Richard Samuel Attenborough, Baron Attenborough (/ˈætənbərə/; 29 August 1923 – 24 August 2014) was an English actor, film director, and producer.

The Lord Attenborough | |

|---|---|

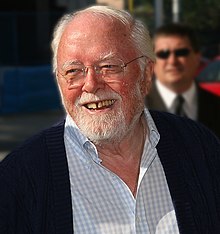

Attenborough at the 2007 Toronto International Film Festival | |

| Born | Richard Samuel Attenborough 29 August 1923 Cambridge, England |

| Died | 24 August 2014 (aged 90) Northwood, London, England |

| Resting place | St Mary Magdalene, Richmond, London |

| Occupations |

|

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Father | Frederick Attenborough |

| Relatives |

|

| Member of the House of Lords | |

| Life peerage 30 July 1993 – 24 August 2014 | |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service | Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1940–1945 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | Film Production Unit |

| Battles / wars | Second World War |

Attenborough was the president of the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) and the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA), as well as life president of the Premier League club Chelsea. He joined the Royal Air Force during World War II and served in the film unit, going on several bombing raids over continental Europe and filming the conflict from the rear gunner's position. He was the older brother of broadcaster and nature presenter Sir David Attenborough and motor executive John Attenborough. He was married to actress Sheila Sim from 1945 until his death.

As an actor, Attenborough is best remembered for his film roles in Brighton Rock (1948), I'm All Right Jack (1959), The Great Escape (1963), Seance on a Wet Afternoon (1964), The Sand Pebbles (1966), Doctor Dolittle (1967), 10 Rillington Place (1971), Jurassic Park (1993) and Miracle on 34th Street (1994). In 1952, he has appeared on the West End stage, originating the role of Detective Sergeant Trotter in Agatha Christie's The Mousetrap which has since become the world's longest-running play.[1]

For his directorial debut in 1969's Oh! What a Lovely War, Attenborough was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Direction; later, he would be additionally nominated for his films Young Winston (1972), A Bridge Too Far (1977) and Cry Freedom (1987). For the film Gandhi, in 1983, he won two Academy Awards, Best Picture and Best Director. The British Film Institute ranked Gandhi the 34th greatest British film of the 20th century. Attenborough has also won four BAFTA Awards, four Golden Globe Awards, and the 1983 BAFTA Fellowship for lifetime achievement.

Early life

editAttenborough was born on 29 August 1923[2] in Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, the eldest son of three from mother Mary Attenborough (née Clegg)—a founding member of the Marriage Guidance Council—and father Frederick Levi Attenborough, a scholar and academic administrator who was a fellow at Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and wrote a standard text on Anglo-Saxon law.[3] Attenborough was educated at Wyggeston Grammar School for Boys in Leicester and studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA).[4]

In September 1939, while father Frederick Attenborough was Principal of University College, Leicester (1932–1951), the Attenboroughs took-in two German Jewish refugee girls, Helga and Irene Bejach (aged 9 and 11, respectively), with the girls living with them in College House and being adopted by the family after the war, when it was discovered that their parents had been killed.[5] The sisters moved to the United States in the 1950s and lived with an uncle, where they married and achieved American citizenship; Irene died in 1992, and Helga, in 2005.[6]

During the Second World War, Attenborough served in the Royal Air Force. After initial pilot training, he was seconded to the newly-formed Royal Air Force Film Production Unit at Pinewood Studios, under the command of Flight Lieutenant John Boulting (whose brother, Peter Cotes, later directed Attenborough in the play The Mousetrap), where he appeared with Edward G. Robinson in the propaganda film Journey Together (1945). He then volunteered to fly with the film production unit; after further training, he sustained permanent ear damage. After being qualified as a sergeant, he flew on several operations over Europe, filming from the tail gunner's position to document the outcome of RAF Bomber Command sorties.[7]

Acting career

editAttenborough's acting career started on the theatre stage, where he appeared in shows at Leicester's Little Theatre, Dover Street, prior to his attending RADA, where he remained Patron until his death. Attenborough's first major, credited role was portraying Tommy Draper in Brian Desmond Hurst's The Hundred Pound Window (1944), a role in which the character helps to rescue his accountant father who has taken a wrong turn in life. Attenborough's film career had begun by 1942, in an uncredited role as a sailor deserting his post under fire in the Noël Coward/David Lean production In Which We Serve (his name and character were omitted from the original release-print credits), a role that helped typecast him for many years as a spiv in films like London Belongs to Me (1948), Morning Departure (1950) and his breakthrough role as Pinkie Brown in John Boulting's film adaptation of Graham Greene's novel Brighton Rock (1947), a role that he had previously played to great acclaim at the Garrick Theatre in 1943. He played the lead at age 22 as an RAF cadet pilot in Journey Together (1945), in which top-billed Edward G. Robinson played his instructor.

