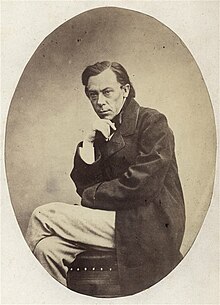

Ludwik Władysław Franciszek Kondratowicz (29 September 1823 – 15 September 1862), better known as Władysław Syrokomla (Lithuanian: Vladislovas Sirokomlė), was a Polish romantic poet, writer and translator working in Vilnius and Vilna Governorate, then Russian Empire, whose writings were mainly dedicated to the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In his writings, Syrokomla called himself a Lithuanian but was disappointed by his inability to speak the Lithuanian language.[1]

Władysław Syrokomla | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Ludwik Władysław Franciszek Kondratowicz 29 September 1823 Smolhava, Minsk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 15 September 1862 (aged 38) Vilnius, Vilna Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Resting place | Rasos Cemetery, Vilnius |

| Pen name | Władysław Syrokomla |

| Language | Polish and Belarusian |

| Genre | Romanticism |

| Signature | |

| |

Biography

editSyrokomla was born on 29 September 1823 in the village of Smolhava, in the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire (now Minsk Region, Belarus), to an impoverished noble family.[2][3][4][5] His parents were Aleksander Kajetan Kondratowicz (d. 1858) and Wiktoria (née Złotkowska).[6] His uncle was Hilary Kondratowicz (1790–1823), a Polish teacher of maths in Vilnius gymnasium, who published some articles in Wiadomości Brukowe.[6][7] A year after his birth his parents moved to another village called Jaskavičy.[5] In 1833 he entered the Dominican school in Nyasvizh.[5] He had to give up his studies due to financial problems. In 1837, he began work in a Marchačoŭščyna folwark.[5]

Between 1841 and 1844, he worked as a clerk in the Radziwiłł family land manager's office.[4][5] On 16 April 1844 in Nyasvizh he married Paulina Mitraszewska, with whom he had four children; three of them would die in the same year (1852).[5] Later, Syrokomla had a widely criticised an affair with a married actress Helena Kirkorowa.[8]

In 1844, he published the first of his poems – Pocztylion – under the pen-name Władysław Syrokomla, coined after his family's coat of arms.[4][5] The same year he also rented the small village of Załucze.[4] In 1853, after the death of three of his children, he sold it or gave his manor to his parents, and settled in Vilnius itself.[3][4][5] After a few months he rented the Bareikiškės village, near Vilnius.[5]

He became one of the editors (1861–1862) of the Kurier Wileński, the largest and most prestigious Polish-language daily newspaper published in the Vilnius region.[4] In 1858, he visited Kraków, and some time later he visited Warsaw.[3] For taking part in an anti-tsarist demonstration in 1861 in Warsaw he was arrested by the Okhrana and then sentenced to home arrest in his manor in Bareikiškės.[4][5] He died on 15 September 1862 and was buried in the Rasos Cemetery in Vilnius.[3][5]

Throughout his life, Syrokomla would remain impoverished; Czesław Miłosz wrote that he was "forever struggling against his lack of education and his poverty".[5][9] Despite that, Syrokomla had many influential and even wealthy friends; his manor was visited by count Eustachy Tyszkiewicz, Stanisław Moniuszko, Ignacy Chodźko, Mikołaj Malinowski, Antoni Pietkiewicz and others.[5]

Works

editSyrkomla was influenced by Adam Mickiewicz.[10] In his prose he supported the liberation of peasants and secession of the lands of former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth from Russian Empire, which had annexed portions of the Commonwealth, including what was the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, during its late 18th-century partitions.

