Lesser Poland Voivodeship (Polish: województwo małopolskie [vɔjɛˈvut͡stfɔ mawɔˈpɔlskʲɛ] ) is a voivodeship in southern Poland. It has an area of 15,108 square kilometres (5,833 sq mi), and a population of 3,404,863 (2019).[3]

Lesser Poland Voivodeship

Województwo małopolskie | |

|---|---|

Location within Poland | |

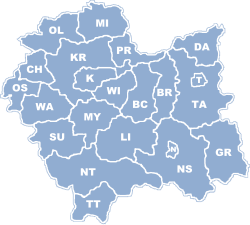

Division into counties | |

| Coordinates (Kraków): 50°3′41″N 19°56′18″E / 50.06139°N 19.93833°E | |

| Country | |

| Capital | Kraków |

| Counties | 3 cities, 19 land counties * |

| Government | |

| • Body | Executive board |

| • Voivode | Krzysztof Klęczar (PSL) |

| • Marshal | Łukasz Smółka (PiS) |

| • EP | Lesser Poland and Świętokrzyskie |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,108 km2 (5,833 sq mi) |

| Population (2019) | |

| • Total | 3,404,863 |

| • Density | 230/km2 (580/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,641,189 |

| • Rural | 1,763,674 |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €47.231 billion |

| • Per capita | €14,100 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | PL-12 |

| Vehicle registration | K |

| HDI (2021) | 0.888[2] very high · 3rd |

| Primary airport | Kraków John Paul II International Airport |

| Highways | |

| Website | www |

| |

The province's name recalls the traditional name of a historic Polish region, Lesser Poland, or in Polish: Małopolska. Current Lesser Poland Voivodeship, however, covers only a small part of the broader ancient Małopolska region. Historic Lesser Poland is much larger than the current province. It stretches far north, to Radom, and Siedlce, also including such cities, as Lublin, Kielce, Częstochowa, and Sosnowiec.

The province is bounded on the north by the Świętokrzyskie Mountains (Góry Świętokrzyskie), on the west by Jura Krakowsko-Częstochowska (a broad range of hills stretching from Kraków to Częstochowa), and on the south by the Tatra, Pieniny and Beskidy Mountains. Politically it is bordered by Silesian Voivodeship to the west, Świętokrzyskie Voivodeship to the north, Subcarpathian Voivodeship to the east, and Slovakia (Prešov Region and Žilina Regions) to the south.

Almost all of Lesser Poland lies in the Vistula River catchment area. The city of Kraków was one of the European Cities of Culture in 2000. Kraków has railway and road connections with Katowice (expressway), Warsaw, Wrocław and Rzeszów. It lies at the crossroads of major international routes linking Dresden with Kyiv, and Gdańsk with Budapest. Located here is the second largest international airport in Poland (after Warsaw's), the John Paul II International Airport.

Economy

editThe gross domestic product (GDP) of the province was €40.4 billion in 2018, accounting for 8.1% of the Polish economic output. GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power was €19,700 or 65% of the EU27 average in the same year. The GDP per employee was 72% of the EU average.[4]

The region's economy includes high technology, banking, chemical and metallurgical industries, coal, ore, food processing, and spirit and tobacco industries. The most industrialized city of the voivodeship is Kraków. The largest regional enterprise operates here, the Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks in Nowa Huta, employing 17,500 people. Another major industrial center is located in the west, in the neighborhood of Chrzanów (chiefly the production of railway engines) and Oświęcim (chemical works). Kraków Park Technologiczny, a special economic zone, has been established within the voivodeship. There are almost 210,000 registered economic entities operating in the voivodeship, mostly small and medium-sized, of which 234 belong to the state-owned sector. Foreign investment, growing in the region, reached approximately US$18.3 billion by the end of 2006.