In 1949, exhibitors voted him the sixth most popular British actor at the box office.[8]

Early in his stage career, Attenborough starred in the West End production of Agatha Christie's The Mousetrap, which went on to become the world's longest running stage production. Both he and his wife were among the original cast members of the production, which opened in 1952 at the Ambassadors Theatre, moving to St Martin's Theatre in 1974; the production ran continuously for nearly seven decades, until it was shut down by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The Attenboroughs took a 10 per cent profit-participation in the production, which was paid for out of their combined weekly salary; Attenborough later wrote in his autobiography, "It proved to be the wisest business decision I've ever made... but foolishly I sold some of my share to open a short-lived Mayfair restaurant called 'The Little Elephant' and later still, disposed of the remainder in order to keep Gandhi afloat."[9]

At the beginning of the 1950s Attenborough featured on radio on the BBC Light Programme introducing records.[10]

Attenborough worked prolifically in British films for the next 30 years, including in the 1950s, appearing in several successful comedies for John and Roy Boulting, such as Private's Progress (1956) and I'm All Right Jack (1959).[11]

In 1963, he appeared alongside Steve McQueen and James Garner in The Great Escape as RAF Squadron Leader Roger Bartlett ("Big X"), the head of the escape committee, based on the real-life exploits of Roger Bushell. It was his first appearance in a major Hollywood film blockbuster and his most successful film thus far.[11] During the 1960s, he expanded his range of character roles in films such as Séance on a Wet Afternoon (1964) and Guns at Batasi (1964), for which he won the BAFTA Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Regimental Sergeant Major Lauderdale. In 1965 he played Lew Moran opposite James Stewart in The Flight of the Phoenix. In 1967 and 1968, he won back-to-back Golden Globe Awards in the category of Best Supporting Actor, the first time for The Sand Pebbles, again co-starring Steve McQueen, and the second time for Doctor Dolittle starring Rex Harrison.[11]

His portrayal of the serial killer John Christie in 10 Rillington Place (1971) garnered excellent reviews. In 1977, he played the ruthless General Outram, again to great acclaim, in the Indian director Satyajit Ray's period piece The Chess Players.[11]

He took no acting roles following his appearance in Otto Preminger's version of The Human Factor (1979) until his appearance as John Hammond in Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park (1993) and the film's sequel, The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997). He starred in the remake of Miracle on 34th Street (1994) as Kris Kringle. Later he made occasional appearances in supporting roles, including as Sir William Cecil in the historical drama Elizabeth (1998), Jacob in Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and as "The Narrator" in the film adaptation of Spike Milligan's comedy book Puckoon (2002).[12] He played the 'Old Gentleman' in the rear carriage of the train in the TV movie "The Railway Children" made in 2000.

He made his only appearance in a film adaptation of Shakespeare when he played the English ambassador who announces that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead at the end of Kenneth Branagh's Hamlet (1996).[11]

Producer and director

editIn the late 1950s, Attenborough formed a production company, Beaver Films, with Bryan Forbes and began to build a profile as a producer on projects including The League of Gentlemen (1959), The Angry Silence (1960) and Whistle Down the Wind (1961), appearing in the cast of the first two films.[11] His performance in The Angry Silence earned him his first nomination for a BAFTA. Séance on a Wet Afternoon won him his first BAFTA award.

