This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (April 2022) |

The final battles of the European theatre of World War II continued after the definitive surrender of Nazi Germany to the Allies, signed by Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel on 8 May 1945 (VE Day) in Karlshorst, Berlin. After German leader Adolf Hitler's suicide and handing over of power to Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz on the last day of April 1945, Soviet troops conquered Berlin and accepted surrender of the Dönitz-led government. The last battles were fought on the Eastern Front which ended in the total surrender of all of Nazi Germany’s remaining armed forces such as in the Courland Pocket in western Latvia from Army Group Courland in the Baltics surrendering on 10 May 1945 and in Czechoslovakia during the Prague offensive on 11 May 1945.

Final events before the end of the war in Europe

editAllied forces begin to take large numbers of Axis prisoners: The total number of prisoners taken on the Western Front in April 1945 by the Western Allies was 1,500,000.[1] April also witnessed the capture of at least 120,000 German troops by the Western Allies in the last campaign of the war in Italy.[2] In the three to four months up to the end of April, over 800,000 German soldiers surrendered on the Eastern Front.[2] In early April, the first Allied-governed Rheinwiesenlager camps were established in western Germany to hold hundreds of thousands of captured or surrendered Axis Forces personnel. Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) reclassified all prisoners as Disarmed Enemy Forces, not POWs (prisoners of war). The legal fiction circumvented provisions under the Geneva Convention of 1929 on the treatment of former combatants.[3] By October, thousands had died in the camps from starvation, exposure and disease.[4]

Liberation of Nazi concentration camps and refugees: Allied forces began to discover the scale of the Holocaust, confirming the findings of Pilecki's 1943 Report. The advance into Germany uncovered numerous Nazi concentration camps and forced labour facilities. Up to 60,000 prisoners were at Bergen-Belsen when it was liberated on 15 April 1945, by the British 11th Armoured Division.[5] Four days later troops from the American 42nd Infantry Division found Dachau.[6] Allied troops forced the remaining SS guards to gather up the corpses and place them in mass graves.[7] Due to the prisoners' poor physical condition, thousands continued to die after liberation.[8] Captured SS guards were subsequently tried at Allied war crime tribunals where many were sentenced to death.[9] Some Nazi guards and personnel were killed outright upon the discovery of their crimes. However, up to 10,000 Nazi war criminals eventually fled Europe using ratlines.

German forces withdraw from Finland: On 25 April 1945, the last German troops withdrew from Finnish Lapland and made their way into occupied Norway. On 27 April 1945, the Raising the Flag on the Three-Country Cairn photograph was taken.[10]

Mussolini is executed: On 25 April 1945, Italian partisans liberated Milan and Turin. On 27 April 1945, as Allied forces closed in on Milan, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was captured by Italian partisans. It is disputed whether he was trying to flee from Italy to Switzerland (through the Splügen Pass), and was travelling with a German anti-aircraft battalion. On 28 April, Mussolini was executed in Giulino (a civil parish of Mezzegra); the other fascists captured with him were taken to Dongo and executed there. The bodies were then taken to Milan and hung up on the Piazzale Loreto of the city. On 29 April, Rodolfo Graziani surrendered all Fascist Italian armed forces at Caserta. This included Army Group Liguria. Graziani was the Minister of Defence for Mussolini's Italian Social Republic.

Hitler dies by suicide: On 30 April 1945, as the Battle of Nuremberg and the Battle of Hamburg ended with American and British occupation, the Battle in Berlin was still raging. With the Soviets surrounding Berlin and his escape route cut off by the Americans, German dictator Adolf Hitler, realizing that all was lost and not wishing to suffer Mussolini's fate, died by suicide in his Führerbunker along with his long-term partner Eva Braun, whom he had married less than 40 hours earlier.[11] In his will, Hitler dismissed Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, his second-in-command, and Interior minister Heinrich Himmler after each of them separately tried to seize control of the crumbling remains of Nazi Germany. Hitler appointed his successors as follows; Großadmiral Karl Dönitz as the new Reichspräsident ("President of Germany") and Joseph Goebbels as the new Reichskanzler (Chancellor of Germany). However, Goebbels died by suicide the next day, leaving Dönitz as the sole leader of Germany.

