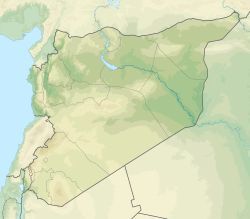

Maarat al-Numan (Arabic: مَعَرَّةُ النُّعْمَانِ, romanized: Maʿarrat an-Nuʿmān), also known as al-Ma'arra, is a city in northwestern Syria, 33 km (21 mi) south of Idlib and 57 km (35 mi) north of Hama, with a population of about 58,008 before the Civil War (2004 census). In 2017, it was estimated to have a population of 80,000, including several displaced by fighting in neighbouring towns.[1] It is located on the highway between Aleppo and Hama and near the Dead Cities of Bara and Serjilla.

Maarat al-Numan

مَعَرَّةُ النُّعْمَانِ | |

|---|---|

A collage of Maarat al-Numan landmarks | |

| Coordinates: 35°38′N 36°40′E / 35.633°N 36.667°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Idlib |

| District | Maarat al-Numan |

| Subdistrict | Maarat al-Numan |

| Control | |

| Elevation | 522 m (1,713 ft) |

| Population (2009) | |

• Total | 87,742 |

| Demonym(s) | Arabic: معري, romanized: Maarri |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (EEST) |

| Geocode | C3985 |

| Climate | BSk |

Name

editThe city, known as Arra to the Greeks, has its present-day name combined from the Aramaic word for cave ܡܥܪܗ (mʿarā) and that of its first Muslim governor, Nu'man ibn Bashir al-Ansari, a companion of Muhammad, meaning “the Cave of Nu’man.” The crusaders called it Marre. There are many towns throughout Syria with names that begin with the word Maarat, such as Maarrat Misrin and Maarat Saidnaya.

History

editAbbasids to Fatimids (891–1086)

editIn 891 Ya‘qubi described Maarrat al-Nu‘man as "an ancient city, now a ruin. It lies in the Hims province."[2] By the time of Estakhri (951) the place had recovered, as he described the city "very full of good things, and very opulent". Figs, pistachios and vines were cultivated.[2] In 1047 Nasir Khusraw visited the city, and described it as a populous town with a stone wall. There was a Friday Mosque, on a height, in the middle of the town. The bazaars were full of traffic. Considerable areas of cultivated land surrounded the town, with plenty of fig-trees, olives, pistachios, almonds and grapes.[2][3]

Crusader Ma‘arra massacre (1098)

editThe most infamous event from the city's history dates from late 1098, during the First Crusade. After the crusaders, led by Raymond de Saint Gilles and Bohemond of Taranto, successfully besieged Antioch they found themselves with insufficient supplies of food. During or after the siege of Ma‘arra some of the starving crusaders therefore resorted to cannibalism, feeding on the bodies of Muslims. This fact itself is not seriously in doubt, as it is acknowledged by nearly a dozen Christian chronicles written during the twenty years after the Crusade, all of which are based at least to some degrees on eyewitness accounts.[4] The crusaders' cannibalism is also briefly mentioned in an Arab source, which explains it as due to hunger.[5]

There is conflicting evidence on when exactly and why the cannibalism happened. Some sources state that enemies were eaten during the siege, others (a slight majority) state that it happened after the city had been conquered.[6] Another source of tension exists regarding its motives – was it practised secretly due to famine and lack of food, as some sources suggest, or publicly in front of the enemies in order to shock and frighten them, as others imply?[7]

The earliest of the texts suggesting that the cannibalism occurred after the end of the siege and was entirely motivated by hunger is the Gesta Francorum. It states that because of great deprivations after the siege, "Some cut the flesh of dead bodies into strips and cooked them for eating." Peter Tudebode's chronicle gives a similar description, though adding that only Muslims were eaten.[8] Several other works include similar accounts, likewise stating that only Muslims or "Turks" were consumed.[9]

Three other accounts, by Fulcher of Chartres (who was a participant of the Crusade though not personally present at Ma‘arra), Albert of Aachen and Ralph of Caen (both of whom based their accounts on interviews with participants) state that the cannibalism happened during the siege and suggest that it was a public spectacle rather than a shameful, hidden episode.[10] Ralph states that "a lack of food compelled them to make a meal of human flesh, that adults were put in the stewpot, and that [children] were skewered on spits. Both were cooked and eaten."[11]

Several medieval interpretations of the cannibalism during the Crusade, by Guibert of Nogent, William of Tyre, and in the Chanson d'Antioche, interpret it as an deliberate act of psychological warfare, "intended to strike fear in the enemy". This implies it must have happened during rather than after the siege, "while there were still Muslims alive to witness it and to feel the horror that was its intended by-product".[12]

Some chroniclers as well as various later sources blame the cannibalism at Ma'arra at the Tafurs, a group of crusaders who followed strict oaths of poverty. One interpretation in this tradition is the French poem The Leaguer of Antioch, which contains lines such as:

- Then came to him the King Tafur, and with him fifty score

- Of men-at-arms, not one of them but hunger gnawed him sore.