Universities

editA total of 130,000 students attend fifteen Kraków institutions of higher learning. The Jagiellonian University, the largest university in the city (44,200 students), was founded in 1364 as Cracow Academy. Nicolaus Copernicus and Karol Wojtyła (Pope John Paul II) graduated from it. The AGH University of Science and Technology (29,800 students) is considered to be the best technical university in Poland. The Academy of Economics, the Pedagogical University, the Kraków University of Technology and the Agricultural Academy are also very highly regarded. There are also the Fine Arts Academy, the State Theatre University and the Musical Academy. Nowy Sącz has become a major educational center in the region thanks to its Higher School of Business and Administration, with an American curriculum, founded in 1992. The school has 4,500 students. There are also two private higher schools in Tarnów.

History

editIn the Early Middle Ages, the territory was inhabited by the Vistulans, an old Polish tribe. It formed part of Poland since its establishment in the 10th century, with the regional capital Kraków becoming the seat of one of Poland's oldest dioceses, est. in 1000, contributing to the Christianization of Poland. In 1038, Kraków became the capital of Poland by decision of Casimir I the Restorer, retaining its role for several centuries with short-term breaks. It also became the location of the Jagiellonian University, Poland's oldest university and one of world's oldest, established by King Casimir III the Great. In the Late Middle Ages, Oświęcim and Zator were ducal seats of local lines of the Piast dynasty. Following the late-18th-century Partitions of Poland, the region witnessed several uprisings against foreign rule, i.e. the Kościuszko Uprising of 1794, Kraków uprising of 1846 and January Uprising of 1863–1864, and Kraków remained one of the main cultural centers of partitioned Poland, taking advantage of the more relaxed policies of the Austrian partitioners than those of the Prussians and Russians. In the interbellum, the region was part of reborn independent Poland.

During World War II, it was occupied by Germany, with the occupiers committing their genocidal policies against Poles and Jews in the region, massacring civilians and prisoners of war, including at Szczucin and Olkusz, operating prisons, forced labour camps and, most notably, the Auschwitz concentration camp with a network of subcamps in various localities. There was also a German prisoner-of-war camp for French, Belgian, Dutch and Soviet prisoners of war.[5][6]

The Lesser Poland Voivodeship was created on 1 January 1999 out of the former Kraków, Tarnów, Nowy Sącz and parts of Bielsko-Biała, Katowice, Kielce and Krosno Voivodeships, pursuant to the Polish local government reforms adopted in 1998.

Climate

editLocated in Southern Poland, Lesser Poland is the warmest place in Poland with average summer temperatures between 23 °C (73 °F) and 30 °C (86 °F) during the day, often reaching 32 °C (90 °F) to 38 °C (100 °F) in July and August, the two warmest months of the year. The city of Tarnów, which is located in Lesser Poland, is the hottest place in Poland all year round, average temperatures being around 25 °C (77 °F) during the day in the three summer months and 3 °C (37 °F) during the day in the three winter months. In the winter the weather patterns alter each year; usually winters are mildly cold with temperatures ranging from −7 °C (19 °F) to 4 °C (39 °F), but the winter season changes often to a more humid and warmer winter, or more continental and cold, depending on the many various wind patterns that affect Poland from different regions of the world. Błędów Desert, the only desert in Poland, is located in Lesser Poland, where temperatures can often reach 38 °C (100 °F) in the summer.

Tourism

editLesser Poland Voivodeship is the voivodeship with the highest number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Poland with six entries, encompassing the Kraków Old Town with the Wawel Royal Castle, former main royal residence and burial site of Polish monarchs, the old salt mines of Bochnia (Europe's oldest) and Wieliczka, the pilgrimage town of Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, the former Nazi German concentration camp Auschwitz in Oświęcim, the wooden churches of Southern Lesser Poland, and the wooden Tserkvas of the Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine.

Four national parks and numerous reserves have been established in the voivodeship to protect the environment of Lesser Poland. The region has areas for tourism and recreation, including Zakopane (Poland's most popular winter resort) and the Tatra, Pieniny and Beskidy Mountains. There are ten spa towns: Krynica-Zdrój, Muszyna, Piwniczna-Zdrój, Rabka-Zdrój, Szczawnica, Wapienne, Wieliczka, Wysowa-Zdrój, Zakopane, Żegiestów. The natural landscape features many historic sites.