German forces in Italy surrender: On 29 April, the day before Hitler died, Oberstleutnant Schweinitz and Sturmbannführer Wenner, plenipotentiaries for Generaloberst Heinrich von Vietinghoff and SS Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff, signed a surrender document at Caserta[12] after prolonged unauthorised secret negotiations with the Western Allies, which were viewed with great suspicion by the Soviet Union as trying to reach a separate peace. In the document, the Germans agreed to a ceasefire and surrender of all the forces under the command of Vietinghoff on 2 May at 2 pm. Accordingly, after some bitter wrangling between Wolff and Albert Kesselring in the early hours of 2 May, nearly 1,000,000 men in Italy and Austria surrendered unconditionally to British Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander on 2 May at 2 pm.[13]

German forces in Berlin surrender: The Battle of Berlin ended on 2 May. On that date, General der Artillerie Helmuth Weidling, the commander of the Berlin Defense Area, unconditionally surrendered the city to General Vasily Chuikov of the Red Army.[14] On the same day the officers commanding the two armies of Army Group Vistula north of Berlin, (General Kurt von Tippelskirch, commander of the German 21st Army and General Hasso von Manteuffel, commander of Third Panzer Army), surrendered to the Western Allies.[15] 2 May is also believed to have been the day when Hitler's deputy Martin Bormann died, from the account of Artur Axmann who saw Bormann's corpse in Berlin near the Lehrter Bahnhof railway station after encountering a Soviet Red Army patrol.[16] Lehrter Bahnhof is close to where the remains of Bormann, confirmed as his by a DNA test in 1998,[17] were unearthed on 7 December 1972.

German forces in North West Germany, Denmark, and the Netherlands surrender: On 4 May 1945, the British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery took the unconditional military surrender at Lüneburg from Generaladmiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, and General Eberhard Kinzel, of all German forces "in Holland [sic], in northwest Germany including the Frisian Islands and Heligoland and all other islands, in Schleswig-Holstein, and in Denmark… includ[ing] all naval ships in these areas",[18][19] at the Timeloberg on Lüneburg Heath; an area between the cities of Hamburg, Hanover and Bremen. The number of German land, sea and air forces involved in this surrender amounted to 1,000,000 men.[20] On 5 May, Großadmiral Dönitz ordered all U-boats to cease offensive operations and return to their bases. At 16:00 on 5 May, German Oberbefehlshaber Niederlande supreme commander Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz surrendered to I Canadian Corps commander Lieutenant-General Charles Foulkes in the Dutch town of Wageningen, in the presence of Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands (acting as commander-in-chief of the Dutch Interior Forces).[21][22]

German forces in Bavaria surrender: At 14:30 on 5 May 1945, General Hermann Foertsch surrendered all forces between the Bohemian mountains and the Upper Inn river to the American General Jacob L. Devers, commander of the American 6th Army Group.

Central Europe: On 5 May 1945, the Czech resistance started the Prague uprising. The following day, the Soviets launched the Prague offensive. In Dresden, Gauleiter Martin Mutschmann let it be known that a large-scale German offensive on the Eastern Front was about to be launched. Within two days, Mutschmann abandoned the city but was captured by Soviet troops while trying to escape.[23]

Hermann Göring's surrender: On 6 May, Reichsmarshall and Hitler's second-in-command Hermann Göring surrendered to General Carl Spaatz, who was the commander of the operational United States Air Forces in Europe, along with his wife and daughter at the Germany-Austria border.