His feature film directorial debut was the all-star screen version of the hit musical Oh! What a Lovely War (1969), after which his acting appearances became sporadic as he concentrated more on directing and producing. He later directed two epic period films: Young Winston (1972), based on the early life of Winston Churchill, and A Bridge Too Far (1977), an all-star account of Second World War Operation Market Garden.[11]

He won the 1982 Academy Award for Best Director for his historical epic Gandhi, and as the film's producer, the Academy Award for Best Picture; the same film garnered two Golden Globes, this time for Best Director and Best Foreign Film, in 1983. He had been attempting to get the project made for 18 years.[11] He directed the screen version of the musical A Chorus Line (1985) and the anti-apartheid drama Cry Freedom (1987). He was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Director for both films.[11] The success of the latter film prompted Attenborough to sign a contract with Universal Pictures to produce and direct films over the next five years, set to produce three films for the studio, and timetable calls would be set up by January and the first production was slated for release by 1989.[13]

His later films as director and producer include Chaplin (1992) starring Robert Downey Jr., as Charlie Chaplin and Shadowlands (1993), based on the relationship between C. S. Lewis and Joy Gresham (C. S. Lewis was portrayed by Anthony Hopkins, who had appeared in four previous films for Attenborough: Young Winston, A Bridge Too Far, Magic and Chaplin).

Between 2006 and 2007, he spent time in Belfast, working on his last film as director and producer, Closing the Ring, a love story set in Belfast during the Second World War, and starring Shirley MacLaine, Christopher Plummer and Pete Postlethwaite.[14]

Despite maintaining an acting career alongside his directorial roles, Attenborough never directed himself (save for an uncredited cameo appearance in A Bridge Too Far).[15]

Later projects

editAfter 33 years of dedicated service as President of the Muscular Dystrophy campaign, Attenborough became the charity's Honorary Life President in 2004. In 2012, the charity, which leads the fight against muscle-wasting conditions in the UK, established the Richard Attenborough Fellowship Fund to honour his lifelong commitment to the charity, and to ensure the future of clinical research and training at leading UK neuromuscular centres.[16]

Attenborough was also the patron of the United World Colleges movement, whereby he contributed to the colleges that are part of the organisation. He was a frequent visitor to the Waterford Kamhlaba United World College of Southern Africa (UWCSA). With his wife, they founded the Richard and Sheila Attenborough Visual Arts Centre. He founded the Jane Holland Creative Centre for Learning at Waterford Kamhlaba in Swaziland in memory of his daughter who died in the tsunami on 26 December 2004.[17]

He was a longtime advocate of education that does not judge upon colour, race, creed or religion. His attachment to Waterford was his passion for non-racial education, which were the grounds on which Waterford Kamhlaba was founded. Waterford was one of his inspirations for directing the film Cry Freedom, based on the life of Steve Biko.[17][18][citation needed]

Attenborough served as Chair of the British Film Institute between 1981 and 1992.[19]

He founded The Richard Attenborough Arts Centre on the Leicester University campus in 1997, specifically designed to provide access for the disabled, in particular as practitioners.[20][21][citation needed]

He was elected to the post of Chancellor of the University of Sussex on 20 March 1998, replacing The Duke of Richmond and Gordon. He stood down as Chancellor of the university following graduation in July 2008.[22]

A lifelong supporter of Chelsea Football Club, Attenborough served as a director of the club from 1969 to 1982 and between 1993 and 2008 held the honorary position of Life Vice President. On 30 November 2008 he was honoured with the title of Life President at the club's stadium, Stamford Bridge.

He was also head of the consortium Dragon International Film Studios, which was constructing a film and television studio complex in Llanilid, Wales, nicknamed "Valleywood". In March 2008, the project was placed into administration with debts of £15 million and was considered for sale of the assets in 2011.[23] A mooted long-term lease to Fox 21 fell through in 2015, though the facilities continue to be used for filmmaking.[24]

He had a lifelong ambition to make a film about his hero the political theorist and revolutionary Thomas Paine, whom he called "one of the finest men that ever lived". He said in an interview in 2006 that "I could understand him. He wrote in simple English. I found all his aspirations – the rights of women, the health service, universal education... Everything you can think of that we want is in Rights of Man or The Age of Reason or Common Sense."[25][26][27] He could not secure the funding to do so.[28] The website "A Gift for Dickie" was launched by two filmmakers from Luton in June 2008 with the aim of raising £40m in 400 days to help him make the film, but the target was not met and the money that had been raised was refunded.[29][30]

Personal life

editAttenborough's father was the principal of University College, Leicester, now the city's university. This resulted in a long association with the university, with Attenborough becoming a patron. The university's Embrace Arts at the RA centre,[31] which opened in 1997 is named in his honour. He had two younger brothers: naturalist and broadcaster David and motor trade executive John.