The voivodeship is rich in historic architecture ranging from Romanesque and Gothic to Renaissance, Baroque and Art Nouveau. Numerous towns possess preserved historic market squares and town halls, as in Kraków and Tarnów. At Wadowice, birthplace of John Paul II (50 kilometers southwest of Kraków) is a museum dedicated to the late pope's childhood.

The voivodeship, especially Kraków, is home to various museums, art galleries and cultural institutions. Major museums include the National Museum in Kraków with the branch Czartoryski Museum, one of the oldest museums of Poland, which contains works by various artists including Leonardo da Vinci, Rembrandt and Kraków-native Jan Matejko, and the Archaeological Museum of Kraków, the oldest archaeological museum in Poland. There are museums dedicated to painters Jan Matejko and Józef Mehoffer at their former homes in Kraków, to composer and pianist Karol Szymanowski and writer Kornel Makuszyński at their homes in Zakopane, to writer Władysław Orkan at his home in Poręba Wielka and to writer Emil Zegadłowicz in his manor in Gorzeń Górny. Manggha, the largest Polish museum of Japanese art, is located in Kraków.

There are numerous World War II memorials in the province, including a museum at the site of the former Nazi concentration camps Auschwitz-I and Auschwitz-II-Birkenau, as well as the Auschwitz Jewish Center, visited annually by a million people. There are memorials at the sites of German-perpetrated massacres of Poles, German-operated forced labour camps, etc.

The voivodeship is abundant in castles, including Mirów, Niedzica, Niepołomice, Nowy Wiśnicz, Pieskowa Skała and Wawel.

List of cities and towns

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1988 | 3,087,613 | — |

| 2002 | 3,232,408 | +4.7% |

| 2011 | 3,337,471 | +3.3% |

| 2021 | 3,432,995 | +2.9% |

| Source: [7] | ||

The voivodeship contains 4 cities and 58 towns. These are listed below in descending order of population (according to official figures for 2019[3]):

Towns:

- Chrzanów (36,717)

- Olkusz (35,421)

- Nowy Targ (33,357)

- Bochnia (29,814)

- Gorlice (27,442)

- Zakopane (27,078)

- Skawina (24,340)

- Andrychów (20,143)

- Kęty (18,705)

- Wadowice (18,778)

- Wieliczka (23,565)

- Trzebinia (19,778)

- Myślenice (18,349)

- Libiąż (17,017)

- Brzesko (16,792)

- Limanowa (15,157)

- Rabka-Zdrój (12,746)

- Brzeszcze (11,185)

- Miechów (11,612)

- Dąbrowa Tarnowska (11,889)

- Krynica-Zdrój (10,635)

- Bukowno (10,141)

- Krzeszowice (10,014)

- Sucha Beskidzka (9,114)

- Wolbrom (8,561)

- Chełmek (9,073)

- Stary Sącz (9,071)

- Niepołomice (13,276)

- Mszana Dolna (7,944)

- Szczawnica (5,732)

- Tuchów (6,627)

- Sułkowice (6,637)

- Proszowice (5,976)

- Dobczyce (6,444)

- Grybów (6,026)

- Maków Podhalański (5,841)

- Piwniczna-Zdrój (5,884)

- Jordanów (5,346)

- Muszyna (4,800)

- Biecz (4,590)

- Kalwaria Zebrzydowska (4,496)

- Słomniki (4,343)

- Żabno (4,234)

- Szczucin (4,157)

- Zator (3,677)

- Skała (3,798)

- Alwernia (3,368)

- Wojnicz (3,328)

- Bobowa (3,136)

- Radłów (2,765)

- Ryglice (2,839)

- Nowy Wiśnicz (2,757)

- Ciężkowice (2,473)

- Czchów (2,345)

- Świątniki Górne (2,431)

- Nowe Brzesko (1,663)

- Zakliczyn (1,631)

- Koszyce (779)

Administrative division

editLesser Poland Voivodeship is divided into 22 counties (powiats): 3 city counties and 19 land counties. These are further divided into 182 gminas.

