Hugh Cholmondeley, 3rd Baron Delamere, KCMG (/ˈtʃʌmli/ CHUM-lee; 28 April 1870 – 13 November 1931), styled The Honourable from birth until 1887, was a British peer. He was one of the first and most influential British settlers in Kenya.

The Lord Delamere | |

|---|---|

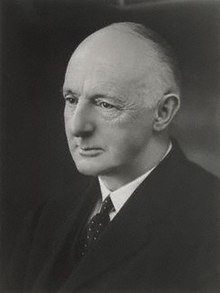

The 3rd Lord Delamere by Bassano, 26 September 1930. | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hon. Hugh Cholmondeley 28 April 1870 Vale Royal, Cheshire, England |

| Died | 12 November 1931 (aged 61) Loresho, Nairobi, Kenya |

| Spouses | |

| Children | Thomas Cholmondeley, 4th Baron Delamere |

| Parents |

|

| Education | Eton College |

| Occupation | Farmer, politician |

Lord Delamere was the son of Hugh Cholmondeley, 2nd Baron Delamere, and his second wife, Augusta Emily Seymour, daughter of Sir George Hamilton Seymour.

Lord Delamere moved to Kenya in 1901 and acquired vast land holdings from the British Crown. Over the years, he became the unofficial 'leader' of the colony's European community. He was as famous for his tireless labours to establish a working agricultural economy in East Africa as he was for childish antics among his European friends when he was at his leisure.

Early years

editDelamere left Eton at the age of sixteen with the intention of entering the British Army,[1] but gave up his military pursuits after acceding to the title aged seventeen on the death of his father on 1 August 1887.

Baron Delamere was an indirect descendant of Sir Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Great Britain.[2]

He served in the 3rd Battalion of the Cheshire Regiment, a part-time militia battalion, as a lieutenant.[3] He later transferred to the Cheshire Yeomanry (Earl of Chester's), and was promoted to captain on 8 April 1893.[4] On 27 February 1895, he resigned his commission.[5]

The young baron inherited a sizeable estate in the North of England, including land that had been in the Cholmondeley family since 1615:[6] 7,000 acres (28 km2) and the ancestral seat at Vale Royal in the county of Cheshire.[7]

African expeditionary explorer

editSomaliland

editThe young Lord Delamere made his first trip to Africa in 1891 to hunt lion in British Somaliland, and returned yearly to resume the hunt.

In 1893 he would meet the warrior and poet Hussein Hasan who accompanied him on his 1893 hunting expedition. On the expedition a lioness nearly killed Hussein and his famous horse Mangalool in a pursuit they narrowly escaped.[8]

In 1894 Lord Delamere was severely mauled by an attacking lion, and was only saved when his Somali gunbearer, Abdullah Ashur, leaped on the lion, giving Delamere time to retrieve his rifle. As a result of the attack, Lord Delamere limped for the rest of his life; he also developed a healthy respect for Somalis.[9]

It is believed that on one of these Somaliland hunting trips, Delamere coined the term 'white hunter', the term which came to describe the white safari hunter in colonial East Africa. Delamere employed a professional hunter named Alan Black and a native Somali hunter to lead the safari. As the story goes, to avoid confusion, the Somali was referred to as the 'black hunter', and Black was called the 'white hunter'.[10]

On an expedition in 1896, Delamere, with a retinue including a doctor, taxidermist, photographer, and 200 camels, set out to cross the deserts of southern Somaliland, intending to enter British East Africa from the north. In 1897, he arrived in the lush green highlands of what is now central Kenya.[9]

Colonial Kenya

editIn 1899, the young Lord Delamere married Lady Florence Anne Cole, an Anglo-Irish aristocrat from a prominent Ulster family. She was the daughter of The 4th Earl of Enniskillen, a peer whose ancestral seat was Florence Court in south-west County Fermanagh in the north of Ireland.[11] The couple soon sought to relocate to what became known as 'the White Highlands' in Kenya.