Attenborough married actress Sheila Sim in Kensington on 22 January 1945.[32][33] From 1949 until October 2012, they lived in Old Friars on Richmond Green in London.

In the 1940s, he was asked to 'improve his physical condition' for his role as Pinkie in Brighton Rock. He trained with Chelsea Football Club for a fortnight, subsequently becoming good friends with those at the club. He went on to become a director during the 1970s, helping to prevent the club losing its home ground by holding onto his club shares and donating them, worth over £950,000, to Chelsea. In 2008, Attenborough was appointed Life President of Chelsea Football Club.[34]

On 26 December 2004, the couple's elder daughter, Jane Holland (30 September 1955 – 26 December 2004), along with her mother-in-law, Audrey Holland, and Attenborough's 15-year-old granddaughter, Lucy, were killed when a tsunami caused by the Indian Ocean earthquake struck Khao Lak, Thailand, where they were on holiday.[35][36][37]

A service was held on 8 March 2005 and Attenborough read a lesson at the national memorial service on 11 May 2005. His grandson Samuel Holland, who survived the tsunami uninjured, and granddaughter Alice Holland, who suffered severe leg injuries, also read in the service.[37] A commemorative plaque was placed in the floor of St Mary Magdalene's parish church in Richmond. Attenborough later described the Boxing Day of 2004 as "the worst day of my life". Attenborough had two other children, Michael (born 13 February 1950) and Charlotte (born 29 June 1959). Michael is a theatre director formerly the Deputy Artistic Director of the RSC and artistic director of the Almeida Theatre in London and has been married to actress Karen Lewis since 1984; they have two sons, Tom and Will. Charlotte, an actress, married Graham Sinclair in 1993 and has two children.[35]

At the 1983 United Kingdom general election Attenborough supported the Social Democratic Party.[38] He publicly endorsed the Labour Party in the 2005 general election, despite his opposition to the Iraq War.[39]

Attenborough collected Picasso ceramics from the 1950s. More than 100 items went on display at the New Walk Museum and Art Gallery in Leicester in 2007, in an exhibition dedicated to family members lost in the tsunami.[40]

In 2008, he published an informal autobiography entitled Entirely Up to You, Darling in association with his colleague Diana Hawkins.[41][42]

Health and death

editIn August 2008, Attenborough entered hospital with heart problems and was fitted with a pacemaker. In December 2008, he suffered a fall at his home after a stroke[43] and was admitted to St George's Hospital, Tooting, South West London. In November 2009, Attenborough, in what he called a "house clearance" sale, sold part of his extensive art collection, which included works by L. S. Lowry, C. R. W. Nevinson and Graham Sutherland, generating £4.6 million at Sotheby's.[44]

In January 2011, he sold his Rhubodach estate on the Scottish Isle of Bute for £1.48 million.[45] In May 2011, David Attenborough said his brother had been confined to a wheelchair since his stroke in 2008,[43] but was still capable of holding a conversation. He added that "he won't be making any more films."[46]

In June 2012, shortly before her 90th birthday, Sheila Sim entered the professional actors' retirement home Denville Hall, in Northwood, London, for which she and Attenborough had helped raise funds. In October 2012, it was announced that Attenborough was putting the family home, Old Friars, with its attached offices, Beaver Lodge, which came complete with a sound-proofed cinema in the garden, on the market for £11.5 million. His brother David stated: "He and his wife both loved the house, but they now need full-time care.[47] It simply isn't practical to keep the house on any more."[48] In December 2012, in light of his deteriorating health, Attenborough moved into the same nursing home in London to be with his wife, as confirmed by their son Michael.[43]

Attenborough died at Denville Hall, on 24 August 2014, five days before his 91st birthday.[49][50] He requested that his ashes be interred in a vault at St Mary Magdalene church in Richmond beside those of his daughter, Jane, and his granddaughter, Lucy, both of whom had died in the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami.[51][52] He was survived by Sheila, his wife of 69 years, their oldest and youngest children, six grandchildren, two great-grandchildren, and his younger brother David. Sheila died on 19 January 2016.