The counties are listed in the following table (ordering within categories is by decreasing population).

| English and Polish names |

Area (km2) |

Population (2019) |

Seat | Other towns | Total gminas |

| City counties | |||||

| Kraków | 327 | 774,839 | 1 | ||

| Tarnów | 72 | 108,580 | 1 | ||

| Nowy Sącz | 57 | 83,813 | 1 | ||

| Land counties | |||||

| Kraków County powiat krakowski |

1,230 | 278,219 | Kraków * | Skawina, Krzeszowice, Słomniki, Skała, Świątniki Górne | 17 |

| Nowy Sącz County powiat nowosądecki |

1,550 | 216,429 | Nowy Sącz * | Krynica-Zdrój, Stary Sącz, Grybów, Piwniczna-Zdrój, Muszyna | 16 |

| Tarnów County powiat tarnowski |

1,413 | 201,509 | Tarnów * | Tuchów, Żabno, Wojnicz, Radłów, Ryglice, Ciężkowice, Zakliczyn | 16 |

| Nowy Targ County powiat nowotarski |

1,475 | 191,669 | Nowy Targ | Rabka-Zdrój, Szczawnica | 14 |

| Wadowice County powiat wadowicki |

646 | 160,080 | Wadowice | Andrychów, Kalwaria Zebrzydowska | 10 |

| Oświęcim County powiat oświęcimski |

406 | 153,632 | Oświęcim | Kęty, Brzeszcze, Chełmek, Zator | 9 |

| Chrzanów County powiat chrzanowski |

371 | 124,937 | Chrzanów | Trzebinia, Libiąż, Alwernia | 5 |

| Limanowa County powiat limanowski |

952 | 131,729 | Limanowa | Mszana Dolna | 12 |

| Myślenice County powiat myślenicki |

673 | 127,262 | Myślenice | Sułkowice, Dobczyce | 9 |

| Olkusz County powiat olkuski |

622 | 111,655 | Olkusz | Bukowno, Wolbrom | 6 |

| Gorlice County powiat gorlicki |

967 | 108,938 | Gorlice | Biecz, Bobowa | 10 |

| Wieliczka County powiat wielicki |

428 | 127,970 | Wieliczka | Niepołomice | 5 |

| Bochnia County powiat bocheński |

649 | 106,626 | Bochnia | Nowy Wiśnicz | 9 |

| Brzesko County powiat brzeski |

590 | 93,139 | Brzesko | Czchów | 7 |

| Sucha County powiat suski |

686 | 84,160 | Sucha Beskidzka | Maków Podhalański, Jordanów | 9 |

| Tatra County powiat tatrzański |

472 | 68,135 | Zakopane | 5 | |

| Dąbrowa County powiat dąbrowski |

530 | 59,227 | Dąbrowa Tarnowska | Szczucin | 7 |

| Miechów County powiat miechowski |

677 | 48,948 | Miechów | 7 | |

| Proszowice County powiat proszowicki |

415 | 43,367 | Proszowice | Nowe Brzesko, Koszyce | 6 |

| * seat not part of the county | |||||

Protected areas

editProtected areas in Lesser Poland Voivodeship include six National Parks and 11 Landscape Parks. These are listed below.

- Babia Góra National Park (a UNESCO-designated biosphere reserve)

- Gorce National Park

- Magura National Park (partly in Subcarpathian Voivodeship)

- Ojców National Park

- Pieniny National Park

- Tatra National Park (part of a UNESCO biosphere reserve shared with Slovakia)

- Bielany-Tyniec Landscape Park

- Ciężkowice-Rożnów Landscape Park

- Dłubnia Landscape Park

- Eagle Nests Landscape Park (partly in Silesian Voivodeship)

- Kraków Valleys Landscape Park

- Little Beskids Landscape Park (partly in Silesian Voivodeship)

- Pasmo Brzanki Landscape Park (partly in Subcarpathian Voivodeship)

- Poprad Landscape Park

- Rudno Landscape Park

- Tenczynek Landscape Park

- Wiśnicz-Lipnica Landscape Park

Symbols

editLesser Poland Voivodeship's symbols can be blazoned as follows:

Coat of arms: A traditional Iberian shield gules, an eagle argent displayed armed, legged, beaked, langued and crowned Or.