Lord Delamere originally applied for a land grant from the British Crown in May 1903, but was denied because the Governor of the Protectorate, Sir Charles Eliot, thought the land was too far from any population centre.[12] His next request for 100,000 acres (400 km2), near what is now Naivasha, was denied because the government felt that settlement by a colonising farmer might ignite conflicts with the Maasai tribesman who lived on the land. Delamere's third attempt at land acquisition was successful. He received a 99-year lease on 100,000 acres (400 km2) of land that would be named 'Equator Ranch', requiring him to pay a £200 annual rent and to spend £5,000 on the land over the first five years of occupancy.[12] In 1906, he acquired a large farm in Gilgil division, which would eventually include more than 50,000 acres (210 km2), located between Elementeita Railway Station, Elmenteita Badlands and Mbaruk Railway Station. This ranch he named Soysambu.[9] Together, these vast possessions made Delamere one of Kenya's 'largemen'; the local name for the handful of colonists with the greatest land holdings.

Farming

editAmong Kenya's white settlers, Lord Delamere was famous for his utter devotion to developing Kenyan agriculture. For many years his only homes in Kenya were native-style mud and grass huts, which his wife (who was Ulster Anglo-Irish) decorated with their fine English and Irish furnishings.[13] For twenty years, Delamere farmed his colossal land by trial, error and dogged effort, experimenting endlessly with crops and livestock, and accruing an invaluable stockpile of knowledge that would later serve as the foundation for the agricultural economy of the colony.[14]

By 1905, Delamere was a pioneer of the East African dairy industry. He was also a pioneer at crossbreeding animals, beginning with sheep and chicken, then moving to cattle; most of his imported animals, however, succumbed to diseases such as foot and mouth and red water disease.[15] Delamere purchased Ryeland Rams from England to mate with 11,000 Maasai ewes, and in 1904, imported 500 pure-bred merino ewes from New Zealand. Four-fifths of the merino ewes quickly died, and the remaining stock were moved to Delamere's Soysambu Ranch, as well as the remaining stock of 1,500 imported cattle that suffered from pleuro-pneumonia.[16]

Eventually, Lord Delamere decided to grow wheat. This, too, was plagued by disease, specifically rust (fungus).[17] By 1909, Delamere was out of money, resting his last hopes on a 1,200-acre (4.9 km2) wheat crop that eventually failed.[14] He was quoted by author Elspeth Huxley as commenting drily, 'I started to grow wheat in East Africa to prove that though I lived on the equator, I was not in an equatorial country.' Delamere eventually created a 'wheat laboratory' on his farm, employing scientists to manufacture hardy wheat varieties for the Kenyan highlands.[18] To supplement his income, he even tried raising ostriches for their feathers, importing incubators from Europe; this venture also failed with the advent of the motor car and the decline in fashion of feathered hats.[19] Delamere was the first European to start a maize farm, Florida Farm, in the Rongai Valley, and established the first flour mill in Kenya.[20] By 1914, his efforts finally began to generate a profit.[21] In the same year, his wife Florence died from heart-failure.[22]

Happy Valley set

editLord Delamere was active in recruiting settlers to East Africa, promising new colonists 640 acres (2.6 km2), with 200 people eventually responding.[23] He persuaded some of his friends among the British landed gentry to buy large estates like his own and take up life in Kenya; he is credited with helping to found the so-called Happy Valley set, a clique of well-off British colonials whose pleasure-seeking habits eventually took the form of drug-taking and wife-swapping. The story is often told of Delamere riding his horse into the dining room of Nairobi's Norfolk Hotel and jumping over the tables.[citation needed] He was also known to knock golf balls onto the roof of the Muthaiga Country Club, the pink stucco gathering-place for Nairobi's white elite, and then climb up to retrieve them.[24]

At the outbreak of World War I, Delamere was placed in charge of intelligence on the Maasai border, monitoring the movements of German units in German East Africa.[25] Delamere entertained many high-ranking official visitors to Kenya, including then Under-Secretary for the Colonies, Winston Churchill. He was also the first president of the East African Turf Club.[26]

Government

editDelamere embodied the many contradictions of the committed East African settler. He was personally fond of many Africans, and particularly enjoyed the company of the Maasai (even gently tolerating their habit of pilfering his cattle for their own herds),[27] but fought fiercely to maintain white supremacy in the colony. Writing in 1927, Delamere claimed that the "extension of European civilization was in itself a desirable thing", and white people were "superior to heterogeneous African races only now emerging from centuries of relative barbarism... the opening up of new areas by means of genuine colonisation was to the advantage to the world."[28] Richard Meinertzhagen (himself a complex figure of Africa's colonial days) quoted Delamere as proclaiming, "I am going to prove to you all that this is a white man's country".[29]