- Thou holy Hermit, counsel us, and help us at our need;

- Help, for God's grace, these starving men with wherewithal to feed.

- But Peter answered, 'Out, ye drones, a helpless pack that cry,

- While all unburied round about the slaughtered Paynim lie.

- A dainty dish is Paynim flesh, with salt and roasting due.[13]

In concluding his discussion of the various accounts of the cannibalism, historian Jay Rubenstein notes that the chroniclers clearly felt discomfort and tried to downplay what had happened, hence tending to give only part of the facts (but without agreeing on which part and interpretation to give).[14] He also notes that the fact that only Muslims were eaten is at odds with hunger as sole or primary motive – presumably, desperate starving people would not have cared much about the religion of those they consumed.[15] He concludes that the cannibalism at Ma‘arra likely went "beyond poor and hungry people eating from the dead" in secret, rather suggesting that "some of the soldiers must have recognized its potential utility [as a weapon of terror] and, hoping to drive the defenders into a quick surrender, made a spectacle of the eating, and made sure that Muslims were the only ones eaten."[14] He notes, however, that the Tafurs were almost certainly "scapegoats" blamed for acts which were by no means particularly limited to them.[16]

Historian Thomas Asbridge states that, while the "cannibalism at Marrat is among the most infamous of all the atrocities perpetrated by the First Crusaders", it nevertheless had "some positive effects on the crusaders' short-term prospects". Reports and rumours of their brutality in Ma‘arra and Antioch convinced "many Muslim commanders and garrisons that the crusaders were bloodthirsty barbarians, invincible savages who could not be resisted". Accordingly, many of them decided to "accept costly and humiliating truces with the Franks rather than face them in battle".[17]

Late medieval period

editIbn al-Muqaddam received lands in Maarat al-Nuʿman in 1179 as part of his compensation for yielding Baalbek to Saladin's brother Turan Shah. Ibn Jubayr passed by the town in 1185, and wrote that "Everywhere around the town are gardens... It is one of the most fertile and richest lands in the world".[3] Ibn Battuta visited in 1355, and described the town as small. The figs and pistachios of the town were exported to Damascus.[18]

Syrian Civil War

editThe town was the focus of intense protests against the government of President Bashar al-Assad on 2 June 2011. On 25 October 2011, clashes occurred between loyalists and defected soldiers at a roadblock on the edge of the town. The defectors launched an assault on the government held roadblock in retaliation for a raid on their positions the previous night.[19] The Free Syrian Army took control in December 2011–January 2012. The regime recaptured it at a later date. On 10 June 2012, the FSA took it back, but the military recaptured it in August.[20] Finally the FSA captured the town again in October after the Battle of Maarat al-Numan (2012).

As the Syrian Civil War followed, the town's strategic position on the road between Damascus and Aleppo made it a significant prize. Starting on 8 October 2012, the Battle of Maarat al-Numan (2012) was fought between the FSA and the government, causing numerous civilian casualties and severe material damage. The town was home to the FSA Division 13.[1]

A hospital in Maarrat al-Nu'man was struck by missiles on 15 February 2016.[21][22][23] The hospital was targeted again by Syrian government and Russian planes in April 2017,[24] on 19 September 2017[25] and in early January 2018.[26] On 19 April 2016, at least 37 people were reportedly killed when the Syrian government launched air strikes on markets. Dozens more were also injured during the attack.[27][28] In 2016, the town came under the control of HTS, but was also the site of significant civil society protests against HTS in 2016 and 2017.[1] The town's market was bombed in October 2017.[29] The Syrian Liberation Front took the town from HTS (Al-Qaeda) on 21 February 2018.[30]

The Ma'arrat al-Numan market bombing was perpetrated on 22 July 2019.[31][32][33] It killed 43 civilians, and injured another 109 people.[34]

On 28 January 2020, Ma'arrat al-Nu'man was successfully captured by government forces during the 5th Northwestern Syria offensive.[35]

On 30 November 2024 syrian rebel forces have retaken Maarat al-Numan, 5 years after the regime axis forces under Russia, Iran and Assad occupied it.