Flag: Per fess argent and gules, a narrow fess Or.

Cuisine

editIn addition to traditional nationwide Polish cuisine, the voivodeship is known for its variety of regional and local traditional foods, which include especially various cheeses, including the Bundz, Oscypek and Bryndza Podhalańska from mountain areas, meat products, especially local types of kiełbasa and bacon, honeys and various dishes and meals, officially protected by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Poland. There are local types of pierogi, kluski, kołacz and various soups. Local specialities include obwarzanek krakowski and krówki from Regulice.[8]

Local beverages include several types of nalewki and śliwowica, including Śliwowica łącka.

Most popular surnames in the region

editInternational relations

editThe Lesser Poland Voivodeships has partnerships with the following regions:[9]

- Thuringia (Germany)

- Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes (France)

- Prešov Region (Slovakia)

- Žilina Region (Slovakia)

- Lviv Oblast (Ukraine)

- Cluj County (Romania)

- Sverdlovsk Oblast (Russia)

- Latgale, (Latvia)

- Jiangsu, (China)

- Andhra Pradesh, (India)

- Uppsala County, (Sweden)

- Kurdistan Region, (Iraq)

- Istria County, (Croatia)

- Adjara, (Georgia)

In February 2020, the French region of Centre-Val de Loire suspended its partnership with the Lesser Poland Voivodeship as a response to the anti-LGBT resolution passed by the voivodeship's authorities.[10][11][12] In September 2021, the voivodeships's authorities revoked the controversial declaration.[13]

Sports

editFootball, ice hockey and motorcycle speedway enjoy the largest following and greatest success in the voivodeship. Cracovia and Wisła Kraków contest the Kraków Derby, nicknamed the Holy War, considered the fiercest rivalry in Poland and one of the fiercest in Europe. Most accomplished hockey teams are Podhale Nowy Targ, Cracovia and Unia Oświęcim. Top speedway team is Unia Tarnów.

Since the establishment of the province, various major international sports competitions were co-hosted by the province, including the 2014 FIVB Volleyball Men's World Championship, 2016 European Men's Handball Championship, 2017 Men's European Volleyball Championship, 2021 Men's European Volleyball Championship, 2023 World Men's Handball Championship, 2023 European Games.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "EU regions by GDP, Eurostat". Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI". Global Data Lab. Radboud University Nijmegen. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

- ^ a b GUS. "Population. Size and structure and vital statistics in Poland by territorial division in 2019. As of 30th June". stat.gov.pl. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- ^ Banaś, Jan; Fijałkowska, Grażyna (2006). Miejsca Pamięci Narodowej na terenie Podgórza (in Polish). Kraków. p. 30.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; Overmans, Rüdiger; Vogt, Wolfgang (2022). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos 1933–1945. Volume IV. Indiana University Press, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-253-06089-1.

- ^ "Statistics Poland - National Censuses".

- ^ "Krówka regulicka". Ministerstwo Rolnictwa i Rozwoju Wsi - Portal Gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Współpraca międzynarodowa". Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Francuski region zawiesza współpracę z Małopolską. "Jawnie homofobiczna deklaracja"". Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Rivaud, François-Xavier (2020-03-02). "Zones anti-LGBT : la région Centre - Val-de-Loire rompt avec la Pologne". Le Parisien. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ ""Zones anti-LGBT" : la région Centre-Val de Loire suspend sa coopération avec Malopolska en Pologne". Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ "Sukces demokratycznej opozycji: Sejmik uchylił deklarację anty-LGBT" (in Polish). Retrieved 27 September 2021.

References

edit- Małopolskie Voivodship official site

- Photo- and Topographic Maps of the whole region

- Poland - Climate

- Agency for Regional Development of Lesser Poland - MARR

- Tourism Information of Małopolskie Voivodship

- Małopolska Province invites

- Photos of Krakow, Tatry, Zakopane

- Info about the Smaller Poland - Malopolska Province

External links

edit- Lesser Poland Voivodeship travel guide from Wikivoyage