These views held great sway among the settlers because Delamere was their undisputed, if unofficial, leader and, in some measure, spokesman for 30 years.[citation needed] He was a member of the Legislative Council, the Executive Council, and, in 1907, became President of the Colonists' Association.[30] In 1921 he established the Reform Party. Errol Trzebinski, who wrote a number of books on Kenya's colonial elite, wrote of him: "Delamere was the Rhodes of Kenya and the settlers followed him both politically and spiritually".[31] Another contemporary and former colonist said more or less the same: “(His) ascendancy over the settlers of Kenya has been enjoyed long enough for him to expect all men – and women – to do his bidding, and do it promptly. He is their Moses. For 25 years he has been their guide".[32]

Beryl Markham, the aviator and author, was close with Delamere and his wife, who served for a few years as Markham's surrogate mother. She summed Delamere up thus: "Delamere had two great loves – East Africa and the Masai People.... Delamere's character had as many facets as cut stone, but each facet shone with individual brightness. His generosity is legendary, but so is his sometimes wholly unjustified anger.... To him nothing was more important than the agricultural and political future of British East Africa – and so, he was a serious man. Yet his gaiety and occasional abandonment to the spirit of fun, which I have often witnessed, could hardly be equalled except by an ebullient schoolboy."[33]

Delamere's efforts to steer Kenyan economic and racial policy, which often contravened the more pro-African intentions of the Colonial Office, were assisted by his powerful friends at home in Great Britain. Delamere, and other settlers, were so successful in affecting Kenya's politics that, in 1923, the British government responded with the Devonshire White Paper, which declared officially that, in Kenya, the concerns of Africans were 'paramount', even when they conflicted with the needs of whites.[34]

Legacy

editLord Delamere died in November 1931, at age 61.[35] He was survived by his second wife, formerly Gwladys, Lady Markham (née Gwladys Helen Beckett, daughter of Hon. Rupert Eveleyn Beckett).[36] His widow, Gwladys, became the second female Mayor of Nairobi. She was portrayed by actress Susan Fleetwood in the 1941-set film White Mischief (1987) as "Gwladys Delamere", one of Lord Erroll's Happy Valley friends.

He was succeeded in the barony by his son from his first marriage, Thomas.[11] At his death, he left Kenya's agricultural economy healthy enough to develop into one of the most stable economies in Africa. He also left unpaid bank loans totalling £500,000.[17]

Nairobi's Sixth Avenue was named Delamere Avenue to commemorate his place in the development of the colony, and an eight-foot bronze statue of the 3rd Baron was erected at the street's head, across from the New Stanley Hotel.

When Kenya achieved independence in 1963, many white settlers opted to sell their farms and leave the country rather than submit to African rule. Delamere's family, by then headed by his son Thomas, the 4th Baron, elected to remain and accept Kenyan citizenship. Other traces of Delamere's colonial "reign" were not permitted to linger. Delamere Avenue was renamed as Kenyatta Avenue, after Kenya's first president, Jomo Kenyatta, and the statue of Delamere was relocated to the family's Soysambu estate, where it faces out toward the mountain known locally as "Delamere's Nose" or "The Sleeping Warrior." Among the Maasai, with whom Delamere was the first to establish a strong European connection, his family is now frequently reviled as those who "stole" the Maasai's land;[37] but at his death, The Times reported that this complicated man had been amongst the very few Europeans who had made it a point to learn the Maasai language.[11]

One of the restaurants inside the Nairobi Norfolk Hotel has been known as the Lord Delamere Terrace for decades.[38]

Cholmondeley is a character in Karen Blixen's Out of Africa and is played by Michael Gough in the 1985 adaptation.

Selected works

edit- 1926 – Kenya. Correspondence with the government of Kenya relating to Lord Delamere's acquisition of land in Kenya ... London: H.M. Stationery Office. OCLC 12325519

- 1927 – Kenya elections : Lord Delamere's speech to his constituents. Nairobi: reprinted from the East African standard (January 1927). OCLC 85028232

Notes

edit- ^ Best, Nicholas, (1979). Happy Valley: The Story of the English in Kenya, p.39.

- ^ Hayden, Joseph. (1851). The book of dignities, pp. 527, 565.