Among the most notable of Syrokomla's works are translations of various Russian, French, Ukrainian, German and Latin poets, including works by Goethe, Heine, Lermontov, Shevchenko, Nekrasov, Béranger and others. His translations are considered a "great service" for the Polish language.[11] Syrokomla also produced a number of works about the rustic nature, people and customs of Lithuania and Belarus.[2][10]

The vast majority of his works were written in the Polish language, however, he also wrote several poems in Belarusian.[9] Syrokomla is considered by some as one of the early influential writers in modern Belarusian language, although many of his Belarusian poems are believed to be lost.[12]

Nevertheless, based on the knowledge of how the small nobility lived in Lithuania in the first half of the 19th century, it is assumed that Syrokomla was bilingual from childhood and was equally fluent in Belarusian and Polish.[citation needed] This is evidenced by the statements of the poet himself, which speak about the knowledge of the Belarusian language and how to master it in everyday contacts with the Belarusian people.[citation needed] He mentioned this in «Teka Wileńska»: "Karamzin, as a Russian, probably didn't know the old Belarusian dialect as we did, which we learned in everyday relations with the people".[13][14][15]

The poet was interested in the Belarusian language, introduced it into his works and mentioned it to the readers of the "Gazeta Warszawska". He wrote about the Belarusian language and its meaning in the past:[14][15]

This branch of the Slavic language is beautiful... and old! After all, this is the language of our Lithuanian Statute and legislation... it was spoken by three-quarters of ancient Lithuania, ordinary people, the gentry and the lords.

During his lifetime, his works were translated into several languages, including Lithuanian.[16] The composer Tchaikovsky adapted one of his works expressing a sympathetic view of the then-unliberated peasants – The Coral Beads – into a song.[17] He also wrote of the Tatar community in Lithuania and its mosques and of a Jewish bookseller in Vilnius.[18][19]

Some of his works are classified as gawęda (a story-like Polish epic literary genre).[9]

- Translations of Polish-Latin poets of Sigismund's age like Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski (Przekłady poetów polsko-łacińskich epoki zygmuntowskiej m.in. Macieja Kazimierza Sarbiewskiego)

- Chats and rhymes elusive (Gawędy i rymy ulotne) (1853)

- Born Jan Dęboróg (Urodzony Jan Dęboróg)

- Poetries of the last hour (Poezje ostatniej godziny)

- Liberation of peasants (Wyzwolenie włościan)

- Margiris. A poem from Lithuania's history (Margier. Poemat z dziejów Litwy) (1855)

- Good Thursday (Wielki Czwartek) (1856)

- Janko the Cemetery-man (Janko Cmentarnik) (1857)

- Kasper Kaliński (1858)

- A house in the forest (Chatka w lesie) (1855–1856)

- Hrabia na Wątorach (1856)

- The magnates and the orphan (Możnowładcy i sierota) (1859)

- Politicians from the countryside (Wiejscy politycy) (1858)

- Wojnarowski

- A journey of a familiar man through his familiar land (Podróż swojaka po swojszczyźnie)

- The history of literature in Poland (Dzieje literatury w Polsce)

Legacy

editWhile majority of sources refer to him as a "Polish poet", his legacy is best understood in the context of the multicultural Polish-Lithuanian identity.[20] His birthplace was located within the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania,[9] and he referred to himself as a Lithuanian when expressing his identity.[21]

In his book Wycieczki po Litwie w promieniach od Wilna ('Picnics from Vilnius throughout Lithuania') from 1857–1860, Syrokomla wrote the following:[1]

Another village near the manor is called Lelionys. On Sunday, a slightly more upbeat life buzzed in it. The inn could hear the noise of revelers. Girls and children were running in the street, shouting in Lithuanian. Unfortunately, the Lithuanian language is incomprehensible to us, who write historical poems of Lithuania. The Lithuanian villager turns out to be more civilized than us. In addition to his native Lithuanian language, he understands Polish well and explains it well.[1]

On the right, behind Airėnai, you can see the beautiful Geisiškės manor with a Gothic-style palace, which now belongs to the Giedraičiai dukes. This manor and the adjacent Europe or Eirope manor are former Jesuit properties. These two estates are separated by a beautiful lake with a small stream flowing out of it. Along it there is a dam covered with brambles and a mill. How I wanted to ask the villager something, but he did not understand me and answered with one word "Nesuprantu" [I don't understand]. I, a Lithuanian in the land of Lithuanians, couldn't talk to a Lithuanian![1]