Honours

editIn the 1967 Birthday Honours, Attenborough was appointed a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE).[53] He was made a Knight Bachelor in the 1976 New Year Honours,[54] having the honour conferred on 10 February 1976.[55]

Attenborough was the subject of This Is Your Life in December 1962 when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at the Savoy Hotel, during a dinner held to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the Agatha Christie play The Mousetrap, in which he had been an original cast member.[11]

In 1983, Attenborough was awarded the Padma Bhushan, India's third highest civilian award,[56] and the Martin Luther King Jr. Nonviolence Peace Prize by the Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change.[57] He was also awarded France's most distinguished awards, the Legion of Honour and the Order of Arts and Letters[58] and the Order of the Companions of O.R. Tambo by the South African government 'for his contribution to the struggle against apartheid'.

In 1992, the Hamburg-based Alfred Toepfer Foundation awarded Attenborough its annual Shakespeare Prize in recognition of his life's work. The following year he was appointed a Fellow of King's College London.[59]

On 30 July 1993, he was created a life peer as Baron Attenborough, of Richmond upon Thames in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames.[60][61] Although the appointment by John Major was 'non-political' (it was granted for services to the cinema) and he could have been a crossbencher, Attenborough chose to take the Labour whip and so sat on the Labour benches. In 1992, he had been offered a peerage by Neil Kinnock, then leader of the Labour Party, but declined it as he felt unable to commit himself to the time necessary "to do what was required of him in the Upper Chamber, as he always put film-making first".[62]

On 13 July 2006, Attenborough, along with his brother David, were awarded the titles of Distinguished Honorary Fellows of the University of Leicester "in recognition of a record of continuing distinguished service to the university".[63]

On 20 November 2008, Attenborough was awarded an Honorary Doctorate of Drama from the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama (RSAMD) in Glasgow.[64]

Attenborough was an Honorary Fellow of Bangor University for his contributions to film making.[65]

Pinewood Studios paid tribute to his body of work by naming a purpose-built 30,000-square-foot (2,800 m2) sound stage after him. In his absence because of illness, Lord Puttnam and Pinewood chairman Lord Grade officially unveiled the stage on 23 April 2012.[66]

The Arts for India charity committee honoured Attenborough posthumously on 19 October 2016 at an event hosted at the home of BAFTA.[67]

Filmography

edit| Year | Title | Director | Producer |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | The Angry Silence | Yes | |

| 1961 | Whistle Down the Wind | Yes | |

| 1962 | The L-Shaped Room | Yes | |

| 1964 | Séance on a Wet Afternoon | Yes | |

| 1969 | Oh! What a Lovely War | Yes | Yes |

| 1972 | Young Winston | Yes | Yes |

| 1977 | A Bridge Too Far | Yes | |

| 1978 | Magic | Yes | |

| 1982 | Gandhi | Yes | Yes |

| 1985 | A Chorus Line | Yes | |

| 1987 | Cry Freedom | Yes | Yes |

| 1992 | Chaplin | Yes | Yes |

| 1993 | Shadowlands | Yes | Yes |

| 1996 | In Love and War | Yes | Yes |

| 1999 | Grey Owl | Yes | Yes |

| 2007 | Closing the Ring | Yes | Yes |

Acting roles

edit| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | In Which We Serve | A young stoker | |