Landmarks

editToday the city has a museum with mosaics from the Dead Cities, a Friday mosque, a madrassa built by Abu al-Farawis in 1199, and remains of the medieval citadel. The city is the birthplace of the poet Al-Maʿarri (973–1057).

Climate

editMaarat al-Numan has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa).

| Climate data for Ma'arat al-Nu'man | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.8 (47.8) |

11.4 (52.5) |

16.1 (61.0) |

21.8 (71.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

35.1 (95.2) |

35.6 (96.1) |

31.8 (89.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.9 (40.8) |

6.7 (44.1) |

10.6 (51.1) |

15.1 (59.2) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.3 (77.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.3 (82.9) |

24.1 (75.4) |

18.9 (66.0) |

12.0 (53.6) |

7.3 (45.1) |

16.8 (62.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.0 (33.8) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

8.4 (47.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

17.8 (64.0) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.4 (61.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

6.0 (42.8) |

3.1 (37.6) |

10.6 (51.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 87 (3.4) |

73 (2.9) |

55 (2.2) |

34 (1.3) |

19 (0.7) |

6 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

5 (0.2) |

21 (0.8) |

35 (1.4) |

84 (3.3) |

419 (16.4) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[36] | |||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ a b c A Small Syrian Town’s Revolt Against Al-Qaida, News Deeply, 15 June 2017

- ^ a b c le Strange, 1890, p. 495

- ^ a b le Strange, 1890, p. 496

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 526, 537.

- ^ Bourget, Carine (2006). "The Rewriting of History in Amin Maalouf's The Crusades Through Arab Eyes". Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature. 30 (2, Article 3): 269. doi:10.4148/2334-4415.1633. Archived from the original on 19 July 2018.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 537.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 533, 535, 541.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 530–531.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 532–533.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 534–536.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 536.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, pp. 539–542.

- ^ Von Sybel, History and Literature of the Crusades; translated by Lady Duff Gordon.

- ^ a b Rubenstein 2008, p. 550.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 529.

- ^ Rubenstein 2008, p. 551.

- ^ Asbridge, Thomas (2004). The First Crusade: A New History. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 274–275. ISBN 978-0-19-517823-4.

- ^ le Strange, 1890, p. 497

- ^ "Assad forces fight deserters at northwestern town". Reuters. 25 October 2011. Archived from the original on February 1, 2016.

- ^ "Syria sends extra troops after rebels seize Idlib: NGO". English.ahram.org.eg. 2012-10-10.

- ^ SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg, Germany (15 February 2016). "Syrien: Ärzte-ohne-Grenzen-Krankenhaus bombardiert - ein gezielter Angriff?". SPIEGEL ONLINE. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Un hôpital de MSF en Syrie touché par des frappes aériennes". Radio-Canada.ca. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "MSF-backed hospital in Syria destroyed by air strikes: statement". Reuters. 2016-02-15. Retrieved 2016-02-15.

- ^ Diana Al Rifai Air strike destroys hospital in Idlib's Maaret al-Numan, Al-Jazeera, 3 Apr 2017

- ^ Kristin Helberg Fighting the jihadists with unusual weapons, Qantara, 06.01.2018

- ^ Syrian government defends Idlib campaign, condemns France, Reuters, 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Syria conflict: Air strikes on Idlib markets 'kill dozens'". BBC News. 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Air strike on market kills around 40 in opposition-held northwest Syria". Reuters. 19 April 2016.

- ^ AFP, At least 11 dead in Syria market air strike: Monitor, Middle East Eye, 9 October 2017

- ^ "Two of the largest factions in Syria's northwest merge, challenge HTS dominance". Syria Direct. 22 February 2018. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Chulov, Martin (23 July 2019). "Russia and Syria step up airstrikes against civilians in Idlib". Guardian. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "'Boundless criminality': Dozens killed in Idlib market bombing". Al Jazeera. 22 July 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "Syria war: Air strikes on town in rebel-held Idlib 'kill 31'". BBC News. 22 July 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2020.

- ^ "As children freeze to death in Syria, aid officials call for major cross-border delivery boost". UN News. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Middle East Eye

- ^ "Climate: Ma'arat al-Nu'man". Retrieved March 10, 2019.

Sources

edit- Amin Maalouf, The Crusades Through Arab Eyes. Schocken, 1989, ISBN 0-8052-0898-4

- le Strange, Guy (1890), Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500, Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund

- Rubenstein, Jay (2008). "Cannibals and Crusaders". French Historical Studies. 31 (4): 525–552. doi:10.1215/00161071-2008-005.