- ^ "Page 4246 | Issue 26190, 7 August 1891 | London Gazette | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Page 2123 | Issue 26390, 7 April 1893 | London Gazette | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ "Page 1152 | Issue 26602, 26 February 1895 | London Gazette | The Gazette". www.thegazette.co.uk. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Pakenham, Compton. [1] "Kenya as a White Man's Country; The Story of Lord Delamere and a Colony That Has Peculiarly Interesting Racial and Social Problems,"] The New York Times. 7 July 1935. (subscription required)

- ^ "Lady Delamere Dies in Africa," The New York Times. 19 May 1914;Holland, G.D et al. (1977). Vale Royal Abbey and House, pp. 20–32; Westair-Reproductions: Cheshire, Museum finder Archived 7 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lord Delamere (1896). The Badminton Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Volume 2:Lion Shooting. Longmans, Green, and Company. pp. 597–607.

- ^ a b c Bull, Bartle (1992). Safari: A Chronicle of Adventure, p.188.

- ^ Brian Herne, White Hunters: The Golden Age of Safaris, Henry Holt & Co., 1999, pages 6–7

- ^ a b c "Lord Delamere: Pioneer and Leader in Kenya,"[dead link] The Times (London). 14 November 1931.

- ^ a b Best, Happy Valley, p. 41

- ^ Bull, Safari, p. 191

- ^ a b Best, Happy Valley, p. 43

- ^ Kamau, John, Who was Lord Delamere?, The East African Standard, 22 May 2005, available at http://www.eastandard.net/archives/cl/hm_news/news.php?articleid=21034 Archived 18 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Huxley, Elspeth, Settlers of Kenya (1975), pp. 29–30

- ^ a b Kamau, John, Who was Lord Delamere?

- ^ Huxley, Settlers of Kenya, pp. 25–27

- ^ Best, Happy Valley, p. 45

- ^ Church, Archibald, East Africa: A New Dominion, 1970, pp. 287–8

- ^ Huxley, Settlers of Kenya p. 30

- ^ "DELAMERE, Florence Anne, Lady". Europeans In East Africa. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

- ^ Hughes, Anthony John, East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Penguin, 1969, p. 275

- ^ Thurman, Judith, Isak Dinesen: Life of a Storyteller, MacMillan, 1999, p. 123

- ^ Herne, Brian, White Hunters: The Golden Age of African Safaris, 1999, pp. 99

- ^ Herne, White Hunters, pp. 21–33

- ^ Bull, Safari, pp. 189–191

- ^ Thurman, Judith, Isak Dinesen: The Life of a Storyteller, MacMillan, 1999, p. 180

- ^ Meinertzhagen from African Diary, quoted in Ridgeway, Rick, The Shadow of Kilimanjaro, Owl Publishing Company, 1998, p. 194

- ^ Trzebinski, Errol, The Kenya Pioneers, W.W. Norton 1986, p. 129 and Berman, Bruce, Control & Crisis in Colonial Kenya: The Dialectic of Domination, James Currey 1990, p. 140

- ^ Trzebinski, The Kenya Pioneers, p. 23

- ^ Hughes, East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, p. 275

- ^ Markham, Beryl, West with the Night, North Point Press, San Francisco, 1983, pp. 71–72

- ^ Maxon, Robert, Struggle for Kenya: The Loss and Reassertion of Imperial Initiative, 1912–1923, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1993, pp. 13–14

- ^ "Lord Delamere Dies on his African Ranch; Leader in Development of Kenya Colony—Was Pioneer in Big Game Hunting Expeditions," The New York Times. 14 November 1931. (subscription required)

- ^ "Gwladys Lady Delamere" (obituary). The New York Times. 23 February 1943 (subscription required)

- ^ Barton, The Curse of White Mischief

- ^ "Traveling in Style : Our Hearts Are in the Highlands", David Lamb, LA Times, 20 March 1988.

References

edit- Debrett, John, Charles Kidd, David Williamson. (1990). Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage.[permanent dead link] New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-38847-1

- Hayden, Joseph. (1851). The book of dignities: containing rolls of the official personages of the British Empire. London: Longmans, Brown, Green, and Longmans. OCLC 2359133

- Holland, G.D et al. (1977). Vale Royal Abbey and House. Winsford, Cheshire: Winsford Local History Society. OCLC 27001031

- Hopkirk, Mary. (1991). Life at Vale Royal Great House 1907–1925: The Memoirs of Mary Hopkirk (Née Dempster). Northwich & District Heritage Soc, OCLC 41926624

- Huxley, Elspeth Joscelin Grant. (1935). White Man's Country: Lord Delamere and the Making of Kenya. London: Macmillan. OCLC 4585821