German forces in Breslau surrender: At 18:00 on 6 May, General Hermann Niehoff, the commandant of Breslau, a 'fortress' city surrounded and besieged for months, surrendered to the Soviets.[22]

Jodl and Keitel surrender all German armed forces unconditionally: Thirty minutes after the fall of "Festung Breslau" (Fortress Breslau), General Alfred Jodl arrived in Reims and, following Dönitz's instructions, offered to surrender all forces fighting the Western Allies. This was exactly the same negotiating position that von Friedeburg had initially made to Montgomery, and like Montgomery, the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, threatened to break off all negotiations unless the Germans agreed to a complete unconditional surrender to all the Allies on all fronts.[24] Eisenhower explicitly told Jodl that he would order western lines closed to German soldiers, thus forcing them to surrender to the Soviets.[24] Jodl sent a signal to Dönitz, who was in Flensburg, informing him of Eisenhower's declaration. Shortly after midnight, Dönitz, accepting the inevitable, sent a signal to Jodl authorizing the complete and total surrender of all German forces.[22][24]

Channel Islanders were informed about the German surrender after: At 10:00 on 8 May, the Channel Islanders were informed by the German authorities that the war was over. British prime minister Winston Churchill made a radio broadcast at 15:00 during which he announced: "Hostilities will end officially at one minute after midnight tonight, but in the interests of saving lives the 'Cease fire' began yesterday to be sounded all along the front, and our dear Channel Islands are also to be freed today."[25][26]

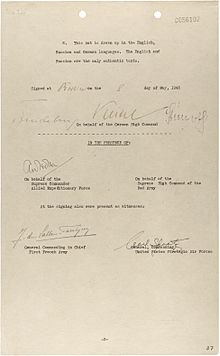

At 02:41 on the morning of 7 May, at SHAEF headquarters in Reims, France, the chief-of-staff of the German Armed Forces High Command, General Alfred Jodl, signed an unconditional surrender document for all German forces to the Allies. General Franz Böhme announced the unconditional surrender of German troops in Norway on 7 May. It included the phrase "All forces under German control to cease active operations at 23:01 hours Central European Time on May 8, 1945."[18][26] The next day, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel and other German OKW representatives travelled to Berlin, and shortly before midnight signed another document of unconditional surrender, again surrendering to all the Allied forces, this time in the presence of Marshal Georgy Zhukov and representatives of SHAEF.[27] The signing ceremony took place in a former German Army Engineering School in the Berlin district of Karlshorst; it now houses the German-Russian Museum Berlin-Karlshorst.

Aftermath of the war

editVE-Day: Following news of the German surrender, spontaneous celebrations erupted all over the world on 7 May, including in Western Europe and the United States. As the Germans officially set the end of operations for 2301 Central European Time on 8 May, that day is celebrated across Europe as V-E Day. Most of the former Soviet Union celebrates Victory Day on 9 May, as the end of operations occurred after midnight Moscow Time.

- On 8 May, Muslims in French Algeria celebrating the end of the war became the targets of violence and massacres by colonial authorities and pied-noir settler militias, which would continue until 26 June 1945.[28][29][30] While largely overlooked in metropolitan France, the impact on the Algerian Muslim population was traumatic,[31] becoming a precursor to the Algerian War nine years later.[32]

German units cease fire: Although the military commanders of most German forces obeyed the order to surrender issued by the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW)—the German Armed Forces High Command—not all commanders did so. The largest contingent was Army Group Centre under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Ferdinand Schörner, who had been promoted to Commander-in-Chief of the Army on 30 April in Hitler's last will and testament. On 8 May, Schörner deserted his command and flew to Austria; the Soviet Army sent overwhelming force against Army Group Centre in the Prague offensive, forcing many of the German units in there to capitulate by 11 May. The other units of the Army Group which did not surrender on 8 May were forced to surrender.

- On, 9 May, the Second Army, under the command of General von Saucken, on the Heiligenbeil and Danzig beachheads, on the Hel Peninsula in the Vistula delta surrendered; as did the forces on the Greek islands; and the garrisons of most of the last Atlantic pockets in France, in Dunkirk and La Rochelle (after the Allied siege).

