdon & Margotin 2013, p. 410.

- ^ "Go-Set National Top 40". poparchives.com.au. 1 May 1968. Archived from the original on 6 March 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Search: 'Magical Mystery Tour'". irishcharts.ie. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Search NZ Listener > 'The Beatles'". Flavour of New Zealand/Steve Kohler. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour (Song)". norwegiancharts.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Swedish Charts 1966–1969/Kvällstoppen – Listresultaten vecka för vecka > Januari 1968" (PDF) (in Swedish). hitsallertijden.nl. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". hitparade.ch. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b Nyman, Jake (2005). Suomi soi 4: Suuri suomalainen listakirja (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Helsinki: Tammi. ISBN 951-31-2503-3.

- ^ "Magical Mystery Tour (EP)". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Langspielplatten Hit-Parade (15 April 1968)". musikmarkt.de. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". austriancharts.at. Archived from the original on 25 January 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". ultratop.be. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". ultratop.be. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Dutch Album Top 100 (26/09/2009)". dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". finishcharts.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". italiancharts.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ ザ・ビートルズ"リマスター"全16作トップ100入り「売上金額は23.1億円」 ["All of the Beatles' 'Remastered' Albums Enter the Top 100: Grossing 2,310 Million Yen in One Week"]. Oricon Style (in Japanese). 15 September 2009. Archived from the original on 9 March 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Album Top 40 (14/09/2009)". charts.nz. Archived from the original on 21 May 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "Portuguese Charts: Albums – 38/2009". portuguesecharts.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". spanishcharts.com. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". swedishcharts.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". hitparade.ch. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ a b c "Magical Mystery Tour" > "Chart Facts". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". charts.nz. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour (Album)". norwegiancharts.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- ^ "The Beatles: Awards". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- ^ "Cash Box Top 100 Albums (January 20, 1968)". Cash Box. 20 January 1968. p. 59.

- ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2009 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". Music Canada. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (The Beatles; 'Magical Mystery Tour')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie.

- ^ Murrells, Joseph (1985). Million selling records from the 1900s to the 1980s : an illustrated directory. Arco Pub. p. 235. ISBN 0668064595.

The Parlaphone two-EP issue in Britain of the six songs from Magical Mystery Tour had advance orders of 400,000, over 600,000 sold by mid-January 1968

- ^ "British album certifications – The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "American album certifications – The Beatles – Magical Mystery Tour". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 15 September 2013.

- ^ "Beatles albums finally go platinum". British Phonographic Industry. BBC News. 2 September 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

Sources

edit- Bagirov, Alex (2008). The Anthology of the Beatles Records. Rostock: Something Books. ISBN 978-3-936300-44-4.

- Barrow, Tony (1999). The Making of The Beatles' Magical Mystery Tour. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-7575-2. No page numbers appear.

- Black, Johnny (2002). "Roll Up, Roll Up for the Mystery Tour". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days That Shook the World (The Psychedelic Beatles – April 1, 1965 to December 26, 1967). London: Emap. pp. 132–38.

- Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian, eds. (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide. New York, NY: Fireside/Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Brown, Peter; Gaines, Steven (2002) [1983]. The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of the Beatles. New York, NY: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-20735-7.

- Carr, Roy; Tyler, Tony (1978). The Beatles: An Illustrated Record. London: Trewin Copplestone Publishing. ISBN 0-450-04170-0.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Chapman, Rob (2015). Psychedelia and Other Colours. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-28200-5. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- Courrier, Kevin (2009). Artificial Paradise: The Dark Side of the Beatles' Utopian Dream. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-34586-9.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup. New York, NY: It Books. ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8.

- Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512941-5.

- Everett, Walter (2006). "Painting Their Room in a Colorful Way". In Womack, Kenneth; Davis, Todd F. (eds.). Reading the Beatles: Cultural Studies, Literary Criticism, and the Fab Four. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-6716-3.

- Frontani, Michael R. (2007). The Beatles: Image and the Media. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-966-8.

- Gould, Jonathan (2007). Can't Buy Me Love: The Beatles, Britain and America. London: Piatkus. ISBN 978-0-7499-2988-6.

- Greene, Doyle (2016). Rock, Counterculture and the Avant-Garde, 1966–1970: How the Beatles, Frank Zappa and the Velvet Underground Defined an Era. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-6214-5.

- Guesdon, Jean-Michel; Margotin, Philippe (2013). All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Beatles Release. New York, NY: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-1-57912-952-1.

- Harry, Bill (2000). The Beatles Encyclopedia. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0481-9.

- Harry, Bill (2003). The George Harrison Encyclopedia. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-7535-0822-0.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Heylin, Clinton (2007). The Act You've Known for All These Years: A Year in the Life of Sgt. Pepper and Friends. New York, NY: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-918-4.

- Ingham, Chris (2006). The Rough Guide to the Beatles. London: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-720-5.

- Kubernik, Harvey (2014). It Was Fifty Years Ago Today: The Beatles Invade America and Hollywood. Los Angeles, CA: Otherworld Cottage Industries. ISBN 978-0-9898936-8-8.

- Larkin, Colin (2006). Encyclopedia of Popular Music. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- Lewisohn, Mark (2005) [1988]. The Complete Beatles Recording Sessions: The Official Story of the Abbey Road Years 1962–1970. London: Bounty Books. ISBN 978-0-7537-2545-0.

- MacDonald, Ian (2005). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties (2nd rev. edn). Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-733-3.

- MacFarlane, Thomas (2008). "Sgt. Pepper's Quest for Extended Form". In Julien, Olivier (ed.). Sgt. Pepper and the Beatles: It Was Forty Years Ago Today. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6249-5. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Miles, Barry (1997). Paul McCartney: Many Years From Now. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0-8050-5249-6.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- Neaverson, Bob (1997). The Beatles Movies. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-33796-5. (Text also available, in three parts, at beatlesmovies.co.uk.)

- Prendergast, Mark (2003). The Ambient Century: From Mahler to Moby – The Evolution of Sound in the Electronic Age. New York, NY: Bloomsbury. ISBN 1-58234-323-3.

- Reck, David (2008). "The Beatles and Indian Music". In Julien, Olivier (ed.). Sgt. Pepper and the Beatles: It Was Forty Years Ago Today. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6249-5. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- Reising, Russell; LeBlanc, Jim (2009). "Magical Mystery Tours, and Other Trips: Yellow submarines, newspaper taxis, and the Beatles' psychedelic years". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Shaar Murray, Charles (2002). "Magical Mystery Tour: All Aboard the Magic Bus". Mojo Special Limited Edition: 1000 Days That Shook the World (The Psychedelic Beatles – April 1, 1965 to December 26, 1967). London: Emap. pp. 128–31.

- Spitz, Bob (2005). The Beatles: The Biography. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 1-84513-160-6.

- Stark, Steven D. (2005). Meet the Beatles: A Cultural History of the Band That Shook Youth, Gender, and the World. New York, NY: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-000893-2. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Unterberger, Richie (2006). The Unreleased Beatles: Music & Film. San Francisco, CA: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-892-6.

- Winn, John C. (2009). That Magic Feeling: The Beatles' Recorded Legacy, Volume Two, 1966–1970. New York, NY: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-307-45239-9.

- Womack, Kenneth (2014). The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-39171-2.

External links

edit- Magical Mystery Tour (UK EP) at Discogs (list of releases)

- Magical Mystery Tour (US LP) at Discogs (list of releases)

- Beatles comments on each song

- Recording data and notes on mono/stereo mixes and remixes

- The real Blue Jay Way