Syrokomla also identified himself with the land of modern Belarus and its people.[22] During Syrokomla's burial ceremony, the Lithuanian poet Edvardas Jokūbas Daukša emphasized that while Syrokomla was influenced by Polish culture, he was a Lithuanian poet, closest to Lithuania after Adam Mickiewicz.[5][16] Teofil Lenartowicz wrote a memorial poem on his death referring to him as a "lirnik Litewski" (Lithuanian lyricist).[23] His works were often translated into Lithuanian and Belarusian languages.[24]

In modern Belarus, he is being praised for depicting the life of 19th century Belarus and for his ethnographic research of Belarusians.[25] In his publications, Syrokomla supported the Belarusian language and the Belarusian theatre plays by the playwright Vintsent Dunin-Martsinkyevich.[12][26]

In Belarus, there are streets named after W. Syrokomla (vulica Uladzislava Syrakomli) in Minsk, Grodno and in smaller towns Novogrudok, Nyasvizh, Pinsk, Vawkavysk, Maladzyechna and Pruzhany. In Smolhava a school is named after Syrokomla.[24]

In Warsaw's residential district Bródno (city district Warszawa-Targówek) there are two streets dedicated to the poet: Ludwik Kondratowicz St and Władysław Syrokomla St.

In Vilnius, a Polish-language school of the Polish minority in Lithuania is named after him.[24][27]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d "Iškylos iš Vilniaus po Lietuvą" (PDF). šaltiniai.info (in Lithuanian). pp. 32, 52.

- ^ a b Michael J. Mikoś (June 2002). Polish romantic literature: an anthology. Slavica. ISBN 978-0-89357-281-5. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Paul Soboleski (1881). Poets and poetry of Poland: a collection of Polish verse, including a short account of the history of Polish poetry, with sixty biographical sketches of Poland's poets and specimens of their composition. Knight & Leonard, printers. pp. 389–. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g (in Polish) Syrokomla Władysław, Encyklopedia WIEM

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n (in Polish) Irena Rusakiewicz, WILNIANIE ZASŁUŻENI DLA LITWY, POLSKI, EUROPY I ŚWIATA: Syrokomla Władysław (Ludwik Kondratowicz) (1823–1862). Litwa w twórczości Władysława Syrokomli

- ^ a b Kiśliak, Elżbieta. "Władysław Syrokomla". Polski Słownik Biograficzny. Vol. 46. Polska Akademia Nauk & Polska Akademia Umiejętności. p. 300.

- ^ Więsław Witold (2002). "Matematyka wileńska za czasów Adama Mickiewicza" (PDF). Roczniki Polskiego Towarzystwa Matematycznego. Seria II Wiadomości Matematyczne. 38: 165.

- ^ Noiński, Emil (2017). "Opiekunka dyktatora. Losy Heleny Kirkorowej (1828–1900) w Powstaniu Styczniowym i na zesłaniu syberyjskim". Studia z Historii Społeczno-Gospodarczej XIX i XX Wieku (in Polish). 17: 79. doi:10.18778/2080-8313.17.05. hdl:11089/25322. ISSN 2450-6796.

- ^ a b c d Czesław Miłosz (1983). The history of Polish literature. University of California Press. pp. 256–. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b William Fiddian Reddaway (1971). The Cambridge history of Poland. CUP Archive. pp. 332–. GGKEY:2G7C1LPZ3RN. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Paul Soboleski (1881). Poets and poetry of Poland: a collection of Polish verse, including a short account of the history of Polish poetry, with sixty biographical sketches of Poland's poets and specimens of their composition. Knight & Leonard, printers. pp. 388–. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b "Да 190-годдзя Уладзіслава Сыракомлі" [To the 190th anniversary of Uladzislau Syrakomla]. BelTA (in Belarusian). 2013-09-26. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ^ Księgarza i Typografa Wileńskiego Naukowego Okręgu — Teka Wilenska 1857 vol.1 S.205