- The Atlantic Pocket of Lorient surrendered on 10 May.

- The Atlantic Pocket of Saint-Nazaire surrendered on 11 May.

- The Battle of Slivice, the last battle in occupied Czechoslovakia, occurred on 12 May.

- On 13 May, the Red Army halted all offensives in Europe. Isolated pockets of resistance in Czechoslovakia were mopped up by this date.

- The garrison on Minquiers, one of the Channel Islands occupied by the Germans, surrendered on 23 May, one week after the garrison on Alderney, and two weeks after the garrisons on Guernsey and Jersey had surrendered (on 9 May) and those on Sark (on 10 May).

- A military engagement took place in Yugoslavia (today's Slovenia), on 14 and 15 May, known as the Battle of Poljana.

- The fighting during the Georgian uprising on Texel in the Netherlands lasted until 20 May.

- The last battle in Europe, the Battle of Odžak between the Yugoslav Army and the Croatian Armed Forces, concluded on 25 May. The remaining Croatian soldiers escaped to the forest.

- German forces on Ameland and Schiermonnikoog, 2 Dutch islands in the Wadden Sea, surrendered on 3 and 11 June respectively. The latter was the last German force in the Netherlands to surrender.[33][34]

- A small group of German soldiers, deployed on Svalbard in Operation Haudegen to establish and man a weather station there, lost radio contact in May 1945; they surrendered to some Norwegian seal hunters on 6 September, four days after Japan formally surrendered.

Debellation: At the time the Allied powers assumed that a debellation had occurred (the end of a war caused by the complete destruction of a hostile state), and their actions during the immediate post war period were based on that legal premise (however, the German government's legal position during and following the reunification of Germany is that the state remained in existence although moribund in the immediate post war period).[35][36][a]

Dönitz government ordered dissolved by Eisenhower: Karl Dönitz continued to act as if he were the German head of state, but his Flensburg Government (so called because it was based at Flensburg in northern Germany and controlled only a small area around the town), was not recognized by the Allies. On 12 May an Allied liaison team arrived in Flensburg and took quarters aboard the passenger ship Patria. The liaison officers and the Supreme Allied Headquarters soon realized that they had no need to act through the Flensburg government and that its members should be arrested. On 23 May, acting on SHAEF's orders and with the approval of the Soviets, American Major General Rooks summoned Dönitz aboard the Patria and communicated to him that he and all the members of his Government were under arrest and that their government was dissolved. The Allies had a problem because they realized that although the German armed forces had surrendered unconditionally, SHAEF had failed to use the document created by the "European Advisory Commission" (EAC) and so there had been no formal surrender by the civilian German government. This was considered a very important issue, because just as the civilian, but not military, surrender in 1918 had been used by Hitler to create the "stab in the back" argument, the Allies did not want to give any future hostile German regime a legal argument to resurrect an old quarrel.

On 20 September 1945, the Allied Control Council passed its Control Council Law No. 1 - Repealing of Nazi Laws, which repealed numerous pieces of legislation enacted by the national-socialist regime, putting a de jure end to the Government of Nazi Germany. Incidentally, this law should have theoretically reestablished the Weimar Constitution; however, this constitution stayed irrelevant on the grounds of the powers of the Allied Control Council acting as occupying forces. On 10 October 1945, Control Council Law No. 2 was also passed, formally abolishing all national socialist organisations.[37]

The Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany and the Assumption of Supreme Authority by Allied Powers was signed by the four Allies on 5 June. It included the following:

The Governments of the United States of America, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the United Kingdom and the Provisional Government of the French Republic, hereby assume supreme authority with respect to Germany, including all the powers possessed by the German Government, the High Command and any state, municipal, or local government or authority. The assumption, for the purposes stated above, of the said authority and powers does not effect[38] the annexation of Germany [i.e., the document does not authorize the Allies to annex Germany].[39]

