Dunbar Theatre was a 1600-seat theatre and jazz club on the corner of Lombard Street and Broad Street in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[1] It opened in 1919 and was later called the Gibson Theatre and Lincoln Theatre.

History

editThe theatre was opened on December 29, 1919 by African-American bankers E. C. Brown and Andrew Stevens, Jr. with a performance from the Lafayette Theatre group from Harlem, who were raising money for the NAACP and Marcus Garvey. They performed Shuffle Along at Dunbar, before moving to Broadway where it premiered as the first all-black cast and production.[2] Brown and Stevens ran into financial difficulty and in September 1921[3] the theatre was acquired by businessman John T. Gibson, who bought it for $420,000,[4] offering a 10% share to another partner.[2][5] The club, which was renamed the Gibson Theatre, along with the Standard Theatre made Gibson the wealthiest African-American in Philadelphia in the 1920s.[6]

Despite his wealth and the club's success, Gibson was ruined by The Great Depression, and the theatre was sold to Jewish owners in December 1929,[7] who renamed it the Lincoln Theatre.[2] As early as October 1928 it was announced that Irvin C. Miller would take over the theatre, known at the time as the Gibson.[8]

It flourished as a jazz venue in the 1930s and 1940s with performances from the likes of Duke Ellington, Lena Horne and the Nicholas Brothers.[2]

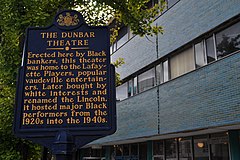

Today there is a historical marker sign at 500 South Broad Street on the southwest corner of Broad and Lombard Streets in the city remembering the theatre and its role in history as a successful venue for black performers of the 1920s to 1940s.[2]

References

edit- ^ Ted Vincent (1995). Keep Cool:The Black Activists Who Built the Age of Jazz. Pluto Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-7453-0922-4.

- ^ a b c d e "The Dunbar Theatre". Explorehistory.com. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Variety (September 1921), p.6.

- ^ "Philadelphia Pioneers in Business". The Crisis. May 1944. p. 152.

- ^ The Western Journal of Black Studies. Black Studies Program at Washington State University and Washington State University Press. 1992. p. 42.

- ^ Patrick Glennon (18 May 2018). "The Philly Venues". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Henry Louis Gates Jr; Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham (2009). Harlem Renaissance Lives from the African American National Biography. Oxford University Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-19-538795-7.

- ^ Variety (October 1928), p. 37.