| 1943 | Schweik's New Adventures | Railway worker | |

| 1944 | The Hundred Pound Window | Tommy Draper | |

| 1945 | Journey Together | David Wilton | |

| 1946 | A Matter of Life and Death | A British pilot | |

| School for Secrets | Jack Arnold | ||

| 1947 | The Man Within | Francis Andrews | |

| Dancing with Crime | Ted Peters | ||

| 1948 | Brighton Rock | Pinkie Brown | |

| London Belongs to Me | Percy Boon | ||

| The Guinea Pig | Jack Read | ||

| 1949 | The Lost People | Jan | |

| Boys in Brown | Jackie Knowles | ||

| 1950 | Morning Departure | Stoker Snipe | |

| 1951 | Hell Is Sold Out | Pierre Bonnet | |

| The Magic Box | Jack Carter | ||

| 1952 | Gift Horse | Dripper Daniels | |

| Father's Doing Fine | Dougall | ||

| 1954 | Eight O'Clock Walk | Thomas "Tom" Leslie Manning | |

| 1955 | The Ship That Died of Shame | George Hoskins | |

| 1956 | Private's Progress | Pvt. Percival Henry Cox | |

| The Baby and the Battleship | Knocker White | ||

| 1957 | Brothers in Law | Henry Marshall | |

| The Scamp | Stephen Leigh | ||

| 1958 | Dunkirk | John Holden | |

| The Man Upstairs | Peter Watson | ||

| Sea of Sand | Brody | ||

| 1959 | Danger Within | Capt. "Bunter" Phillips | |

| I'm All Right Jack | Sidney De Vere Cox | ||

| Jet Storm | Ernest Tiller | ||

| SOS Pacific | Whitey Mullen | ||

| 1960 | The Angry Silence | Tom Curtis | |

| The League of Gentlemen | Lexy | ||

| Upgreen – And at 'Em | |||

| 1962 | Only Two Can Play | Gareth L. Probert | |

| All Night Long | Rod Hamilton | ||

| The Dock Brief aka Trial and Error | Herbert Fowle | ||

| 1963 | The Great Escape | Sqn. Ldr. Roger Bartlett "Big X" | |

| 1963 | The Pink Panther | Policeman | |

| 1964 | The Third Secret | Alfred Price-Gorham | |

| Séance on a Wet Afternoon | Billy Savage | ||

| Guns at Batasi | Regimental Sgt. Major Lauderdale | ||

| 1965 | The Flight of the Phoenix | Lew Moran | |

| 1966 | The Sand Pebbles | Frenchy Burgoyne | |

| 1967 | Doctor Dolittle | Albert Blossom | |

| 1968 | Only When I Larf | Silas | |

| The Bliss of Mrs. Blossom | Robert Blossom | ||

| 1969 | The Magic Christian | Oxford coach | |

| 1970 | The Last Grenade | Gen. Charles Whiteley | |

| Loot | Inspector Truscott | ||

| A Severed Head | Palmer Anderson | ||

| 1971 | 10 Rillington Place | John Christie | |

| 1972 | Cup Glory | Narrator | |

| 1974 | And Then There Were None | Judge Arthur Cannon | |

| 1975 | Brannigan | Cmdr. Sir Charles Swann | |

| Rosebud | Edward Sloat | ||

| Conduct Unbecoming | Maj. Lionel E. Roach | ||

| 1977 | Shatranj Ke Khilari | Lt. General Outram | Hindi movie |

| A Bridge Too Far | Lunatic wearing glasses | Uncredited | |

| 1979 | The Human Factor | Col. John Daintry | |

| 1993 | Jurassic Park | John Hammond | |

| 1994 | Miracle on 34th Street | Kris Kringle | |

| 1996 | E=mc2 | The Visitor | |

| Hamlet | English Ambassador to Denmark | ||

| 1997 | The Lost World: Jurassic Park | John Hammond | |

| 1998 | Elizabeth | Sir William Cecil | |

| 1999 | Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat | Jacob | |

| 2002 | Puckoon | Narrator | Final film role |

| 2015 | Jurassic World | John Hammond | Archive audio only |

Video games

edit| Year | Title | Voice role |

|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Chaos Island: The Lost World | John Hammond [68] |

| 1998 | Trespasser | |

| 2015 | Lego Jurassic World | Archive Audio from the films. |

Awards and nominations

edit| Year | Title | Academy Awards | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | ||

| 1969 | Oh! What a Lovely War | 10 | 6 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1972 | Young Winston | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| 1977 | A Bridge Too Far | 8 | 4 | ||||

| 1978 | Magic | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 1982 | Gandhi | 11 | 8 | 16 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 1985 | A Chorus Line | 3 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 1987 | Cry Freedom | 3 | 7 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 1992 | Chaplin | 3 | 4 | 1 | 3 | ||

| 1993 | Shadowlands | 2 | 6 | 1 | |||

| Total | 25 | 8 | 60 | 19 | 18 | 7 | |

| Year | Title | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1982 | Gandhi | Best Picture | Won |

| Best Director | Won |

| Year | Title | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | The Angry Silence | Best British Actor | Nominated |

| 1962 | The Dock Brief | Nominated | |

| 1964 | Guns at Batasi | Won | |

| Séance on a Wet Afternoon | |||

| 1969 | Oh! What a Lovely War | Best Direction | Nominated |

| 1977 | A Bridge Too Far | Nominated | |

| 1982 | Gandhi | Best Film | Won |

| Best Direction | Won | ||

| BAFTA Fellowship | Won | ||

| 1987 | Cry Freedom | Best Film | Nominated |

| Best Direction | Nominated | ||

| 1993 | Shadowlands | Best Film | Nominated |

| Best Direction | Nominated | ||

| Outstanding British Film | Won | ||

| Year | Title | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | The Sand Pebbles | Best Supporting Actor | Won |