The Potsdam Agreement was signed on 1 August 1945. In connection with this, the leaders of the United States, Britain and the Soviet Union planned the new postwar German government, resettled war territory boundaries, de facto annexed a quarter of pre-war Germany situated east of the Oder–Neisse line, and mandated and organized the expulsion of the millions of Germans who remained in the annexed territories and elsewhere in the east. They also ordered German demilitarization, denazification, industrial disarmament and settlements of war reparations. But, as France (at American insistence) had not been invited to the Potsdam Conference, so the French representatives on the Allied Control Council subsequently refused to recognise any obligation to implement the Potsdam Agreement; with the consequence that much of the programme envisaged at Potsdam, for the establishment of a German government and state adequate for accepting a peace settlement, remained a dead letter.

Operation Keelhaul began the Allies' forced repatriation of displaced persons, families, anti-communists, White Russians, former Soviet Armed Forces POWs, foreign slave workers, soldier volunteers and Cossacks, and Nazi collaborators to the Soviet Union. Between 14 August 1946 and 9 May 1947, up to five million people were forcibly handed over to the Soviets.[40] On return, most deportees faced imprisonment or execution; on some occasions the NKVD began killing people before Allied troops had departed from the rendezvous points.[41]

The Allied Control Council was created to effect the Allies' assumed supreme authority over Germany, specifically to implement their assumed joint authority over Germany. On 30 August, the Control Council constituted itself and issued its first proclamation, which informed the German people of the council's existence and asserted that the commands and directives issued by the Commanders-in-Chief in their respective zones were not affected by the establishment of the council.

Cessation of formal hostilities and peace treaties

editCessation of hostilities between the United States and Germany was proclaimed on 13 December 1946 by US President Truman.[42]

The Paris Peace Conference ended on 10 February 1947 with the signing of peace treaties by the wartime Allies with the former European Axis powers (Italy, Romania, Hungary and Bulgaria) and their co-belligerent ally Finland.

The Federal Republic of Germany, which had been founded on 23 May 1949 (when its Basic Law was promulgated), had its first government formed on 20 September 1949 while the German Democratic Republic was formed on 7 October.

End of state of war with Germany was declared by many former Western Allies from 1950.[43] In the Petersberg Agreement of 22 November 1949, it was noted that the West German government wanted an end to the state of war, but the request could not be granted. The US state of war with Germany was being maintained for legal reasons, and though it was softened somewhat it was not suspended since "the US wants to retain a legal basis for keeping a US force in Western Germany".[44] At a meeting for the foreign ministers of France, the UK, and the US in New York from 12 September – 19 December 1950, it was stated that among other measures to strengthen West Germany's position in the Cold War that the western allies would "end by legislation the state of war with Germany".[45] In 1951, many former Western Allies did end their state of war with Germany: Australia (9 July), Canada, Italy, New Zealand, the Netherlands (26 July), South Africa, the United Kingdom (9 July), and the United States (19 October).[46][47][48][49][50][51] The state of war between Germany and the Soviet Union was ended in early 1955.[52]

"The full authority of a sovereign state" was granted to the Federal Republic of Germany on 5 May 1955 under the terms of the Bonn–Paris conventions. The treaty ended the military occupation of West German territory, but the three occupying powers retained some special rights, e.g. vis-à-vis West Berlin.

The Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany was signed following the 1990 German reunification, whereby the Four Powers renounced all rights they formerly held in the newly single country, including Berlin. The treaty came into force on 15 March 1991. Under the terms of the Treaty, the Allies were allowed to keep troops in Berlin until the end of 1994 (articles 4 and 5). In accordance with the Treaty, occupying troops were withdrawn by that deadline.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Although the Allied powers considered this a debellatio (The human rights dimensions of population, UNHCR web site, p. 2 § 138) other authorities have argued that the vestiges of the German state continued to exist even though the Allied Control Council governed the territory; and that eventually a fully sovereign German government resumed over a state that never ceased to exist (Junker, Detlef (2004), Junker, Detlef; Gassert, Philipp; Mausbach, Wilfried; et al. (eds.), The United States and Germany in the Era of the Cold War, 1945–1990: A Handbook, vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, co-published with German Historical Institute, Washington D.C., p. 104, ISBN 0-521-79112-X.)