- ^ a b Władysław syrokomla szkice i studia — Białystok, 2022. S.20

- ^ a b Karaś H. Język gawędy ludowej Wielki Czwartek Władysława Syrokomli na tle polszczyzny ogólnej i północnokresowej XIX wieku — Uniwersytet Warszawski, S.20

- ^ a b (in Lithuanian) Birutė LISAUSKAITĖ,"Vladislovas Sirokomlė (1823 – 1862 m.)". Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved October 16, 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) . 2007 - ^ Richard D. Sylvester (January 2004). Tchaikovsky's complete songs: a companion with texts and translations. Indiana University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-253-21676-2. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ Christoph Marcinkowski (2009). The Islamic world and the West: managing religious and cultural identities in the age of globalisation. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 100. ISBN 978-3-643-80001-5. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ Aleksander Hertz (1988). The Jews in Polish culture. Northwestern University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-8101-0758-8. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ^ Tomas Venclova (March 1999). Winter Dialogue. Northwestern University Press. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-0-8101-1726-6. Retrieved March 26, 2011.

- ^ Peter J. Potichnyj; Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies; McMaster University. Interdepartmental Committee on Communist and East European Affairs (1980). Poland and Ukraine, past and present. CIUS Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-920862-07-0. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- ^ Kauka, Alaksiej (2012-11-15). "Уладзіслаў Сыракомля: на сумежжы ліцвінства-беларускасці" [Uladzislau Syrakomla: on the border zone of Litvin and Belarusian]. Arche (in Belarusian). Dziejaslou. Retrieved 2016-09-16.

- ^ Narcyza Żmichowska (1894). Kwiaty rodzinne. Nakład G. Gebethnera i spółki. p. 249. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c Kiśliak, Elżbieta. "Władysław Syrokomla". Polski Słownik Biograficzny. Vol. 46. Polska Akademia Nauk & Polska Akademia Umiejętności. p. 307.

- ^

"Уладзіслаў Сыракомля" [Uladzislau Syrakomla, film by Belsat]. Mova Nanova (in Belarusian). Belsat. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

Адзін з першых сістэмных даследнікаў беларушчыны, Людвік Кандратовіч (Сыракомля) такімі ж беларускімі вачыма ўгледзеўся ў культуру свайго народу, як у шматвекавую духатворную традыцыю.

- ^

Marchiel, Uladzimir. ""Не забудуцца дум тваіх словы..." Уладзіслаў Сыракомля" [The words of your thoughts will not be forgotten... Uladzislau Syrakomla]. Official website of the Liuban rayon, Minsk voblasts (in Belarusian). Retrieved 2016-09-16.

Пра тое, што Сыракомля свядома ўскладаў на літаратуру і такую функцыю, сведчаць яго рэцэнзіі, у першую чаргу на беларускія творы Вінцэнта Дуніна-Марцінкевіча. Выступленне Сыракомлі ў польскай перыёдыцы з водгукамі на беларускамоўныя творы Дуніна-Марцінкевіча было ў поўнай згодзе з яго ідэалагічнай арыентацыяй, з рухам усёй яго творчасці насустрач дэмакратычнаму чытачу, насустрач селяніну і шарачковаму шляхціцу — галоўным адрасатам яго гутарак

- ^ (in Polish) O szkole > Historia, Szkoła średnia im. Władysława Syrokomli w Wilnie / Vilniaus Vladislavo Sirokomlės vidurinė mokykla

External links

editPolish Wikiquote has quotations related to: Władysław Syrokomla

- (in Polish) Patron szkoły (biography at the Vilnius High School dedicated to him)

- (in Polish) Irena Kardasz, Patron szkoły (biography at the Michałowo Elementary School dedicated to him, with a chronological table of his life)

- (in Polish) Józefa Drozdowska, Władysław Syrokomla (krótka bibliografia) (Short bio, also contains a list of further bibliographical sources)