| 1967 | Doctor Dolittle | Won | |

| 1982 | Gandhi | Best Director | Won |

| 1985 | A Chorus Line | Nominated | |

| 1987 | Cry Freedom | Nominated |

Portrayals

editIn early 1973, he was portrayed as "Dickie Attenborough" in the British Showbiz Awards sketch late in the third series of Monty Python's Flying Circus. Attenborough is portrayed by Eric Idle as effusive and simpering. A portrayal similar to that seen in Monty Python can be seen in the early series of Spitting Image, when Attenborough's caricature regularly appeared to thank others for an imaginary award.

In 1985 he was played by Chris Barrie in The Lenny Henry Show, in the final part of a serial pastiching A Passage to India and The Jewel in the Crown. In response to the villain claiming "Gandhi won't win!", he appears in a suit covered in Academy Awards and declares "We've already won!"

In 2012 Attenborough was portrayed by Simon Callow in the BBC Four biopic The Best Possible Taste, about Kenny Everett.

Harris Dickinson plays Attenborough in the 2022 comedy murder mystery See How They Run.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "The Mousetrap at 60: why is this the world's longest-running play?". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- ^ "Richard Attenborough". Encyclopædia Britannica. 9 November 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Richard Attenborough biography". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Attenborough, Baron cr 1993 (Life Peer), of Richmond upon Thames, in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames, (Richard Samuel Attenborough) (29 Aug. 1923–24 Aug. 2014)". WHO'S WHO & WHO WAS WHO. 2007. doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U5972. ISBN 978-0-19-954089-1. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ Elgott, Jessica (2 April 2009). "The children Britain took to its heart". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Entirely Up To You, Darling by Diana Hawkins & Richard Attenborough; pp. 29–30; paperback; Arrow Books; published 2009; ISBN 978-0-099-50304-0

- ^ Entirely Up To You, Darling by Diana Hawkins & Richard Attenborough; pp. 88–95; paperback; Arrow Books; published 2009; ISBN 978-0-099-50304-0

- ^ "Bob Hope Takes Lead from Bing in Popularity". The Canberra Times (ACT: 1926–1954). ACT: National Library of Australia. 31 December 1949. p. 2. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- ^ Entirely Up To You, Darling by Diana Hawkins & Richard Attenborough; page 180; paperback; Arrow Books; published 2009; ISBN 978-0-099-50304-0

- ^ "Richard Attenborough's RECORD RENDEZVOUS". Radio Times (1380): 41. 1 April 1950 – via BBC Genome.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Richard Attenborough at IMDb

- ^ Flynn, Bob (2 August 2002). "Arts: Filming Spike Milligan's Puckoon". The Guardian. London, UK.

- ^ "U Extends Contract With Attenborough As 'Freedom' Bows". Variety. 11 November 1987. pp. 4, 23.

- ^ Works nabs U.K. rights to Closing The Ring from The Hollywood Reporter

- ^ "A Bridge Too Far – Full Cast & Crew". IMDb. 1977.

- ^ "Richard Attenborough Fellowship Fund". Muscular-dystrophy.org. Archived from the original on 5 November 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ a b "Richard Attenborough. Biography". IMDb. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ "Cry Freedom (1987). Trivia". IMDb. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Robinson, David (1 September 2014). "Remembering Richard Attenborough". BFI. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "Our Vision". The University of Leicester. Attenborough Arts Centre. 8 June 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ "Attenborough Arts Centre". Disability Arts Online/. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Gurner, Richard. "Lord Attenborough steps down as Sussex University chancellor". The Argus. Brighton, UK. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Valleywood film studios faces possible sell-off". BBC News. 3 March 2011.

- ^ Daniels, Nia. William Shakespeare heads to Wales at theknowledgeonline.com, 13 July 2016.

- ^ Hattenstone, Simon (6 September 2008). "Richard Attenborough on laughter, levity and the loss of his daughter". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Ann Talbot (18 September 2009). "A New World: A Life of Thomas Paine by Trevor Griffiths". World Socialist Website. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Peter T. Chattaway (11 June 2008). "Flashback: Sir Richard Attenborough, the Grey Owl interview". Patheos. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Reformer may be captured on film". BBC News. 23 September 2003. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Dickie Attenborough gets help from Luton film makers". Bedford Today. 10 June 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "A Gift for Dickie". Directors Notes. 5 May 2008. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Index – University of Leicester". Embracearts.co.uk. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Lady Attenborough – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. 21 January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ News: Chelsea Football Club, Chelsea F.C., August 2014.

- ^ a b Born, Matt (29 December 2004). "Triple tragedy hits Attenborough family". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Attenborough family's fatal tsunami decision". BBC News. 18 December 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Obituary: Jane Attenborough". The Guardian. 8 April 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- ^ Freedland, Jonathan (3 February 2024). "'People said it did in his career': 33 pictures that defined British politicians". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Richard Attenborough endorses Labour in 2005 General Election, The Guardian, 26 April 2005.

- ^ Hurst, Greg. "Richard Attenborough's Picasso ceramics". The Times. London, UK. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ "Entirely Up to You, Darling by Richard Attenborough". www.penguin.com.au. Retrieved 19 October 2022.

- ^ Hawkins, Diana (2009). Entirely Up to You, Darling. London: Arrow. p. 336. ISBN 978-0099503040.

- ^ a b c Hall, Melanie (26 March 2013). "Film director Richard Attenborough moved to care home". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ^ Adams, Stephen (11 November 2009). "Lord Attenborough's picture sale makes £4.6m at Sotheby's". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Simon (23 January 2011). "Richard Attenborough seeks compensation after he is forced to sell Scottish estate at knock-down price". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Walker, Tim (12 May 2011). "Lord Attenborough takes a final bow". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Lord Attenborough's family rally round as Sheila Sim is hit by illness". The Daily Telegraph. 27 July 2012. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ Walker, Tim. "Lord Attenborough gives up an £11.5 million love affair", The Daily Telegraph (London), 29 October 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ "Actor Richard Attenborough dies at 90". BBC News. 24 August 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Johnston, Chris (24 August 2014). "Richard Attenborough dies aged 90". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Richard Attenborough's last request: place my ashes with my daughter and granddaughter". The Daily Telegraph. 4 October 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Richard Attenborough's ashes to be interred with daughter". The Times of India.

- ^ "No. 44326". The London Gazette (Supplement). 10 June 1967. p. 6278.

- ^ "No. 46777". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 January 1976. p. 1.

- ^ "No. 46828". The London Gazette. 17 February 1976. p. 2435.

- ^ "Padma Awards" (PDF). Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Commemorative Services: Martin Luther King Jr". Thekingcenter.org. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ^ "Richard Attenborough – face of British cinema for half a century". Financial Times. 24 August 2014.

- ^ Fellows: King's College London, King's College London. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Burke's Peerage – Preview Family Record". Burkes-peerage.net. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "No. 53397". The London Gazette. 10 August 1993. p. 13291.

- ^ Entirely Up To You, Darling by Diana Hawkins & Richard Attenborough; pp 245–50; Arrow Books; published 2009; ISBN 978-0-099-50304-0

- ^ "Honorary Degrees and Distinguished Honorary Fellowships Announced by University of Leicester". University of Leicester. 9 June 2006. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Actors honoured by arts academy". BBC News. 5 November 2008. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Lord Attenborough, Honorary Fellow, Bangor University". Bangor.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "The Richard Attenborough Stage opens for business at Pinewood Studios". pinewoodgroup.com. 23 April 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Arts for India to honour Sir Richard Attenborough posthumously". 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Jurassic Park: Chaos Island (video game 1997) - IMDB.com". IMDB.com. 18 November 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

External links

edit- Richard Attenborough at IMDb

- Richard Attenborough on Charlie Rose

- Richard Attenborough Archive on the British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA) site

- University of Sussex media release about Lord Attenborough's election as Chancellor, dated Friday, 20 March 1998

- Portraits of Richard Attenborough at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Lord Attenborough at the BFI's Screenonline

- Richard Attenborough Stills & Posters Gallery from the British Film Institute

- Richard Attenborough Centre for Disability and the Arts

- Richard Attenborough in Leicester website

- Profile at Parliament of the United Kingdom

- Contributions in Parliament at Hansard

- Contributions in Parliament at Hansard 1803–2005

- Voting record at PublicWhip.org

- Record in Parliament at TheyWorkForYou.com

- Richard Attenborough at Virtual History