References

editCitations

edit- ^ The Daily Telegraph Story of the War, (January 1st to October 7th 1945) page 153

- ^ a b The Times, 1 May 1945, page 4

- ^ Biddiscombe, Alexander Perry, (1998). Werwolf!: The History of the National Socialist Guerrilla Movement, 1944-1946. University of Toronto Press. p. 253. ISBN 0-8020-0862-3

- ^ Davidson, Eugene (1999). The Death and Life of Germany. University of Missouri Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 0-8262-1249-2.

- ^ "The 11th Armoured Division (Great Britain)", United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- ^ "Station 11: Crematorium – Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site". Kz-gedenkstaette-dachau.de. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ^ Wiesel, Elie (2002). After the Darkness: Reflections on the Holocaust. New York, NY: Schocken Books. p. 41.

- ^ Knoch, Habbo (2010). Bergen-Belsen: Wehrmacht POW Camp 1940–1945, Concentration Camp 1943–1945, Displaced Persons Camp 1945–1950. Catalogue of the permanent exhibition. Wallstein. p. 103. ISBN 978-3-8353-0794-0.

- ^ Greene, Joshua (2003). Justice At Dachau: The Trials Of An American Prosecutor. New York: Broadway. p. 400. ISBN 0-7679-0879-1.

- ^ Kulju, Mika (2017). "Chpt. 4". Käsivarren sota – lasten ristiretki 1944–1945 [The war in the Arm – children's crusade 1944–1945] (e-book) (in Finnish). Gummerus. ISBN 978-951-24-0770-5.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. 342.

- ^ Ernest F. Fisher Jr: United States Army in WWII, The Mediterranean - Cassino to the Alps. Page 524.

- ^ Daily Telegraph Story of the War fifth volume page 153

- ^ Dollinger, Hans. The Decline and the Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 67-27047. p. 239

- ^ Ziemke 1969, p. 128.

- ^ Beevor 2002, p. [page needed].

- ^ Karacs, Imre (4 May 1998). "DNA test closes book on mystery of Martin Bormann". Independent. London. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- ^ a b "The German Surrender Documents – WWII". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2005.

- ^ "Monty Speech & German Surrender 1945". British Pathé. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ The Times, 5 May 1945, page 4

- ^ "World War II Timeline:western Europe: 1945". Archived from the original on 22 September 2006.

- ^ a b c Ron Goldstein Field Marshal Keitel's surrender BBC additional comment by Peter – WW2 Site Helper

- ^ [Page 228, "The Decline and Fall of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan", Hans Dollinger, Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 67-27047]

- ^ a b c Ziemke 1969, p. 130.

- ^ "The Churchill Centre: The End of the War in Europe". Archived from the original on 19 June 2006.

- ^ a b During the summers of World War II, Britain was on British Double Summer Time which meant that the country was ahead of CET time by one hour. This means that the surrender time in the UK was "effective from 0001 hours on May 9".RAF Site Diary 7/8 May Archived 18 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ziemke 1990, p. 258 last paragraph.

- ^ Morgan, Ted (31 January 2006). My Battle of Algiers. HarperCollins. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-06-085224-5.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (1977). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954–1962. New York: The Viking Press. p. 26.

- ^ Peyroulou, Jean-Pierre (2009). "6. La mise en place d'un ordre subversif, le 9 mai 1945". Guelma, 1945 : une subversion française dans l'Algérie coloniale. Paris: Éditions La Découverte. ISBN 9782707154644. OCLC 436981240.

- ^ Porch, Douglas (1991). The French Foreign Legion. Macmillan. p. 569. ISBN 978-0-333-58500-9.

- ^ Edgar O'Ballance, pages 39 and 195 "The Algerian Insurrection 1954–62", Faber and Faber London 1867

- ^ "Bevrijding – Ameland tijdens WO II". 16 September 2016. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "De bevrijding van Schier kwam pas weken later". www.omropfryslan.nl (in Dutch). 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ United Nations War Crimes Commission (1997), Law reports of trials of war criminals: United Nations War Crimes Commission, Wm. S. Hein, p. 13, ISBN 1-57588-403-8

- ^ Yearbook of the International Law Commission (PDF). Volume II (Part Two). 1995. p. 54. ISBN 92-1-133483-7. ISSN 0082-8289. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013.

- ^ Control Council. "Law No. 1 – Repealing of Nazi Laws / Law No. 2 – Providing for the Termination and Liquidation of the Nazi Organizations" (PDF).

- ^ Spelling as in the original: effect, not affect.

- ^ Documents on Germany: 1944-1959. Washington, D. C.: United States Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations. 1959. p. 13. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Nikolai Tolstoy (1977). The Secret Betrayal. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 360. ISBN 0-684-15635-0.

- ^ Murray-Brown, Jeremy (October 1992). "A footnote to Yalta". Boston University.

- ^ Werner v. United States (188 F.2d 266) Archived 14 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, United States Court of Appeals Ninth Circuit, 4 April 1951. Website of Public.Resource.Org Archived 28 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Although Belgium ended it on June 15, 1949

- ^ "A Step Forward". Time. 28 November 1949.

- ^ Staff. Full text of "Britannica Book Of The Year 1951" Open-Access Text Archive. Retrieved 11 August 2008

- ^ "War's End". Time. 16 July 1951.

- ^ Elihu Lauterpacht, C. J. Greenwood. International Law Reports. Volume 52, Cambridge University Press, 1979 ISBN 0-521-46397-1. p. 505

- ^ "Second World War (WWII)". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- ^ 1951 in History BrainyMedia.com. Retrieved 11 August 2008

- ^ H. Lauterpacht (editor), International law reports Volume 23. Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-949009-37-7. p. 773

- ^ US Code—Title 50 Appendix—War and National Defense Archived 6 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Government Printing Office Archived 29 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Spreading Hesitation". Time. 7 February 1955.

Sources

edit- Beevor, Antony (2002), Berlin: The Downfall 1945, Viking-Penguin Books

- Plenipotentiaries (5 June 1945), "Declaration Regarding the Defeat of Germany and the Assumption of Supreme Authority with respect to Germany by the United Kingdom, the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and the provisional government of the French Republic (facsimile)" (PDF), Germany No. i (1945): Unconditional Surrender of Germany Declaration and other Documents issued by the Governments of the United Kingdom, the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and the Provisional Government of the French Republic, pp. 1–6 (3–7 PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2013, retrieved 24 December 2013

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1969), Battle for Berlin: End of the Third Reich, London: Macdomald & Co, p. 128

- Ziemke, Earl F. (1990), "Chapter XV: The Victory Sealed: Surrender at Reims", The U.S. Army in the occupation of Germany 1944–1946, Center of Military History, United States Army, Washington, D. C., Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 75-619027

Further reading

edit- Deutsche Welle special coverage of the end of World War II—features a global perspective.

- On this Day 7 May 1945: Germany signs unconditional surrender

- Account of German surrender, BBC

- Charles Kiley (Stars and Stripes Staff Writer).Details of the Surrender Negotiations This Is How Germany Gave Up

- London '45 Victory Parade, photos and the exclusion of the Polish ally

- Multimedia map of the war (1024x768 & Macromedia Flash Plugin 7.x)

External links

edit- The short film A Defeated People (1946) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Civil Affairs In Germany (1945) is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive